Lynch Architects & glass artist Brian Clarke combine to

create spaces of calm depth at Westminster Coroner’s Court

With the refurbishment of a Victorian building &

unashamedly bold, modern extension, Lynch Architects have expanded Westminster

Coroner’s Court, providing not only more space but a deeper, reflective experience

for those who attend inquiries at the building. New stained-glass windows from artist

Brian Clarke flood poetic light into the spaces pregnant with symbolism, pause,

and poetry.

Lynch Architects have completed the renovation and extension

of Westminster Coroner’s Court, a Grade II listed late-Victorian building Horseferry

Road, London – a stone’s throw from Parliament and Westminster Abbey. The

extension is unashamedly present, not trying to mimic or silently subsume

into the existing architecture, and though the flat end of the barrel-vaulted

block is stark, it does not dominate or fight against the historic red-brick neighbour. Despite obvious differences between the old and new

components, there is a calming conversation and ease of relationship between

the two.

![]()

![]()

![]()

This careful consideration to volume and weight continues throughout. This is a building that must work at different registers, needing to announce its civicness to the street, but for bereaved families and friends of the deceased attending inquests – which include high profile cases such as the Grenfell Tower disaster as well as less publicised events – offering a sense of assuredness, safety, sanctity, and calm at a more intimate scale.

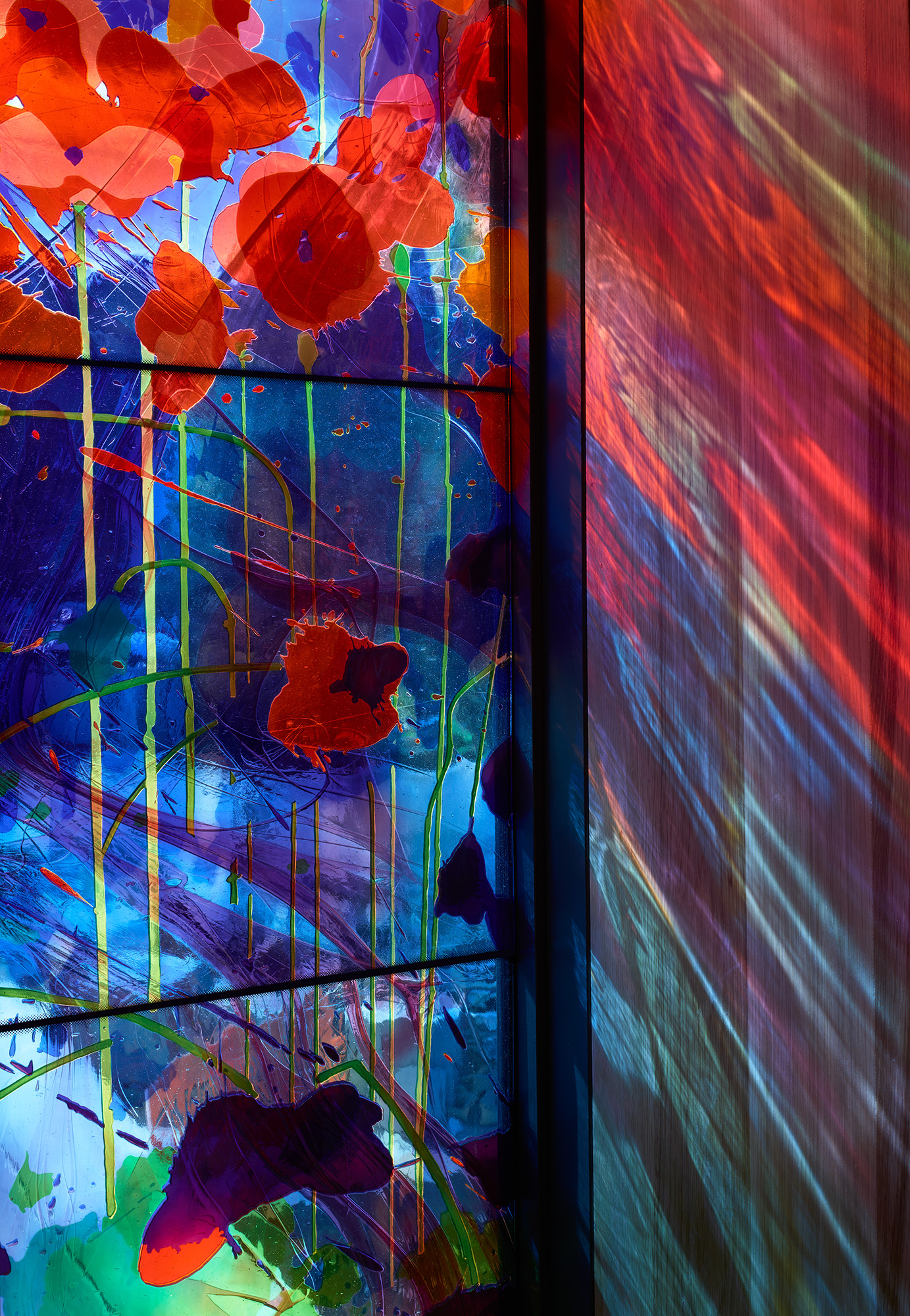

This is carried through the project with various strategies which at their best incorporate not only architectural but also artistic and landscaping elements. The scheme deploys a sombre and calming material palette throughout, there is intelligent use of natural light and an allowance of shadows, and series of windows by Brian Clarke, a leading contemporary artist who works with stained glass, spills moments of diffracted colour into spaces within.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In many ways, Westminster Coroner’s Court was a perfect commission for Lynch Architects, a firm that have recently completed two somewhat larger schemes a short distance away in the rapidly growing area around Victoria Station. n2 & Nova Place, a complex of three buildings sits behind and framing the Victoria Palace theatre, subtle kinks in the plan of higher stories and a shifting mathematical rhythm playing out across the façades of the different blocks adds a sense of the poetic to large masses. Down the road, the Zig Zag Building is a large mixed-use project taking up a long section of Victoria Street’s real estate, but where some developers may place a single block taking up the entire length, Lynch’s stuttering façade and further rhythmic play with vertical fins, allow for the scale of the building to appear less through shifting light, shade, and geometry.

Buildings of this scale, even with strong detailing and considered poetry, work at a different urban and psychological scale to the Coroner’s Court. Zig Zag and Nova Place speak to the somewhat chaotic urban patchwork of the area, with good consideration to street-level touches but for the most part existing high above the passerby. The Coroner’s Court had to have a different relationship, speaking more to the human condition in scale, form, and feeling. It does this externally, with the new extension a clear statement in the street but not in any overpowering way, and moreso it does this internally, with sequences of carefully detailed spaces at an intimate and comforting scale.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The barrel vaulted extension carries a tomblike presence, but not in a daunting way. It references the Santa Maria dei Miracoli, one of the great Venetian churches that gently emerges from the sinuous passages and canals that lead to its tight Cannaregio square. The Coroner’s Court, however, is secular, and has not only stripped back Santa Maria’s Christian symbolism but also its rich ornamentation, here now offering itself up as a symbolic volume.

The interior is similarly stripped back, but with enough texture in the wooden floor, battened surfaces, and stone blocks to offer a warmth where such withdrawn spaces may act otherwise. This allows the moments of Clarke’s windows to sing even more, working twice: as flat panes of glass with clarity of image and colour, and then splayed across the architecture, where the colour and form of the artworks conflate with material.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Clarke had a major retrospective last year at Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery, a short walk from Westminster Coroner’s Court. There, the artist presented a series of freestanding panels, wall-mounted glass in frames, and hanging systems, many containing his recurring motifs of flowers and collage. The works stood powerfully in the white-walled space, but his work sings most richly when tightly involved with architecture, not just presented within it. Lynch Architects are not the first architects he has worked with. With a career spanning five decades, Clarke has already designed glass works for projects by I.M. Pei, Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid and more. His work can be seen in all kinds of building, from Saudi skyscrapers to a Holocaust Memorial Synagogue.

It is in projects like that last one, in Darmstadt, Germany that Clarke’s glass works best, where the interplay of light and form can carry reflective depth, and so it is at the Coroner’s Court that his windows offer moments of abstraction which might help those attending the building with their situation.

Outside, Lynch Architects have found space for a small garden, offering external respite for air and reflection. As with other elements of the design detail, it draws references from the bays, niches, and cornicing of the historic building it abuts. A salvaged limestone fountain adds a gentle noise and touch of history to the new sandstone paving and precast concrete forms, all softened with planting designed by Richard Nye. The void of an empty recessed arch watches over, its absence poetically present.

![]()

Figs.i-iii

This careful consideration to volume and weight continues throughout. This is a building that must work at different registers, needing to announce its civicness to the street, but for bereaved families and friends of the deceased attending inquests – which include high profile cases such as the Grenfell Tower disaster as well as less publicised events – offering a sense of assuredness, safety, sanctity, and calm at a more intimate scale.

This is carried through the project with various strategies which at their best incorporate not only architectural but also artistic and landscaping elements. The scheme deploys a sombre and calming material palette throughout, there is intelligent use of natural light and an allowance of shadows, and series of windows by Brian Clarke, a leading contemporary artist who works with stained glass, spills moments of diffracted colour into spaces within.

Figs.iv-vii

In many ways, Westminster Coroner’s Court was a perfect commission for Lynch Architects, a firm that have recently completed two somewhat larger schemes a short distance away in the rapidly growing area around Victoria Station. n2 & Nova Place, a complex of three buildings sits behind and framing the Victoria Palace theatre, subtle kinks in the plan of higher stories and a shifting mathematical rhythm playing out across the façades of the different blocks adds a sense of the poetic to large masses. Down the road, the Zig Zag Building is a large mixed-use project taking up a long section of Victoria Street’s real estate, but where some developers may place a single block taking up the entire length, Lynch’s stuttering façade and further rhythmic play with vertical fins, allow for the scale of the building to appear less through shifting light, shade, and geometry.

Buildings of this scale, even with strong detailing and considered poetry, work at a different urban and psychological scale to the Coroner’s Court. Zig Zag and Nova Place speak to the somewhat chaotic urban patchwork of the area, with good consideration to street-level touches but for the most part existing high above the passerby. The Coroner’s Court had to have a different relationship, speaking more to the human condition in scale, form, and feeling. It does this externally, with the new extension a clear statement in the street but not in any overpowering way, and moreso it does this internally, with sequences of carefully detailed spaces at an intimate and comforting scale.

Figs.viii-xi

The barrel vaulted extension carries a tomblike presence, but not in a daunting way. It references the Santa Maria dei Miracoli, one of the great Venetian churches that gently emerges from the sinuous passages and canals that lead to its tight Cannaregio square. The Coroner’s Court, however, is secular, and has not only stripped back Santa Maria’s Christian symbolism but also its rich ornamentation, here now offering itself up as a symbolic volume.

The interior is similarly stripped back, but with enough texture in the wooden floor, battened surfaces, and stone blocks to offer a warmth where such withdrawn spaces may act otherwise. This allows the moments of Clarke’s windows to sing even more, working twice: as flat panes of glass with clarity of image and colour, and then splayed across the architecture, where the colour and form of the artworks conflate with material.

Figs. xii-xv

Clarke had a major retrospective last year at Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery, a short walk from Westminster Coroner’s Court. There, the artist presented a series of freestanding panels, wall-mounted glass in frames, and hanging systems, many containing his recurring motifs of flowers and collage. The works stood powerfully in the white-walled space, but his work sings most richly when tightly involved with architecture, not just presented within it. Lynch Architects are not the first architects he has worked with. With a career spanning five decades, Clarke has already designed glass works for projects by I.M. Pei, Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid and more. His work can be seen in all kinds of building, from Saudi skyscrapers to a Holocaust Memorial Synagogue.

It is in projects like that last one, in Darmstadt, Germany that Clarke’s glass works best, where the interplay of light and form can carry reflective depth, and so it is at the Coroner’s Court that his windows offer moments of abstraction which might help those attending the building with their situation.

Outside, Lynch Architects have found space for a small garden, offering external respite for air and reflection. As with other elements of the design detail, it draws references from the bays, niches, and cornicing of the historic building it abuts. A salvaged limestone fountain adds a gentle noise and touch of history to the new sandstone paving and precast concrete forms, all softened with planting designed by Richard Nye. The void of an empty recessed arch watches over, its absence poetically present.

Fig.xvi

Lynch Architects is a London-based RIBA Chartered practice that prides itself on providing imaginative and empathetic solutions to complex technical and cultural challenges. Marsh View, a house that the preactice crafted out of parts of a 1950s Norfolk bungalow between 2003-8, was described in The Observer by Stephen Bailey, as "masterpiece", and Ellis Woodman, the director of the Architecture Foundation, observed in the Architects Journal in 2016 that "Lynch Architects’ buildings at Victoria should see us all out." For the past 26 years Lynch Archtects have worked at almost every scale on nearly all types of building in every sector - from individual houses to social and private housing schemes, cultural and commercial projects, new-buildings and renovations. The practice has expertise and a deep interest in heritage and conservation design, and extensive academic and professional experience of working with listed buildings and in conservation areas. They have won a number of awards, including best office building at The World Architecture Festival in 2016, and publishers regularly seek us out to feature our work in architectural journals across the world. They were privileged to exhibit our residential, commercial and master-planning designs to our international peers at the Venice Biennale in 2008 and in 2012, and at the Milan Triennial in 2018. They believe in the craft of architecture, and that good design entails the search for a poetic economy of means.

As well as teaching and a commitment to working with teenagers within their community, they run a small publishing house from within the practice, Canalside Press, which publishes the Journal of Civic Architecture (JoCA) as well as books on the history of modern architecture, photography and poetry. Dr Patrick Lynch, the founding partner, has written a number of books, two of which are published by Artifice/Blackdog.

www.lyncharchitects.com

Brian Clarke is one of the most celebrated stained glass artists working today. Over his 50-year career, he has collaborated on projects and proposals with leading figures of architecture, from Zaha Hadid, I.M. Pei, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers to Norman Foster. He has exhibited his stained glass and paintings across the world, and continues to create meaningful interventions into historic sites, both sacred and secular.

Having won a Churchill Memorial Trust Fellowship in 1974, allowing him to visit important stained glass sites in France, Germany and Italy, in 1978 Clarke co-curated the seminal exhibition GLASS/LIGHT with artists John Piper and Marc Chagall, exploring the history and enduring relevance of stained glass. By the 1980s Clarke was working internationally and adapting his style and materials to each site. In Clarke’s words, ‘a complex multivalent space, redolent with symbols and imagery, requires a complex response’. For both the Royal Mosque at the King Khalid International Airport in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (1980-1982), and the refurbished Queen Victoria Street Arcade in Leeds, UK (1988-1990), Clarke turned to historic local tiling and glass for inspiration. Between 1992 and 1994, Clarke and architect Will Alsop collaborated on Le Grand Bleu, the headquarters and council chamber of the Hotel du département des Bouches-du-Rhône in Marseille, France, cladding the building in suitably Mediterranean ultramarine tones. His architectural projects and paintings came to form a mutual inspiration. Clarke exhibited his structural paintings in major international shows, from Brian Clarke: Paintings 1976-1987 at Seibu Museum, Tokyo, Japan (1987), to 80 artistes autour du Mondial at the Galerie Enrico Navarro, Paris, France (1998).

His sensitivity to site and collective memory also informs his spiritual commissions, including the Holocaust Memorial Synagogue (Neue Synagoge) in Darmstadt, Germany (1988), the Cistercian Abbaye de la Fille Dieu, Romont, Switzerland (1996) and the Papal Chapel at the Apostolic Nunciature, London, UK (2010). For the 13th-century Linköping Cathedral in Sweden (2005-2010), Clarke’s windows incorporated photographs that reinterpreted Christian iconography, yet were adapted to fit and preserve the cathedral’s original diamond-patterned 1850s windows, of great cultural and historical significance.

Clarke is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (1993), a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (1989) and an Honorary Liveryman at the Worshipful Company of Glaziers and Master Painters (2012). He is Sole Executor and Chair of the Estate of Francis Bacon (1998), and Chair and Executor of the Zaha Hadid Foundation (2016). In the King’s New Year Honours list 2024, he received a knighthood for his services to art – a title not known to have been given to a stained glass artist before. In 2024, Clarke received the Freedom of the City of London for his outstanding contributions to art.

www.brianclarke.co.uk

Having won a Churchill Memorial Trust Fellowship in 1974, allowing him to visit important stained glass sites in France, Germany and Italy, in 1978 Clarke co-curated the seminal exhibition GLASS/LIGHT with artists John Piper and Marc Chagall, exploring the history and enduring relevance of stained glass. By the 1980s Clarke was working internationally and adapting his style and materials to each site. In Clarke’s words, ‘a complex multivalent space, redolent with symbols and imagery, requires a complex response’. For both the Royal Mosque at the King Khalid International Airport in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (1980-1982), and the refurbished Queen Victoria Street Arcade in Leeds, UK (1988-1990), Clarke turned to historic local tiling and glass for inspiration. Between 1992 and 1994, Clarke and architect Will Alsop collaborated on Le Grand Bleu, the headquarters and council chamber of the Hotel du département des Bouches-du-Rhône in Marseille, France, cladding the building in suitably Mediterranean ultramarine tones. His architectural projects and paintings came to form a mutual inspiration. Clarke exhibited his structural paintings in major international shows, from Brian Clarke: Paintings 1976-1987 at Seibu Museum, Tokyo, Japan (1987), to 80 artistes autour du Mondial at the Galerie Enrico Navarro, Paris, France (1998).

His sensitivity to site and collective memory also informs his spiritual commissions, including the Holocaust Memorial Synagogue (Neue Synagoge) in Darmstadt, Germany (1988), the Cistercian Abbaye de la Fille Dieu, Romont, Switzerland (1996) and the Papal Chapel at the Apostolic Nunciature, London, UK (2010). For the 13th-century Linköping Cathedral in Sweden (2005-2010), Clarke’s windows incorporated photographs that reinterpreted Christian iconography, yet were adapted to fit and preserve the cathedral’s original diamond-patterned 1850s windows, of great cultural and historical significance.

Clarke is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (1993), a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (1989) and an Honorary Liveryman at the Worshipful Company of Glaziers and Master Painters (2012). He is Sole Executor and Chair of the Estate of Francis Bacon (1998), and Chair and Executor of the Zaha Hadid Foundation (2016). In the King’s New Year Honours list 2024, he received a knighthood for his services to art – a title not known to have been given to a stained glass artist before. In 2024, Clarke received the Freedom of the City of London for his outstanding contributions to art.

www.brianclarke.co.uk