Ursula K. Le Guin’s speculative cartography

A recent exhibition at London’s Architectural Association presented

maps drawn by author Ursula K. Le Guin as part of her authorial worldbuilding process.

Sam Moore visited to explore her maps and drawings to think not only about the imaginary

places represented, but our own personal and collective relationships to the

world we inhabit.

In the short story On Exactitude in Science, Jorge

Luis Borges writes about a people who were dissatisfied with the already grand

scales of their ambitious cartography, wherein “the map of a single Province

occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire the entirety of a

Province.” The Cartographers Guild grew to think that maps of this size were

unable to capture the details of their lands, and so a map of the Empire was

created, one the size of the Empire itself.

Cartography has always had a speculative aspect to it; maps and globes and records of a land exist to tell a story of that land. Even the way in which we understand our own planet is informed by these things; where some maps distort the size of locations, the Peters Projection Map aims to show countries that are all correct in size, relative to one another. The map then, is a political document as much as anything else, something which echoes through the speculative cartography of author Ursula K. Le Guin.

![]()

![]()

![]()

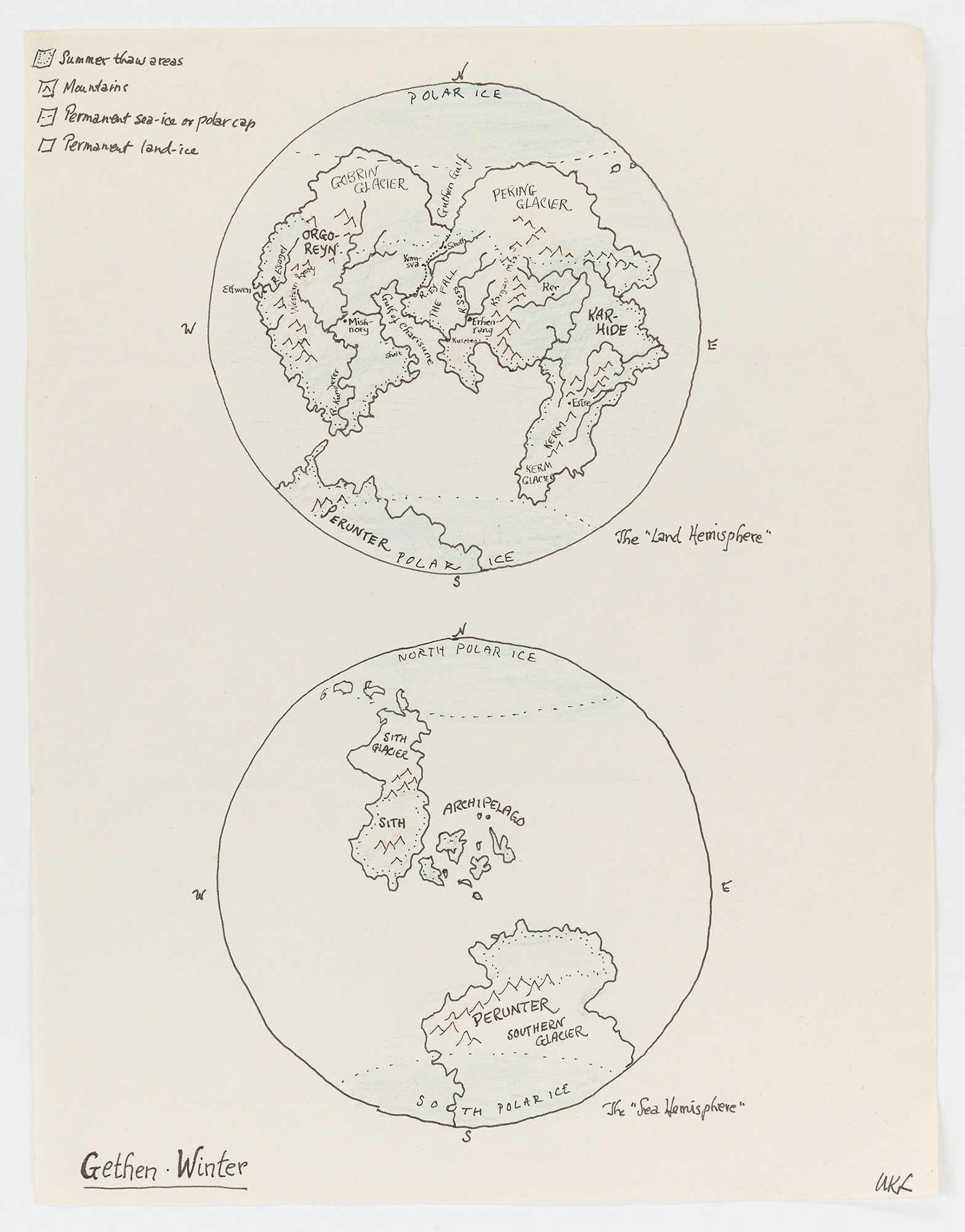

When Le Guin would begin writing a new story, she would draw a map of the world in which it would take place. Often, her characters would also engage in this kind of cartography; Tenar – protagonist of various novels, including some in Le Guin’s Earthsea series – is said to draw maps “at the scale of the spaces she knows,” which recalls Borges’ society creating a map of the Empire at the size of the Empire. But at the core of Le Guin’s map-making, not just in her process but in the stories themselves, is the role that it plays in exploring her imagined cultures, and the fragility that they often embody.

As an exhibition on Le Guin’s maps at London’s Architectural Association, The Word for World, reveals, the word is “Forest;” the name of a 1972 novel by Le Guin in which the peaceful Atheshe people are enslaved by colonisers from Terra. The forest itself, just like the map, is a fragile landmass and can be torn down, left with the imprint of colonisation upon it – which seeps into the world of Atheshe by the end of Le Guin’s novel.

![]()

![]()

![]()

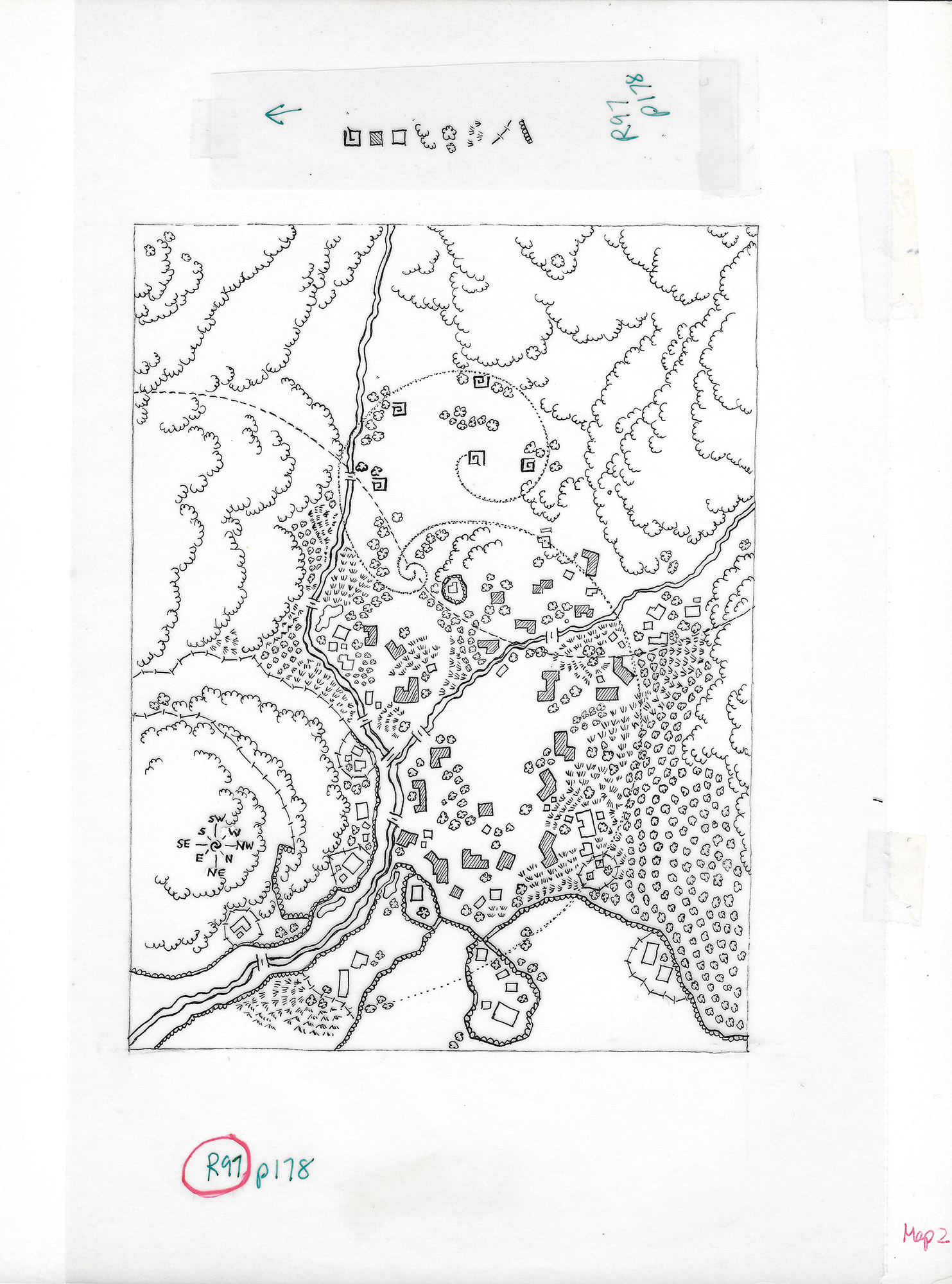

There’s a fluidity to the maps in Le Guin’s culture; not just in their fragile nature but in the language that they seem to embody. Always Coming Home, a 1985 book presented as an anthropological study of the Kesh people, follows their plight living in what was once Northern California as they almost recover from a climate catastrophe. The maps of the Kesh were described by Le Guin as “talismanic,” more interested in one’s place in the world than anything else. In Always Coming Home, the Kesh draw maps of the things that they already know well; less interested in charting out new and unexplored worlds, and more interested in developing an intimate relationship with the place that they call home.

Time itself is a part of the landscape of the novel, and maps are able to capture this. The visual language of Kesh maps, spirals and interlocking lines that show the river and the settlements that surround it, speak to the wider philosophy of the Kesh; in which spirals manifest the way that the Kesh relate to communities and home, to a sense of time that they don’t perceive as a direction. The maps of the rivers are drawn so that they flow downstream from the top to the bottom of the page, a mirror of the way water moves through the landscape.

![]()

![]()

![]()

For Le Guin as a writer, and for the civilisations that she brings to life, the landscape comes first and the map seems to come second; a stark contrast to the ways in which we might understand the cartography of colonisation, wherein a blank space is filled in by a people that trample the worlds that they discover underfoot. But neither the maps, nor the landscapes themselves, are permanent in these novels. Always Coming Home exists in the aftermath of a climate catastrophe and the Ashte people are changed by a colonising force.

There’s a tension in Le Guin’s landscapes; they always seem able to outlast the people who inhabit them, even if they’re never able to survive in one form for long. Early on in Always Coming Home, she rapturously describes the flowers, plants, and winding paths of the Valley. “The roots of the valley are in wildness, in dreaming, in dying, in eternity. The deer trails there, the footpaths and the wagon tracks, they pick their way around the root of things. They don’t go straight. It can take a lifetime to go thirty miles, and come back.” Our own maps are so often made up of straight lines, of declarative borders and stark divisions – it’s tempting to think of the almost comically, ruler-drawn straight line at the top of Texas on an American map – and for Le Guin, to do so seems to be not just a disservice to the landscape, but to the people.

![]()

![]()

![]()

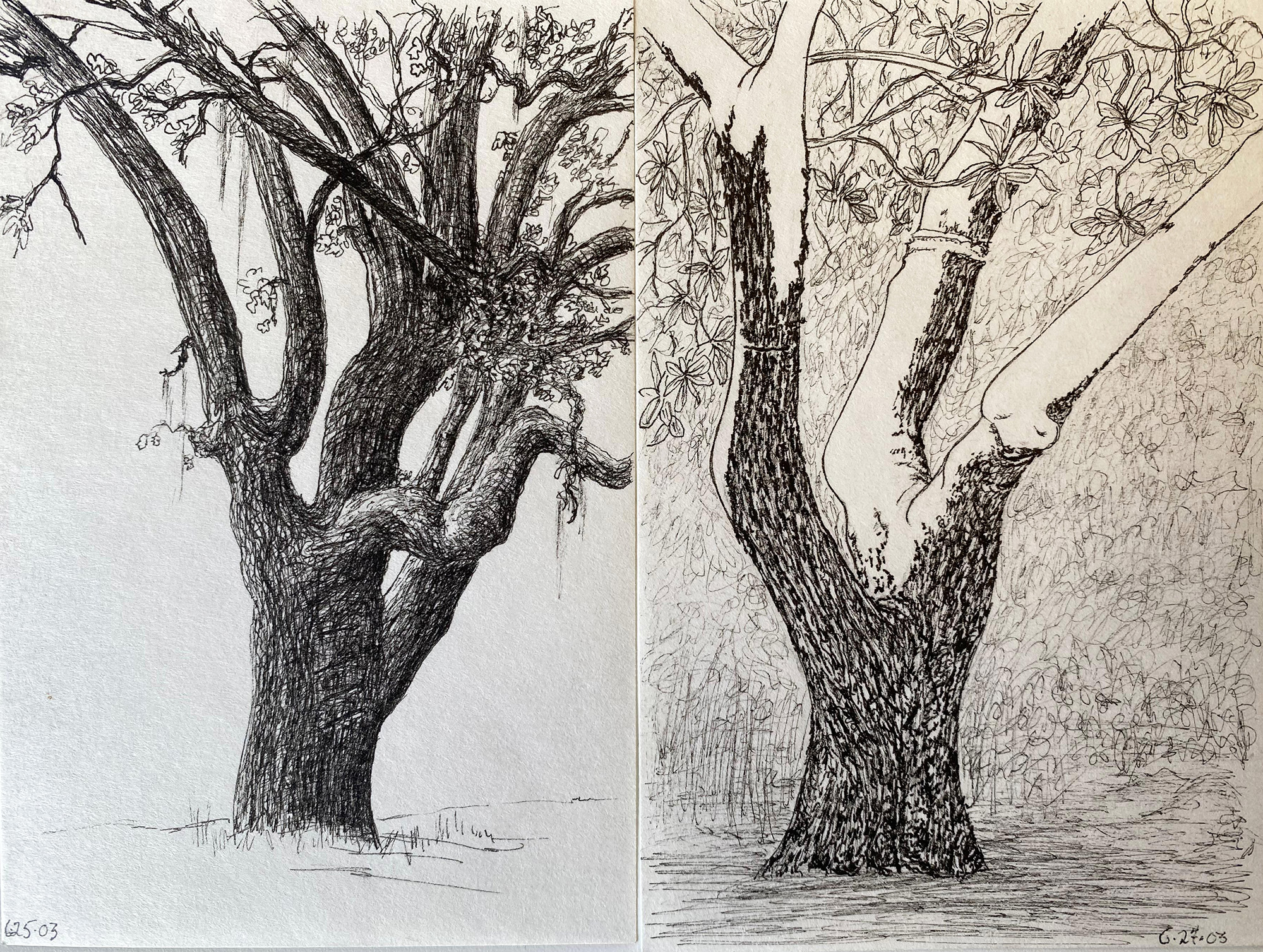

It’s tempting to think of maps – of literature, of history, of all the things that Le Guin excavates in Always Coming Home – as being permanent because they’ve been written down. But these speculative maps refuse to gesture towards the permanent or the objective. Some of their power comes from the fact that they’re so willing to lean into the subjective languages and philosophies of Le Guin’s worlds and civilisations. Throughout The Word for World, some of Le Guin’s own drawings and paintings are placed next to the maps in her novels; an untitled pastel on paper, an undated pencil drawing of Haystack Rock in Oregon are on the wall next to a map of some of the paths around Sinshan Creek in Always Coming Home. Le Guin’s own drawings seem to challenge the ways in which we might typically understand landscapes; her drawing of Haystack Rock presents the eponymous feature in the distance, almost abstract and monolithic, while her pastel of the waves is closer to abstraction than anything else.

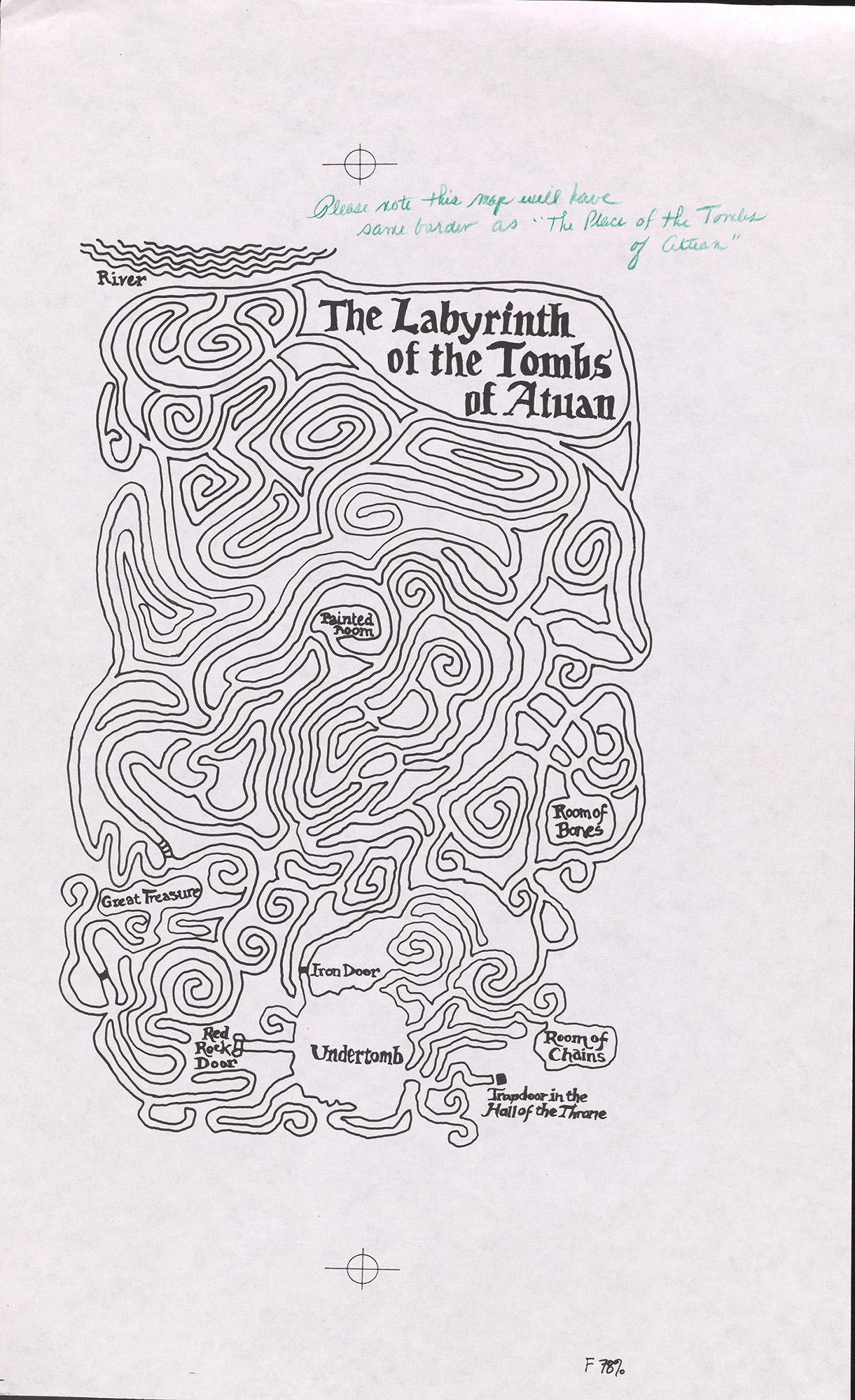

It’s no wonder that her speculative maps care more for the roads on which people travel than the objects and landmarks they might find. The map of the Labyrinth of the Tombs of Atuan, drawn by Tenar, is itself labyrinthine, a maze that one can get lost in simply by looking at it; the labyrinth is not a place to be conquered then, or scarcely even a place to be navigated (there are some circles for the Undertomb, Great Fissure, and Room of Bones, but no detailed capturing of their features), but instead a space to be understood through the ways in which one might move through it. These drawings seem to ask that, rather than capturing the minutiae of a place whatever the cost may be, that what matters most in how we understand a landscape is the way in which we move through it; that to put this down on paper is not to put down any universal or objective truth, but our own, ever-changing relationship with the world itself.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cartography has always had a speculative aspect to it; maps and globes and records of a land exist to tell a story of that land. Even the way in which we understand our own planet is informed by these things; where some maps distort the size of locations, the Peters Projection Map aims to show countries that are all correct in size, relative to one another. The map then, is a political document as much as anything else, something which echoes through the speculative cartography of author Ursula K. Le Guin.

figs.i-iii

When Le Guin would begin writing a new story, she would draw a map of the world in which it would take place. Often, her characters would also engage in this kind of cartography; Tenar – protagonist of various novels, including some in Le Guin’s Earthsea series – is said to draw maps “at the scale of the spaces she knows,” which recalls Borges’ society creating a map of the Empire at the size of the Empire. But at the core of Le Guin’s map-making, not just in her process but in the stories themselves, is the role that it plays in exploring her imagined cultures, and the fragility that they often embody.

As an exhibition on Le Guin’s maps at London’s Architectural Association, The Word for World, reveals, the word is “Forest;” the name of a 1972 novel by Le Guin in which the peaceful Atheshe people are enslaved by colonisers from Terra. The forest itself, just like the map, is a fragile landmass and can be torn down, left with the imprint of colonisation upon it – which seeps into the world of Atheshe by the end of Le Guin’s novel.

figs.iv-vi

There’s a fluidity to the maps in Le Guin’s culture; not just in their fragile nature but in the language that they seem to embody. Always Coming Home, a 1985 book presented as an anthropological study of the Kesh people, follows their plight living in what was once Northern California as they almost recover from a climate catastrophe. The maps of the Kesh were described by Le Guin as “talismanic,” more interested in one’s place in the world than anything else. In Always Coming Home, the Kesh draw maps of the things that they already know well; less interested in charting out new and unexplored worlds, and more interested in developing an intimate relationship with the place that they call home.

Time itself is a part of the landscape of the novel, and maps are able to capture this. The visual language of Kesh maps, spirals and interlocking lines that show the river and the settlements that surround it, speak to the wider philosophy of the Kesh; in which spirals manifest the way that the Kesh relate to communities and home, to a sense of time that they don’t perceive as a direction. The maps of the rivers are drawn so that they flow downstream from the top to the bottom of the page, a mirror of the way water moves through the landscape.

figs.vii-ix

For Le Guin as a writer, and for the civilisations that she brings to life, the landscape comes first and the map seems to come second; a stark contrast to the ways in which we might understand the cartography of colonisation, wherein a blank space is filled in by a people that trample the worlds that they discover underfoot. But neither the maps, nor the landscapes themselves, are permanent in these novels. Always Coming Home exists in the aftermath of a climate catastrophe and the Ashte people are changed by a colonising force.

There’s a tension in Le Guin’s landscapes; they always seem able to outlast the people who inhabit them, even if they’re never able to survive in one form for long. Early on in Always Coming Home, she rapturously describes the flowers, plants, and winding paths of the Valley. “The roots of the valley are in wildness, in dreaming, in dying, in eternity. The deer trails there, the footpaths and the wagon tracks, they pick their way around the root of things. They don’t go straight. It can take a lifetime to go thirty miles, and come back.” Our own maps are so often made up of straight lines, of declarative borders and stark divisions – it’s tempting to think of the almost comically, ruler-drawn straight line at the top of Texas on an American map – and for Le Guin, to do so seems to be not just a disservice to the landscape, but to the people.

figs.x-xii

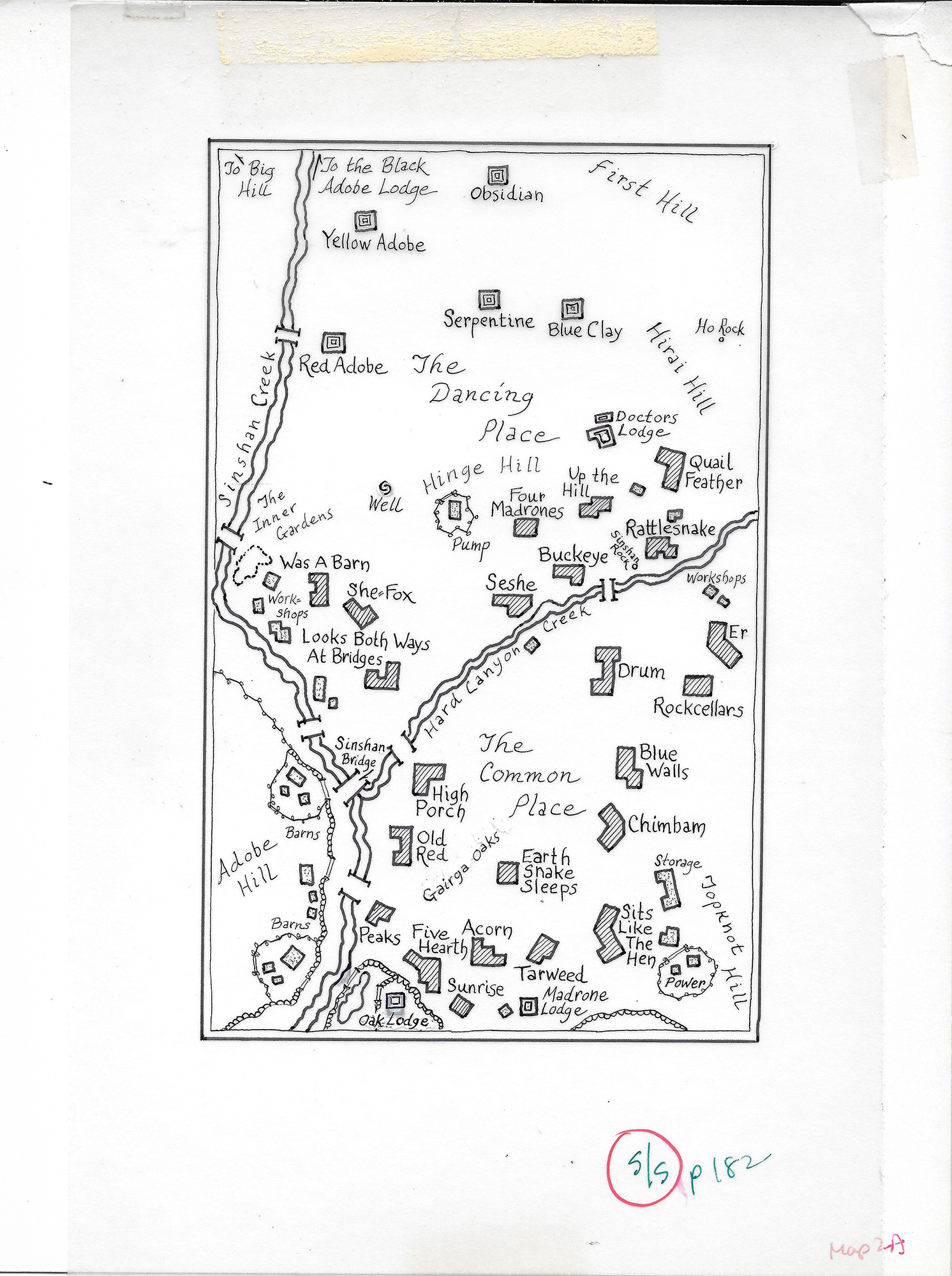

It’s tempting to think of maps – of literature, of history, of all the things that Le Guin excavates in Always Coming Home – as being permanent because they’ve been written down. But these speculative maps refuse to gesture towards the permanent or the objective. Some of their power comes from the fact that they’re so willing to lean into the subjective languages and philosophies of Le Guin’s worlds and civilisations. Throughout The Word for World, some of Le Guin’s own drawings and paintings are placed next to the maps in her novels; an untitled pastel on paper, an undated pencil drawing of Haystack Rock in Oregon are on the wall next to a map of some of the paths around Sinshan Creek in Always Coming Home. Le Guin’s own drawings seem to challenge the ways in which we might typically understand landscapes; her drawing of Haystack Rock presents the eponymous feature in the distance, almost abstract and monolithic, while her pastel of the waves is closer to abstraction than anything else.

It’s no wonder that her speculative maps care more for the roads on which people travel than the objects and landmarks they might find. The map of the Labyrinth of the Tombs of Atuan, drawn by Tenar, is itself labyrinthine, a maze that one can get lost in simply by looking at it; the labyrinth is not a place to be conquered then, or scarcely even a place to be navigated (there are some circles for the Undertomb, Great Fissure, and Room of Bones, but no detailed capturing of their features), but instead a space to be understood through the ways in which one might move through it. These drawings seem to ask that, rather than capturing the minutiae of a place whatever the cost may be, that what matters most in how we understand a landscape is the way in which we move through it; that to put this down on paper is not to put down any universal or objective truth, but our own, ever-changing relationship with the world itself.

figs.xiii-xv

Ursula K Le Guin (1929–2018) was the celebrated

author of twenty-one novels, eleven volumes of short stories, four collections

of essays, twelve children’s books, six volumes of poetry and four of

translation. The breadth and imagination of her work earned her six Nebulas,

nine Hugos and SFWA’s Grand Master, along with the PEN/ Malamud and many other

awards. In 2014 she was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for

Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, and in 2016 joined the short

list of authors to be published in their lifetimes by the Library of America.

www.ursulakleguin.com

The Architectural Association (AA) is the oldest

school of architecture in the UK; it was founded in 1847 as a student-centred

collective that aspired to radically transform architectural education. The

school offers a broad range of flexible, self-directed programmes, courses and

curricula that empower students and staff to challenge the accepted methods

within contemporary architectural education and professional practice. These

are enhanced by the Public Programme, which focuses on the unique opportunities

and challenges of the present through a series of lectures, exhibitions, studio

visits, symposia and book launches, and by the Communications Studio, a media,

publishing and graphic design studio. The school offers a Foundation Award, a

BA(Hons)/RIBA Part 1 and MArch/RIBA Part 2 (and AA Diploma) throughout its

five-year course within the Intermediate and Diploma Programmes, and ten Taught

Postgraduate programmes as well as the PhD Programme, a RIBA-accredited Part 3

course, a Summer School and Visiting Schools based around the world.

www.aaschool.ac.uk

Sam Moore is a writer and editor. They are the

author of All my teachers died of AIDS (Pilot Press, 2020), and Long live the

new flesh (2022). Their criticism has been published by Frieze, The FT, The

Guardian, Hyperallergic, and more. They are one of the co-curators of TISSUE, a

trans reading series based in London.

www.aaschool.ac.uk

Sam Moore is a writer and editor. They are the

author of All my teachers died of AIDS (Pilot Press, 2020), and Long live the

new flesh (2022). Their criticism has been published by Frieze, The FT, The

Guardian, Hyperallergic, and more. They are one of the co-curators of TISSUE, a

trans reading series based in London.

info

The Word for World, an exhibition curated by Sarah

Shin with AA Public Programme, presenting the maps of Ursula K Le Guin was

presented at the Architectural Association, London, 10 October to 06 December

2025.

Further information is available at: www.aaschool.ac.uk/publicprogramme/whatson/the-word-for-world

A book of the same title is co-published by Spiral House

& AA Publications and is available from the AA Bookshop, details here: www.bookshop.aaschool.ac.uk/?product=the-word-for-world

images

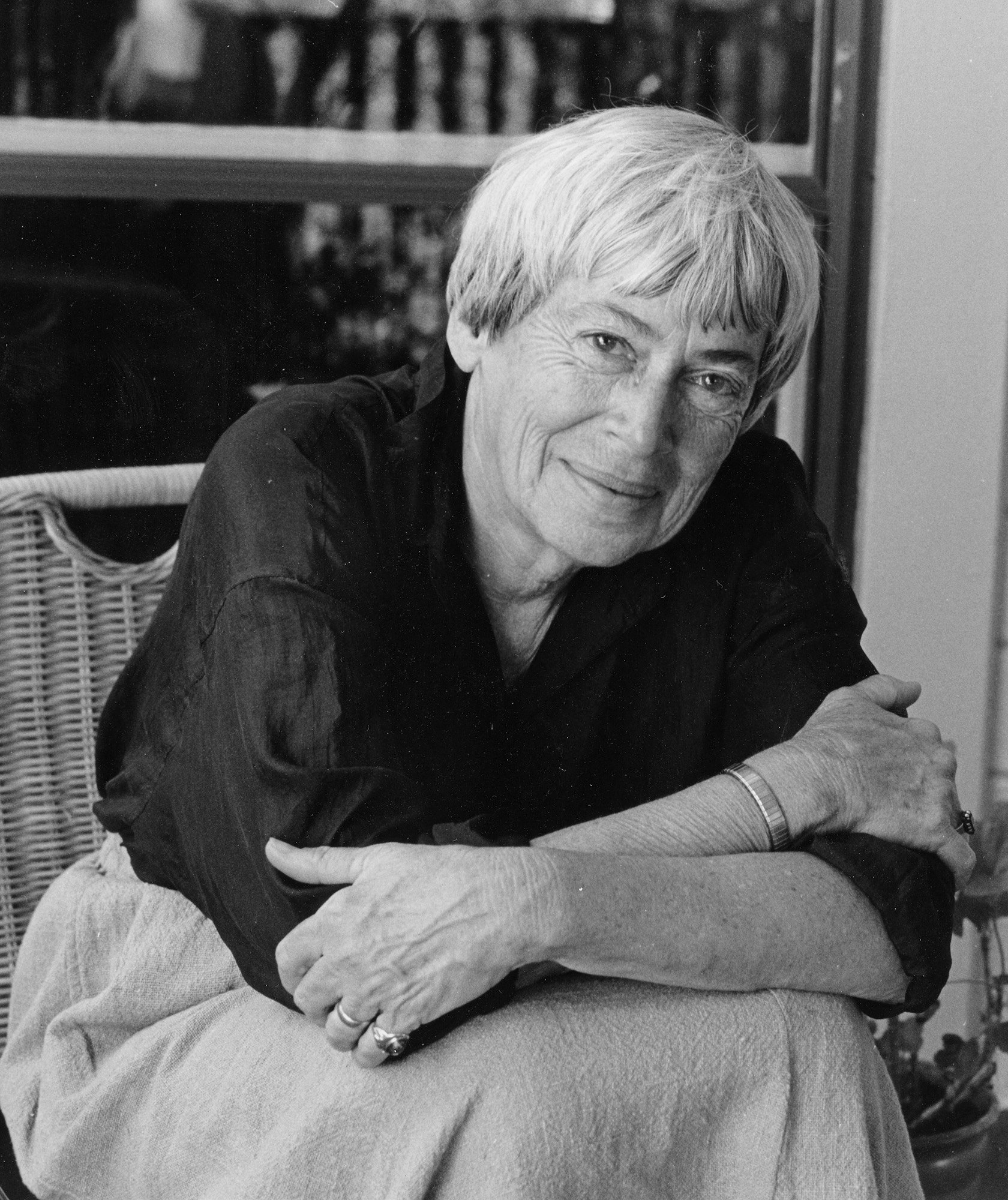

fig.i Portrait of Ursula K Le Guin, courtesy

Ursula K Le Guin Foundation.

figs.ii,v,viii,xi,xiv The Word For World at the Architectural Association. Photographs

©

Elena Andreea Teleaga.

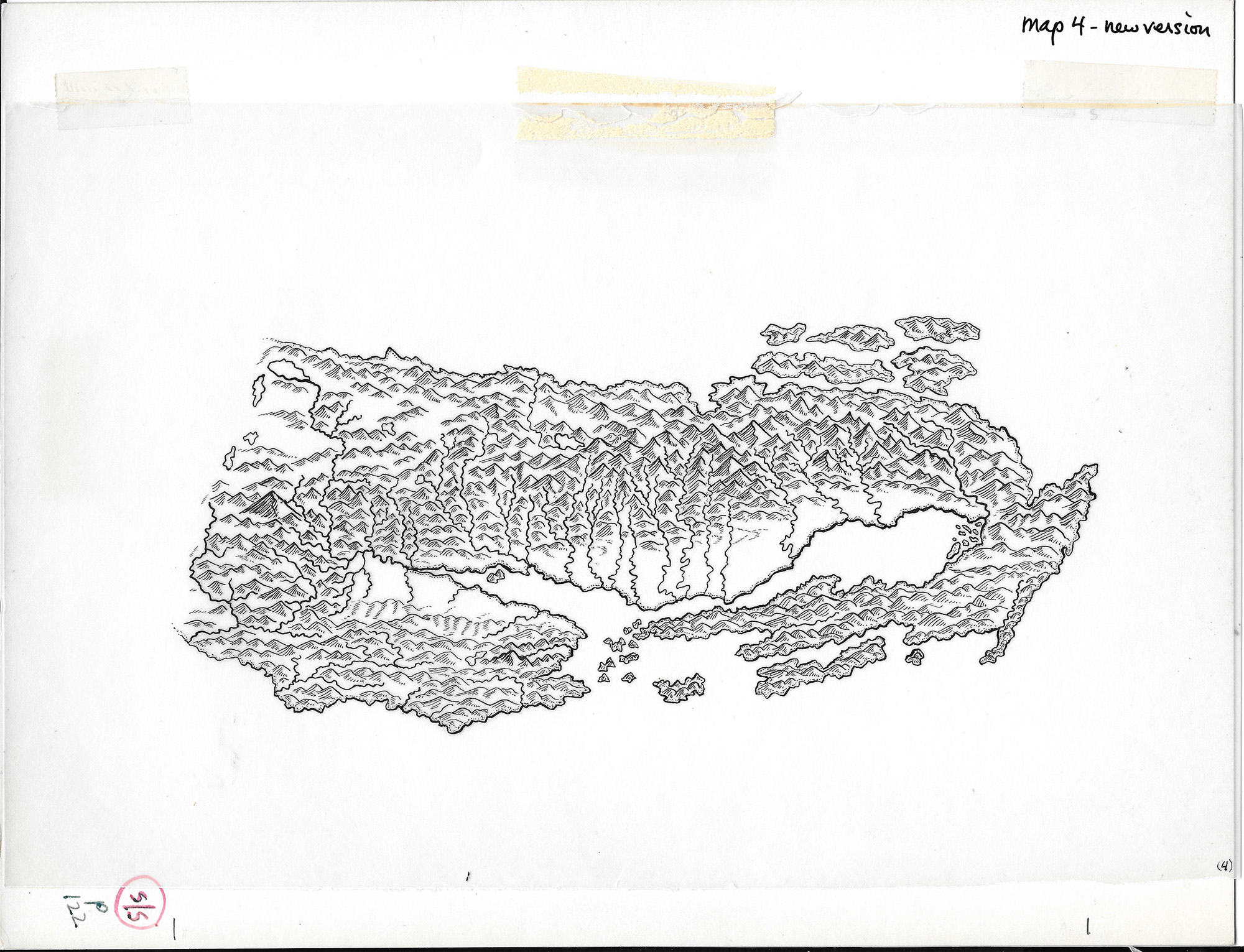

fig.iii Hemispheres of Gethen, unpublished, for The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969. Ink on typewriter paper. Courtesy Ursula K. Le Guin Foundation.

fig.iv

The

Town of Sinshan, 1985. Ink on paper. Courtesy Ursula K Le Guin Foundation.

fig.vi Untitled, 6-27-03 & Untitled, 6-25-03. Both ink on paper. Courtesy Ursula K. Le Guin Foundation

fig.vii

Rivers

that run into the Inland Sea, 1985, Ink on paper. Courtesy Ursula K Le Guin

Foundation.

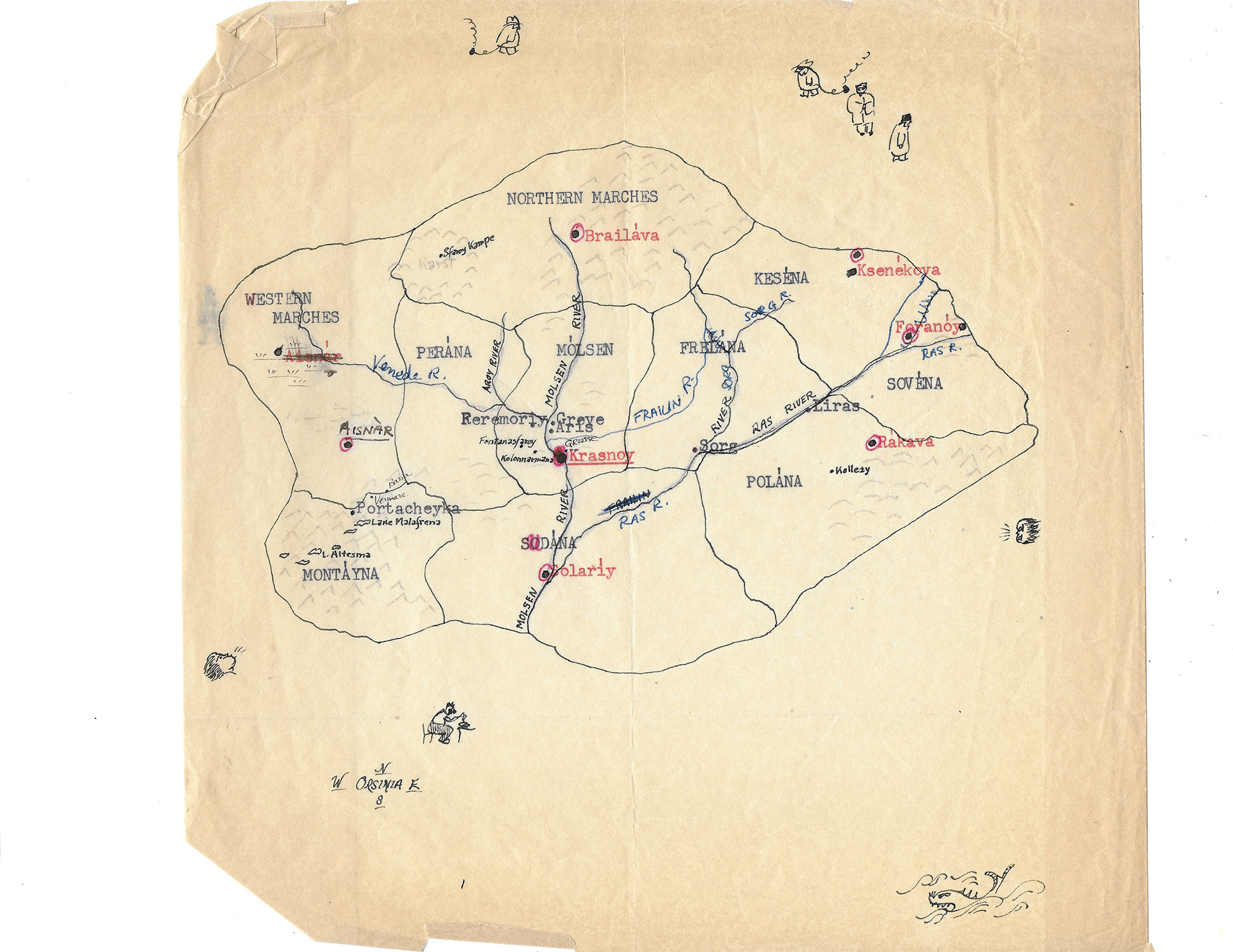

fig.ix Orsinia, the Ten Provinces, unpublished, for Malafrena, 1979. Ink and typewriter text on tracing paper. Courtesy Ursula K. Le Guin Foundation.

fig.x

Draft

for the Labyrinth of the Tombs of Atuan, with note, c.1970. Ink on paper. Courtesy

University of Oregon Libraries and Ursula K Le Guin Foundation.

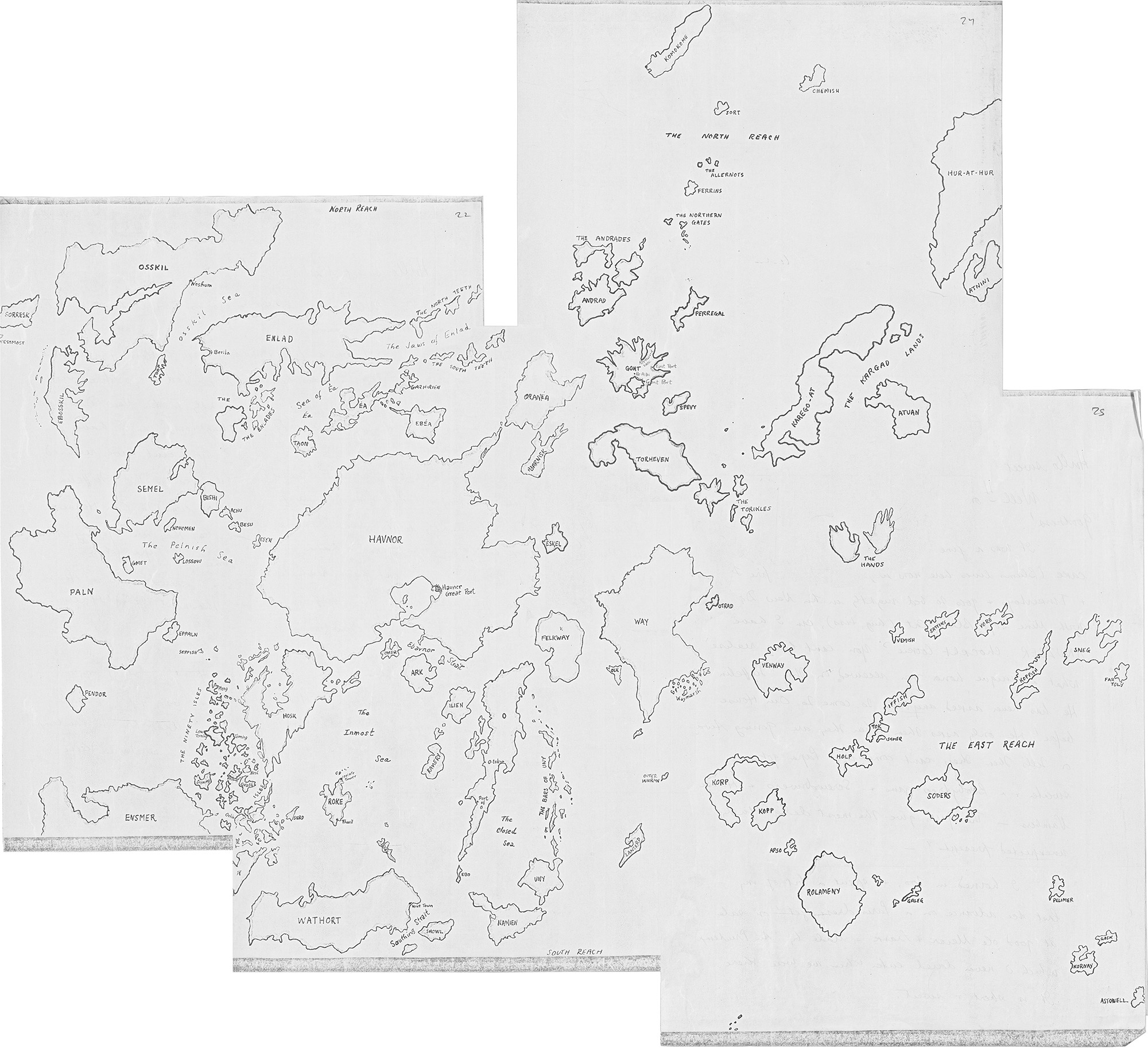

fig.xii

Central and Western Earthsea, For A Wizard of Earthsea,

c.1967. Ink on paper. Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries and Ursula K Le

Guin Foundation.

fig.xiii

The

Names of the Houses of Sinshan, 1985. Ink on paper. Courtesy Ursula K Le Guin

Foundation.

fig.xv England 75-76 (recollected or imagined). Watercolor or gouache on paper.

Courtesy Ursula K. Le Guin Foundation

publication date

15 January 2026

tags

AA, Architectural Association, Jorge Luis Borges, Ursula K Le Guin, Maps, Sam Moore

Further information is available at: www.aaschool.ac.uk/publicprogramme/whatson/the-word-for-world

A book of the same title is co-published by Spiral House & AA Publications and is available from the AA Bookshop, details here: www.bookshop.aaschool.ac.uk/?product=the-word-for-world