Versions of

reality in a suspended state: James Lomax at Sid Motion Gallery

James Lomax’s

exhibition at Sid Motion Gallery can be seen in two ways. With sodium lights, on

the works are saturated & flattened in yellow, while at other times, in

white light, new depths can be read. Tom Denman visited to experience this switch

in reality & how it relates to Lomax’s recent residency at a HMP Grendon.

James Lomax

is an artist who makes us think about how our social position – including

especially the ways it rubs against space and place – affects our encounters

with objects and art. I came to his show at Sid Motion Gallery with the

knowledge that he had spent a considerable amount of time talking to prisoners

at HMP Grendon, as part of a residency organised by Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery,

and that a version of this show had already been held in the prison with very

restricted access, with most of its audience consisting of prisoners and prison

staff.

With this in mind, I was inclined to think that his exhibition at Sid Motion also had a form of restricted access, since, aside from the other social and circumstantial restrictions that limit attendance at an art gallery, prisoners would not have been lawfully able to see it. Even on my way to the gallery, I was aware of a serious, non-negotiable division of experience conjured by the image of the prison, an institution I had never stepped foot in.

![]()

![]()

One thing I can hazard to be sure of is that life in prison is starkly different from life outside it. If all our different experiences of life affect our perspective on it, incarceration exists as a solid – the most solid I can think of right now, along with war – differentiating factor. For me, imprisonment makes more immediate sense as a metaphor: I complain about feeling imprisoned if, for some reason, I don’t sense the freedom to do something I want to do – have a beer with lunch, swim in the sea in winter, improvise an afternoon away from my desk, roaming London’s galleries – even if these are self-imposed restrictions, and thus I am also the person who can lift them. Imprisonment, therefore, actually describes my freedom, if not also my entitlement.

The gallery is one floor up from ground level, divided into three openly interconnected areas, one wall is largely a warehouse window. And yet the atmosphere is stifling, not because of people, but suffusing every square inch of the space is a thick yellow light – the kind of lighting once used to illuminate alleys in Britain’s cities. I recall the sodium hue from police documentaries. It feels like gas, like a substance. It seems to stick to the skin, to everything, and everything is monochrome. The light is like one-point perspective, determining our standpoint, except in a way that pervades our entire frame of vision. I don’t think twice about assuming everything here is grey. People’s eyes are funny, vampire eyes. I am feeling slightly nauseous, attending to everyone around me, mentally, visually, with unusual intensity, as if I am needy of them. I can only think it’s the world closing in on us.

![]()

![]()

I have to keep reminding myself that the exhibition mainly consists of separate objects, all rectangular and all but one hanging on the walls – reliefs, photographs, and one sourced readymade. The latter hangs from the ceiling as a room divider, made of gridded plastic transparency. Its empty pockets were once used to advertise properties in a now-redundant estate agent’s window, and it still bears the fingerprints of hands changing properties.

The works, individually and as a whole, are experienced spatially, as enclosure. There is something in the way the reliefs – business envelopes strewn on plywood surfaces, except one which consists of an upright rose, all cast in concrete – push back. They forbid and block just as the light blocks their chromatic identity – or us from seeing it. There is something about Lomax’s use of concrete, which under the yellow light seems to work metaphorically, suppressing illusion, forbidding us from making the different components dance with our eyes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

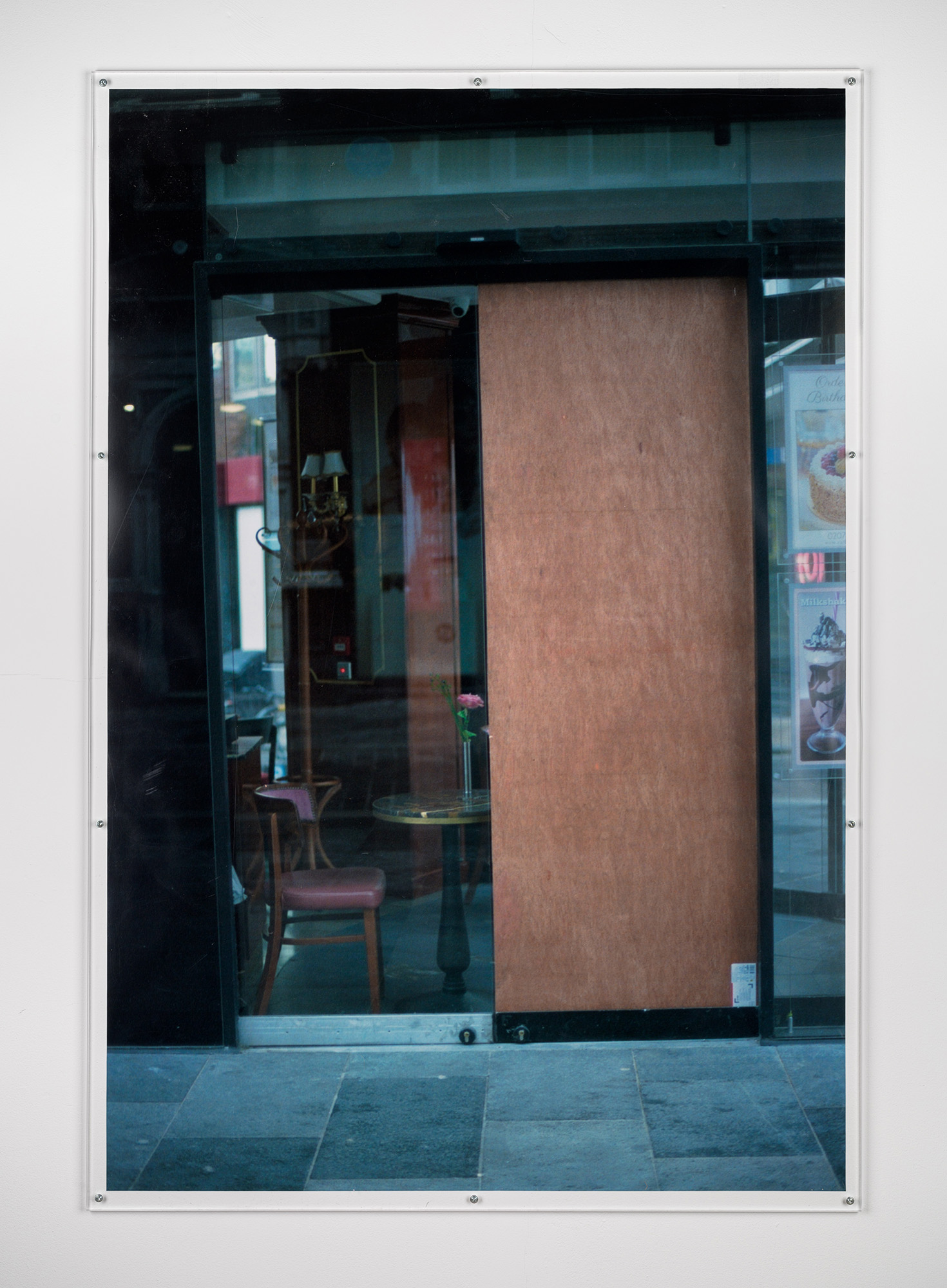

There is also something in the way the photographs of glass doors keep us out, their reflections suggesting a lack of light, or a nothingness, therein. If we see ourselves, or imagine ourselves, reflected in the almost life-size images, we might feel as if trapped between the illusory glass of the photograph and the found Perspex framing it, like buzzing flies.

The presence of the hanging display grid, herding our passage between rooms, intensifies such proprioception – especially when we learn that it came from a business similar to those featured in the photographs, as the Perspex did also: what we’re looking at is all around us. Lomax took the photographs, the starting point of the work for this show, during the Covid-19 pandemic. The businesses they depict are casualties of lockdown, the letters are familiar to most of us, triggering and incriminatory.

![]()

![]()

Lomax tells me that he never intended on making the exhibition about incarceration. He made a concerted decision not to. And yet he did. The prisoners at HMP Grendon baulked in disbelief when he said that redundancy and capitalism were his subjects, not prison life. But, come on… letters? Such a central part of prison life!

Nick London, one of the prisoners at HMP Grendon whom Lomax acquainted, provides one of the accompanying texts. His excavation of the casts – which resemble framed archaeological digs – became a way of reflecting on his own estrangement, folding inwards: “I imagined that if I look hard enough I may see the recipient’s details, and from them I could know more: more of their plight; more of the society to which I must re-join; more of myself.” The artist had initially wondered if the prisoners might remember sodium lamps, but London explains that they are still used in the prison, shining in from outside the cell windows.

![]()

![]()

Does this suggest that Lomax’s residency got to his subconscious? I think Lomax warrants more complex consideration, which means more than the simplistic defence of open-endedness. When I said how flimsy imprisonment can be as a metaphor, I had in mind how it was used – by me and many others – to describe lockdown, more often than not as a gross, insensitive exaggeration. And yet one purpose of metaphor, in keeping with the Greek meaning of word, is to carry across sentiment or meaning, often propelled by disproportion; it is less the word’s indexical correctness than its conveyance of how we feel that matters.

At times, the word “imprisonment” might ring truer to my emotional state than any other at my disposal, regardless of whether my experience is anything in any way like that of an actual prisoner in one of Britain’s prisons. Lomax salvages art’s potential to be such a vessel, which is always and only subjective. With this in mind, we can consider London’s text again, in particular his description of looking at Lomax’s photographs:

“I am a man out of time, installed in a history that was not my own, surrounded by the artefacts of a society to which I did not belong. It’s possible that I’m being myopic, and the reality is that most people would feel the same about this particular moment in history. It could even be that, in those times, I was more a member of this society than I was at any other – all of us, being prisoners, of sorts, back then. Perhaps I am free to select either narrative, and that the freedom itself becomes salient in the choosing to hold multiple versions of reality in a suspended state.”

The prisoner is suspended between two realities, his own and what he imperfectly imagines to be ours, as we – the gallery-goers – are between ours and what we imperfectly imagine to be his. Lomax’s art is where these realities hinge.

![]()

![]()

I go back during daylight and the lights aren’t on. The parallax is disconcerting, not least because the whole scene is now in colour. The reliefs are a dusky pink or teal or beige, extrapolated from the photographs – a shadow’s greenish tinge, a rose on a lonely table. I had said that the concrete was forbidding, and it was when under the oppressive yellow light. But now its capacity for metaphor is ironic: what is concrete is more appreciably illusory, proffering replicas we could mistake for the real thing, all with a sense of lightness.

The rose felt dead before, like a message never received; now it heralds hope, or relief. There are painterly flourishes too: the occasional horizon line, the letters fluttering like quotations of Hokusai. Not that the reliefs weren’t doing any of this before; but Lomax’s work is about perspective – the light in which we see things – which was much altered, or had yet to be altered – depending which way you look at it – the first time around.

![]()

![]()

Lomax is tentative about calling his reliefs paintings, even if, as covetous, rectangular wall pieces, they might as well be. Painting is a loaded concept, suggestive of commerce and embellishment more than any other medium; delimiting, perhaps, for the socially engaged work that Lomax does. For if the reliefs are paintings, or – better put – when they are paintings (it would be disingenuous to say that they are never paintings), their beauty is a restrained one; the concrete, the very painterly defiance of its obduracy, a reminder of what they are besides, of the scuro to their daytime chiaro, the other city.

The letters are and will always be triggering – even when obsolete, they’ll be remembered; even if eventually forgotten, their significance may still be painfully felt, maybe in the same way that Gertrude Stein’s rose is a rose is a rose… accrues and replicates affect as it distances itself from the original flower. If I could ever buy a James Lomax, it would make me happy – while also reminding me of those who could not.

With this in mind, I was inclined to think that his exhibition at Sid Motion also had a form of restricted access, since, aside from the other social and circumstantial restrictions that limit attendance at an art gallery, prisoners would not have been lawfully able to see it. Even on my way to the gallery, I was aware of a serious, non-negotiable division of experience conjured by the image of the prison, an institution I had never stepped foot in.

One thing I can hazard to be sure of is that life in prison is starkly different from life outside it. If all our different experiences of life affect our perspective on it, incarceration exists as a solid – the most solid I can think of right now, along with war – differentiating factor. For me, imprisonment makes more immediate sense as a metaphor: I complain about feeling imprisoned if, for some reason, I don’t sense the freedom to do something I want to do – have a beer with lunch, swim in the sea in winter, improvise an afternoon away from my desk, roaming London’s galleries – even if these are self-imposed restrictions, and thus I am also the person who can lift them. Imprisonment, therefore, actually describes my freedom, if not also my entitlement.

The gallery is one floor up from ground level, divided into three openly interconnected areas, one wall is largely a warehouse window. And yet the atmosphere is stifling, not because of people, but suffusing every square inch of the space is a thick yellow light – the kind of lighting once used to illuminate alleys in Britain’s cities. I recall the sodium hue from police documentaries. It feels like gas, like a substance. It seems to stick to the skin, to everything, and everything is monochrome. The light is like one-point perspective, determining our standpoint, except in a way that pervades our entire frame of vision. I don’t think twice about assuming everything here is grey. People’s eyes are funny, vampire eyes. I am feeling slightly nauseous, attending to everyone around me, mentally, visually, with unusual intensity, as if I am needy of them. I can only think it’s the world closing in on us.

I have to keep reminding myself that the exhibition mainly consists of separate objects, all rectangular and all but one hanging on the walls – reliefs, photographs, and one sourced readymade. The latter hangs from the ceiling as a room divider, made of gridded plastic transparency. Its empty pockets were once used to advertise properties in a now-redundant estate agent’s window, and it still bears the fingerprints of hands changing properties.

The works, individually and as a whole, are experienced spatially, as enclosure. There is something in the way the reliefs – business envelopes strewn on plywood surfaces, except one which consists of an upright rose, all cast in concrete – push back. They forbid and block just as the light blocks their chromatic identity – or us from seeing it. There is something about Lomax’s use of concrete, which under the yellow light seems to work metaphorically, suppressing illusion, forbidding us from making the different components dance with our eyes.

There is also something in the way the photographs of glass doors keep us out, their reflections suggesting a lack of light, or a nothingness, therein. If we see ourselves, or imagine ourselves, reflected in the almost life-size images, we might feel as if trapped between the illusory glass of the photograph and the found Perspex framing it, like buzzing flies.

The presence of the hanging display grid, herding our passage between rooms, intensifies such proprioception – especially when we learn that it came from a business similar to those featured in the photographs, as the Perspex did also: what we’re looking at is all around us. Lomax took the photographs, the starting point of the work for this show, during the Covid-19 pandemic. The businesses they depict are casualties of lockdown, the letters are familiar to most of us, triggering and incriminatory.

Lomax tells me that he never intended on making the exhibition about incarceration. He made a concerted decision not to. And yet he did. The prisoners at HMP Grendon baulked in disbelief when he said that redundancy and capitalism were his subjects, not prison life. But, come on… letters? Such a central part of prison life!

Nick London, one of the prisoners at HMP Grendon whom Lomax acquainted, provides one of the accompanying texts. His excavation of the casts – which resemble framed archaeological digs – became a way of reflecting on his own estrangement, folding inwards: “I imagined that if I look hard enough I may see the recipient’s details, and from them I could know more: more of their plight; more of the society to which I must re-join; more of myself.” The artist had initially wondered if the prisoners might remember sodium lamps, but London explains that they are still used in the prison, shining in from outside the cell windows.

Does this suggest that Lomax’s residency got to his subconscious? I think Lomax warrants more complex consideration, which means more than the simplistic defence of open-endedness. When I said how flimsy imprisonment can be as a metaphor, I had in mind how it was used – by me and many others – to describe lockdown, more often than not as a gross, insensitive exaggeration. And yet one purpose of metaphor, in keeping with the Greek meaning of word, is to carry across sentiment or meaning, often propelled by disproportion; it is less the word’s indexical correctness than its conveyance of how we feel that matters.

At times, the word “imprisonment” might ring truer to my emotional state than any other at my disposal, regardless of whether my experience is anything in any way like that of an actual prisoner in one of Britain’s prisons. Lomax salvages art’s potential to be such a vessel, which is always and only subjective. With this in mind, we can consider London’s text again, in particular his description of looking at Lomax’s photographs:

“I am a man out of time, installed in a history that was not my own, surrounded by the artefacts of a society to which I did not belong. It’s possible that I’m being myopic, and the reality is that most people would feel the same about this particular moment in history. It could even be that, in those times, I was more a member of this society than I was at any other – all of us, being prisoners, of sorts, back then. Perhaps I am free to select either narrative, and that the freedom itself becomes salient in the choosing to hold multiple versions of reality in a suspended state.”

The prisoner is suspended between two realities, his own and what he imperfectly imagines to be ours, as we – the gallery-goers – are between ours and what we imperfectly imagine to be his. Lomax’s art is where these realities hinge.

I go back during daylight and the lights aren’t on. The parallax is disconcerting, not least because the whole scene is now in colour. The reliefs are a dusky pink or teal or beige, extrapolated from the photographs – a shadow’s greenish tinge, a rose on a lonely table. I had said that the concrete was forbidding, and it was when under the oppressive yellow light. But now its capacity for metaphor is ironic: what is concrete is more appreciably illusory, proffering replicas we could mistake for the real thing, all with a sense of lightness.

The rose felt dead before, like a message never received; now it heralds hope, or relief. There are painterly flourishes too: the occasional horizon line, the letters fluttering like quotations of Hokusai. Not that the reliefs weren’t doing any of this before; but Lomax’s work is about perspective – the light in which we see things – which was much altered, or had yet to be altered – depending which way you look at it – the first time around.

Lomax is tentative about calling his reliefs paintings, even if, as covetous, rectangular wall pieces, they might as well be. Painting is a loaded concept, suggestive of commerce and embellishment more than any other medium; delimiting, perhaps, for the socially engaged work that Lomax does. For if the reliefs are paintings, or – better put – when they are paintings (it would be disingenuous to say that they are never paintings), their beauty is a restrained one; the concrete, the very painterly defiance of its obduracy, a reminder of what they are besides, of the scuro to their daytime chiaro, the other city.

The letters are and will always be triggering – even when obsolete, they’ll be remembered; even if eventually forgotten, their significance may still be painfully felt, maybe in the same way that Gertrude Stein’s rose is a rose is a rose… accrues and replicates affect as it distances itself from the original flower. If I could ever buy a James Lomax, it would make me happy – while also reminding me of those who could not.

James Lomax (b. 1991, UK) lives and works in London.

Lomax graduated from the Royal Academy Schools, London in 2022. He has

undertaken residencies at Ikon Gallery, The New Art Gallery Walsall, The Henry

Moore Institute and Studio Block M74 Mexico City. Most recently, he was the

Artist in Residence at HMP Grendon, a Category B men's prison that

operates a unique, psychodynamic therapeutic model.

Lomax's selected exhibitions include: Take a Seat,

LAMB Gallery, London, UK (2024); Chester Contemporary, curated by Ryan

Gander, Chester, UK (2023); Unbound Material, Sid Motion Gallery, London, UK

(2023), Unprecedented Times, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham,

UK (2022), Absurd, OHSH Projects, London, UK (2022), Modern Relics, Fold

Gallery, London, UK (2022), and Flatten & Collapse, Recent Activity,

London, UK (2022).

www.jameslomax.co.uk

Tom Denman is a freelance art critic based in London. His

writing has appeared in Art Journal, The Art Newspaper, ART

PAPERS, ArtReview, Art Monthly, Burlington

Contemporary, e-flux, Flash Art, Ocula,

and Studio International. He holds a PhD in Italian Studies from

the University of Reading, for which he wrote his thesis on Caravaggio and the

noble-intellectual community in seventeenth-century Naples. Now he writes

mainly on contemporary art.

www.tomdenman.info

www.tomdenman.info