An interview with Peter Cook about Archigram, drawing & building

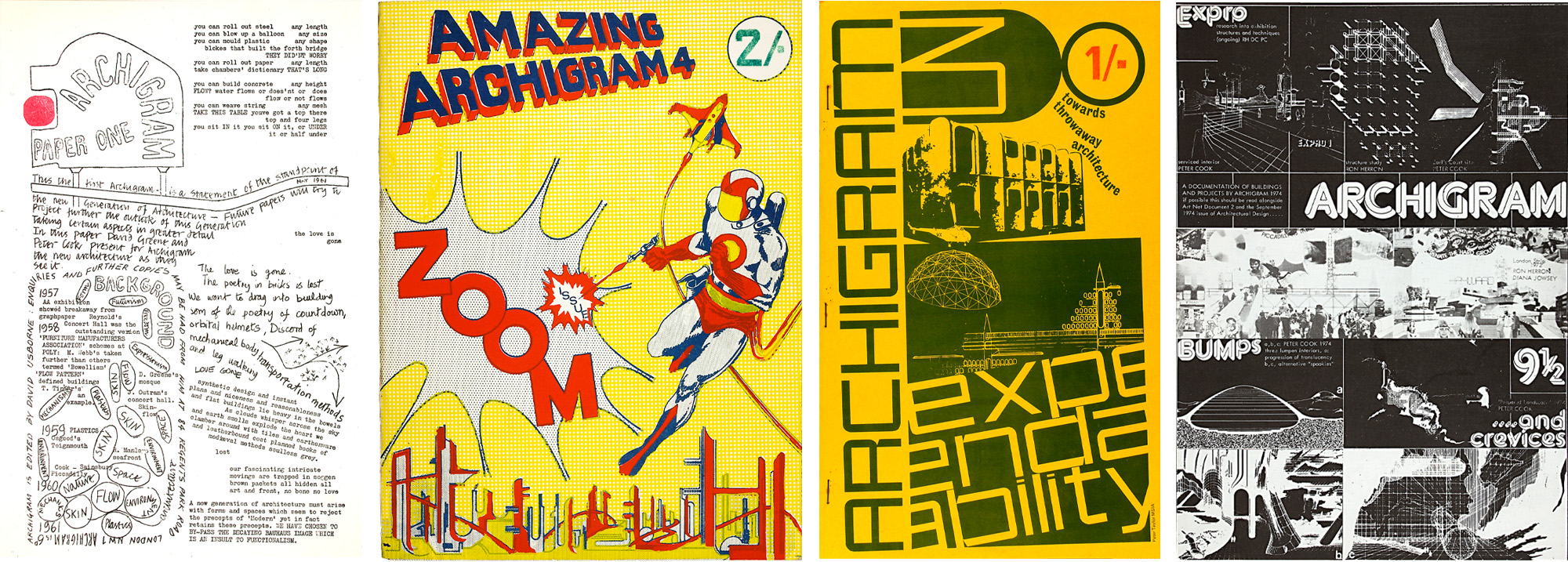

A few months ago for our reader-supported newsletter A Deeper Recess, to mark the publication of Archigram 10, a book published by Circa Books & edited by Peter Cook, we sat down with the founder of Archigram to talk about his approach to drawing & designing.

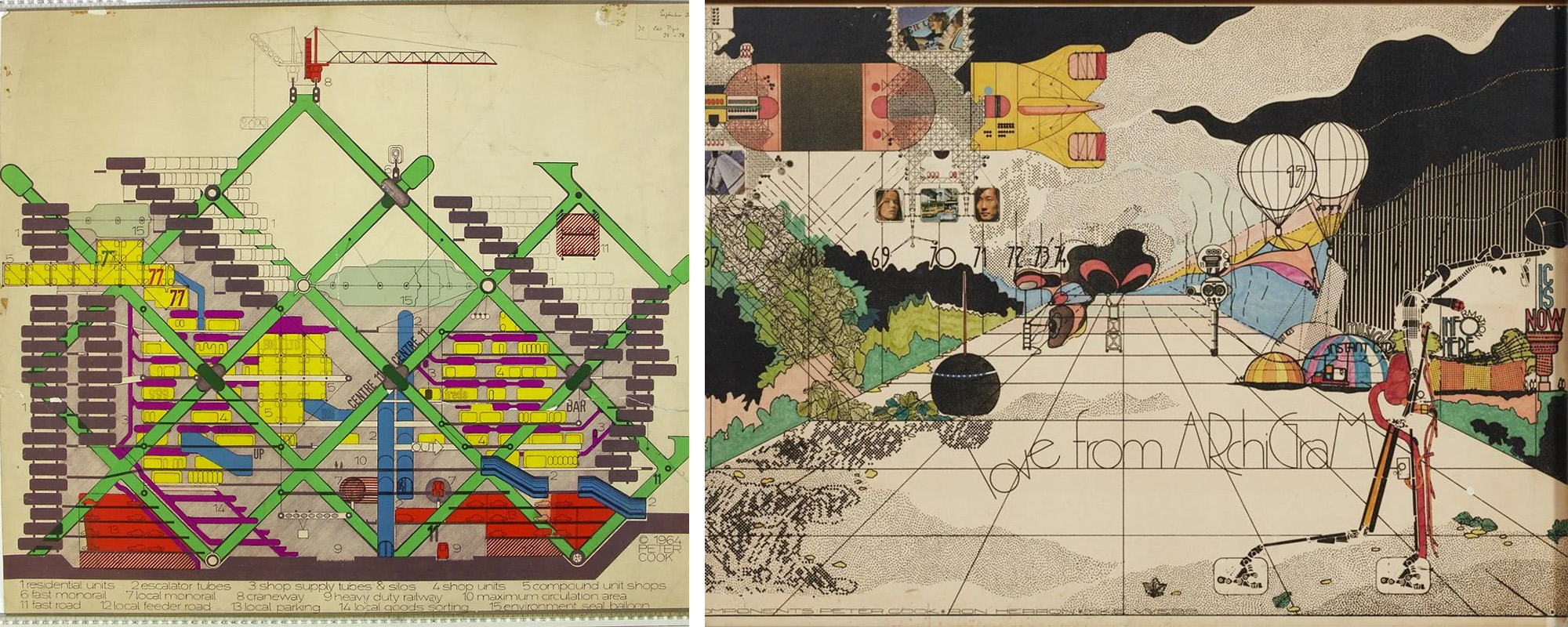

Peter Cook, an architect who, despite only designed a handful of buildings around the world, has impacted the post-war period of architect more than most others. As a founding member of Archigram, the avant-garde architecture group which ran from 1960 until the mid 70s, he was involved with speculative ideas for the future of the built environment which went beyond the mundanity of everyday design and reached into playful, utopian futures where cities could walk, were networked across wide terrains, where buildings were adaptable frameworks, or cities were transformed in radical ways which spoke to a futurist ambition as a provocative reaction to the pre-war period.

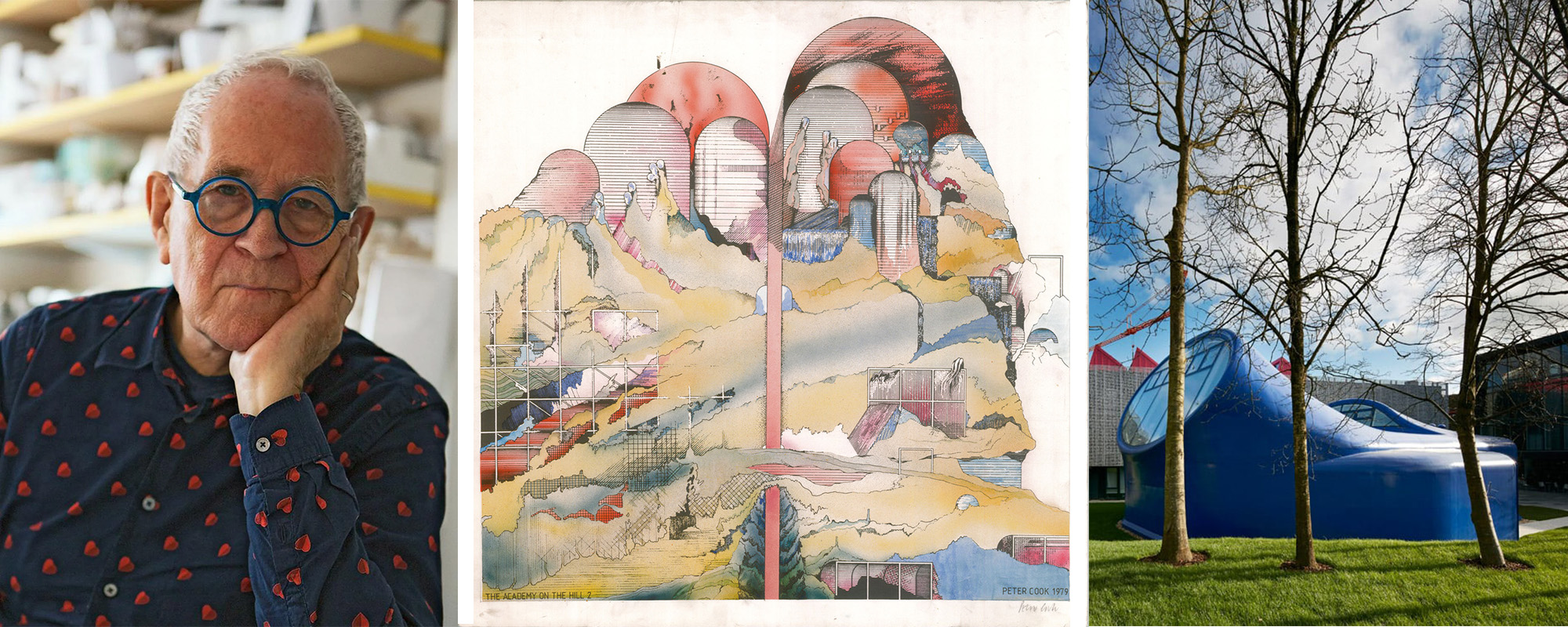

Archigram existed as magazines not buildings, with publishing central to the way architectural exploration could exist at the drawing stage, with the drawing as the central and probable final mechanism to explore design ideas. Cook’s designs have moved beyond the drawing – his first project, designed with fellow Archigram member Colin Fournier, was the spaceship-like Kunsthaus Graz in Austria, and other commissions have followed, including a boutique Drawing Studio at the University of the Arts in Bournemouth, a return to where the architect started his architectural training in 1953. He has also been involved with designs related to the controversial NEOM projects in Saudi Arabia, including The Line, which are part of the state’s Saudi Vision 30 ambitions which ITV recently reported as having led to 21,000 deaths of workers since 2017 and which the Hindustan Times claim has led to 100,000 people “disappearing” during construction.

Kunsthaus Graz, the Drawing Studio, and The Line are brought up by Cook in this discussion, though the focus centres on the role of drawing in architectural design. Another project alluded to, but which couldn’t then be named, is the Play Pavilion Cook designed for the Serpentine Gallery (more info HERE), a project incorporating Lego.

Circa Press have just released Archigram 10, a slick and modern publication continuing the series – albeit with a gap of 51 years since Archigram 9½ – that was overseen by Cook. The discussion begins by asking about the role of drawing in design – though the architect often heads into other places, including towards the end sharing his thoughts on why buildings made of wood irritate him and how architectural education has declined because of feminism…

This interview was originally published on A Deeper Recess, the reader-supported newsletter from recessed.space that runs parallel to the free news update bulleting, The Recess, delivered straight to your inbox. Please consider subscribing to A Deeper Recess to help support independent writing on art and architecture, more details available HERE.

figs.i-iii

I am interested in the intersection of the drawing process and use of drawing within design of buildings – and through that, the benefits and flaws with the inherent imperfections of drawing compared to realistic CGI renders we're increasingly used to. Before we get there, tell me first about your personal approach to drawing.

Well, I grew up drawing in ink and then colouring. Now, I’m involved in various competitions that are paid for, but rarely do they emerge as a building – occasionally they do, as you know, but the drawing is the motivation. In fact, I even wrote a book some time ago called Drawing: The Motive Force of Architecture – the title was chosen by my publisher, but it's quite appropriate, and as I always say, I was never really a good drawer at school.

Art wasn't your favourite lesson? Or were you just not very good at it?

I had an extremely good grammar school with an extremely good art master who was well informed about architecture and my mother took me to galleries when I was young, but technically I wasn't good at reproducing trees, dogs, bowls of fruit, and spaces. I travelled – my dad was an army officer so I went to many different schools, and I don't blame the teachers – but I was someone who couldn’t accurately reproduce things.

Even when I joined architecture school at Bournemouth College of Art there were people who could draw much better than I. We had some good teachers who improved me, and I think I've learned by being alongside a lot of people who can draw very well – a succession of close associates like Ron Heron, David Green, then later Christine Hawley and Gavin Robotham, all people who have sat alongside me, metaphorically, and who can really draw! It's been artisanship, if you like, that I have been alongside people who did it better and learnt various tricks of the trade – I still use French curves and straight edges, tricks to make the drawings not so embarrassing.

Does it matter? What is an embarrassing drawing?

I suppose I've developed. I now sell drawings in art galleries and I think some graphics that I make can be very effective. I wouldn't say it's dependent upon the drawing, because it's basically architectural drawing.

figs.iv,v

So, are the drawings read differently by different audiences? You’ve recently shown work at Richard Saltoun gallery in London and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen, do these audiences read the drawings differently to architects? If it’s on the wall, in a frame, does it make it a work of art and not an architectural drawing?

I think people don’t always read them for the reasons I intend. I'm involved in a book at the moment, it will be 15 or 16 drawings plus one building. It’s a book not with lots of drawings, but with analysis of particular drawings where they come from, what influenced me, what other drawings, buildings are referred to, things from my childhood, lumps and hates and fears. It talks around a drawing much more than the usual book which might have a paragraph or an essay, it goes in depth into drawings.

Usually I need a little bit of distance between the drawing and publishing. I don't mind showing drawings in lectures, then publishing a year or so later, when it's settled where it sits in respect of the work. Meanwhile, there are drawings I'm doing which… there’s something on the table here, which I'm not allowed to tell you what it is, though it will be made public soon and it has moved very quickly into construction drawings. As soon we win a competition, I’m so busy getting the bloody thing done that I don't get to do my funny drawings!

This is when your drawing moves elsewhere in the office, towards the detailing stage. So your drawings are many things – design process, decorative, art objects – and they all have different lives?

With the Archigram 10 magazine, I didn't create the graphics but they're very particular, very insistent graphics. I have got some drawings in the magazine, if you know where to look, but they're subsumed into the general mode. I'm used to being the victim of graphic designers laying out books – sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't. My own personal preference in a straight book is to just leave the material fairly well alone with readable text and have a good index at the back – I'm quite prosaic in that respect, I want people to know about what I'm doing. And I think that when I write, which I’ve always been able to do very easily, I write like a journalist.

fig.vi

A journalist, but not critic, though? Because at the launch of Archigram 10 you said that critics are “crabby”. What does that word mean to you and why are English critics particularly “crabby”? As an art and architecture critic, I promise not to take it personally!

It means mealy-mouthed, grudging, and Puritan. To cite another architect, I always felt Zaha Hadid was grudgingly treated by the British press.

Racism and misogyny might have had something to do with this too, especially in that period?

Maybe, but I think they also were irritated by her talent and her larger-than-life persona. I haven’t considered misogyny, because she never considered herself a woman architect.

Zaha Hadid was an architect who was also an incredible artist, separate to their architectural work, but also interestingly interconnected with the architecture. I think her paintings stand visually as artworks, but also with my architecture hat on I can see how incredibly rich they are in relation to built and unbuilt architecture.

There’s a strong tradition of places where drawing is important. My own wife, who's an Israeli, came to the Architectural Association having studied in her own country and she said, “My God, everybody draws so well, we draw with our feet in Israel!” You could say there are certain countries where drawing is part of the game – Austria at a certain period, certainly Japan. There are places where drawing is exquisite, almost irrespective of the talent of the people – places from where you get a nice drawing even if the building or project is mediocre, they just can't not draw well! And then there are other countries where somebody may just do a sort of sketch, then somebody goes and builds it, which can be quite shocking in some respects.

Then there's the relationship between the drawing to be built from and the initial drawing. Prior to this project I cannot discuss, I made about six versions very quickly using coloured pencils, very quickly. Then over a series of meetings, the design arrived at this idea, but then the drawing is taken out of my hands to people in the office who stick it on the computer and manipulate it. I sometimes feel, not that I've lost control of it, but that I’ve lost the graphic control of it.

Do they feel like two separate projects now, the project in your sketch and the one that enters the computer? Or are the drawings contiguous?

Well, there are other projects, like a lot of in the Middle East to do with NEOM, all for competitions. They sort of disappear, and then sometimes the client comes back again and insists upon computer generated visualisations to a very high resolution. I feel they get lost very quickly, because I don't personally always like what the what the computer visualiser does to a project, it gets very kind of schmaltzy very quickly.

I wanted to ask about that. Recently I looked through all the entries for the Helsinki Architecture and Design Museum, which anybody could enter, unnamed. An entry could be a Part 1 Architecture student or a world-famous architect, and because all of the images were so richly rendered, fantastical, and appearing as a built or buildable project, everything was flattened in a bad way. Because the finished building would never really look like any of renders present, but a drawn sketch, especially at that early design stage, might carry so much more meaning.

The largest competition I was ever involved in as a judge, 15 to 20 years ago, was the Grand Egyptian Museum. It was an involved judging process with 1500 entries – a giant number – and two one-week sessions of first judging, to simply get it down to, I think, 20 projects. It wasn’t actually that difficult, we were a very mixed jury, we weren't all peas-in-a-pod, but it was very well organised, disciplined, and un-fixed. It was anonymised until the envelope was opened after the second round and a lot of famous people were eliminated without us knowing. I think Zaha got eliminated in the first round, maybe because the scheme just wasn't that good, or maybe it looked like somebody imitating Zaha! This sometimes happens – when I and Colin Fournier won a big competition for the Kunsthaus Graz, the judges thought it was from our students – and they were slightly relieved when it was us!

In Giza, the winners were Heneghan Peng Architects and the drawings were impeccable. The mannerism had a strangely Norman Foster-esque aspect, we thought it could have been Foster, but no, it was Heneghan Peng – but nobody had heard of them.

figs.vii,viii

Heneghan Peng were a young firm then. In the time that the Grand Egyptian Museum has taken to get to where it is now, and it’s still under construction, they have seen many projects completed. It is interesting that they were then unknown – do you think there is a problem in the brand recognition of certain architects, and how now it can be copied and replicated so easily with computer renders?

Everybody seems to design the same sort of stuff. But mannerisms can also come through visualisations. I think there are some amazing drawings that have been made on a computer – I think it's still about who's in control of it, but I have a particular distaste of renderings. I don't care if plans, sections, and informational drawings are made with whatever method is appropriate – photographic, computation, it can even be AI – but I dislike renderings where the view of the place is homogenised into something that will be popular.

I have one drawing I’m putting in this book called Sinister Street. It's the only drawing I've done where I'm almost stage designing in my head. It's not the most interesting architectural drawing, but it's my one attempt to do something atmospheric, and more than atmospheric – sinister. How do you draw sinister? I can't draw sinister, because my drawings tend to be cheerful, but in this one I am trying to.

I think that the notion of a sinister street runs back to my childhood. I had to move towns, by the time I was about eight or nine I could use the bus, and it was safe for a kid to walk anywhere. I would arrive in a new town and would know that in a typical British town the wind comes from the west, therefore Nob Hill is on the west, the poor people are down to the East, and then there's gasworks, a bridge over the river, a castle, a railway station, then near the railway station would be a certain sort of atmosphere, and down certain sorts of streets it would be a bit scary – you don't go down there. Other areas are more posh and quite pleasant, nice people walking dogs. It was part of one’s British provincial culture, and then when you get much older and you visit, even foreign cities – which can be more scary – the sinister street is the sinister street, and you think, “I won’t go down there!”

Sometimes computer renders can be accidentally sinister, with their render ghost images of people in a scene repeating in different places, or the Disney way everything is trying to look perfect, and through that uncanny perfection a feeling that everything must be wrong in this idealised world.

That's interesting. I've seen student drawings where there's something that makes you feel uncomfortable. I don't think this drawing I made of Sinister Street is uncomfortable enough. I'm still interested in the issue, and maybe the drawing opens a whole series of observations of the city, like the conversation we're having now. In this book, in talking about the drawing I might include pieces of the drawing, referencing other things, towns I know, funny people, funny people with wooden legs, dogs going down drains – just the whole thing about what a city is, which I think is about observation.

I find a lot of my drawings use the title “City”, because cities are evocative. Something my wife noticed is that I always use a title, that I'm very interested in the title – I decide on the title before the end of the project, and usually it's a snappy title.

figs.ix,x

And was that always the case with Archigram projects, which have such snappy titles, many of which have stuck into the consciousness?

Yes, it helps tell you what you have to do – if you’re somewhere through the drawing, then you realise it’s not going the right way and you wonder if you have lost the plot, the title is useful. Some titles can gestate – if I go back as far as The Plug-In City, it gestated, it had various versions and editions over about four years. And the idea of Arcadia also was an earlier thing, and it’s returned much more recently. It revolves, sometimes prompted by a competition cropping up that revives an interest in an idea. You don't forget ideas.

There's a housing competition entry ongoing in the office. I've only previously built two bits of housing, but as a student my generation was very trained up on LCC housing regulations. My first big job after graduating was a big housing scheme, it didn't get built but it was a big piece of research on housing. So, now the office is doing a housing competition it all comes back, like click! – I know three places to put the bathroom, I recall the escape runs, or how to use balconies, and making sure the person washing gets a good view – it’s all sitting there in the memory.

I presume also that there are other architects’ projects which, ones that even if you’re not referencing or quoting, inspire you?

I get depressed by many of them, mostly the English ones… I am a member of the RIBA, so I get the RIBA Journal, but it's all so worthy! The winners of the MacEwen Award [recognising architecture for the common good] all make Do Goody stuff in wood. I mean, it's fine, but what is there to look at?

So where do ethics come into architecture for you, or where do they enter the design process?

Ethics? Not much. I think I have common sense, which is different from ethics. I think it's great if the person doing the washing up gets a good view, I think it's good if you can make the staircase safe and well lit, I think it's quite useful if you can use double height space in multifarious ways, if you consider storage under the bed. But all this Do Goody stuff in wood is a particular irritation.

But it’s not just the wood for aesthetic – we are in the Anthropocene and I think everybody acknowledges architecture is a major contributor to the environmental crisis, whether through existing buildings’ energy use or new construction.

I'm not against wood… if I take architects like Helen and Hard in Norway, they do amazing things with wood, but something about it just irritates me – it’s like meeting a bore on a railway train.

So, if you don’t get architectural inspiration from flicking through magazines, do you draw inspiration looking at art? You talked about how your mother took you to galleries as a child.

I have had problems with art. When I was a professor in Germany [at Frankfurt’s Städelschule Fine Arts Academy] it was quite a famous art school where very important artists taught. They had a system where all the professors had to take part in choosing the students who would join the following year. Therefore, I was adjudicating on a panel considering painters, and art professors would like to sit in on some of our architecture juries. Some of the most brilliant artists were the most narrow-minded when it came to architecture.

When I got a new job at The Bartlett School of Architecture [in London] we needed to find my successor. Daniel Libeskind applied, but the artists blocked him because they thought he was too arty, that he would be a threat. And then I have found at the Royal Academy, where I am a member, there are some nice people, but we don't have a lot in common if I'm honest.

I think there are a lot of differences in the thinking between artists and architects, I think artists are much more wilful in their relationship of art to anything else. I mean, however much I'm a left-field – or whatever, right-field, fun, a bit of an eccentric – character by general architecture standards, I'm still very cognisant of what people will do with the finished drawing, how they will use it, how they will have a contemplative drawing.

figs.xi-xiii

So it goes back to idea of the drawing as a diagram, instruction, or process?

Architects are always open to criticism, always open to scrutiny, always open to operation. Architects have to work through other people. I can't remotely draw anything I like – even little drawings go through a process.

So if you're having an exhibition at Richard Saltoun Gallery, Louisiana Museum, or publishing a book of drawings, are these drawings now art rather than architecture? I'm trying to find that gap between the art object and the architectural diagram.

It’s a little bit irritating now that more people are interested in my drawings than the actual ideas, which is why I'm keen to do this book about the ideas – which I think will become more about architecture than drawing.

I would say that many artists I've interviewed have a similar complaint, that their art object gets passed around the public or media purely as an aesthetic, when they are mostly interested in their own work with deep and conceptual meanings.

My drawing doesn’t come from nowhere. And it’s not interested in being abstract. It tends to be figurative, in the sense that there's a thing in the corner there. It's a funny old thing, but it is there, and it would be about so high.

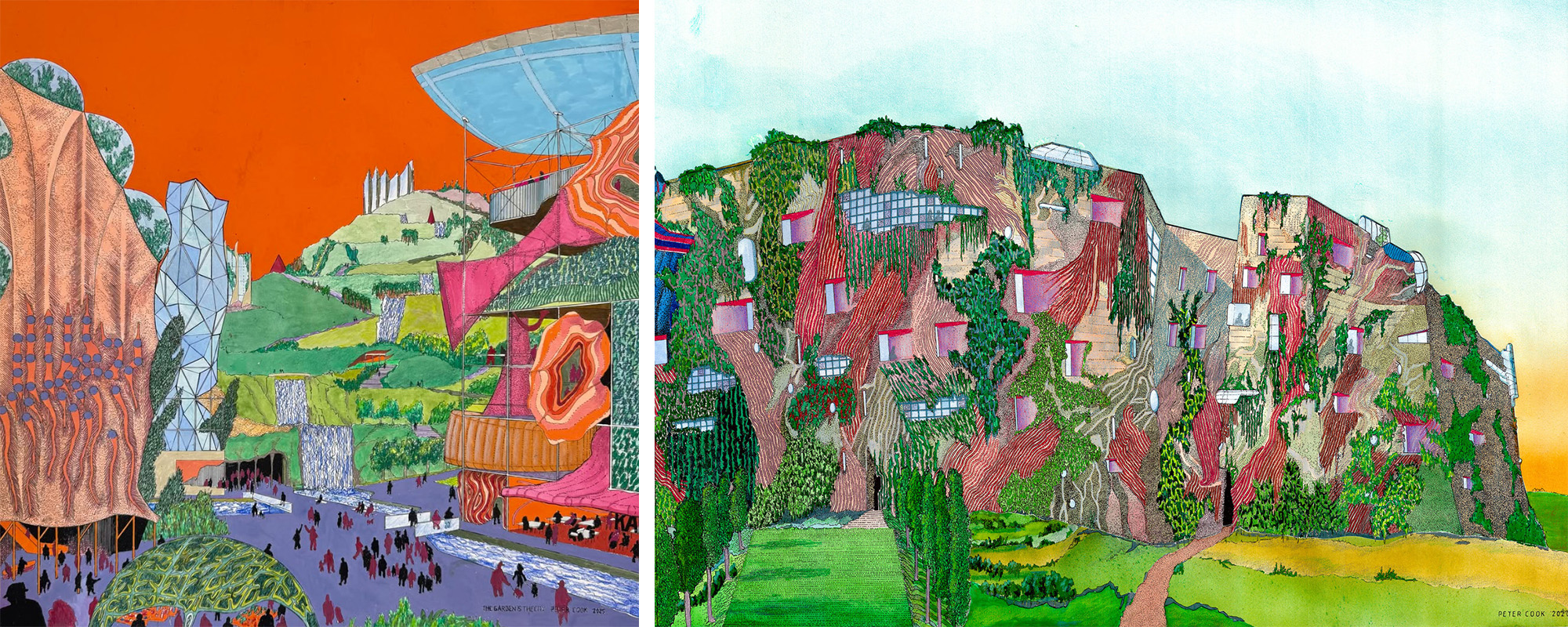

figs.xiv,xv

So you always draw with a sense of scale, idea, proportion, and meaning?

Yes. I did one drawing recently called The Garden is the City, a garden descending into this piece of landscape. There's a picture in my mind of a street in Bilbao where you get a view of the Guggenheim at the end, and behind it is a hill. It's very strong that because you get this extraordinary object in a normal street. Years ago, my son's school asked various parents to talk about what they did, so I did a presentation and showed the Guggenheim. A little girl put her hand up, and said “is there a sheep in the distance?” She was right, there was. And it's always fascinated me – the view and the remark about the sheep.

And her ability to look through the image? Which is what you're trying to do in the book you’re planning now, trying to go through the drawing and find details within it, not just the literal meaning.

Yes, in a way it's post-rationalisation, but I think it digs up all sorts of things. And in the book, alongside the drawings I have chosen one building – a little blue building, the Drawing Studio at the Arts University Bournemouth.

Earlier you said that when at the university you considered yourself not the best at drawing, so was the Drawing Studio design seeking the ideal place for drawing in terms of light and space, the optimum conditions for the students there today to become better at drawing than you could?

There's a certain irony in that, but it's also true that I can argue the building – there’s a north light, it has a boosted clerestory light at the back, a toilet in the corner, a porte-cochère … but, there are other qualities, like giving a giving a hint of the presence of people by revealing the floor so you might see feet but you can't see the person, or tilting the north light so people inside can't see people outside, but can see the pine trees, which are very symbolic of the town.

figs.xvi-xviii

Are these qualities you find useful for the drawing process? To be slightly withdrawn, but also aware of what is beyond?

I think that if you just had a sort of totally abstracted space, if you just saw the sky, you could be anywhere, and if you could see the people drawing, that would blow it! And there’s also the idea of a total blue on the outside and a total white on the inside – to do that it was an expensive building, it had a wonderful budget. To get that degree of purity, you have to spend money – but they've got their money's worth because they use it relentlessly and any time they're mentioned, there’s a photograph of it! We also designed a second, cheaper building there. It was twice the size and half the price – you get what you pay for.

So, to pull all this together, thinking about drawings – you have these books of drawings coming soon, and you've got Archigram 10 just published, which is not all drawings by you, but I would say follows the aesthetic sensibilities of Archigram?

The motive there was really to revive the notion of gathering interesting people together. I have a hobby horse topic at the moment, which is that architecture schools are so scared. They're not putting anything out there, unless you have a wooden leg or are a feminist. Particularly the Bartlett School of Architecture, I think the Bartlett still has some amazing teachers, but as an institution, it seems it hasn't come out of a cloud.

You mean the cloud of the last few years, the allegations of sexism and racism? [note: UCL Bartlett School of Architecture later apologised for the “boys club” atmosphere and a “culture of bullying” after an external report claimed a “toxic culture spanning decades,” leading to the suspension of a number of members of staff.]

Apparently, most of those people have been cleared, but if you look up Wikipedia, there's no sign of that. I know most of those people, and I've met them since.

So you think that the Bartlett School of Architecture is still impacted by that cloud? Because it's still one of the leading places in the country for honing drawing skills, aesthetics, and technical abilities.

I know that everybody there seems to be a bit, sort of, scared.

So Archigram 10 was developed to try to find a form of group-thinking and publishing free from those pressures?

It’s group-thinking because the combination of people can be blamed exactly on me, they are all my choices – I chose everybody from my generation down to people in their 30s, a preponderance of people based in London, but other people based in LA, but by no means all, and people that hate each other, and people who don't know each other. And then many of us are doing a launch gig at the Architectural Association soon.

You’re not doing one at the Bartlett I presume! The AA is, after all, where a lot of Archigram began.

Yes, but the AA doesn't really have anything interesting going on, though it has a slightly better spirit.

And you're not tempted to go back into teaching, into these institutions to shake them up?

No. Nobody has asked me, is the simple answer. Nobody’s asked me.

figs.xix-xxii

Sir Peter Cook RA, founder of Archigram, former Director the Institute for Contemporary Art, London (the ICA) and Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London has been a dominate figure in the architectural world for over half a century. His ongoing contribution to architectural innovation was recognised in 2007 when he was knighted by the Queen for his services to architecture. Cook’s achievements with radical experimentalist group Archigram have been the subject of numerous publications and public exhibitions and were recognised by the Royal Institute of British Architects in 2002, when members of the group were awarded the RIBA’s highest award, the Royal Gold Medal.

Cook continuing work as a lecturer of considerable renown makes him a familiar voice within cultural institutions around the world, where many have enjoyed an opportunity to hear Cook expound (among other subjects) upon his love affair with the slithering, the swarming and the spooky.

Cook and his studio has from the very beginning made waves in architectural circles. However, it was with the construction of the Kunsthaus Museum in Graz, Austria that his work was brought to a wider public. A process that continued with the completion of the Vienna Business and Economics University’s Departments of Law and Central Administration Buildings and the Abedian School of Architecture in Australia’s Bond University. The Drawing Studio for Arts University Bournemouth was his first UK building completed in 2016 and followed soon after with the Innovation Studio for the same campus. He also has built in Osaka, Nagoya, Berlin, Frankfurt and Madrid.

Peter Cook Architecture Studio are currently working on projects in LA, South Korea and the Middle East.

www.petercookarchitecture.com

Circa is a relatively new press, rooted in a wealth of publishing experience. The company was founded in London, in 2014, by David Jenkins, who over the past thirty years has conceived and edited critically acclaimed books on architecture and design for some of the world’s leading publishers.

Circa like to work with creative people who are passionate about what they do, and to reflect that passion in beautiful books with the highest editorial and production values. Their programme embraces ‘visual culture’ in all its forms, from books on architecture, to titles on art, design, and photography, with some things for younger readers too. Above all, they are motivated by great writing and compelling ideas.

www.circa.press

Circa like to work with creative people who are passionate about what they do, and to reflect that passion in beautiful books with the highest editorial and production values. Their programme embraces ‘visual culture’ in all its forms, from books on architecture, to titles on art, design, and photography, with some things for younger readers too. Above all, they are motivated by great writing and compelling ideas.

www.circa.press