Our highlights from Berlin Art Week 2025

We took a trip to Berlin to celebrate the capital city’s cultural scene over the 2025 edition of Berlin Art Week. In doing so not only did we discover a rich breadth of art, but also some incredible architectural settings of all eras & genres.

City art weeks are pretty common around the world now, but

not many can claim to be as large as Berlin’s. With over 100 museums,

collections, galleries, and project spaces taking part – not to mention the Positions

art fair – an already culturally-rich capital is positively saturated in

creativity and energy for five days of the year.

recessed.space visited and while we can’t claim to have touched much beneath the surface of what was on offer, we found some pretty exciting projects that, of course, can be visited over the coming months.

recessed.space visited and while we can’t claim to have touched much beneath the surface of what was on offer, we found some pretty exciting projects that, of course, can be visited over the coming months.

ABOUT BERLIN ART WEEK

Beyond the art itself, projects such as Art Week offer a great excuse to explore the architectural heritage of the city, to discover pop-up project spaces, to take the metro to suburbs that you may not have visited but needed an artistic excuse.

It’s not just architect-designed cultural spaces – from the huge Mies van der Rohe-designed Neue Nationalgalerie to the perfectly-proportioned but somewhat smaller Schinkel Pavillon, rebuilt by Bauhaus architect Richard Paulick in 1968 – but also spaces that have been adopted for cultural use.

These vary from the tiny underground station vitrine turned into a jewell-box gallery by Passage, through to the new CCA Berlin that has taken over the remarkable postwar former-office building of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church.

Beyond the art itself, projects such as Art Week offer a great excuse to explore the architectural heritage of the city, to discover pop-up project spaces, to take the metro to suburbs that you may not have visited but needed an artistic excuse.

It’s not just architect-designed cultural spaces – from the huge Mies van der Rohe-designed Neue Nationalgalerie to the perfectly-proportioned but somewhat smaller Schinkel Pavillon, rebuilt by Bauhaus architect Richard Paulick in 1968 – but also spaces that have been adopted for cultural use.

These vary from the tiny underground station vitrine turned into a jewell-box gallery by Passage, through to the new CCA Berlin that has taken over the remarkable postwar former-office building of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church.

AT HAMBURGER BAHNHOF

The centre of Berlin Art Week is the Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart, a former mid 19th century train station and now the contemporary component of the National Gallery. It is fronted by a garden, containing planted and sculpted artworks, and also a place which served as the Berlin Art Week hub as well as the (very busy!) launch party.

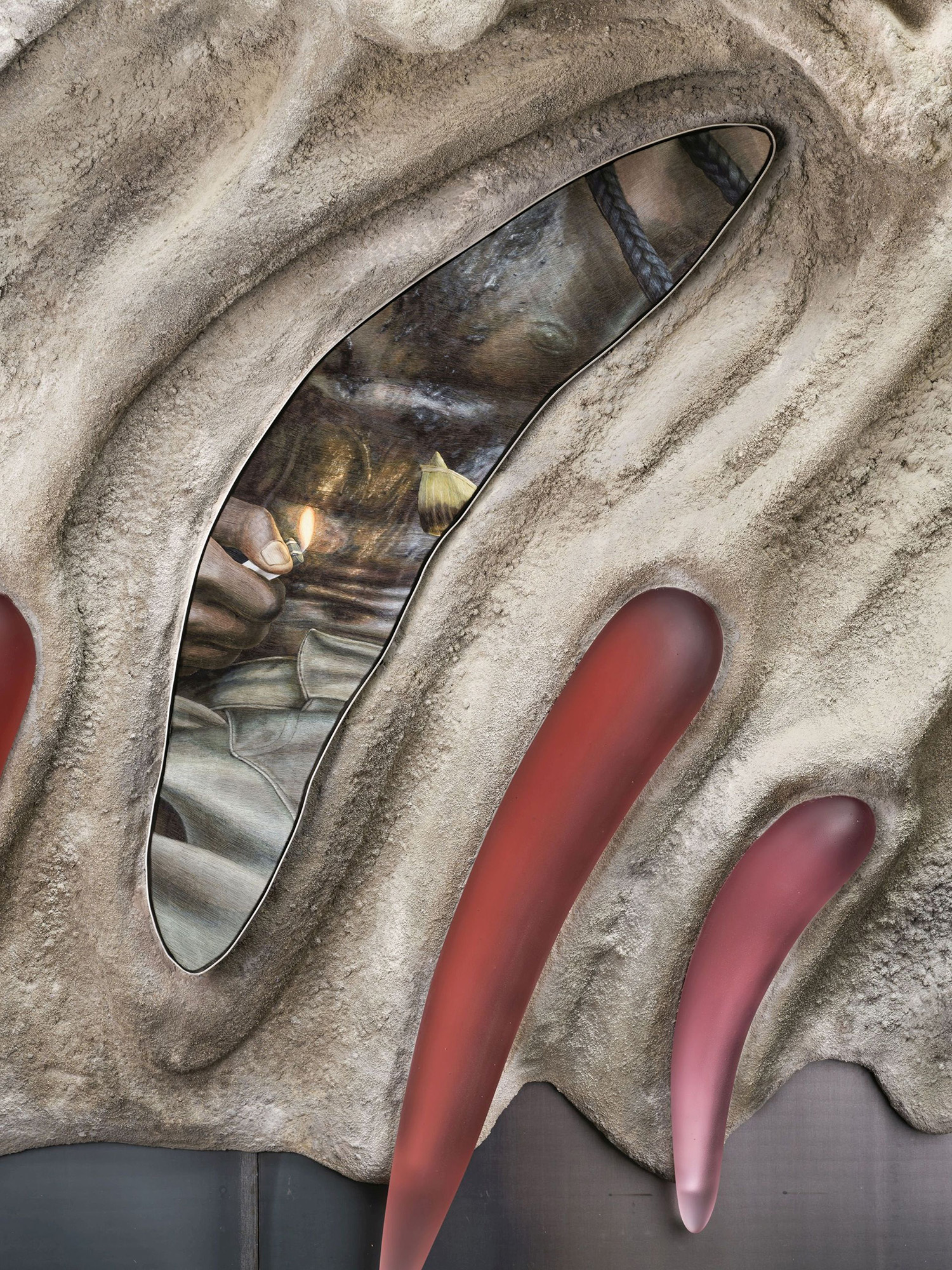

Inside, the main hall of the enormous, sprawling building is taken over by an organic, absorbing work by Czech artist Klára Hosnedlová. Glass, concrete, flax, hemp, thread, sand, and metal is alchemically turned into what reads as cultivation growing through the floors and taking over the monumental space.

All the materials are from the artist’s local lands of Bohemia and Moravia, speaking to folkloric processes entangling with brutalist architectural ideas, resulting in a place of ambiguous memory with a somewhat sinister H.R. Giger vibe.

The centre of Berlin Art Week is the Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart, a former mid 19th century train station and now the contemporary component of the National Gallery. It is fronted by a garden, containing planted and sculpted artworks, and also a place which served as the Berlin Art Week hub as well as the (very busy!) launch party.

Inside, the main hall of the enormous, sprawling building is taken over by an organic, absorbing work by Czech artist Klára Hosnedlová. Glass, concrete, flax, hemp, thread, sand, and metal is alchemically turned into what reads as cultivation growing through the floors and taking over the monumental space.

All the materials are from the artist’s local lands of Bohemia and Moravia, speaking to folkloric processes entangling with brutalist architectural ideas, resulting in a place of ambiguous memory with a somewhat sinister H.R. Giger vibe.

The nature theme continues. Soil is now an overused

material in art, often piled on a gallery floor as lazy symbolism for “the

world, yeah, we don’t look after it” – but in Colombian Delcy Morelos’ hands

it is used in far more sublime ways. Her earth is sculpted with geometric

precision, creating an architecture with reveals large enough for a visitor to

retreat into darkened corners. Morales’ artistic practice is rooted in Colombian

indigenous communities and their right to and respect of land, her sculpture

here containing not only material but also evidence of struggle, memory, and

violence.

In another suite of gallery rooms, Nigerian Toyin Ojih Odutola presents a series of drawings from the last decade across various mediums. Her portraits of various characters, often within public spaces, are not hung as a traditional gallery show, however. The whole installation reads as a fictional station on the U-Bahn, with tiled walls and columns ventilation units and even a faux route map on the wall. It’s an inventive, playful way to position her individuals, all unique with their own story, but momentarily converging in this collective space.

In another suite of gallery rooms, Nigerian Toyin Ojih Odutola presents a series of drawings from the last decade across various mediums. Her portraits of various characters, often within public spaces, are not hung as a traditional gallery show, however. The whole installation reads as a fictional station on the U-Bahn, with tiled walls and columns ventilation units and even a faux route map on the wall. It’s an inventive, playful way to position her individuals, all unique with their own story, but momentarily converging in this collective space.

figs. viii-xiii

HAUS DER KULTUREN DER WELT

The Haus der Kulturen der Welt is a remarkable parabolic building in the Tiergarten park. In 1848, when Berliners were protesting as across much of Europe, the site was a gathering space for activism and anger. At the start of the 20th century, the area had a large Jewish population, through until the National Socialist’s rise. Having suffered heavy bombing, postwar the area became the site of the 1957 International Building Exhibition and what is now the Haus der Kulturen was built as the Kongresshalle, a gift from the US Government to West Berlin.

With such loaded history in context and design, it is perhaps fitting then that the space is hosting a major exhibition on fascism – a sadly timely project with the rise of the far right in Germany and across the world. In an essay that can be read online, curator Cosmin Costinaș asks: “What is art’s role in this? How has art been complicit in this turn? How do aesthetic regimes play into it?”

The Haus der Kulturen der Welt is a remarkable parabolic building in the Tiergarten park. In 1848, when Berliners were protesting as across much of Europe, the site was a gathering space for activism and anger. At the start of the 20th century, the area had a large Jewish population, through until the National Socialist’s rise. Having suffered heavy bombing, postwar the area became the site of the 1957 International Building Exhibition and what is now the Haus der Kulturen was built as the Kongresshalle, a gift from the US Government to West Berlin.

With such loaded history in context and design, it is perhaps fitting then that the space is hosting a major exhibition on fascism – a sadly timely project with the rise of the far right in Germany and across the world. In an essay that can be read online, curator Cosmin Costinaș asks: “What is art’s role in this? How has art been complicit in this turn? How do aesthetic regimes play into it?”

This is not a small exhibition, and as it doesn’t seek a

singular answer, it is also sprawling, and becomes somewhat disjointed in

places due to it trying to roll everything from the manosphere to crypto networks

into its orbit, though there are stand out moments where art can speak to the

key concerns.

Niklas Goldbach’s images of seemingly paradise landscapes are actually promotional images of Center Parcs’ themed environments, but with early AI technology expanding the image to create what it reads as the inferred utopia. They speak to the colonial gaze, control of landscape, and the digital aesthetic, all of which feed into the underlying theme.

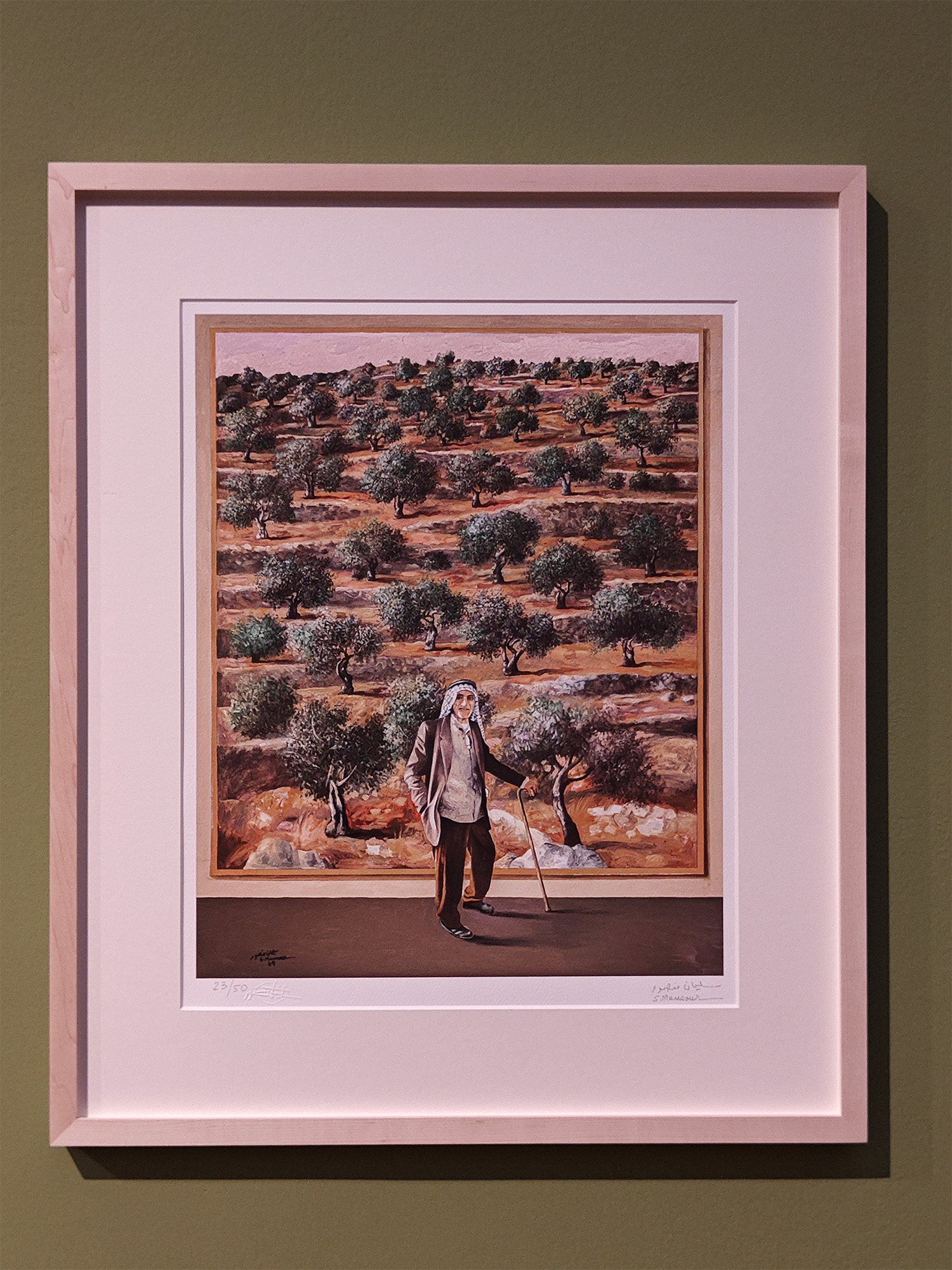

Elsewhere, Sunwoo Hoo’s vertical-scroll urban landscape – referencing historic South East Asian landscape art – speaks to the online experiences with rising hate, homophobia, and trolling. A time-separated diptych by Hannah Höch from 1933 and 1945 are chilling, while we are reminded of the immediate violence in the Gaza Strip, now determined as genocide by the UN, through Sliman Mansour’s weighty political drawings depicting traditional activities from Palestine and Bethlehem – showing resilience and hope in the work, important inclusions in such an exhibition in Germany today.

Niklas Goldbach’s images of seemingly paradise landscapes are actually promotional images of Center Parcs’ themed environments, but with early AI technology expanding the image to create what it reads as the inferred utopia. They speak to the colonial gaze, control of landscape, and the digital aesthetic, all of which feed into the underlying theme.

Elsewhere, Sunwoo Hoo’s vertical-scroll urban landscape – referencing historic South East Asian landscape art – speaks to the online experiences with rising hate, homophobia, and trolling. A time-separated diptych by Hannah Höch from 1933 and 1945 are chilling, while we are reminded of the immediate violence in the Gaza Strip, now determined as genocide by the UN, through Sliman Mansour’s weighty political drawings depicting traditional activities from Palestine and Bethlehem – showing resilience and hope in the work, important inclusions in such an exhibition in Germany today.

figs. xvii-xix

NEUE NATIONALGALERIE

Opened in 1968, the Mies van der Rohe-designed arts centre, renovated by David Chipperfield Architects in 2021, is one of Berlin’s most remarkable buildings. Split into two parts, the ground floor is one large, gridded and open expanse – a unique exhibition space that isn’t always easy for curators to contend with but can on occasion sing with the right works. Downstairs is far more traditional, with light-controlled rooms and the permanent collection.

The large internal expanse, bounded by clear glass, is currently occupied by a major retrospective to Brazilian artist Lygia Clark, who passed in 1988. A mixed show comprising abstract painting to participatory performance, it’s the kind of show that can work in the difficult gallery – a presentation that celebrates the openness and uniformity through activation and play rather than trying to stick to traditional exhibition principles.

Since May, but ending over Berlin Art Week, a site-specific fog sculpture by Japanese artist Fujiko Nakaya had occupied the adjoining sculpture garden. Designed to fight against the rigid order of Mies’ structure, the artist’s pure water fog created an ephemeral dislocation from the place.

Opened in 1968, the Mies van der Rohe-designed arts centre, renovated by David Chipperfield Architects in 2021, is one of Berlin’s most remarkable buildings. Split into two parts, the ground floor is one large, gridded and open expanse – a unique exhibition space that isn’t always easy for curators to contend with but can on occasion sing with the right works. Downstairs is far more traditional, with light-controlled rooms and the permanent collection.

The large internal expanse, bounded by clear glass, is currently occupied by a major retrospective to Brazilian artist Lygia Clark, who passed in 1988. A mixed show comprising abstract painting to participatory performance, it’s the kind of show that can work in the difficult gallery – a presentation that celebrates the openness and uniformity through activation and play rather than trying to stick to traditional exhibition principles.

Since May, but ending over Berlin Art Week, a site-specific fog sculpture by Japanese artist Fujiko Nakaya had occupied the adjoining sculpture garden. Designed to fight against the rigid order of Mies’ structure, the artist’s pure water fog created an ephemeral dislocation from the place.

PASSAGE

Founded last year, Passage is a curatorial platform designed to celebrate and occupy a single vitrine within Hermannplatz U-Bahn station. Opened in 1926, and one of the busiest stations on the system, the architecture by Alfred Grenander and Alfred Fehse is largely still intact. It was designed with direct access to the Karstadt department store (what would Walter Benjamin have made of that!) and the vitrine now occupied by Passage was a public extension of that site of commercial display.

Currently on show is Gerd Rohling’s seemingly antique vessels, sat on glass shelves with value and importance. They are, in fact made of plastic waste the artist fishes out of the Guld of Naples, carefully moulded and lit. The idea of showing work in a public vitrine is not unique, it’s an idea repeated across many places, but it does work extremely well in Hermannplatz, and perhaps causes a moments pause for a passerby, or triggers an abstract idea that recurs through their day.

Founded last year, Passage is a curatorial platform designed to celebrate and occupy a single vitrine within Hermannplatz U-Bahn station. Opened in 1926, and one of the busiest stations on the system, the architecture by Alfred Grenander and Alfred Fehse is largely still intact. It was designed with direct access to the Karstadt department store (what would Walter Benjamin have made of that!) and the vitrine now occupied by Passage was a public extension of that site of commercial display.

Currently on show is Gerd Rohling’s seemingly antique vessels, sat on glass shelves with value and importance. They are, in fact made of plastic waste the artist fishes out of the Guld of Naples, carefully moulded and lit. The idea of showing work in a public vitrine is not unique, it’s an idea repeated across many places, but it does work extremely well in Hermannplatz, and perhaps causes a moments pause for a passerby, or triggers an abstract idea that recurs through their day.

JULIA STOSCHEK FOUNDATION

Perhaps the most un-Berlin exhibition across the Art Week offerings, there could be assumed to be something slightly odd about travelling from London to experience an exhibition largely about London urban space, neoliberal landscapes, and the specifically British modes of policing and controlling society. But sometimes it takes relocating a subject to truly see it, and in any case if no UK institution wanted to offer Mark Leckey such an overdue survey show then it’s just as well the Julia Stoschek Foundation stepped up, because it’s excellent.

One of the most acerbic and critically cutting of living British artists, Leckey is interested at the intersections of place, culture, and archive. This could be found footage, such as in the landmark film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore that we wrote about recently (00286), urban corners such as bus stops, underpasses, or benches, or indeed the spaces of social media and digital sharing.

Perhaps the most un-Berlin exhibition across the Art Week offerings, there could be assumed to be something slightly odd about travelling from London to experience an exhibition largely about London urban space, neoliberal landscapes, and the specifically British modes of policing and controlling society. But sometimes it takes relocating a subject to truly see it, and in any case if no UK institution wanted to offer Mark Leckey such an overdue survey show then it’s just as well the Julia Stoschek Foundation stepped up, because it’s excellent.

One of the most acerbic and critically cutting of living British artists, Leckey is interested at the intersections of place, culture, and archive. This could be found footage, such as in the landmark film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore that we wrote about recently (00286), urban corners such as bus stops, underpasses, or benches, or indeed the spaces of social media and digital sharing.

This exhibition of over 50 works by Leckey has all these and

more. The Camden Bench, designed by the council as hostile architecture to ward

off skateboarders, the homeless, graffiti artists and, well, really anyone who

isn’t momentarily pausing from consuming, is here turned into a gallery bench

to view a film. A London bus stop, drenched in sodium streetlights, becomes a

video display case for an unnerving and compelling film utilising found footage

of a teenager smashing through an identical bus stop, but here remixed and

turned into a surround sound opera.

At every turn, new worlds are created then distorted. Pop culture fuses with medieval iconography, disposable moments are made solid, and a concrete dolosse, used to prevent rough seas eroding the coast, is inflated and turned into softplay. Several of the artist’s video works are presented, including a grand presentation of the aforementioned Fiorucci. This show deserves to travel, ideally to London to show the city back at itself in a darkly critical way.

At every turn, new worlds are created then distorted. Pop culture fuses with medieval iconography, disposable moments are made solid, and a concrete dolosse, used to prevent rough seas eroding the coast, is inflated and turned into softplay. Several of the artist’s video works are presented, including a grand presentation of the aforementioned Fiorucci. This show deserves to travel, ideally to London to show the city back at itself in a darkly critical way.

figs.xxix-xxxi

LAS ART FOUNDATION

At last year’s Venice Biennale of Art we wrote about a huge, blue pop-up tent enclosing otherworldly undersea creatures (00231). It was a project by Josèfa Ntjam for Berlin immersive art organisation LAS Art Foundation who since 2019 have been creating unexpected, site-responsive, and memorable projects in the German capital’s non-gallery spaces. Their latest project is a double header taking over an upper floor of a long closed-down CANK discount department store in Neukölln.

LAS are known for their large-scale, sublime technological environments, but the first side of the raw, dark, space is something altogether more paired back. Offered up to touring Black art collective CEL, the room is fundamentally a space awaiting activation through events, music, conversation, and solidarity.

At the deeper end of the space, a form slowly emerges from the dry ice and lasers. A wide-based pyramid has one side opened into shallow-step seating to view a video from Christelle Oyiri. Hauntology of an OG draws connections between Memphis, Tennessee, and ancient Egypt amongst other spiritual and conflict-heavy spaces. The celebrated Bass Pro Shops Pyramid, an unlikely geometric moment in the city’s architecture, acts as a motif.

At last year’s Venice Biennale of Art we wrote about a huge, blue pop-up tent enclosing otherworldly undersea creatures (00231). It was a project by Josèfa Ntjam for Berlin immersive art organisation LAS Art Foundation who since 2019 have been creating unexpected, site-responsive, and memorable projects in the German capital’s non-gallery spaces. Their latest project is a double header taking over an upper floor of a long closed-down CANK discount department store in Neukölln.

LAS are known for their large-scale, sublime technological environments, but the first side of the raw, dark, space is something altogether more paired back. Offered up to touring Black art collective CEL, the room is fundamentally a space awaiting activation through events, music, conversation, and solidarity.

At the deeper end of the space, a form slowly emerges from the dry ice and lasers. A wide-based pyramid has one side opened into shallow-step seating to view a video from Christelle Oyiri. Hauntology of an OG draws connections between Memphis, Tennessee, and ancient Egypt amongst other spiritual and conflict-heavy spaces. The celebrated Bass Pro Shops Pyramid, an unlikely geometric moment in the city’s architecture, acts as a motif.

SPRÜTH MAGERS

Gallery behemoth Sprüth Magers has two shows in their Berlin outpost. Their Mitte space was once a dancehall, but with such high ceilings one wonders what spectacular moves were once thrown that required such headspace.

While the main gallery is vertiginous in height, the presentation of works by Finnish painter Henni Alftan sticks to a uniform low-level hang. Her images read as still frames from imaginary films, but with an uncanny air. There is a strong sense of architecture from the in- and outside, but stripped back of emotion, and turned into geometric outlines of emptiness, at once a celebration of paint as a form, but also remarking on its limits in representation when dehumanised and distant from life.

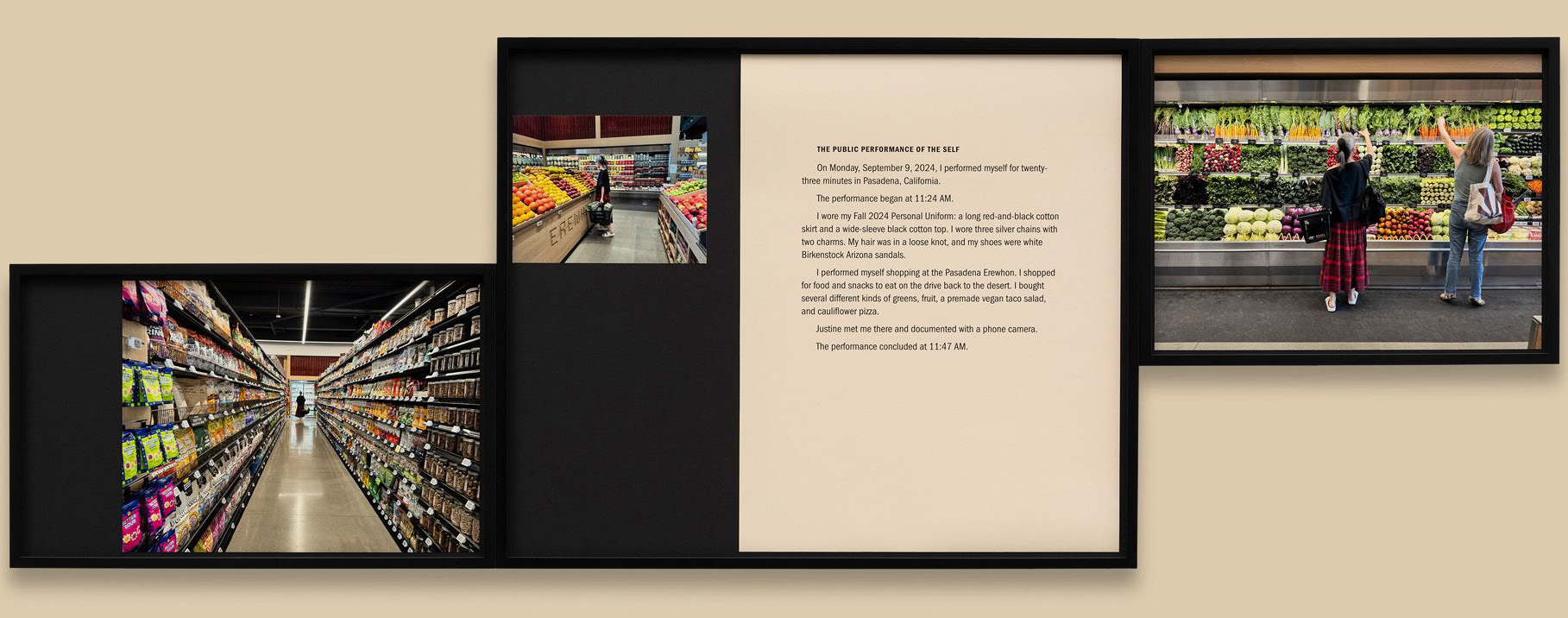

Upstairs, Andrea Zittel shows neatly composed images documenting moments of her daily life. Her Public Performance of the Self questions what being an artist is, provocatively throwing out there the idea that today, just living and being is a work of art. She is consensually surveilled carrying out daily activities, images of the act accompanied by a small descriptive text outlining the performance. The American artist celebrated for architecture and residential experiments in living on her Joshua Tree High Desert Test Sites estate, is here considering existence at a more intimate scale.

Gallery behemoth Sprüth Magers has two shows in their Berlin outpost. Their Mitte space was once a dancehall, but with such high ceilings one wonders what spectacular moves were once thrown that required such headspace.

While the main gallery is vertiginous in height, the presentation of works by Finnish painter Henni Alftan sticks to a uniform low-level hang. Her images read as still frames from imaginary films, but with an uncanny air. There is a strong sense of architecture from the in- and outside, but stripped back of emotion, and turned into geometric outlines of emptiness, at once a celebration of paint as a form, but also remarking on its limits in representation when dehumanised and distant from life.

Upstairs, Andrea Zittel shows neatly composed images documenting moments of her daily life. Her Public Performance of the Self questions what being an artist is, provocatively throwing out there the idea that today, just living and being is a work of art. She is consensually surveilled carrying out daily activities, images of the act accompanied by a small descriptive text outlining the performance. The American artist celebrated for architecture and residential experiments in living on her Joshua Tree High Desert Test Sites estate, is here considering existence at a more intimate scale.

figs.xxxvii-xxxix

THE HAMBURGER BAHNHOF (AGAIN)

Returning to Hamburger Bahnhof, the former station has opened up a major new exhibition by Petrit Halilaj to coincide with Berlin Art Week. An artist interested in the theatrical and fantastical, Halilaj has created a museum version of his first operatic work, Syrigana. The artist was born in what is now Kosovo but was Yugoslavia in 1986, and his understanding of post-war territory, society, and architecture infuses his practice.

Syrigana takes its name from a 3000 year-old village near Runik, Halilah’s hometown, which since 2016 has been protected as an archaeological and prehistoric site. Folk tales record it as the setting for Adam and Eve’s marriage, this narrative turned by the artist into a queer romance between a fox and rooster who arrived in the region within a NATO peacekeeping helicopter. This is no ordinary opera, here presented as a series of sculptural set pieces with the score playing over.

Returning to Hamburger Bahnhof, the former station has opened up a major new exhibition by Petrit Halilaj to coincide with Berlin Art Week. An artist interested in the theatrical and fantastical, Halilaj has created a museum version of his first operatic work, Syrigana. The artist was born in what is now Kosovo but was Yugoslavia in 1986, and his understanding of post-war territory, society, and architecture infuses his practice.

Syrigana takes its name from a 3000 year-old village near Runik, Halilah’s hometown, which since 2016 has been protected as an archaeological and prehistoric site. Folk tales record it as the setting for Adam and Eve’s marriage, this narrative turned by the artist into a queer romance between a fox and rooster who arrived in the region within a NATO peacekeeping helicopter. This is no ordinary opera, here presented as a series of sculptural set pieces with the score playing over.

Other spaces of the exhibition further explore notions of

fracture, reassembly, trauma, and hope. A large architectural construction

recalls the ruins of the 1950s Runik House of Culture. The building, once home

to a cinema, theatre, and library, saw its vibrant cultural uses ended during

1990s censorship and repression before falling into ruin. Halilaj has helped

clear the site of debris and inject it with art once again, creating musical

projects for a shell which will soon undergo a form of reconstruction. The

artist’s installation here uses some of the bricks and architectural salvage as

markers of memory, carrying the histories but also stoically proposing a

rebuilt future.

Elsewhere, a white horse stands alone on a pink lake. It speaks to the story of Halilaj’s great-great-grandfather, Baba Gan, a storyteller who is said to have ridden such a grand white horse, but was assassinated during the 1912 Serbian invasion of Kosovo. There is a beauty and creative hope in this set piece, but also a somewhat polluted, barren sense of despair – we are again in a time when storytellers, journalists, and those who document violent truths are again targeted as threats to authority.

Elsewhere, a white horse stands alone on a pink lake. It speaks to the story of Halilaj’s great-great-grandfather, Baba Gan, a storyteller who is said to have ridden such a grand white horse, but was assassinated during the 1912 Serbian invasion of Kosovo. There is a beauty and creative hope in this set piece, but also a somewhat polluted, barren sense of despair – we are again in a time when storytellers, journalists, and those who document violent truths are again targeted as threats to authority.

figs.xxxx-xxxxii

THE SCHINKEL PAVILION

A joy of Art Week is being able to hop between remarkable moments of architecture with art sometimes the reason, sometimes an excuse. British artist Issy Wood’s work is fascinating, with captured moments of the everyday world but infused with hints of melancholy, art history, pop culture, and intimate insight. However, any artist who shows in the remarkable jewel box that is the Schinkel Pavilion is always in a fight for winning the visitor’s attention.

Originally constructed in 1825 as a summer house for King Frederick William III, the Karl Friedrich Schinkel-designed building carriers an air of the neoclassical. But there are twists of detail, colour, and shimmering light that break the Palladian neatness in form and ruptures of symmetry. Nealy completely destroyed in WWII, it was rebuilt in the late 1960s by Richard Paulick, an architect who oversaw large swathes of East German reconstruction, including the famed Plattenbau. His regular architecture was starkly modernist and ordered, but in the Schinkel reconstruction there is a moment of unlikely DDR historic celebration, albeit fused with modernist fittings and elements.

A joy of Art Week is being able to hop between remarkable moments of architecture with art sometimes the reason, sometimes an excuse. British artist Issy Wood’s work is fascinating, with captured moments of the everyday world but infused with hints of melancholy, art history, pop culture, and intimate insight. However, any artist who shows in the remarkable jewel box that is the Schinkel Pavilion is always in a fight for winning the visitor’s attention.

Originally constructed in 1825 as a summer house for King Frederick William III, the Karl Friedrich Schinkel-designed building carriers an air of the neoclassical. But there are twists of detail, colour, and shimmering light that break the Palladian neatness in form and ruptures of symmetry. Nealy completely destroyed in WWII, it was rebuilt in the late 1960s by Richard Paulick, an architect who oversaw large swathes of East German reconstruction, including the famed Plattenbau. His regular architecture was starkly modernist and ordered, but in the Schinkel reconstruction there is a moment of unlikely DDR historic celebration, albeit fused with modernist fittings and elements.

CCA BERLIN

One of Berlin’s newest art spaces cuckoos itself inside an architecture designed for an entirely different function, but in doing so it creates one of the cities most distinct and calming experiences for viewing work. CCA Berlin was founded in 2022 by Fabian Schöneich, modelled on London’s ICA as a space for international creative, multidisciplinary inquiry. It can be found in former church office of the starkly modernist postwar reconstruction of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. A 1943 bombing raid ruined the original 1890s church, with Egon Eiermann’s 1950s design then pulling down the ruined remaining structure but – after public outcry – leaving the church tower standing.

Having discovered the empty former church office space during Berlin’s Open House festival, the protected building is now the CCA, and while the outside streets are bustling, inside it feels poetically protected and filled with soft light, perfect for viewing the current show of works by Lukas Luzius Leichtle.

Leichtle’s awkward self portraits show parts of the body that cannot be seen by the self, or familiar parts – such as the hands – slightly awkward and dislocated from the norm. Tightly cropped, these paintings are intimate, intense, and rooted in deep focus, both in observation and a practice that sees the artist repeatedly rubbing the surface with sandpaper to create a flatness that only seems flatter in the uniform light of the CCA.

One of Berlin’s newest art spaces cuckoos itself inside an architecture designed for an entirely different function, but in doing so it creates one of the cities most distinct and calming experiences for viewing work. CCA Berlin was founded in 2022 by Fabian Schöneich, modelled on London’s ICA as a space for international creative, multidisciplinary inquiry. It can be found in former church office of the starkly modernist postwar reconstruction of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. A 1943 bombing raid ruined the original 1890s church, with Egon Eiermann’s 1950s design then pulling down the ruined remaining structure but – after public outcry – leaving the church tower standing.

Having discovered the empty former church office space during Berlin’s Open House festival, the protected building is now the CCA, and while the outside streets are bustling, inside it feels poetically protected and filled with soft light, perfect for viewing the current show of works by Lukas Luzius Leichtle.

Leichtle’s awkward self portraits show parts of the body that cannot be seen by the self, or familiar parts – such as the hands – slightly awkward and dislocated from the norm. Tightly cropped, these paintings are intimate, intense, and rooted in deep focus, both in observation and a practice that sees the artist repeatedly rubbing the surface with sandpaper to create a flatness that only seems flatter in the uniform light of the CCA.