Coimbra Biennial: contemporary art across Portugal’s historic capital

Coimbra, the historic capital of Portugal, equidistant between Lisbon & Porto, is UNESCO recognised for its exquisite Romanesque & Baroque architecture. It is also home to the ANOZERO biennial of contemporary art, with 2024’s edition recently opening. Will Jennings explored the city, its architecture & interjections of art for recessed.space.

Nearly equidistant between the tourist magnets of Lisbon and

Porto is the historic capital of Portugal, Coimbra. A UNESCO recognised World

Heritage site, it is home to one of the oldest universities in Europe, founded

in 1290, and as a centre of politics and learning the city held huge importance

in relation not only to Portugal itself, but also formerly colonised

territories in South America and Africa.

It is also home to ANOZERO, a contemporary art biennial that has been running since 2013, raises awareness of and creatively reflects upon the history, architecture, and character of the place. Its 2024 edition recently opened with the overarching title The Phantom of Liberty, and for an art and architecture lover it offers a fascinating route to discovering one of the oldest cities you may not yet know much about.

It is also home to ANOZERO, a contemporary art biennial that has been running since 2013, raises awareness of and creatively reflects upon the history, architecture, and character of the place. Its 2024 edition recently opened with the overarching title The Phantom of Liberty, and for an art and architecture lover it offers a fascinating route to discovering one of the oldest cities you may not yet know much about.

ABOUT COIMBRA

The theme The Phantom of Liberty is both a provocation and invitation to look back. It might suggest that the notion of liberty is itself an untouchable phantom, or maybe that liberty is itself a ghosty memory of an ancient idea long dead. But the curators, Ángel Calvo Ulloa and Marta Mestre, also hope to invoke something of the surreal – the title is reference to Luís Buñuel’s 1974 film of the same name. It is, after all, a century since André Breton's Manifesto of Surrealism, though another anniversary hangs in the air – five decades since Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, a pivotal moment on the nation’s path to democracy and end of colonisation.

A mix of new commissions and existing work from 38 artists can be discovered across the city, though the main presentation is centred in the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Nova, an enormous 17th century building on the city’s left bank, offering panoramic views across the historic city and with its own interesting political history – in the 19th century, following the extinction of religious orders, it became a barracks for Portugal’s military. As host venue of the biennial, the site offers layers of stories, architectural details, and traces from which work can either poetically reflect or, in some cases, directly be made to respond to.

The theme The Phantom of Liberty is both a provocation and invitation to look back. It might suggest that the notion of liberty is itself an untouchable phantom, or maybe that liberty is itself a ghosty memory of an ancient idea long dead. But the curators, Ángel Calvo Ulloa and Marta Mestre, also hope to invoke something of the surreal – the title is reference to Luís Buñuel’s 1974 film of the same name. It is, after all, a century since André Breton's Manifesto of Surrealism, though another anniversary hangs in the air – five decades since Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, a pivotal moment on the nation’s path to democracy and end of colonisation.

A mix of new commissions and existing work from 38 artists can be discovered across the city, though the main presentation is centred in the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Nova, an enormous 17th century building on the city’s left bank, offering panoramic views across the historic city and with its own interesting political history – in the 19th century, following the extinction of religious orders, it became a barracks for Portugal’s military. As host venue of the biennial, the site offers layers of stories, architectural details, and traces from which work can either poetically reflect or, in some cases, directly be made to respond to.

THE MONASTERY OF SANTA CLARA-A-NOVA

After clambering a serpentine and steep cobbled hill, the monastery is entered through a wonderfully baroque doorway. It’s transom window suitably distorts the senses in preparation of the creative explorations within. There are a mix of vast and small spaces, buried in the shadows of ground level and installations which erupt in the turrets after winding up staircases. While a large show, the biennial only uses a fraction of the rooms, and half the fun is exploring and discovering.

Some works, however, are easier to find than others. Portuguese artist Susanne Themlitz’s work fills a vaulted hall, an ad hoc wooden scaffolding as a landscape of historic and new works, presenting as staging posts of uncanny, creepy, and curious discovery. Hovering between a dream and frightening occult ritual, the structure invites investigation and in doing so dislocating connections to distant times and places come to the fore.

Sandra Poulson has been popping up increasingly at global art events – she’s in the main show of year’s Venice Biennale and recently presented a dust-infused recreation of an Angolan street market at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial. Here she builds part of an Angolan “unfinished house” – an unplastered wall which represents a minimum of boundary and associated economic fragility, using the simplest of architectural gestures to speak to colonial’s historic reduction of place. The wall interrupts a room, breaking passage for the visitor, forced either side and then invited to look through the two window openings, each protected by ornamental ironwork, a defensive boundary.

After clambering a serpentine and steep cobbled hill, the monastery is entered through a wonderfully baroque doorway. It’s transom window suitably distorts the senses in preparation of the creative explorations within. There are a mix of vast and small spaces, buried in the shadows of ground level and installations which erupt in the turrets after winding up staircases. While a large show, the biennial only uses a fraction of the rooms, and half the fun is exploring and discovering.

Some works, however, are easier to find than others. Portuguese artist Susanne Themlitz’s work fills a vaulted hall, an ad hoc wooden scaffolding as a landscape of historic and new works, presenting as staging posts of uncanny, creepy, and curious discovery. Hovering between a dream and frightening occult ritual, the structure invites investigation and in doing so dislocating connections to distant times and places come to the fore.

Sandra Poulson has been popping up increasingly at global art events – she’s in the main show of year’s Venice Biennale and recently presented a dust-infused recreation of an Angolan street market at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial. Here she builds part of an Angolan “unfinished house” – an unplastered wall which represents a minimum of boundary and associated economic fragility, using the simplest of architectural gestures to speak to colonial’s historic reduction of place. The wall interrupts a room, breaking passage for the visitor, forced either side and then invited to look through the two window openings, each protected by ornamental ironwork, a defensive boundary.

WORKS FROM THE BIENNIAL

Two of the most compelling works in the monastery are found deepest within it’s labyrinthine interior. Works by Adam Pendleton and Filipe Feijão are each found at the top of towers, only reached after clambering up endless twisting stairs. Each also presents a shock upon arrival.

French artist Feijão has created Estrutura (2019-24), an uncanny continuation of the staircase journey with a huge plaster sculpture of a spiral staircase going absolutely nowhere. The idea of extra steps reaching to the heavens at the highest point of such a religious architecture is poetic, while with the anniversary of the revolution and site’s military past in mind, there are also questions about a relentless drive for power, progress, and pomp. Craned in piece-by-piece through a window, there is also a sensation of awe upon discovery, but the scale of the work is tempered by a pleasurable littering of models, sketches, objects, and creative detritus around room, speaking to the idea of creation and process within what could be construed as an artist’s garret.

In the monastery’s other tower, there is also a surprise upon encountering Pendleton’s Toy Soldier (Notes on Robert. E. Lee, Richmond, Virginia/Strobe) (2021-22). The room is dark with a large screen hanging diagonally across the space. Pendleton’s film, a punchy, strobe-laden black and white study of a statue of Robert Lee – a Confederate general in the American Civial War – that was the target of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, then a year later removed to storage.

Pendleton’s film holds no prisoners. Relentless and fast, the artist’s montage and collage – what he calls Black Da da – breaks a simple portrait of the monument, while the soundtrack by musician Hahn Rowe includes excerpts of poet Amiri Baraka reciting their poem Dope, an urgent and punk, visceral response to racial inequality, capitalism, societal pain, and American history.

Two of the most compelling works in the monastery are found deepest within it’s labyrinthine interior. Works by Adam Pendleton and Filipe Feijão are each found at the top of towers, only reached after clambering up endless twisting stairs. Each also presents a shock upon arrival.

French artist Feijão has created Estrutura (2019-24), an uncanny continuation of the staircase journey with a huge plaster sculpture of a spiral staircase going absolutely nowhere. The idea of extra steps reaching to the heavens at the highest point of such a religious architecture is poetic, while with the anniversary of the revolution and site’s military past in mind, there are also questions about a relentless drive for power, progress, and pomp. Craned in piece-by-piece through a window, there is also a sensation of awe upon discovery, but the scale of the work is tempered by a pleasurable littering of models, sketches, objects, and creative detritus around room, speaking to the idea of creation and process within what could be construed as an artist’s garret.

In the monastery’s other tower, there is also a surprise upon encountering Pendleton’s Toy Soldier (Notes on Robert. E. Lee, Richmond, Virginia/Strobe) (2021-22). The room is dark with a large screen hanging diagonally across the space. Pendleton’s film, a punchy, strobe-laden black and white study of a statue of Robert Lee – a Confederate general in the American Civial War – that was the target of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, then a year later removed to storage.

Pendleton’s film holds no prisoners. Relentless and fast, the artist’s montage and collage – what he calls Black Da da – breaks a simple portrait of the monument, while the soundtrack by musician Hahn Rowe includes excerpts of poet Amiri Baraka reciting their poem Dope, an urgent and punk, visceral response to racial inequality, capitalism, societal pain, and American history.

ART TO DISCOVER THROUGHOUT THE MONASTERY

But it’s not just the building’s extremities that hold strong works. Spaces up and down and across the complex offer moments of intrigue. Diego Biachi’s video LaCura (2020) is a psychosexual study of artist and artistic obsession. While works from the collection of the Palais de Glace were taken into storage while the museum was refurbished, Bianchi created a sensual performative essay in which static sculptural objects receive his body in an act between care and love, but also verging on obsessiveness and creepiness in the manner of a stalker in a thriller drama – with haunting soundtrack to match.

There is also a sense of obsessiveness in Angolan artist Yonamine’s room-filling work, Sem Titulo (2024). It started following a visit to the University of Coimbra’s storage where he discovered historic Angolan objects, his installation presenting as an unpacked archive of objects, text, sculpture, and strangeness. It is a study of self, nationalistic history, and the Coimbra context as a compelling gesamtkunstwerk of colonial extraction, political ideology, and personal journey.

Patricia Gómez and María Jesús González work together, and in Coimbra co-present Seguir siendo. Santa Clara-a-Nova, 1677-2024 (2024), a haunting re-representation of the monastery’s inner-surfaces. Using a process they call wallpapering, the artists literally transfer the layers of paint, marks, and covering onto a 1:1 scale canvas, then hung within the space it has extracted evidence from. Over a series of rooms, these wallpaperings transfigure and reflect the spaces they are displayed within, and bring to the surface the religious, political, and artistic histories of the place into presence.

But it’s not just the building’s extremities that hold strong works. Spaces up and down and across the complex offer moments of intrigue. Diego Biachi’s video LaCura (2020) is a psychosexual study of artist and artistic obsession. While works from the collection of the Palais de Glace were taken into storage while the museum was refurbished, Bianchi created a sensual performative essay in which static sculptural objects receive his body in an act between care and love, but also verging on obsessiveness and creepiness in the manner of a stalker in a thriller drama – with haunting soundtrack to match.

There is also a sense of obsessiveness in Angolan artist Yonamine’s room-filling work, Sem Titulo (2024). It started following a visit to the University of Coimbra’s storage where he discovered historic Angolan objects, his installation presenting as an unpacked archive of objects, text, sculpture, and strangeness. It is a study of self, nationalistic history, and the Coimbra context as a compelling gesamtkunstwerk of colonial extraction, political ideology, and personal journey.

Patricia Gómez and María Jesús González work together, and in Coimbra co-present Seguir siendo. Santa Clara-a-Nova, 1677-2024 (2024), a haunting re-representation of the monastery’s inner-surfaces. Using a process they call wallpapering, the artists literally transfer the layers of paint, marks, and covering onto a 1:1 scale canvas, then hung within the space it has extracted evidence from. Over a series of rooms, these wallpaperings transfigure and reflect the spaces they are displayed within, and bring to the surface the religious, political, and artistic histories of the place into presence.

THE BIENNIAL CONTINUES ACROSS THE COMPLEX

Works can also be found in outbuildings across the monastery complex. In a garage building, Mauro Cerqueira’s von Hand zu Hand (2021) repurposes items found in second-hand stores. A large hand sculptures seem to hold sheets of fractured glass in a precarious position, another is on the verge of spilling a water-filled object, another is suspended nervously above more glass that would shatter if it was to fall. There is a tension present, perhaps speaking to the precarity of democracy over five decades since Portugal’s revolution, aware of the delicate shifts in global politics that can have huge impact.

A tiled outbuilding and an adjoining cavern-like primordial dark space are where João Marçal has positioned two juxtaposing pieces. In the crisp-clean whiteness of what was once a washroom, a stark yellow structure holds patterns from upholstery of his life – buses, childhood wallpaper, packaging – everyday design that disappears into holes of memory. This new commission, Angel’s Share (2024), celebrates what would dissipate into time – the work’s title referencing an idiom related to liquid that evaporates during whisky distillation. The adjoining, cave-like space offers a sinister sound piece for one person at a time. Looking down into a watery hole, the dripping and echoes of the space mingle with ghostly memories of the artist’s journey here into a very othering experience.

Berio Molina’s work projects away from the monastery and towards the city of Coimbra. Despite being 50kms from the coast, at random times over the day Molina’s two nautical horns loudly project across the Mondego River and can be clearly heard in the town’s main squares and streets. It causes not only a geographic connection, but one across time and ideas – the horns were bought from an Indian ship graveyard, their loud drone perhaps also a signal of ecological and consumerist collapse from the Global South to the Global North.

Works can also be found in outbuildings across the monastery complex. In a garage building, Mauro Cerqueira’s von Hand zu Hand (2021) repurposes items found in second-hand stores. A large hand sculptures seem to hold sheets of fractured glass in a precarious position, another is on the verge of spilling a water-filled object, another is suspended nervously above more glass that would shatter if it was to fall. There is a tension present, perhaps speaking to the precarity of democracy over five decades since Portugal’s revolution, aware of the delicate shifts in global politics that can have huge impact.

A tiled outbuilding and an adjoining cavern-like primordial dark space are where João Marçal has positioned two juxtaposing pieces. In the crisp-clean whiteness of what was once a washroom, a stark yellow structure holds patterns from upholstery of his life – buses, childhood wallpaper, packaging – everyday design that disappears into holes of memory. This new commission, Angel’s Share (2024), celebrates what would dissipate into time – the work’s title referencing an idiom related to liquid that evaporates during whisky distillation. The adjoining, cave-like space offers a sinister sound piece for one person at a time. Looking down into a watery hole, the dripping and echoes of the space mingle with ghostly memories of the artist’s journey here into a very othering experience.

Berio Molina’s work projects away from the monastery and towards the city of Coimbra. Despite being 50kms from the coast, at random times over the day Molina’s two nautical horns loudly project across the Mondego River and can be clearly heard in the town’s main squares and streets. It causes not only a geographic connection, but one across time and ideas – the horns were bought from an Indian ship graveyard, their loud drone perhaps also a signal of ecological and consumerist collapse from the Global South to the Global North.

EXPLORING COIMBRA

Away from the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Nova, the biennial offers a great opportunity to explore the historic city of Coimbra. The city dates to the Roman era, strategically positioned on a hill and along the main river between Braga and Lisbon. Passing through centuries of Suebi, Visigoth then Islamic rule, it was over the Middle Ages where much of the city’s grandeur of today arrived.

Religion brough monasteries and the city’s cathedral, while trading wealth led to the repair of the Roman bridge and construction of roads, pavements, fountains and an upgrade to the city walls. The 16th century façade of the Monastery of Santa Cruz stands proudly in the main town square, while the adjoining café offers a perfect spot to oversee not only the architecture but also the vibrant city life, perhaps while eating a crúzio pastry, a speciality of the café.

The city’s university originally began in 1308 after the king’s Studium Generale relocated from Lisbon, though relocated back a few decades later. In 1537, however, it landed in Coimbra permanently across the Royal complex, and to this day has been the main employer and lifeblood of a city known for academia and culture – Coimbra is known as A cidade dos estudantes or The city of the students.

Away from the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Nova, the biennial offers a great opportunity to explore the historic city of Coimbra. The city dates to the Roman era, strategically positioned on a hill and along the main river between Braga and Lisbon. Passing through centuries of Suebi, Visigoth then Islamic rule, it was over the Middle Ages where much of the city’s grandeur of today arrived.

Religion brough monasteries and the city’s cathedral, while trading wealth led to the repair of the Roman bridge and construction of roads, pavements, fountains and an upgrade to the city walls. The 16th century façade of the Monastery of Santa Cruz stands proudly in the main town square, while the adjoining café offers a perfect spot to oversee not only the architecture but also the vibrant city life, perhaps while eating a crúzio pastry, a speciality of the café.

The city’s university originally began in 1308 after the king’s Studium Generale relocated from Lisbon, though relocated back a few decades later. In 1537, however, it landed in Coimbra permanently across the Royal complex, and to this day has been the main employer and lifeblood of a city known for academia and culture – Coimbra is known as A cidade dos estudantes or The city of the students.

THE BIENNIAL IN HISTORIC SETTINGS

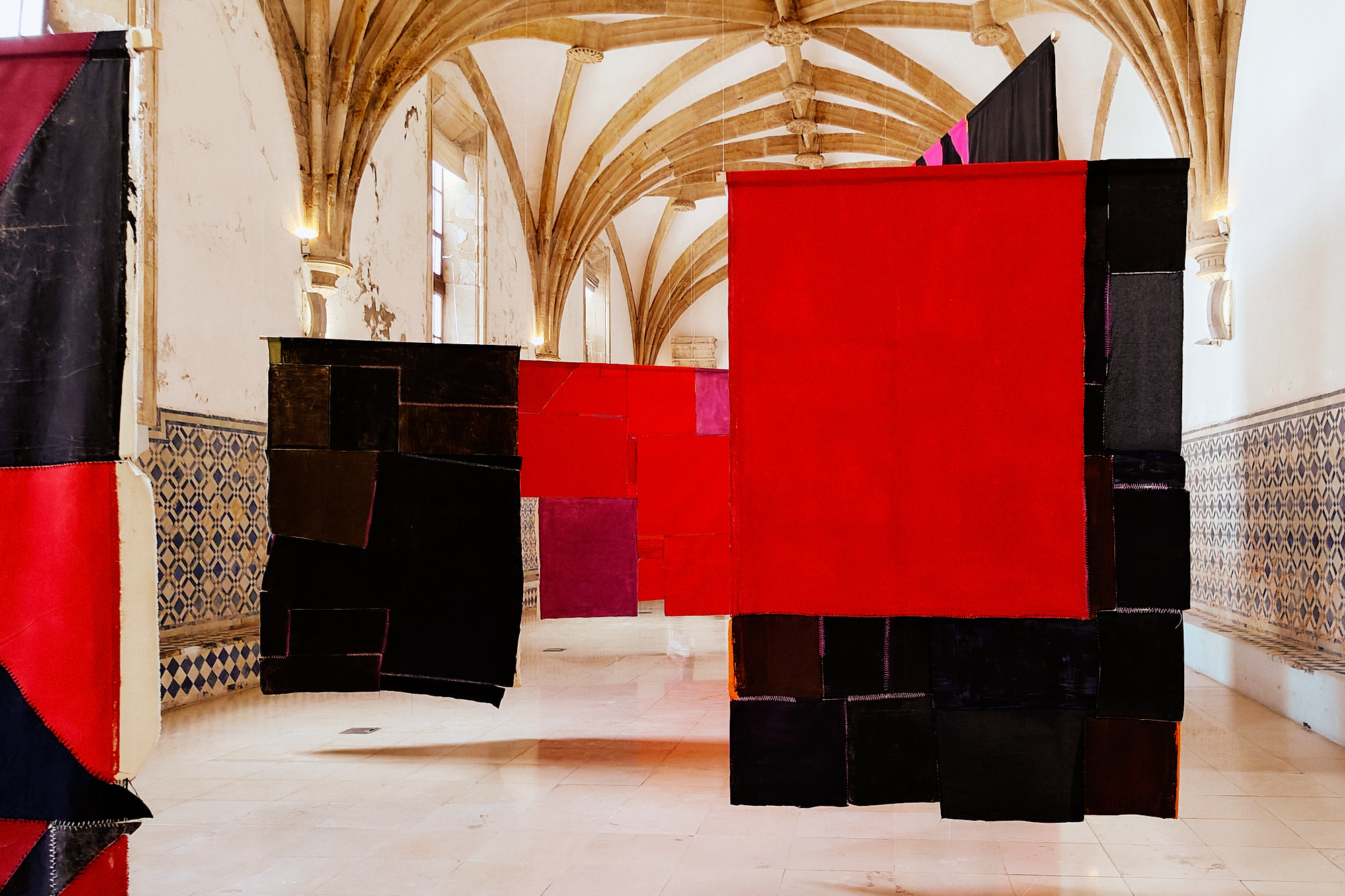

In the Old Refectory of the Monastery of Santa Cruz – now the City Room of the Museu Municipal de Coimbra – Spanish artist Teresa Lanceta’s radical textiles hang from the 16th century ribbed vaulted ceiling. In 1969 Lanceta moved to the Raval area of Barcelona, still a part of the city of mixed demographics and hotbed of politics, but then even more so with the artist enjoying the radical, bohemian culture glowing after the end of the Franco regime. She remained there until 1985, and these works, titled after the area, recall that period of urban, social, and political transition. Anarchist red and black is dominant, but these works are reflections as well as projection – hung so visitors can also see the tangled, stitched reverse side, emphasising the collective, nuanced detail that goes into such solid statements of force.

After crossing the lush green courtyard of the university’s Colégio das Artes, three rooms erupt with chaotic archive from Pedro G. Romero, his installation Scénario (2022-24) comprising 75 photographic panels, books, films, and assorted objects all hung around a ramshackle scaffolding. It’s immersive, and disquieting, the constant fight for visual, textual, historical, and political attention never letting the eye rest on one component. Art history is mixed with radical political history and mixed further with objects speaking to the history of Coimbra. It’s a sweet mess with many self-led routes through the material, one path being that of print-making and its connection both to an historic city printers and its use in the politics of change.

In the Old Refectory of the Monastery of Santa Cruz – now the City Room of the Museu Municipal de Coimbra – Spanish artist Teresa Lanceta’s radical textiles hang from the 16th century ribbed vaulted ceiling. In 1969 Lanceta moved to the Raval area of Barcelona, still a part of the city of mixed demographics and hotbed of politics, but then even more so with the artist enjoying the radical, bohemian culture glowing after the end of the Franco regime. She remained there until 1985, and these works, titled after the area, recall that period of urban, social, and political transition. Anarchist red and black is dominant, but these works are reflections as well as projection – hung so visitors can also see the tangled, stitched reverse side, emphasising the collective, nuanced detail that goes into such solid statements of force.

After crossing the lush green courtyard of the university’s Colégio das Artes, three rooms erupt with chaotic archive from Pedro G. Romero, his installation Scénario (2022-24) comprising 75 photographic panels, books, films, and assorted objects all hung around a ramshackle scaffolding. It’s immersive, and disquieting, the constant fight for visual, textual, historical, and political attention never letting the eye rest on one component. Art history is mixed with radical political history and mixed further with objects speaking to the history of Coimbra. It’s a sweet mess with many self-led routes through the material, one path being that of print-making and its connection both to an historic city printers and its use in the politics of change.

COIMBRA’s ROYAL PALACE COMPLEX

Taking a break from the contemporary interjections across the city, there’s plenty of much older creativity to explore. Much is located around the Royal Palace complex, now part of the university complex at the heart of the city. Here, around a grand square at the highpoint of Coimbra area are some of the highlights of the city’s UNESCO status. The Throne Room of the palace has an intensely decorative panelled ceiling with portraits of Portugal’s kings up to the 17th century watching from the walls. Next door, the Capela de São Miguel is a gold-leafed jewel box of a chapel, dating from the 11th century but with a 1500s-and-later refit that is present today. An ornate painted ceiling and rich blue azulejo tiling is somewhat dominated by an enormous baroque organ that appears to grow from the wall like a fungus.

All these rich interiors seem positively refined when compared with Biblioteca Joanina, one of the finest examples of Portuguese Baroque. Completed in 1728, it holds 60,000 books across two open floors formed of richly carved South American exotic wood with Chinoiserie motifs – this architecture is a statement of empire. It is said that bats are released inside at night, to help protect the historic building and books from mice – while underneath the library is an academic prison!

Outside, the grand central square offers views towards the 18th century clocktower and passage through the 17th century Porta Férrea towards the positively more modernist university complex rooted in the period of António de Oliveira Salazar, Prime Minister-cum-Dictator of Portugal who studied in Coimbra. In the square is another work by Yonamine stands – a sandbag enclave with maritime-code flags spelling a racist Greek pejorative expression, a reference to refugees travelling the sea who often disappear without trace.

Taking a break from the contemporary interjections across the city, there’s plenty of much older creativity to explore. Much is located around the Royal Palace complex, now part of the university complex at the heart of the city. Here, around a grand square at the highpoint of Coimbra area are some of the highlights of the city’s UNESCO status. The Throne Room of the palace has an intensely decorative panelled ceiling with portraits of Portugal’s kings up to the 17th century watching from the walls. Next door, the Capela de São Miguel is a gold-leafed jewel box of a chapel, dating from the 11th century but with a 1500s-and-later refit that is present today. An ornate painted ceiling and rich blue azulejo tiling is somewhat dominated by an enormous baroque organ that appears to grow from the wall like a fungus.

All these rich interiors seem positively refined when compared with Biblioteca Joanina, one of the finest examples of Portuguese Baroque. Completed in 1728, it holds 60,000 books across two open floors formed of richly carved South American exotic wood with Chinoiserie motifs – this architecture is a statement of empire. It is said that bats are released inside at night, to help protect the historic building and books from mice – while underneath the library is an academic prison!

Outside, the grand central square offers views towards the 18th century clocktower and passage through the 17th century Porta Férrea towards the positively more modernist university complex rooted in the period of António de Oliveira Salazar, Prime Minister-cum-Dictator of Portugal who studied in Coimbra. In the square is another work by Yonamine stands – a sandbag enclave with maritime-code flags spelling a racist Greek pejorative expression, a reference to refugees travelling the sea who often disappear without trace.

ANCIENT ROME UNDER YOUR FEET

The Machado de Castro National Museum is housed in the former Bishop’s Palace, entered via a Moorish portal opening onto a square with a Renaissance loggia with views across the city. Its extension by Gonçalo Byrne Arquitectos won the 2014 Piranesi/Prix de Rome prize, and offers a neatly detailed and lit way to explore both the rich art collection as well as the large remains of the Roman forum and cryptoporticus within the building’s basement.

But architectural and urban history isn’t hard to find across Coimbra. The 12th century Romanesque church of St. Tiago, for example, could even be missed amongst such rich heritage and gilded glory, but is worth a mention for its simplicity and presence in the city since for over 1000 years. A building which has undergone modifications and additions over the centuries, including the south portal which dates from the 1100s, its statuesque simplicity is striking.

The Machado de Castro National Museum is housed in the former Bishop’s Palace, entered via a Moorish portal opening onto a square with a Renaissance loggia with views across the city. Its extension by Gonçalo Byrne Arquitectos won the 2014 Piranesi/Prix de Rome prize, and offers a neatly detailed and lit way to explore both the rich art collection as well as the large remains of the Roman forum and cryptoporticus within the building’s basement.

But architectural and urban history isn’t hard to find across Coimbra. The 12th century Romanesque church of St. Tiago, for example, could even be missed amongst such rich heritage and gilded glory, but is worth a mention for its simplicity and presence in the city since for over 1000 years. A building which has undergone modifications and additions over the centuries, including the south portal which dates from the 1100s, its statuesque simplicity is striking.

A REST IN THE BOTANICAL GARDENS

The Jardim Botânico de Coimbra offers a green respite from the dense urban streets of the historic city core. Founded in 1772, with original plans taking the Chelsea Physic Garden as inspiration. Across 13 hectares and fronted by a tropical greenhouse it’s offers not only a relaxing break from the city, but a space of scientific and horticultural study for the university.

For the biennal, the greenhouse – and the plants within – inspired a new work from British artist Jeremy Deller. A trademark text banner work, it lists six recently extinct botanical species that staff of the gardens told the artist after he asked them which they miss the most. On the other side, the phrase Speak to the Earth and it will tell you proposes new relationships to nature, and perhaps a call for fewer future extinctions.

The Jardim Botânico de Coimbra offers a green respite from the dense urban streets of the historic city core. Founded in 1772, with original plans taking the Chelsea Physic Garden as inspiration. Across 13 hectares and fronted by a tropical greenhouse it’s offers not only a relaxing break from the city, but a space of scientific and horticultural study for the university.

For the biennal, the greenhouse – and the plants within – inspired a new work from British artist Jeremy Deller. A trademark text banner work, it lists six recently extinct botanical species that staff of the gardens told the artist after he asked them which they miss the most. On the other side, the phrase Speak to the Earth and it will tell you proposes new relationships to nature, and perhaps a call for fewer future extinctions.

BEYOND COIMBRA

ANOZERO, Bienal de Arte Contemporânea de Coimbra continues across other sites in the city with works teasing answers and ideas from its title, The Phantom of Liberty. Easily reached by train from Lisbon and Porto, the city also offers a useful central base to explore the wider municipality, including the Serra do Buçaco mountain range, vineyards, the castle of Montemor-o-Velho, and the seaside city of Figueira da Foz.

The biennial runs through to 30 June with fringe events and installations across the city as well as the core artistic presentations.

ANOZERO, Bienal de Arte Contemporânea de Coimbra continues across other sites in the city with works teasing answers and ideas from its title, The Phantom of Liberty. Easily reached by train from Lisbon and Porto, the city also offers a useful central base to explore the wider municipality, including the Serra do Buçaco mountain range, vineyards, the castle of Montemor-o-Velho, and the seaside city of Figueira da Foz.

The biennial runs through to 30 June with fringe events and installations across the city as well as the core artistic presentations.

ANOZERO – the Coimbra Biennial of Contemporary Art has been recognised as Portugal’s most important contemporary art biennial, with an average of 90,000 visitors to each edition. Initially created to promote a reflection on the classification of the University of Coimbra, Alta and Sofia as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in

2013, the Biennial proposes a confrontation between contemporary art and cultural heritage,

exploring the risks and multiple possibilities associated with the latter. Anozero is, therefore, an

action programme for the city that systematically questions the territory in which it is located to contribute to constructing an active and transformative cultural epoch. The Global South’s artists, curatorial, and social practices have been brought into this debate by the biennial,

amplified by the convergent programme and educational service promoted by Anozero. The name Anozero was chosen to represent the idea of the possibility of renewing— every two

years—a necessarily updated and dynamic new cycle of reflection.

www.geral.anozero-bienaldecoimbra.pt

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info

visit

ANOZERO – the Coimbra Biennial of Contemporary Art - The Phantom of Liberty - runs through to 30 June. Further details available from the biennal website: www.ofantasmadaliberdade.anozero-bienaldecoimbra.pt/en

Accomodation for this recessed.space visit to Coimbra was kindly supported by the Turismo do Centro - Center of Portugal.

images

All images © Will Jennings.

publication date

29 April 2024

tags

Anezoro, Angola, Coimbra, Baroque, Diego Biachi,

Biblioteca Joanina, Ángel Calvo Ulloa,

Capela de São Miguel, Carnation revolution, Mauro Cerqueira,

Jeremy Deller, Patricia Gómez, Filipe

Feijão, Gonçalo Byrne Arquitectos,

Jardim Botânico de Coimbra, Will Jennings,

María Jesús González, Teresa Lanceta,

João Marçal, Marta Mestre, Berio Molina,

Palace, Adam Pendleton, Portugal, Sandra

Poulson, Renaissance, Revolution, Roman, Romanesque, Pedro G. Romero,

António de Oliveira Salazar, Susanne Themlitz,

Travel, UNESCO

Accomodation for this recessed.space visit to Coimbra was kindly supported by the Turismo do Centro - Center of Portugal.

images