Research, design & construction combine at Vitra for Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House

Vitra Design Museum is a theme park of starchitect-designed buildings, each shouting for attention. Now, a Garden Pavilion by Tsuyoshi Tane set against a Piet Oudolf garden changes the agenda. James Haynes visited the building, garden & took a look at the accompanying exhibition & book to find out more.

As an ensemble of lauded

contemporary architecture, the Vitra Campus, located in Weil am Rhein, Switzerland, is no stranger to architectural

imagination. Since its inception in 1981 and the departure from the

corporatised aesthetic of Nicholas Grimshaw’s original plan, the Campus has

become a temple to the great and the good of the architectural world. To

its north the visitor encounters Frank Gehry’s Design Museum, a structure that

impressively weds function and form, while to the south, works by Herzog &

de Meuron, Zaha Hadid, and Alvaro Siza sit gracefully together. The Campus is

an architectural theme park, an exhibition space for starchitects, and

until recently, a celebrant of extractive construction.

![]()

![]()

Aside from its reputation as an anchor of contemporary culture, Vitra and its emeritus Chair Rolf Fehlbaum have long been recognised for their emblematic position at the precipice of our contemporary zeitgeist, informing and opining aesthetic direction. Thus, a shift in approach in recent years, responding to our current climatic paradigm, is welcome. A garden by designer Piet Oudolf proves illustrative, marking the organisation’s first effort to rebalance the relationship of the Campus to its surroundings. 4000m2 and completed in 2020, the work fell under the aspiration of adding a “fresh dimension” to the Campus and opening up a new, ever-changing experience for visitors.” Resultantly, the garden represents something different, it marks an embrace of the subtle, of the possibility for design and architectures – that despite drawing fanfare – are capable of expressing indifference to sitting centre stage. The apathy of Oudolf’s design to the built structures within its landscape illustrates this and captures real attention.

![]()

![]()

The Tane Garden House, completed in 2023, is a continuation of this new design approach. Designed by Paris-based Japanese architect Tsuyoshi Tane, it sits against Oudolf’s Garden and takes on a pavilion-like form, a real fracture from the language of its monolithic neighbours. Although smaller works by the likes of Buckminster Fuller and Kazuo Shinohara are peppered across the Campus, the language of Tane’s architecture feels different, more vernacular, and a little more specific to its place and time. Collaboration undoubtably informs this, with the Garden House more an outcome of conversation rather than a single voice. In the narrative that accompanies the physical fabric, Fehlbaum works hard to make this point, positioning the structures designer as akin to composer rather than eminent soloist.

![]()

![]()

The rich language of references developed throughout the project is testimony to this collaborative approach with learning made through looking, talking, and engagement driven by sharing – the hundreds of models produced throughout the project’s extended development, and which were featured in an exhibition earlier this year, mark the pinnacle of this approach. Despite the position of models as a stable within architectural projects – with exhibitions and texts dedicated to this approach – the breadth produced during the design of the Tane Garden House is exceptional. Here, the models were used to the full, rejecting a mere representational role, instead as fundamental tools for thought and iterative working.

Beginning with a series of sketch forms to understand the shape the structure might take, Tane and his team built a language, assigning both cute names to each piece and producing a coherent syntax, an expression distinct to both the project and its form. Later developments playfully built on this, using further forms to understand the structure’s interior, its impact with the ground, and the pitch of its roof. Although different, each case demonstrates a seriousness of intent, yet an understanding of the importance of play within design. A series of models examining the design of the staircase achieves this in a particularly impressive fashion, demonstrating not only a pursuit of simple and rational solution but for an architecture that’s interesting by its difference, but also suited to its context.

![]()

![]()

The completed architecture reflects this effort, blending a considered material palette with a form that weaves reference, context, and subtlety with understated flare. Sitting atop a series of marble pedestals, the bulk of the structure floats above the ground, reinforcing the notion of climate as central to the design process and the thinking through which it was formed. Similarly, a thatched exterior offers a stark foil to concrete surroundings while also exuding a colour palette that sits kindly with the garden it serves.

As principally a utilitarian structure – the Garden House is primarily designed to store gardening tools and offer space for workers attending nearby beehives – the building also supports a viewing platform for visitors to enjoy views of the Oudolf Garden. Although relatively simple, Tane and his collaborators have achieved this with much success, with neither building or garden feeling subservient to the other. The subtle pitch of the interior roof, also serving as the viewing platform railings, is perhaps the best example of this. Here, the design successfully meets both requirements without either feeling half-baked. Similarly, a series of windows puncturing the façade maintain a thoughtful relationship between workers and visitors, offering a literal window to their world, without providing ground for a full invasion.

![]()

![]()

In a manner suited to this blending of worlds, a small, yet impactful exhibition marked the pavilion’s launch within Frank Gehry’s Vitra Design Museum Gallery and Gatehouse, a display that felt composed yet unvetted. Filling a single space, the material presented initially read as a dazzling collage of process and intent. Models peppered the room. Images plastered the walls. Text was hidden throughout the array. In the busyness of the material, there was a real sense of ideas coming together and the effort taken to unpack the questions presented throughout the design process. A text by Fehlbaum, the commissioner of the work, added further weight in setting Tane’s structure and process apart.

Despite the exhibition’s eclectic, cloud-like presentation which ultimately produced a form that broke with the more common ordered schematic, the narratives embedded within the display added a real richness to the architecture and its design process. The images displaying a plush tapestry of references were particularly facilitative. While of its own place and time, the contextualisation of the pavilion against the wider canon of the Swiss vernacular, in particular in relation to structures at the open-air museum Ballenberg, further emphasises the effort to break from a language that is now a staple of Vitra. Clear, as with the structure’s aim, is an attempt to break with the methods of old.

![]()

![]()

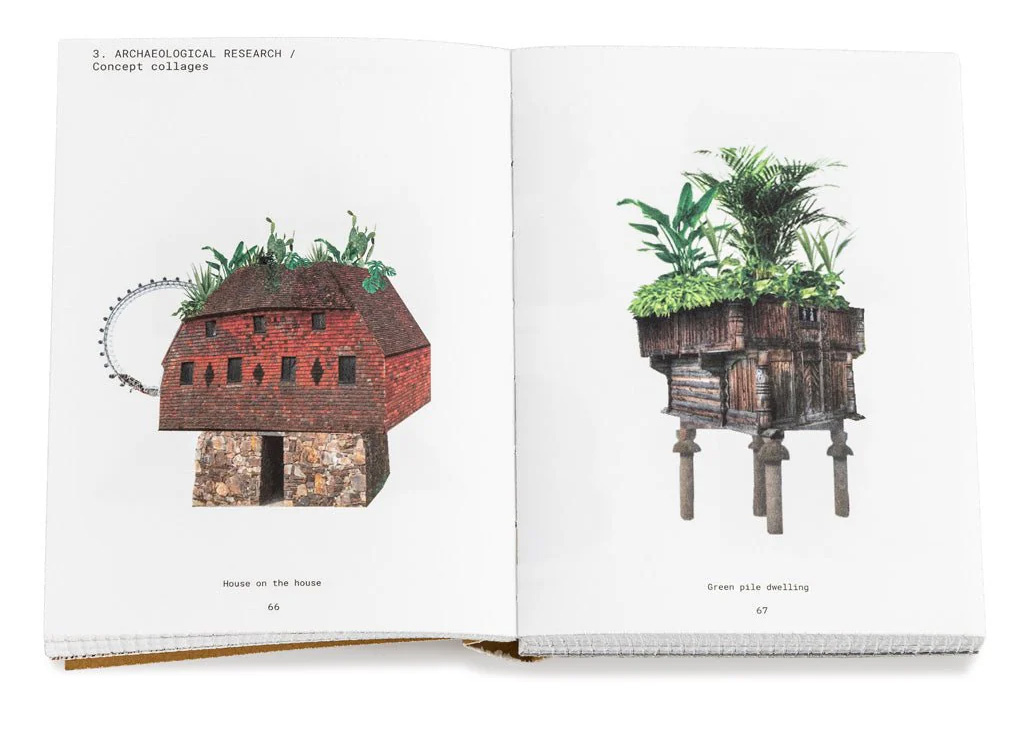

A considered publication accompanied this exhibition and the Tane Garden House itself, which not only consolidates the exhibition into a petite form, but also attaches a greater weight to the structure. Aesthetically, the inherent roughness of the exhibition carries through, folding the text into more of a didactic experience – perhaps paralleling the thatch that dons Tane’s structures. Although chaptered, the eclectic (yet highly curated and designed) imagery and its thoughtful placement breaks the potential for a metronomic format, instead providing an experience registerable as a continuum. Research, design, and construction combine, only occasionally broken by pauses filled with short narratives that prove instructive rather than overly domineering.

The focus is on images, drawings and the planned occasions where they meet. Consequently, the book becomes more of a presentation of process rather than result, it aims in format and content, to demonstrate, document, and mimic Tane’s approach. Again, Tane’s models’ surface and command attention as an undoubtable high point. In their presentation, they feel raw and inquisitive – the reader gets a sense of their importance, while their sheer quantity breaks the fourth wall, laying Tane’s thinking bare.

Also of note is the inclusion of the project team within the publication. Despite being hidden at the rear, its presence feels apt and appropriate. It makes evident the approach taken to produce a different kind of architecture; a notion paramount to the project as the Campus’ first structure “developed under the new paradigm of the climate crisis.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

While the associated exhibition and texts add weight, the architecture of the Tane Garden House ultimately commands its position through its quality of design, despite its dwarfed scale amongst the architectural juggernauts within its surroundings. Through a process akin to the design of a piece of furniture, Tsuyoshi Tane has crafted an architectural response that harnesses the joy within details, considered materially, and utilitarian purpose. Although, there is still much to be done to shift architecture’s model of operation, Tane’s efforts at Vitra represent a real sounding of the gun, illustrating the possibilities inherent within expanded modes of practice.

figs.i,ii

Aside from its reputation as an anchor of contemporary culture, Vitra and its emeritus Chair Rolf Fehlbaum have long been recognised for their emblematic position at the precipice of our contemporary zeitgeist, informing and opining aesthetic direction. Thus, a shift in approach in recent years, responding to our current climatic paradigm, is welcome. A garden by designer Piet Oudolf proves illustrative, marking the organisation’s first effort to rebalance the relationship of the Campus to its surroundings. 4000m2 and completed in 2020, the work fell under the aspiration of adding a “fresh dimension” to the Campus and opening up a new, ever-changing experience for visitors.” Resultantly, the garden represents something different, it marks an embrace of the subtle, of the possibility for design and architectures – that despite drawing fanfare – are capable of expressing indifference to sitting centre stage. The apathy of Oudolf’s design to the built structures within its landscape illustrates this and captures real attention.

figs.iii,iv

The Tane Garden House, completed in 2023, is a continuation of this new design approach. Designed by Paris-based Japanese architect Tsuyoshi Tane, it sits against Oudolf’s Garden and takes on a pavilion-like form, a real fracture from the language of its monolithic neighbours. Although smaller works by the likes of Buckminster Fuller and Kazuo Shinohara are peppered across the Campus, the language of Tane’s architecture feels different, more vernacular, and a little more specific to its place and time. Collaboration undoubtably informs this, with the Garden House more an outcome of conversation rather than a single voice. In the narrative that accompanies the physical fabric, Fehlbaum works hard to make this point, positioning the structures designer as akin to composer rather than eminent soloist.

figs.v,vi

The rich language of references developed throughout the project is testimony to this collaborative approach with learning made through looking, talking, and engagement driven by sharing – the hundreds of models produced throughout the project’s extended development, and which were featured in an exhibition earlier this year, mark the pinnacle of this approach. Despite the position of models as a stable within architectural projects – with exhibitions and texts dedicated to this approach – the breadth produced during the design of the Tane Garden House is exceptional. Here, the models were used to the full, rejecting a mere representational role, instead as fundamental tools for thought and iterative working.

Beginning with a series of sketch forms to understand the shape the structure might take, Tane and his team built a language, assigning both cute names to each piece and producing a coherent syntax, an expression distinct to both the project and its form. Later developments playfully built on this, using further forms to understand the structure’s interior, its impact with the ground, and the pitch of its roof. Although different, each case demonstrates a seriousness of intent, yet an understanding of the importance of play within design. A series of models examining the design of the staircase achieves this in a particularly impressive fashion, demonstrating not only a pursuit of simple and rational solution but for an architecture that’s interesting by its difference, but also suited to its context.

figs.vii,viii

The completed architecture reflects this effort, blending a considered material palette with a form that weaves reference, context, and subtlety with understated flare. Sitting atop a series of marble pedestals, the bulk of the structure floats above the ground, reinforcing the notion of climate as central to the design process and the thinking through which it was formed. Similarly, a thatched exterior offers a stark foil to concrete surroundings while also exuding a colour palette that sits kindly with the garden it serves.

As principally a utilitarian structure – the Garden House is primarily designed to store gardening tools and offer space for workers attending nearby beehives – the building also supports a viewing platform for visitors to enjoy views of the Oudolf Garden. Although relatively simple, Tane and his collaborators have achieved this with much success, with neither building or garden feeling subservient to the other. The subtle pitch of the interior roof, also serving as the viewing platform railings, is perhaps the best example of this. Here, the design successfully meets both requirements without either feeling half-baked. Similarly, a series of windows puncturing the façade maintain a thoughtful relationship between workers and visitors, offering a literal window to their world, without providing ground for a full invasion.

figs.ix,x

In a manner suited to this blending of worlds, a small, yet impactful exhibition marked the pavilion’s launch within Frank Gehry’s Vitra Design Museum Gallery and Gatehouse, a display that felt composed yet unvetted. Filling a single space, the material presented initially read as a dazzling collage of process and intent. Models peppered the room. Images plastered the walls. Text was hidden throughout the array. In the busyness of the material, there was a real sense of ideas coming together and the effort taken to unpack the questions presented throughout the design process. A text by Fehlbaum, the commissioner of the work, added further weight in setting Tane’s structure and process apart.

Despite the exhibition’s eclectic, cloud-like presentation which ultimately produced a form that broke with the more common ordered schematic, the narratives embedded within the display added a real richness to the architecture and its design process. The images displaying a plush tapestry of references were particularly facilitative. While of its own place and time, the contextualisation of the pavilion against the wider canon of the Swiss vernacular, in particular in relation to structures at the open-air museum Ballenberg, further emphasises the effort to break from a language that is now a staple of Vitra. Clear, as with the structure’s aim, is an attempt to break with the methods of old.

figs.xi,xii

A considered publication accompanied this exhibition and the Tane Garden House itself, which not only consolidates the exhibition into a petite form, but also attaches a greater weight to the structure. Aesthetically, the inherent roughness of the exhibition carries through, folding the text into more of a didactic experience – perhaps paralleling the thatch that dons Tane’s structures. Although chaptered, the eclectic (yet highly curated and designed) imagery and its thoughtful placement breaks the potential for a metronomic format, instead providing an experience registerable as a continuum. Research, design, and construction combine, only occasionally broken by pauses filled with short narratives that prove instructive rather than overly domineering.

The focus is on images, drawings and the planned occasions where they meet. Consequently, the book becomes more of a presentation of process rather than result, it aims in format and content, to demonstrate, document, and mimic Tane’s approach. Again, Tane’s models’ surface and command attention as an undoubtable high point. In their presentation, they feel raw and inquisitive – the reader gets a sense of their importance, while their sheer quantity breaks the fourth wall, laying Tane’s thinking bare.

Also of note is the inclusion of the project team within the publication. Despite being hidden at the rear, its presence feels apt and appropriate. It makes evident the approach taken to produce a different kind of architecture; a notion paramount to the project as the Campus’ first structure “developed under the new paradigm of the climate crisis.”

figs.xiii-xv

While the associated exhibition and texts add weight, the architecture of the Tane Garden House ultimately commands its position through its quality of design, despite its dwarfed scale amongst the architectural juggernauts within its surroundings. Through a process akin to the design of a piece of furniture, Tsuyoshi Tane has crafted an architectural response that harnesses the joy within details, considered materially, and utilitarian purpose. Although, there is still much to be done to shift architecture’s model of operation, Tane’s efforts at Vitra represent a real sounding of the gun, illustrating the possibilities inherent within expanded modes of practice.

Tsuyoshi Tane was born in Tokyo in 1979. After establishing ATTA-Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane Architects in 2017, he has been based in Paris. He has formed the basis of his core architectural concept, “Archaeology of the Future,” on the idea that memories are embedded in a place. He is currently engaged in a wide range of projects concentrated in Europe and Japan. His major works include Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art (2020), Tane Garden House for Vitra Campus, and new main building of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, due for completion in 2036.

www.at-ta.fr

The Vitra Design Museum numbers among the world's leading museums of design. It is dedicated to the research and presentation of design, past and present, and examines design's relationship to architecture, art and everyday culture. In the main museum building by Frank Gehry, the museum annually mounts two major temporary exhibitions, such as Plastic: Remaking Our World (2022), Here We Are! Women in Design 1900 – Today (2021), Home Stories: 100 Years, 20 Visionary Interiors (2020), Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today (2019), Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People (2019), or Charles & Ray Eames. The Power of Design (2017/18). In addition, smaller shows are presented in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery, which often follow a more contemporary and experimental approach.

The Vitra Schaudepot which was designed by Herzog & de Meuron, presents approximately 400 key objects from the extensive collection and hence resembles one of the largest permanent collections and research sites on modern furniture design world-wide. The annual presentation at the Vitra Schaudepot reveals the collection in a fresh light every year. Often developed with renowned designers, many of the museum's exhibitions cover highly relevant contemporary themes, such as future technologies, sustainability or questions like mobility and social responsibility. Others are presenting historical topics or monographic exhibitions on iconic designers.

The work of the Vitra Design Museum is based on its collection, which includes not only key objects of design history, but also the estates of several important design personalities. The museum library and document archive are available to researchers upon request. The museum conceives its exhibitions for touring, and they are shown at venues around the world. On the Vitra Campus, they are complemented by a diverse programme of events, guided tours, and workshops.

www.design-museum.de

James Haynes graduated from the Edinburgh School of

Architecture and Landscape Architecture (ESALA) in 2022 and until recently

worked as an architectural assistant for the artist Do Ho Suh. Alongside his

previous role and studies, James has developed a keen interest in architectural

writing and research, which has found an opportunity for expression through

support from the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland and through

involvement with several publications: the RIBAJ, RIAS Quarterly, Architecture

Ireland and others. Upon graduating, James received the ESALA MA Architecture

Prize and his thesis project, A Tober: An Architecture of Resilience and Joy,

received the ESALA nomination for RIBA Bronze Medal. At present, James is

undertaking a funded MScR at the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape

Architecture (ESALA) before beginning a M.Arch at Cornell University in 2025.

www.instagram.com/james.haynes73

The Vitra Schaudepot which was designed by Herzog & de Meuron, presents approximately 400 key objects from the extensive collection and hence resembles one of the largest permanent collections and research sites on modern furniture design world-wide. The annual presentation at the Vitra Schaudepot reveals the collection in a fresh light every year. Often developed with renowned designers, many of the museum's exhibitions cover highly relevant contemporary themes, such as future technologies, sustainability or questions like mobility and social responsibility. Others are presenting historical topics or monographic exhibitions on iconic designers.

The work of the Vitra Design Museum is based on its collection, which includes not only key objects of design history, but also the estates of several important design personalities. The museum library and document archive are available to researchers upon request. The museum conceives its exhibitions for touring, and they are shown at venues around the world. On the Vitra Campus, they are complemented by a diverse programme of events, guided tours, and workshops.

www.design-museum.de

James Haynes graduated from the Edinburgh School of

Architecture and Landscape Architecture (ESALA) in 2022 and until recently

worked as an architectural assistant for the artist Do Ho Suh. Alongside his

previous role and studies, James has developed a keen interest in architectural

writing and research, which has found an opportunity for expression through

support from the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland and through

involvement with several publications: the RIBAJ, RIAS Quarterly, Architecture

Ireland and others. Upon graduating, James received the ESALA MA Architecture

Prize and his thesis project, A Tober: An Architecture of Resilience and Joy,

received the ESALA nomination for RIBA Bronze Medal. At present, James is

undertaking a funded MScR at the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape

Architecture (ESALA) before beginning a M.Arch at Cornell University in 2025.

www.instagram.com/james.haynes73

visit/buy

The exhibition Tsyoshi Tane: The Garden House has ended, but details of current and upcoming exhibitions at Vitra Design Museum can be found here: www.design-museum.de

The book Tane Garden House is published by Vitra Design Museum and can be purchesed from all good bookshops or from the museum website here: www.shop.design-museum.de/en/products/tane-garden-house

images

fig.i Vitra Design Museum, Frank Gehry (1989).

© Vitra Design Museum, photograph by Bettina Matthiessen.

fig.ii Sed consequat ante eget magna rhoncus ultricies laoreet sit amet odio. © Lorem Ipsum

figs.ii-iv,ix Tane Garden House, Vitra Campus, 2023 © Vitra / ATTA, photo: Julien Lanoo.

fig.v Volume models, scale: 1:30 © Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane Architects, Paris.

fig.vi Site model, scale: 1:30.

© Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane Architects, Paris.

fig.vii 7Concept/volume study models. © Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane Architects, Paris.

fig.viii Installation view “Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House” © Vitra Design Museum Photo: Mark Niedermann.

fig.x “Archaeological research” as part of the project preparation

© Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane Architects, Paris.

figs.xi,xii Installation view, “Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House”. © Vitra Design Museum Photo: Mark Niedermann.

figs.xiii-xv “Tane Garden House” by Rolf Fehlbaum & Tsuyoshi Tane (2023), pubished by Vitra Design Museum.

publication date

03 July 2024

tags

Collaboration, Rolf Fehlbaum, Richard Buckminster Fuller, Herzog & de Meuron, Garden, Frank Gehry, Nicholas Grimshaw, Zaha Hadid, James Haynes, Model, Piet Oudolf, Pavilion, Process, Kazuo Shinohara, Alvaro Siza, Tane Garden House, Thatch, Tsuyoshi Tane, Vitra Design Museum

The book Tane Garden House is published by Vitra Design Museum and can be purchesed from all good bookshops or from the museum website here: www.shop.design-museum.de/en/products/tane-garden-house