Níall

McLaughlin’s Architecture Foundation lecture: from Paul

Klee to Bishop Auckland

London’s Architecture Foundation have been furthering architectural

conversation in London for over 34 years, with regular events including their

Architecture On Stage series presented at the Barbican Centre. Yuki Sumner went

to their most recent talk in which Níall McLaughlin discussed the role buildings

have in giving form to extended time.

If I was seeking enlightenment, the lightbulb moment arrived

not in the crescendo of

Níall

McLaughlin’s 90-minute lecture, but in the

quiet spaces that followed. It came, as these moments often do, in the Q&A

session, when the London-based, Stirling Prize-winning Irish architect quoted

Jorge Luis Borges: “The purpose of art is not to create meaning or to

communicate meaning, but to create a space where meaning can be read”.

In many ways, this was the essence of the evening – an exploration of architecture as a conduit for meaning, a structure through which we might glimpse something larger than ourselves. McLaughlin’s words came in precise, unbroken sentences, each idea slotting into the next. His lecture, Taking Time, wove together philosophy, art, and architecture, urging us to reconsider the way buildings bear the weight of time.

![]()

![]()

![]()

McLaughlin began his talk with an evocative image: Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, a haunting monoprint that has, through the words of Walter Benjamin, come to symbolise history itself. The angel, poised as if about to take flight, is simultaneously held back, trapped by the wreckage of the past, forced forward into the unknown by an inexorable storm.

“The storm is what we call progress,” Benjamin wrote. And yet, McLaughlin left this reference suspended, unexplained, inviting us to consider its presence. Instead, he moved seamlessly into a procession of images, portraits of his teachers from University College Dublin as he paid homage to those who shaped him: Robin Walker, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects, John Tuomey and Sheila O'Donnell of O’Donnell + Tuomey. These were not straightforward acknowledgments; they were part of his thesis. Architecture, he seemed to suggest, is not an individual pursuit, but a palimpsest of inherited wisdom and layered histories.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

McLaughlin’s lecture was divided into two unequal parts: first, a meditation on time and architecture, and second, a more detailed discussion of his studio’s projects. What became clear was that he approaches design not as an engineer of structures but as a storyteller. His work and his words act as study of how architecture embodies the passage of time, a theme he explored with the same painterly sensibility that defines his buildings. McLaughlin’s buildings are deeply rooted in the past, yet they do not mimic history; instead, they reinterpret it, layering new stories onto old foundations.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his response to a client’s unconventional request. The client of Saltmarsh House on the Isle of Wight provided McLaughlin with nothing but images – a wordless brief. Could these images, she asked, be things that would prompt you to design? Among them was a photograph of a Japanese farmhouse, which inspired the concept of raising the structure on a platform. Another showed the woven works of Peter Collingwood, which led to the creation of slender structural supports, so fine they read almost like threads holding up the sky.

Such connections are not mere aesthetic indulgences. They are, McLaughlin argued, essential to the process of architecture. He described lying on the ground in Jaipur’s Amber Fort, sketching the intricacies of an elephant capital that would later inform a crucial design detail. Four centuries collapsed into a single welded corner in the Isle of Wight. “The killer problem,” he remarked wryly, “is always how you turn a corner”.

![]()

![]()

![]()

McLaughlin speaks of buildings as performances. They change with weather, with wear, with the slow accumulation of human presence and interventions. Copper will shift from burnished gold to deep purple, before settling into verdigris. Wood will weather into the same grey as the concrete it meets. These transformations, he suggested, are not signs of decay but of life itself.

Such thinking is evident in his Deal Pier Café, where the wood was chosen not to contrast with concrete but to converge, the passage of time softening the edges between them. This is what McLaughlin refers to as “bagginess” – a quality in architecture that allows space for change, for serendipity, for something beyond the architect’s control. Architecture, in his view, is never static, it’s always part of a larger performance.

![]()

![]()

![]()

McLaughlin’s practice is engaged in a series of projects that feel almost impossibly rich in historical weight. The Faith Museum at Auckland Castle wrestled with the paradox of creating a secular space devoted to religious history. The studio resolved this by referencing skeuomorphism in the shape of the crossing of the rafters from two disconnected human cultures: one as a figure of Christ, the Christian God, found in St McDara’s Chapel on an island off the coast of Galway in Ireland, and another as a symbol of Amaterasu, the Shinto god, at Ise Shrine Complex in Japan, both dating back to 7th century AD. McLaughlin’s reinterpretation delicately surpasses them in profile and execution.

An as yet unbuilt scheme, the Huis van Leyden project in Leiden, will link a 17th-century Baroque palace with a 20th-century Amsterdam School building, binding them together under a crow-stepped gable reinterpreted as a three-dimensional rooftop landscape. Both these projects embody McLaughlin’s fascination with layered time. The past is not something to be preserved in amber but something that must be actively engaged with, reimagined, and, occasionally, argued with. His approach to convincing clients is itself an exercise in storytelling – when an initial design for a welcome building at Auckland Castle was rejected due to it being deemed too similar to the castle itself, McLaughlin returned with a different narrative. He presented a drawing of a siege tower by the 19th-century French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, arguing that the tower should be built in timber, like a temporary structure from an age of medieval warfare. The clients approved. The lesson? Sometimes, the right story unlocks the right solution.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Perhaps the most poetic of McLaughlin’s projects is the chapel at Ripon Theological College. The inspiration was a vision from the Annals of Clonmacnoise in which a ship, navigating the air, drops anchor in a church, the anchor snagging on the altar rail. The resultant design evokes a carousel at the top of the building, a place where light and space turn in slow, sacred rotation. McLaughlin paused at one point to show his favourite image of the chapel – taken at dawn as the first light of day met the last remnants of night. “I love this photo,” he said, “you can see the sun rising in the window on your left, and the night being chased away”.

A similar clarity of vision shaped the International Rugby Experience in Limerick. Inspired by the mechanics of a rugby scrum – “an arch made by 16 people” – the building embodies strength through cohesion, its precisely arranged brickwork mirroring the physical interdependence of players, creating a structure that is both steadfast and kinetic. Though monumental in scale, it remains finely tuned—every brick and joint interlocking with intent, producing an architectural cadence that feels deliberate and civic yet also very much animated.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

At the end of the evening, as the audience trickled out into the cold, I found myself returning to Borges’ words. McLaughlin’s buildings do not dictate meaning but create the conditions for meaning to emerge. His work stands not as a monolith but as a space of invitation – an architecture not just of form, but of possibility.

And so, we are left, like Klee’s Angelus Novus, suspended between past and future, caught in the storm that is progress, and yet – just for a moment – able to see it all, an invitation to think of architecture not as a fixed object but as an ongoing story.

In many ways, this was the essence of the evening – an exploration of architecture as a conduit for meaning, a structure through which we might glimpse something larger than ourselves. McLaughlin’s words came in precise, unbroken sentences, each idea slotting into the next. His lecture, Taking Time, wove together philosophy, art, and architecture, urging us to reconsider the way buildings bear the weight of time.

figs.i-ii

McLaughlin began his talk with an evocative image: Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, a haunting monoprint that has, through the words of Walter Benjamin, come to symbolise history itself. The angel, poised as if about to take flight, is simultaneously held back, trapped by the wreckage of the past, forced forward into the unknown by an inexorable storm.

“The storm is what we call progress,” Benjamin wrote. And yet, McLaughlin left this reference suspended, unexplained, inviting us to consider its presence. Instead, he moved seamlessly into a procession of images, portraits of his teachers from University College Dublin as he paid homage to those who shaped him: Robin Walker, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects, John Tuomey and Sheila O'Donnell of O’Donnell + Tuomey. These were not straightforward acknowledgments; they were part of his thesis. Architecture, he seemed to suggest, is not an individual pursuit, but a palimpsest of inherited wisdom and layered histories.

figs.iii-vi

McLaughlin’s lecture was divided into two unequal parts: first, a meditation on time and architecture, and second, a more detailed discussion of his studio’s projects. What became clear was that he approaches design not as an engineer of structures but as a storyteller. His work and his words act as study of how architecture embodies the passage of time, a theme he explored with the same painterly sensibility that defines his buildings. McLaughlin’s buildings are deeply rooted in the past, yet they do not mimic history; instead, they reinterpret it, layering new stories onto old foundations.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his response to a client’s unconventional request. The client of Saltmarsh House on the Isle of Wight provided McLaughlin with nothing but images – a wordless brief. Could these images, she asked, be things that would prompt you to design? Among them was a photograph of a Japanese farmhouse, which inspired the concept of raising the structure on a platform. Another showed the woven works of Peter Collingwood, which led to the creation of slender structural supports, so fine they read almost like threads holding up the sky.

Such connections are not mere aesthetic indulgences. They are, McLaughlin argued, essential to the process of architecture. He described lying on the ground in Jaipur’s Amber Fort, sketching the intricacies of an elephant capital that would later inform a crucial design detail. Four centuries collapsed into a single welded corner in the Isle of Wight. “The killer problem,” he remarked wryly, “is always how you turn a corner”.

figs.vii-ix

McLaughlin speaks of buildings as performances. They change with weather, with wear, with the slow accumulation of human presence and interventions. Copper will shift from burnished gold to deep purple, before settling into verdigris. Wood will weather into the same grey as the concrete it meets. These transformations, he suggested, are not signs of decay but of life itself.

Such thinking is evident in his Deal Pier Café, where the wood was chosen not to contrast with concrete but to converge, the passage of time softening the edges between them. This is what McLaughlin refers to as “bagginess” – a quality in architecture that allows space for change, for serendipity, for something beyond the architect’s control. Architecture, in his view, is never static, it’s always part of a larger performance.

figs.x-xii

McLaughlin’s practice is engaged in a series of projects that feel almost impossibly rich in historical weight. The Faith Museum at Auckland Castle wrestled with the paradox of creating a secular space devoted to religious history. The studio resolved this by referencing skeuomorphism in the shape of the crossing of the rafters from two disconnected human cultures: one as a figure of Christ, the Christian God, found in St McDara’s Chapel on an island off the coast of Galway in Ireland, and another as a symbol of Amaterasu, the Shinto god, at Ise Shrine Complex in Japan, both dating back to 7th century AD. McLaughlin’s reinterpretation delicately surpasses them in profile and execution.

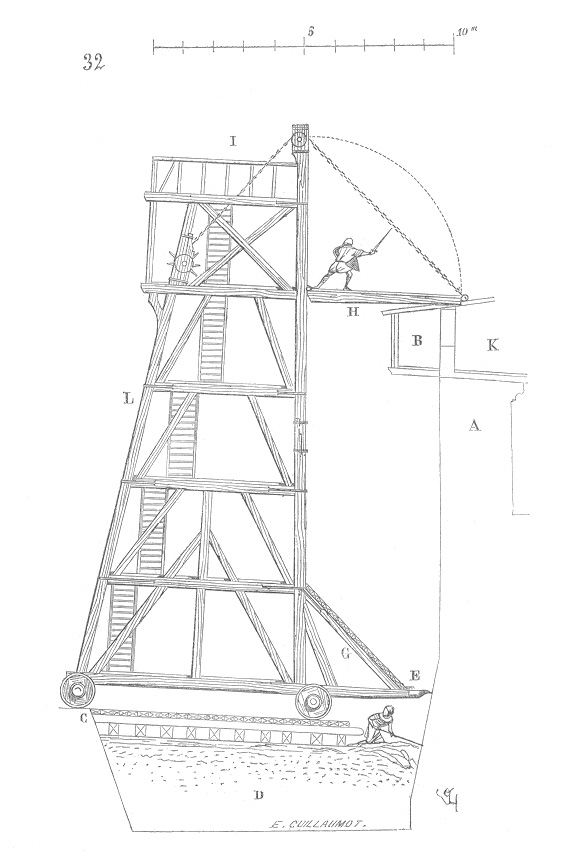

An as yet unbuilt scheme, the Huis van Leyden project in Leiden, will link a 17th-century Baroque palace with a 20th-century Amsterdam School building, binding them together under a crow-stepped gable reinterpreted as a three-dimensional rooftop landscape. Both these projects embody McLaughlin’s fascination with layered time. The past is not something to be preserved in amber but something that must be actively engaged with, reimagined, and, occasionally, argued with. His approach to convincing clients is itself an exercise in storytelling – when an initial design for a welcome building at Auckland Castle was rejected due to it being deemed too similar to the castle itself, McLaughlin returned with a different narrative. He presented a drawing of a siege tower by the 19th-century French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, arguing that the tower should be built in timber, like a temporary structure from an age of medieval warfare. The clients approved. The lesson? Sometimes, the right story unlocks the right solution.

figs.xiii-xvi

Perhaps the most poetic of McLaughlin’s projects is the chapel at Ripon Theological College. The inspiration was a vision from the Annals of Clonmacnoise in which a ship, navigating the air, drops anchor in a church, the anchor snagging on the altar rail. The resultant design evokes a carousel at the top of the building, a place where light and space turn in slow, sacred rotation. McLaughlin paused at one point to show his favourite image of the chapel – taken at dawn as the first light of day met the last remnants of night. “I love this photo,” he said, “you can see the sun rising in the window on your left, and the night being chased away”.

A similar clarity of vision shaped the International Rugby Experience in Limerick. Inspired by the mechanics of a rugby scrum – “an arch made by 16 people” – the building embodies strength through cohesion, its precisely arranged brickwork mirroring the physical interdependence of players, creating a structure that is both steadfast and kinetic. Though monumental in scale, it remains finely tuned—every brick and joint interlocking with intent, producing an architectural cadence that feels deliberate and civic yet also very much animated.

figs.xvii-xx

At the end of the evening, as the audience trickled out into the cold, I found myself returning to Borges’ words. McLaughlin’s buildings do not dictate meaning but create the conditions for meaning to emerge. His work stands not as a monolith but as a space of invitation – an architecture not just of form, but of possibility.

And so, we are left, like Klee’s Angelus Novus, suspended between past and future, caught in the storm that is progress, and yet – just for a moment – able to see it all, an invitation to think of architecture not as a fixed object but as an ongoing story.

Níall McLaughlin was born in Geneva in 1962. He was educated in Dublin & studied architecture at University College Dublin between 1979 & 1984. He worked for Scott Tallon Walker for four years & established his own practice in London in 1990. He designs buildings for education, culture, health, religious worship & housing. He won Young British Architect of the Year in 1998 & received the RIBA Charles Jencks Award for Simultaneous Contribution to Theory & Practice in 2016. Níall was elected an Aosdána Member for Outstanding Contribution to the Arts in Ireland & as a Royal Academician in the Category of Architecture in 2019. In 2020 he was awarded an Honorary MBE for Services to Architecture & has been shortlisted for the RIBA Stirling Prize in 2013, 2015 & 2018 winning the Stirling Prize in 2022 for the New Library, Magdalene College.

Níall exhibited in the Venice Biennale in 2016 & 2018, co-curated the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition Architecture Rooms in 2022 with Rana Begum. Níall is Professor of Architectural Practice at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London. He was a visiting professor at the University of California Los Angeles from 2012-2013 & was appointed Lord Norman Foster Visiting Professor of Architecture at Yale for 2014-2015.

www.niallmclaughlin.com

The Architecture Foundation leads the conversation on the development of London & contributes to a global discourse about the architect’s changing role & responsibilities. They pursue this mission through the delivery of an accessible public programme that makes space for emerging architects, groups historically underrepresented in the profession & representatives of a wide range of related disciplines. Exploring the architect’s capacity to combat climate change & systemic social inequalities represent central concerns of the programme.

www.architecturefoundation.org.uk

Yuki Sumner is a London-based writer & researcher

specialising in art, architecture & design. With over 20 years of experience

contributing to international publications, she offers a critical & insightful perspective on contemporary design & the built environment. In

2023, she curated a show called Future is Rural at London Design Biennale & formed a collective dedicated to promoting artists& designers engaged in

revitalising rural communities. She is currently developing an interactive map

to further explore the intersection of contemporary art, design & rural

landscapes. Yuki is a trustee board member of Invisible Dust.

www.yukisumner.com

www.architecturefoundation.org.uk

Yuki Sumner is a London-based writer & researcher

specialising in art, architecture & design. With over 20 years of experience

contributing to international publications, she offers a critical & insightful perspective on contemporary design & the built environment. In

2023, she curated a show called Future is Rural at London Design Biennale & formed a collective dedicated to promoting artists& designers engaged in

revitalising rural communities. She is currently developing an interactive map

to further explore the intersection of contemporary art, design & rural

landscapes. Yuki is a trustee board member of Invisible Dust.

www.yukisumner.com

more information

Níall McLaughlin’s lecture took place on Sunday 09 March as part of Architecture

on Stage, a programme of talks curated by the Architecture Foundation in

partnership with the Barbican Centre.

To find out about future Architecture Foundation events, visit their website at: www.architecturefoundation.org.uk/events

The

second edition of Níall McLaughlin Architects’ publication 12 Halls has just been published.

The new edition can be purchased here:

www.objectif.co.uk/en/edition/twelve-halls

images

fig.i

Níall McLaughlin presenting his lecture at the Barbican Centre. Photograph courtesy Bryony Jones, Tom McGlynn & Níall McLaughlin Architects.

fig.ii Paul Klee, Angelus Novus (1920). Photograph© Christian Mantey. Work reproduced under Public Domain.

fig.iii Saltmarsh House by Níall McLaughlin Architects. Photograph

© Nik Eagland.

fig.iv Peter Collingwood artwork. Photogrpah © Tom Grotta, courtesy of browngrotta arts.

figs.v,vii

Saltmarsh House by Níall McLaughlin Architects. Photograph © Nick Kane.

fig.vi Column decoration in the Amber Fort, Jaipur. Photograph © David Brossard, reproduced under Creative Commons. Image available here.

figs.viii-x Deal Pier Cafe. Images courtesy Níall McLaughlin Architects.

fig.xi Auckland Castle Faith Museum. Photograph © Nick Kane.

figs.xii,xiii

Auckland Castle Faith Museum. Photographs © David Valinksy.

fig.xiv Aukland Tower. Photograph © Nick Kane.

fig.xv A medieval siege tower, drawing by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

figs.xvi,xvii

Aukland Tower. Photographs © Richard Chivers.

figs.xviii,xix Bishop Edward King Chapel at Ripon Theological College. Photographs courtesy Níall McLaughlin Architects.

figs.xx,xxi The International Rugby Experience in Limerick. Photographs © Nick Kane.

publication date

26 March 2025

tags

Architecture Foundation, The Amber Fort, Aukland Castle, Barbican Centre, Walter Benjamin, Jorge Luis Borges, Peter Collingwood, Deal Pier Café, The Faith Museum, Huis van Leyden, The International Rugby Experience, Paul Klee, Niall McLaughlin, Niall McLaughlin Architects, Ripon Theological College, Saltmarsh House, St McDara’s Chapel, Yuki Sumner, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

To find out about future Architecture Foundation events, visit their website at: www.architecturefoundation.org.uk/events

The second edition of Níall McLaughlin Architects’ publication 12 Halls has just been published. The new edition can be purchased here: www.objectif.co.uk/en/edition/twelve-halls