David Hammons’ homage to Gordon Matta-Clark

The ghost of a Gordon Matta Clark post-industrial intervention is welcomed back to the Hudson River with a new sculpture outside the Whitney Museum.

fig.1

For the most part, Gordon Matta-Clark’s artwork is experienced through the distancing gaze of photography, film, or drawing. His most celebrated works, involving the incision and excision of architectures to create new openings, slits, and sightlines. The resulting forms were a kind of sculptural precarity, with buildings that verged on the edge of structural assuredness and the feeling the whole thing may collapse at any moment.

fig.ii

In 1965 he took his surgical-sculpting onto a warehouse on New York’s Pier 52. For Day’s End Matta-Clark sliced into the walls, floor, and ceiling of the dark, empty warehouse – which had found new function for gay sado-masochists, exploration site for proto urban explorers, and as a space of shadows for prostitution. Over July and August, the artist based himself in the warehouse unbeknownst to authorities:gfdgfd

“My ‘studio retreat’ consisted of appropriating a nearly perfecttly [sic] intact turn-of-the-century warf [sic] building of a steel truss construction having virtually basilical light and proportions while being a heavy industrial hangar. Once [finished with] the job of securing the space from other intruders, mainly s. and m. cruisers, I with a couple of helpers spent the next two months working out, - that is cutting and working out sections of dock 10-18 inches thick, roof, walls and heavy steel trusswork.”

(Matta-Clark, letter to Wolfgang Becker, 8 September 1975, from Gordon Matta-Clark Archives at the Canada Centre of Architecture, quoted in Thomas Crow’s essay “Legend and Myth”, in Gordon Matta-Clark, Diserens, Corinne (ed.) 2006, London & New York: Phaidon

In a statement to the police explaining his artistic

trespass and intervention, Matta-Clark spoke of his “personal feelings of bass mismanagement of the dying harbor and its ghost like terminals”. Now, over four

decades later, its spectre still haunts - the trace outline of Matta-Clark’s warehouse is visible in a new sculptural work marking the site and form of the

industrial shed.

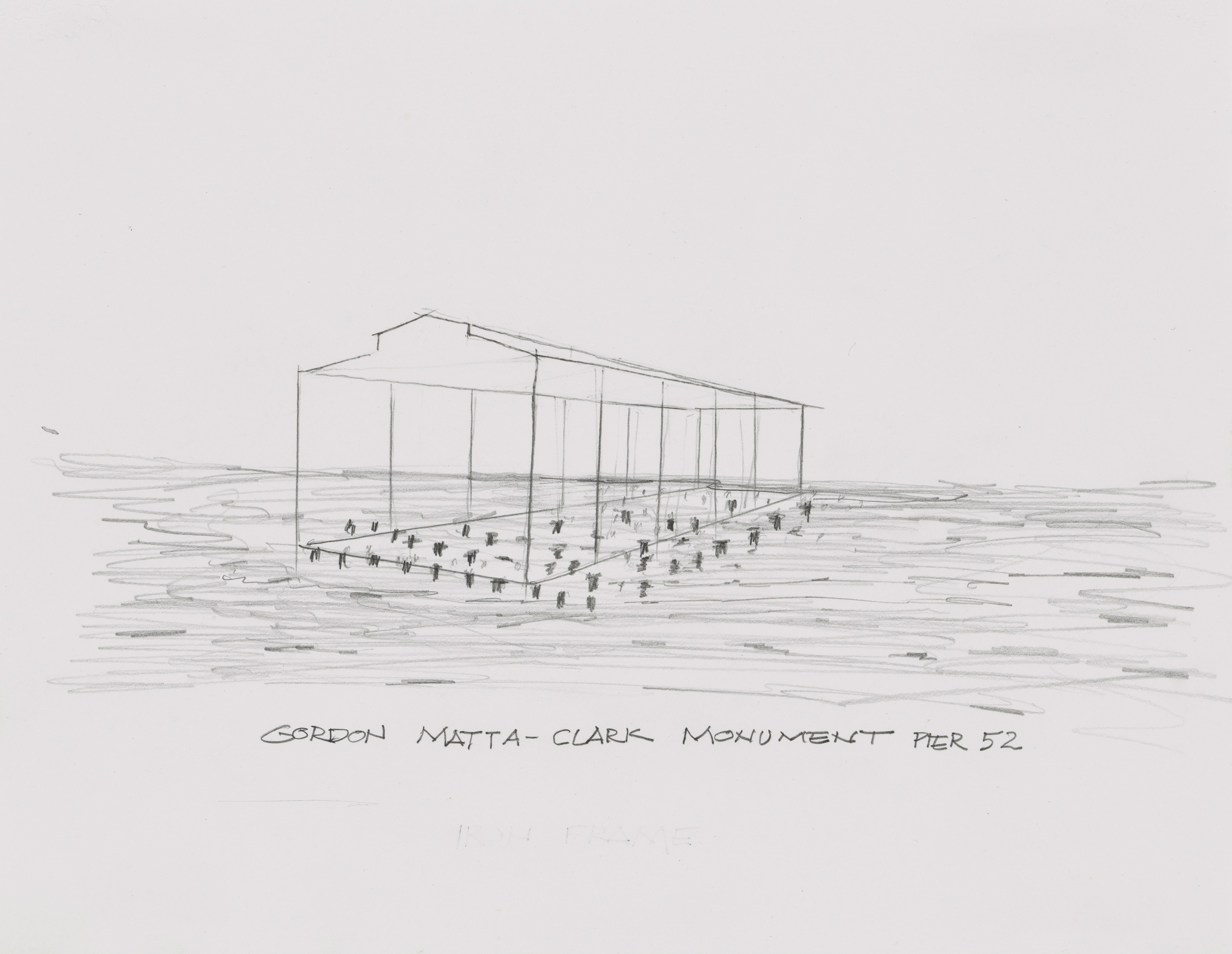

David Hemmons’ work Day’s End – the very name also bringing Matta-Clark’s project into the modern day – was created in partnership with the Whitney Museum of American Art, who worked with Guy Nordenson and Associates structural engineers to turn his 2014 sketch into a 107m by 20m sculpture, reaching 16m up from the Hudson waters it’s sited in.

![]()

![]()

David Hemmons’ work Day’s End – the very name also bringing Matta-Clark’s project into the modern day – was created in partnership with the Whitney Museum of American Art, who worked with Guy Nordenson and Associates structural engineers to turn his 2014 sketch into a 107m by 20m sculpture, reaching 16m up from the Hudson waters it’s sited in.

fig.iii

Drawing connection to the atmospheric play of light within

Matta-Clark’s work, Adam D. Weinberg, the Alice Brown Director of the Whitney,

said: "David Hammons’s Day’s End is situated on public land; it is not

owned by the Whitney; rather, it is owned by everyone and by no one, open and

free to all. Day’s End appears evanescent and ethereal, changing with the light

of day and atmospheric conditions.”

The context has changed since the 1970s. While the sculpture may evoke the memory of the dirty and transgressive history of the site—docks, gay cruising, post-industrial decay—the west side of the Meatpacking District is now home to Thomas Heatherwick’s Little Island and the High Line, as well as the Whitney Museum and some of the highest value real estate in the city. The void present within the outline form may speak not only to the absent architectural object, but also to the gentrified and radically transformed cultural and social landscape of the local area.

The context has changed since the 1970s. While the sculpture may evoke the memory of the dirty and transgressive history of the site—docks, gay cruising, post-industrial decay—the west side of the Meatpacking District is now home to Thomas Heatherwick’s Little Island and the High Line, as well as the Whitney Museum and some of the highest value real estate in the city. The void present within the outline form may speak not only to the absent architectural object, but also to the gentrified and radically transformed cultural and social landscape of the local area.

fig.iiv

further information

www.whitney.org/exhibitions/david-hammons-days-end

images

fig.i David Hammons, Day’s

End, 2014 - 2021. Stainless steel and precast concrete, overall: 52 ft

high, 325 ft long, 65 ft wide. © David Hammons. Photograph by Timothy Schenck

fig.ii Gordon Matta-Clark, (1943-1978). Day’s

End (Pier 52) (Exterior with Ice), 1975. Color photograph, 1029 x 794 mm.© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, Artists Rights

Society (ARS), N.Y.

fig.iii

David Hammons, Day’s

End, 2014. Graphite on paper, 8 ½ x 11 in (21.59 x 27.94 cm). Gift of the

artist to the Whitney Museum.

fig.iv

David Hammons, Day’s

End, 2014. - 2021. Stainless steel and precast concrete, overall: 52 ft

high, 325 ft long, 65 ft wide. © David Hammons. Photograph by Timothy Schenck.

publication date

11 January 2022

tags

Artwork, David Hammons, Gordon Matta-Clark, New York, Sculpture, Whitney

fig.ii Gordon Matta-Clark, (1943-1978). Day’s End (Pier 52) (Exterior with Ice), 1975. Color photograph, 1029 x 794 mm.© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y.

fig.iii David Hammons, Day’s End, 2014. Graphite on paper, 8 ½ x 11 in (21.59 x 27.94 cm). Gift of the artist to the Whitney Museum.

fig.iv David Hammons, Day’s End, 2014. - 2021. Stainless steel and precast concrete, overall: 52 ft high, 325 ft long, 65 ft wide. © David Hammons. Photograph by Timothy Schenck.

publication date

11 January 2022

tags

Artwork, David Hammons, Gordon Matta-Clark, New York, Sculpture, Whitney