In search of oracular places at the 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts

To architects, the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana is known

as being Jože Plečnik’s city, the architect shaping the place as much as Gaudí

did in Barcelona. But the cultural history of the place goes far beyond his

landmark urban set pieces, with a rich artistic history including a Biennale of

Graphic Arts, founded in 1955 & now operating as a platform & knowledge

exchange for design. Lorenzo Graf & Riccardo Buck visited the 36th

edition to discover works in galleries as well as across the city’s spaces.

The 36th Biennale of Graphic Arts, titled The Oracle, invites visitors on an agreeable stroll through the city centre of Ljubljana. Within walking distance from each other, the main venues of this edition, curated by Chus Martínez, are aligned with the picturesque Jakopič Promenade. Redesigned by the renowned national architect Jože Plečnik in the 1930s, this civic space extends the prominent Cankar Street into the Tivoli Park, creating a strong visual axis that connects Tivoli Castle with Prešeren Square, Triple Bridge, and Ljubljana Castle. Standing in front of Tivoli Castle, the operative base and exhibition venue of the biennale since 1989, we were met with a powerful vista, a transparent arrow neatly cutting through the city. Following the same logic of such representative panoramas, Plečnik also designed an open-air auditorium in the park for concerts and theatre pieces.

figs.i-iii

In Sinzo Aanza’s The Irregular Line and Kathrin Siegriest’s A Shade We Share I (both 2025), the only two outdoor artworks presented by Martínez, this panoptical gaze is subtly complicated. Installed along the promenade, Aanza’s series of drawings, paintings, and quotations printed on billboards take the regularity of the line as a signifier of the ordering gaze of colonialism. The work of the Congolese artists offers an antidote to a difficult legacy of the Western oracle, recalling that the most famous one, the Delphic, claimed its location as the world’s centre (omphalos), and influenced political decisions about colonial expansion.

Siegriest’s installation, made of discarded emergency parachutes hanging in the shape of inverted pyramids, stands at the feet of the auditorium. While the material evokes associations with falling, its wind-driven inflation and deflation continuously recall a fire balloon striving to rise upward. Drawn to it, like the hordes of children playing in the park, we too stepped inside its changeable forms moved by the slightest breeze – our field of vision filled with the mesh’s vivid colours, our ears soothed by its soft, rustling sound.

figs.iv,v

However, oracles would commonly look at more hidden places. Dreams, leaves of sacred trees, flight patterns of birds, and intestines of animals were among the favoured sites of divination in Graeco-Roman antiquity. This fascination with hidden signs may explain the biennale’s preference for enclosed venues, shielded from the outside world. The immersive, often darkened exhibition spaces create intimate environments that invite visitors to delve into the artists’ works, which take up entire rooms in most cases. The exhibition as whole is skilfully anchored by the recurring presence of two distinct Slovene artists, Silvan Omerzu and Svetlana Makarovič, whose works are installed at the entrance of each venue. This curatorial strategy provides a sense of grounding, especially given that the biennale’s theme of the oracle is stretchable enough to encompass a wide range of topics.

Omerzu’s installations of stylised puppets resonate with Slovenia’s literary tradition, myths, and history. Never unambiguous, his wooden puppets gesture to complex issues of military rule, false humanistic morality, and illness, often embodying opposing forces simultaneously. The positions of the figures and their enigmatic interactions create oracular places that call for acts of interpretation. Similarly, the poems by Makarovič, often beautifully displayed alongside Omerzu’s puppets, strike a similar tone. Drawn from her celebrated collection Aloness (2002), her rhythmic ballads rely on temporal patterns or counting schemes to address oppressive and dark themes, as in The Clock: “The first hour beats,/ death still has not come,/ the second hour beats,/ mist there is outside,/ the third hour beats,/ quiet hunger […]”. Her oracular language is embodied — a close-up on sensory perceptions and the uncertainty of a nevertheless carefree lyrical subject.

figs.vi-viii

The historical book illustrations by Estonian artist Aili Vint felt like a glowing apparition to us. Placed at the heart of the Museum of Modern Art, the main venue, her small gouache paintings on paper show marine landscapes interwoven with elements remindful of bodily parts, rendered in the vibrant colours and style of mid-1970s Estonian geometric abstraction. These dream-like motifs, made of meticulously painted colour fields, reveal the influence of surrealism and op art in the exploration of a cosmic and metaphysical dimension – one regarded as an “art of elegant refusal”[1] during the Soviet era.

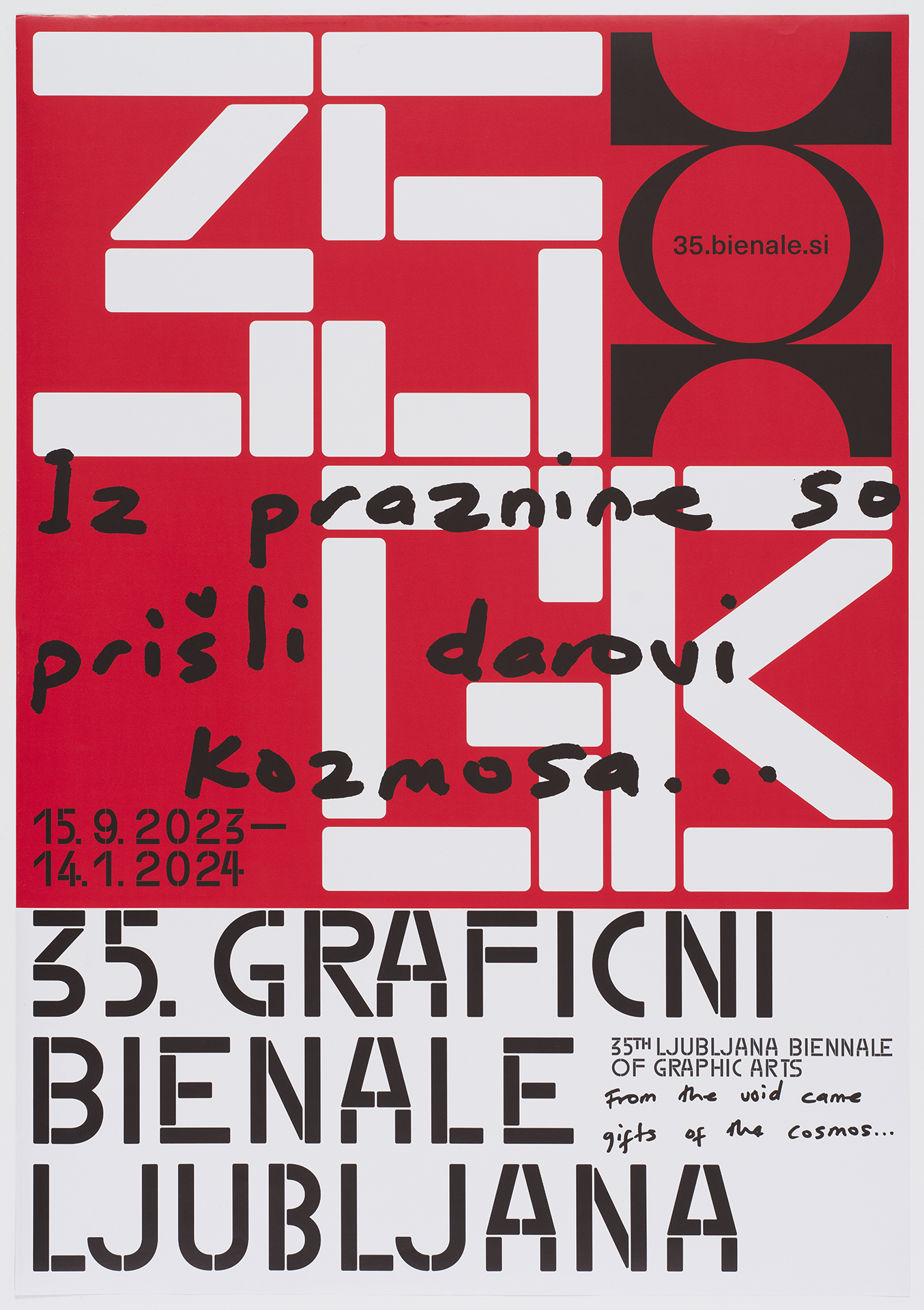

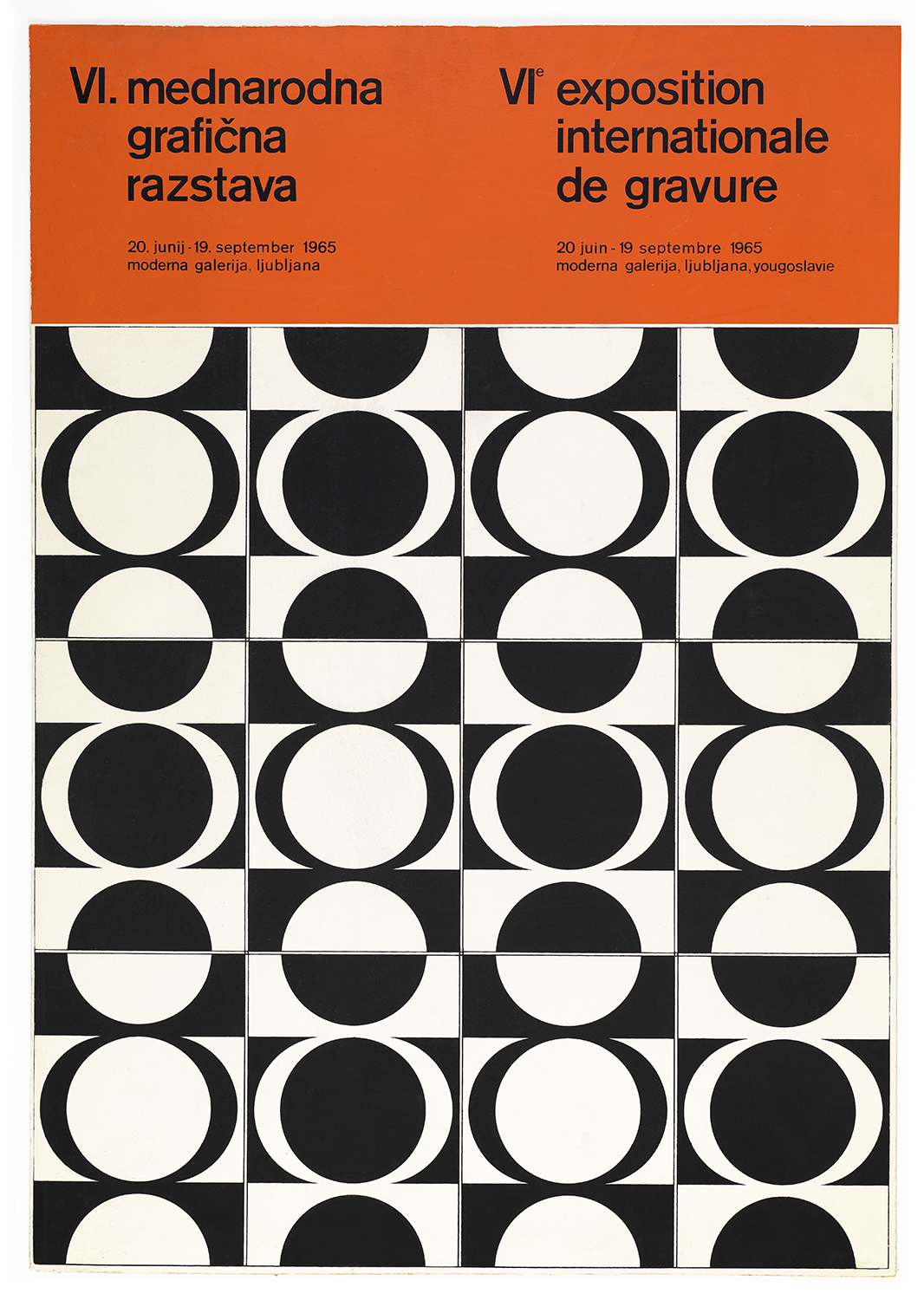

With its opaque and saturated colours, gauche is particularly well suited for illustration and poster design, situating the technique within the broader tradition of graphic arts, alongside better-known practices such as intaglio printing. Graphic arts? True, after all, this is the 70th anniversary of the grafični bienale: “the oldest event to systematically investigate the role and significance of printmaking”,[2] as art historian Vesna Teržan remarks. Yet, despite this milestone, Vint’s work remains the only example of graphic arts featured in the exhibition’s main section. This is not entirely surprising, given the biennale’s “transition to the paradigm post-media art“[3] in early 2000s. Nevertheless, the biennale keeps its historical title and logo – the latter borrowed from Ivan Picelj’s poster design for the 5th edition back in 1963 – and we, unapologetic, nostalgics cannot help but wonder why.

figs.ix-xi

But why not? Printmaking seems to find its way into the exhibition anyway – to our greatest delight. The two parallel exhibitions by Tejswini Narayan Sonawane (recipient of the last edition’s Grand Prize) and the collective Sreda v sredo (winner of the Audience Award) offer contemporary expressions of printmaking. We were particularly captivated by the exhibit of Sreda v sredo (SVS), a hidden gem at the S Gallery at Ljubljana Castle, curated by Božidar Zrisnki. This impressive venue is located beneath the courtyard of Ljubljana Castle. While the castle itself has stood as an unmistakable landmark overlooking the city for some five hundred years, the S Gallery has benefited from its extensive renovation (2000–2024). Adjacent to the castle’s historic underground service areas, once used for water collection, the exhibition space combines a brutalist use of concrete with the raw presence of untouched natural rock formations.

figs.xii-xiv

Founded in 2019 as a casual weekly gathering in a basement by Žiga Artnak, Urban Cerjak, and Matic Flajs, the collective SVS has since been exploring the manifold techniques of printmaking while cultivating the communal ethos of the print workshop. The serigraphy and intaglio prints on display at the S Gallery represent a selection of sheets produced together with guests and artists friends during open sessions organised as part of the 35th edition. Printmaking itself may also be understood as an oracular process — a collective and unpredictable interrogation of the engraved or etched matrix through press, ink, and paper.

figs.xv-xvii

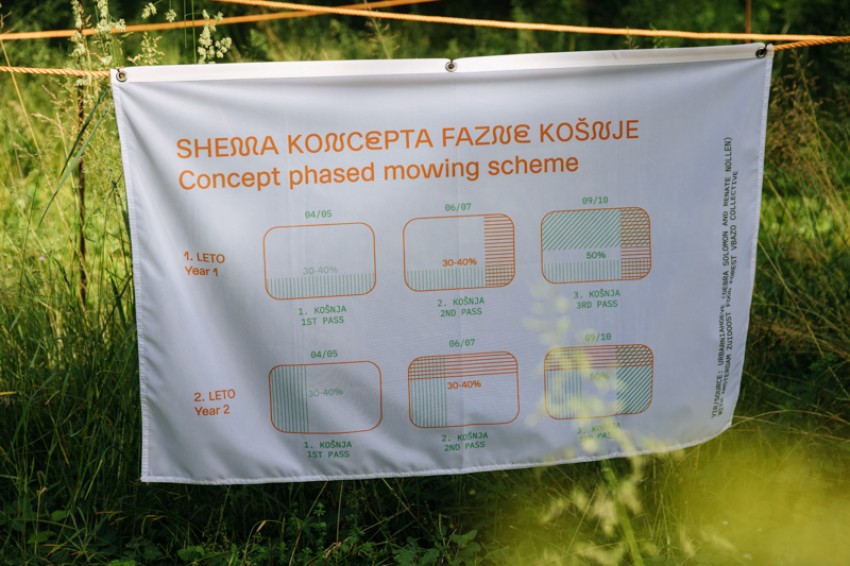

As oracular temples were traditionally located outside of the Greek cities, we were inspired to extend our walking route around Ljubljana. Following the stream of the Ljubljanica river away from the old town, we passed the socialist modernist apartment blocks of the neighbourhood of Nove Fužine from the early 1980s and began to notice certain signs. Enclosed by orange fences, typically used for construction sites, land plots of phase-mowed grass areas dot the urban landscape. These mysterious pockets of protected urban biodiversity have been crafted by Krater collective to establish “a speculative biodiversity corridor”[4] that cuts sideways through Ljubljana. This is made possible by the phased mowing approach rooted in the pre-Alpine land traditions.

figs.xviii-xx

Not part of this year’s biennale, this two-year project titled Crafting Biodiversity was developed by the multidisciplinary collective upon invitation by the Museum of Museum of Architecture and Design (MAO) in Ljubljana. A participant in the last biennale,[5] Krater regularly monitors and documents the transformations occurring within these parcels, working alongside biologists and other experts while speculating on the potential seeds of multispecies city-making. Enjoying the status of artworks primarily for bureaucratic reasons, these small sites of speculation and interpretation resonate with Chus Martínez’s reflections on the biennale’s theme of the oracle: “Art – all arts – assumes the existence of a tiny but meaningful spot from where to be free and dream and demand freedom and peace. This exhibition is about this tiny spot. […] This Biennale is, then, an oracular place, a place for interpretation”.[6]

figs.xxi-xxiii

[1] Sirje Helme quoted after: Mari Laanemets; Flight into Tomorrow:

Rethinking Artistic Practice in Estonia During the 1970s (Leonhard Lapin). ARTMargins2013; 2 (2): 137–162. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/ARTM_a_00050

[2] Vesna Teržan, “The Moment We Asked Mnemosyne to Guide Us…,” in Mnemosyne:

The Time of Ljubljana's Biennial of Graphic Arts, ed. Vesna Teržan

(Ljubljana: International Center of Graphic Arts, 2010), 52.

[3] “A brief outline of the event”, Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts,

accessed Sept. 10, 2025, https://bienale.si/en/about/.

[4] “Crafting Biodiversity”, Krater, accessed

Sept. 10, 2025, https://krater.si/en/projekti/obrt-vsezivosti.

[5] https://passe-avant.net/reviews/dreaming-buried-promises-anew-at-the-35th-ljubljana-biennale-zishi-han-lorenzo-graf-ibrahim-mahama-void-gift-cosmos

[6] Vesna Česen Rošker, Ajda Ana Kocutar, Chus Martínez, eds., The 36th

Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts: The Oracle - Exhibition Guide,exh.

cat. (2025).

The

Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts is one of the oldest biennials in the world.

It was founded in 1955 and will celebrate its 70th anniversary with its

upcoming edition this year. With its activities, it positioned Ljubljana and

Slovenian art into a global context, influenced the development of many similar

events around the world, and created an active network of knowledge exchange in

the field of graphic arts.

Today,

the Biennale is a vibrant, constantly shifting platform for artistic creation

and critical analysis of societal events. It is characterised by the

democratisation of art and culture and, at the same time, by elusive,

overlapping forms of knowledge, experience, and practice.

The

36th edition of the Biennale, under the artistic direction of Chus Martínez,

will be created in cooperation with a number of international partners (to be

announced) and national partners including the Museum of Modern Art (Moderna

galerija), under whose auspices the Biennale was held until the establishment

of the International Centre of Graphic Arts in 1986.

www.bienale.si

Lorenzo

Graf is a researcher and an independent curator based in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. His areas of interest encompass mental health politics, urban space, and improvisational infrastructure. He has worked at the Museum MMK für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, Frankfurter Kunstverein, and Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich. His independent curatorial practice includes projects and exhibitions at MEWO Kunsthalle Memmingen, Goethe-Institut Cyprus, and Goethe-Institut Nigeria among others. He is currently a PhD fellow of the Research Training Group "Organizing Architectures".

www.lorenzograf.com

Riccardo

Buck

studied painting at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan and musical composition in Treviso. For his thesis, he investigated the connections between music and painting in the 20th century, exploring the possibility of a translation between the two. In Berlin, he earned a master's degree in Visual and Media Anthropology from the Freie Universität. He paints using batik on paper and works as a gardener.

www.riccardobuck.com

www.lorenzograf.com

Riccardo

Buck

studied painting at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan and musical composition in Treviso. For his thesis, he investigated the connections between music and painting in the 20th century, exploring the possibility of a translation between the two. In Berlin, he earned a master's degree in Visual and Media Anthropology from the Freie Universität. He paints using batik on paper and works as a gardener.

www.riccardobuck.com

images

fig.i Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vivamus pulvinar risus quis feugiat commodo. Suspendisse rhoncus diam et viverra dignissim. Integer ac quam sed lectus eleifend volutpat.

fig.ii Sed consequat ante eget magna rhoncus ultricies laoreet sit amet odio. © Lorem Ipsum

images

figs.i,xii,xiii,xv,xvii,xxii Photograph of Ljubljana

© Will Jennings.

figs.ii,iii The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, Jakopič Promenade,

Sinzo Aanza, The Irregular Line, 2025. Photo: Jaka Babnik. MGLC

Archive.

figs.iv,v The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, MGLC Plečnik

Auditorium, Kathrin Siegrist, A Shade We Share I, 2025. Photo: Jaka Babnik.

MGLC Archive.

figs.vi-viii

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, MGLC Švicarija, Silvan

Omerzu, The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians, 2025. Photo: Jaka

Babnik. MGLC Archive.

fig.ix The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, Museum of Modern Art

(MG+), Kathrin Siegrist, A Shade We Share II, 2025. Photo: Riccardo

Buck.

fig.x

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, Museum of Modern Art

(MG+), Aili Vint, Meeting

place, 1990; Composition square by square, 1977. Photo: Jaka Babnik. MGLC

Archive.

fig.xi

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, Museum of Modern Art

(MG+), Aili Vint, Detail of the Sea, 1979. Photo: Jaka Babnik.

MGLC Archive.

fig.xiv The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of

Graphic Arts, Ljubljana Castle, "S" Gallery, Sreda v sredo. Photo: Klemen

Ilovar.

fig.xvi The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana Castle,

"S" Gallery, Sreda v sredo, Urban Cerjak, 300 μm (aquatint,

etching). Photo: courtesy of the artist. Photo: Urban Cerjak.

figs.xviii-xx Crafting Biodiversity: Biodiversity Parcels. Permit for phased mowing, 2025. Location: Public greenspace, Ljubljana. Artists: Trajna/Krater collective (Gaja Mežnarić Osole, Andrej Koruza), Debra Solomon. Photos: Amadeja

Smrekar

fig.xxi 35th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, From the void came gifts of the cosmos, 2023/2024, poster (design by Ajdin Bašić).

fig.xxiii 6th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana, 1965, poster (design by Ivan Picelj).

publication date

02 October 2025

tags

Sinzo Aanza, Žiga Artnak, Riccardo Buck, Urban Cerjak, Matic Flajs, Lorenzo Graf, Krater, Ljubljana, MAO, Chus Martínez, Svetlana Makarovič, Museum of Museum of Architecture and Design, Tejswini Narayan Sonawane, Silvan Omerzu, Ivan Picelj, Jože Plečnik, S Gallery, Kathrin Siegriest, Slovenia, Sreda v sredo, Vesna Teržan, The Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, Tivoli Castle, Aili Vint, Božidar Zrisnki

fig.ii Sed consequat ante eget magna rhoncus ultricies laoreet sit amet odio. © Lorem Ipsum