At Edinburgh’s RSA, architect Richard Murphy looks at the generational

family tree of design

At the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh, celebrated

architect Richard Murphy OBE has curated a show considering the legacy &

flow of ideas through the family tree of architecture. Drawing from his own

experiences with four seminal figures in the sector, Murphy then platforms young

practices opened by former employees of his own firm to search for paths of creativity

through time.

The cliché of an architecture exhibition is true. Too

often, it is about a singular genius, usually white and male, who has generously

offered his marvellous creations to the world. Often accompanied by images of

the celebrated architect towering over a model of their masterplan or

sculptural project, such monographic, monolithic narrative belies what is

really one of the most convoluted and complicated of all the arts. The building

– whether that be house, civic structure, museum, or whatever – rarely comes

from singular genius but from not only an office of (often badly paid) workers,

but a complex ecology of idea, inspiration, and learning.

That “no idea is new” is often repeated, but probably true in an occupation rooted in an idea of relentless creation of big shiny new things that is really rooted in visiting, looking, learning, borrowing, and improving. Exhibitions and publications that put the singular object upon a pedestal, as if conjured from nowhere with no reference to any history or context, do a disservice to a trade rooted in craft and collaboration.

A new exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh tries to push back against that cliché. Curated by Richard Murphy, an English architect based in Edinburgh over four decades, it seeks to acknowledge and celebrate the family tree which any singular architect finds themselves entangled within the branches of.

![]()

Richard Murphy RSA OBE is an architect widely recognised, including when he won the 2016 RIBA House of the Year for his own home in Edinburgh (which can be recognised by the regular international visitors and architectural photographers taking photos outside). But the exhibition Generation isn’t about his practice. Or, rather, it is about his practice if you consider the role of an architect not only one of making buildings, but also of making ideas, connections, stories, and legacy.

Murphy has selected a coterie of architects who have worked under him and for his eponymous practice, offering up space at the RSA to put their own projects on display – space he could have used for a monographic celebration of his own work is instead given to the next generation to promote theirs. Generation takes place at the start of the RSA’s bicentenary year celebrating Scottish art and architecture, and Murphy believes it is important to mark it by looking forwards as well as to history as part of that process.

“I was working for Richard MacCormack in London,” Murphy says, “and he came in one morning – he'd been to Ted Cullinan’s house for dinner the night before. Denys Lasdun was there and Ted introduced him to everyone as ‘my architectural dad.’ That got me thinking – I have got three dads, plus one posthumous dad! If you're an architect, you're interested in everything and everybody, but there are some people you've worked alongside that you feel have very strongly influenced you.”

![]()

![]()

These three+1 dads are introduced by Murphy in a short text mounted a triangular structure at the centre of the gallery. Alongside the aforementioned Ted Cullinan and Richard MacCormac are Isi Metzstein, who taught architecture at the University of Edinburgh and introduced Murphy to the RSA and the ‘posthumous dad’, legendary architect Carlo Scarpa, who Murphy never met, but has widely researched and written about.

The four are posited as the dads who gave Murphy the aesthetic and pedagogical framework he has lived by, and which he thinks may also be found within the architects present here on the RSA walls. This dedication to citation, referencing, and the baton-passing of creative knowledge is to be admired. In part, it comes from rich experiences in teaching alongside practicing. Murphy worked for several years under Metzstein teaching the next generation and has also worked in practices before leaving to create his own firm, and then employed several people who have followed the same path.

It seems that Murphy’s three decades of employees have had a better experience than he did briefly working under Will Alsop – “I quite quickly realised that Will and I were not going to get on. And I thought he was a little bit dick, actually” – though the experience did lead him to resign and start his own company with a colleague, having won a small competition for a restaurant, and perhaps be an easier-to-work-with boss.

Despite what clichés suggest, life as an architect is not always as empowering or celebratory as may be thought. It can be a slog. This was the case for Murphy: “We set up with that one job, on emergency rations. Two years later, we were still on emergency rations, so much. Then we got the Fruitmarket Gallery, but I think our total fee was only £30,000.” Juggling these small (yet impactful – the Fruitmarket is still one of Britain’s leading arts centres) projects alongside teaching, led Murphy to further understand that baton being passed down: “Oliver Chapman was the first student I employed. I was mostly teaching, so he was in the office five days a week, dealing with the office. Eventually he set up his own practice, and he’s included in this show. He died in 2024, which was really sad, but is represented here… his office is now run by a guy called Martin Lambie, also one of my ex-employees. It’s quite nice to keep it all in the family.”

A sentimental story, but also key to this exhibition. Evidently, Chapman’s experiences were important to the early 90’s origins of Richard Murphy Architects (RMA), but also this idea of recognition and shared experiences – as well as perhaps Chapman’s untimely passing – seem formative to Murphy’s thinking on the entangled architectural family tree presented.

For Generation, Murphy didn’t select every ex-employee who set up their own firm but an edited selection. “The RSA exhibitions committee told me ‘you still have to curate it, it cannot just be an open house for people who worked for you…’ and I get that, because there have been people in my office who've gone off, set up their own office, and done crap mundane stuff.” Joking that the collective noun for a group of architects should be termed “a jealousy” Murphy acknowledges that some who worked under him might be angry at getting no invitation to take part: “That's inevitable, I'll just say there wasn't space.”

![]()

![]()

So, what are the connections made here between boss/curator and employee/exhibitor? Each invitee is given a space of wall to present their firm’s work alongside a short information panel which, handily, highlights with images a couple of projects they worked on with Murphy before heading off on their own. The curation is not didactic, and any cohesive narrative is really left up to the visitor to infer, though there are some clues here: Kris Grant worked for Murphy on the Dunfermline Carnegie Library & Galleries in Fife which has an aesthetic conversation with the two garden pavilions he designed and presents here; and Weiz Train and Bus Stations in Austria by Jordi Sanahuja i Vidal have a dramaturgy reflected on in the architects’ reminiscing of his one year working at RMA.

“I think all of them subscribe to the point of view that you can do potentially radical things with historic buildings,” Murphy observes of his selection, “and secondly, I think they all have got a very strong social idea about what architecture is, about how it works, about people – and you wouldn't get that if you're working at Zaha Hadid’s office, for example, where it's all about sculptural form.”

In other contributors’ displays, direct lineage is less visible, though their texts discuss approaches carried on from Richard Murphy Architects into their own work, of rooflights, materials, detailing, and floorplans. “There are probably too many words in the exhibition,” Murphy says. There are a lot, though the issue is less the amount of words (which are, rarely for an architecture exhibition, written without jargon or overly-academic flourishes) but more that they have to do the curatorial work where curation and exhibition do not.

![]()

Murphy spent four years working under Metzstein at the University of Edinburgh. While he then had no time for designing, it did give him the space to explore and research Carlo Scarpa, publishing his first of three books on the architect in 1990. “Then I looked at all my fellow teachers and I thought ‘shit, if I don't get out now I will turn into one of them!’ I wasn't doing any building and I don't think students respect you if you don't build, or if you haven't built – it’s a bit like having a piano teacher who never plays the piano.”

Since leaving academia, Murphy has designed many buildings, including several for the cultural sector – including Perth Theatre, the British Golf Museum, Dundee Contemporary Arts, and ongoing plans for the Scottish National Centre for Music. This doesn’t mean, however, that the architect reaches far beyond the silo of architecture, its canon, and modes of representation and discourse in his work.

“There are a lot of people trying to twist my arm to become president of the RSA,” he says, but is quick to add that “the trouble is, I don't know enough about art! People would find me out – ‘Don't worry about that, you're an architect, you're not expected to know about art,’ they say, but if you ask me to name ten living Scottish artists I’d struggle.” Murphy’s extra-curricular culture is mainly in music, including singing in the Scottish Chamber Orchestra choir.

![]()

![]()

![]()

There is generosity in the intent of Generation. Murphy recognises that his practice’s work expanded on and riffed off ideas from the likes of Scarpa, Cullinan, and MacCormac. “There's no question that the stuff I do is a consequence of their work,” he says, and wanting to “skip a generation” to then follow that family tree to those who worked under him is potentially interesting – even if he is still the focus of the exhibition through acting as the generational conduit and glowingly discussed in the participants’ texts.

The exhibition, however, needs a curator who is not situated at the centre of that story, and it needs to explore in and around the subject in a more curious, creative, and engaging way than solely using panels of text and photographs. Murphy’s lack of interest in art, exhibitions, and wider modes of cultural representation beyond traditional architectural pin-ups is very present and there is perhaps a missed opportunity by not introducing external eye looking in, critically, upon such a premise of the family tree as a pathway of idea and approach.

![]()

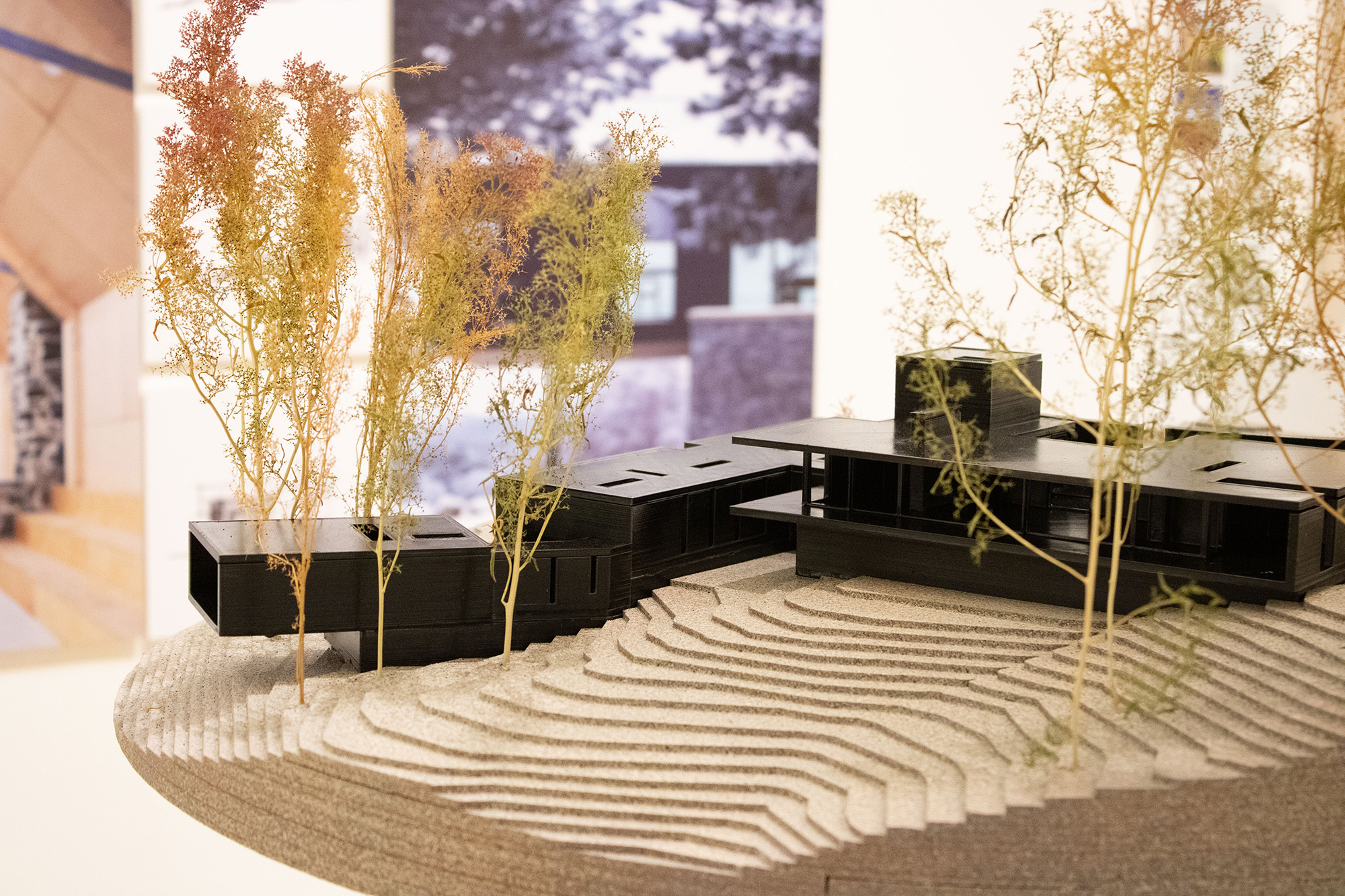

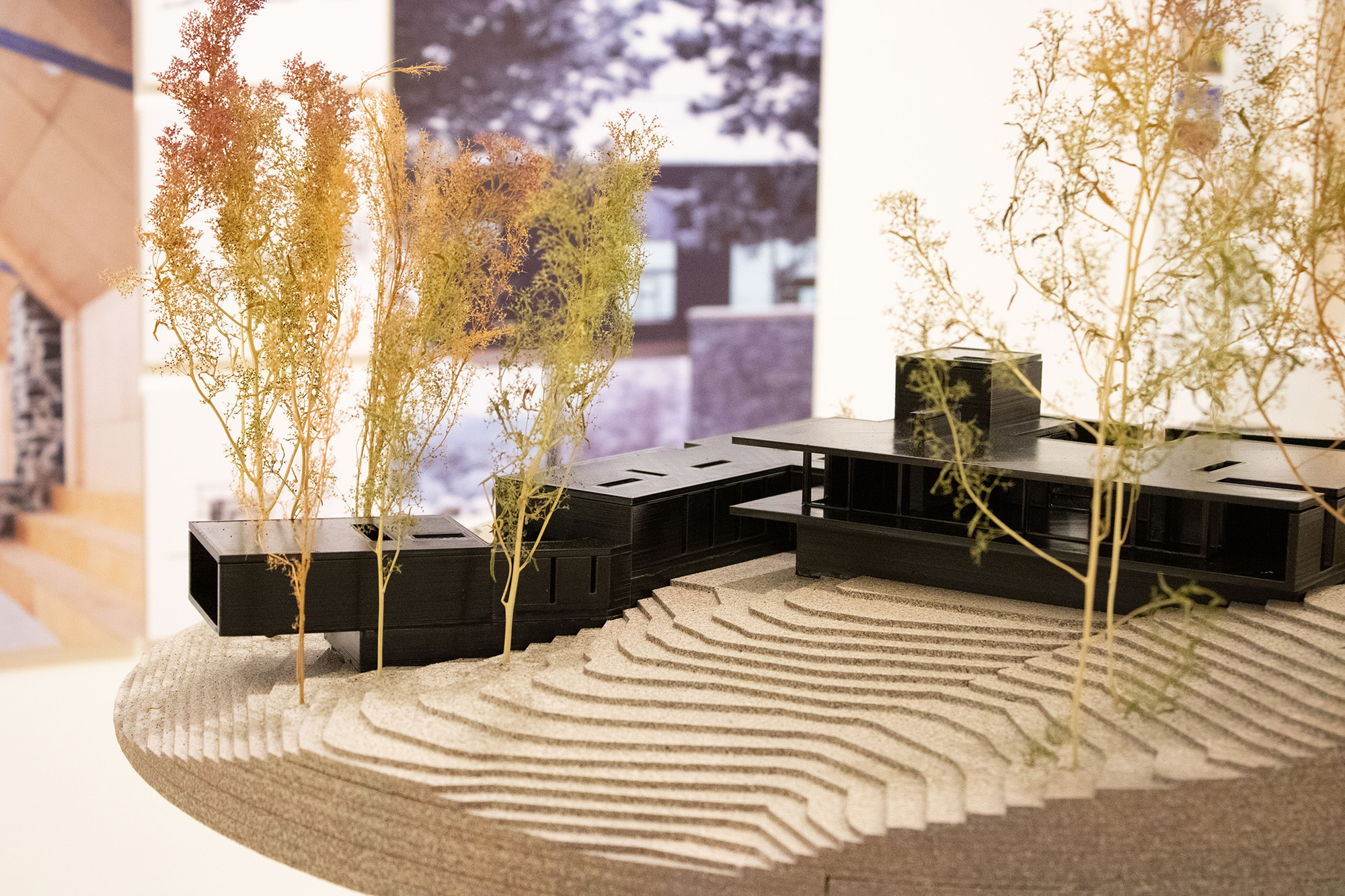

fig.x

There are design ideas that flow from Scarpa and Cullinan, through Murphy and then to another generation, and there are also pedagogical and theoretical ideas that also descend. There is also plenty of scope for exhibitions about architecture that de-centre the craft away from narratives of the singular genius towards ideas of shared making, re-making, learning, and lending. However, by essentially acting as a promotional platform for a few young architect practices, leaning in on the tired (and inaccessible to most visitors) curatorial approach of plans, photos, and text on panels, and by being solely made by the very people the exhibition considers, Generation misses that opportunity.

Just as one may criticise architectural educators who do not practice architecture failing to understand the medium they teach, so too there may be a lesson here about architects making exhibitions who similarly do not understand the medium or art of curation. There is an interesting exhibition to be made about how ideas and aesthetic sinuously travel through designs, research, education, and studio, and such a project could easily root itself in a city such as Edinburgh, using architectural history, present, and future. Such an exhibition could easily use RMA’s built and speculative projects for the city as well as Richard Murphy’s research on Scarpa to explore such a generational sharing of knowledge.

That “no idea is new” is often repeated, but probably true in an occupation rooted in an idea of relentless creation of big shiny new things that is really rooted in visiting, looking, learning, borrowing, and improving. Exhibitions and publications that put the singular object upon a pedestal, as if conjured from nowhere with no reference to any history or context, do a disservice to a trade rooted in craft and collaboration.

A new exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh tries to push back against that cliché. Curated by Richard Murphy, an English architect based in Edinburgh over four decades, it seeks to acknowledge and celebrate the family tree which any singular architect finds themselves entangled within the branches of.

fig.i

Richard Murphy RSA OBE is an architect widely recognised, including when he won the 2016 RIBA House of the Year for his own home in Edinburgh (which can be recognised by the regular international visitors and architectural photographers taking photos outside). But the exhibition Generation isn’t about his practice. Or, rather, it is about his practice if you consider the role of an architect not only one of making buildings, but also of making ideas, connections, stories, and legacy.

Murphy has selected a coterie of architects who have worked under him and for his eponymous practice, offering up space at the RSA to put their own projects on display – space he could have used for a monographic celebration of his own work is instead given to the next generation to promote theirs. Generation takes place at the start of the RSA’s bicentenary year celebrating Scottish art and architecture, and Murphy believes it is important to mark it by looking forwards as well as to history as part of that process.

“I was working for Richard MacCormack in London,” Murphy says, “and he came in one morning – he'd been to Ted Cullinan’s house for dinner the night before. Denys Lasdun was there and Ted introduced him to everyone as ‘my architectural dad.’ That got me thinking – I have got three dads, plus one posthumous dad! If you're an architect, you're interested in everything and everybody, but there are some people you've worked alongside that you feel have very strongly influenced you.”

figs.ii,iii

These three+1 dads are introduced by Murphy in a short text mounted a triangular structure at the centre of the gallery. Alongside the aforementioned Ted Cullinan and Richard MacCormac are Isi Metzstein, who taught architecture at the University of Edinburgh and introduced Murphy to the RSA and the ‘posthumous dad’, legendary architect Carlo Scarpa, who Murphy never met, but has widely researched and written about.

The four are posited as the dads who gave Murphy the aesthetic and pedagogical framework he has lived by, and which he thinks may also be found within the architects present here on the RSA walls. This dedication to citation, referencing, and the baton-passing of creative knowledge is to be admired. In part, it comes from rich experiences in teaching alongside practicing. Murphy worked for several years under Metzstein teaching the next generation and has also worked in practices before leaving to create his own firm, and then employed several people who have followed the same path.

It seems that Murphy’s three decades of employees have had a better experience than he did briefly working under Will Alsop – “I quite quickly realised that Will and I were not going to get on. And I thought he was a little bit dick, actually” – though the experience did lead him to resign and start his own company with a colleague, having won a small competition for a restaurant, and perhaps be an easier-to-work-with boss.

Despite what clichés suggest, life as an architect is not always as empowering or celebratory as may be thought. It can be a slog. This was the case for Murphy: “We set up with that one job, on emergency rations. Two years later, we were still on emergency rations, so much. Then we got the Fruitmarket Gallery, but I think our total fee was only £30,000.” Juggling these small (yet impactful – the Fruitmarket is still one of Britain’s leading arts centres) projects alongside teaching, led Murphy to further understand that baton being passed down: “Oliver Chapman was the first student I employed. I was mostly teaching, so he was in the office five days a week, dealing with the office. Eventually he set up his own practice, and he’s included in this show. He died in 2024, which was really sad, but is represented here… his office is now run by a guy called Martin Lambie, also one of my ex-employees. It’s quite nice to keep it all in the family.”

A sentimental story, but also key to this exhibition. Evidently, Chapman’s experiences were important to the early 90’s origins of Richard Murphy Architects (RMA), but also this idea of recognition and shared experiences – as well as perhaps Chapman’s untimely passing – seem formative to Murphy’s thinking on the entangled architectural family tree presented.

For Generation, Murphy didn’t select every ex-employee who set up their own firm but an edited selection. “The RSA exhibitions committee told me ‘you still have to curate it, it cannot just be an open house for people who worked for you…’ and I get that, because there have been people in my office who've gone off, set up their own office, and done crap mundane stuff.” Joking that the collective noun for a group of architects should be termed “a jealousy” Murphy acknowledges that some who worked under him might be angry at getting no invitation to take part: “That's inevitable, I'll just say there wasn't space.”

figs.iv,v

So, what are the connections made here between boss/curator and employee/exhibitor? Each invitee is given a space of wall to present their firm’s work alongside a short information panel which, handily, highlights with images a couple of projects they worked on with Murphy before heading off on their own. The curation is not didactic, and any cohesive narrative is really left up to the visitor to infer, though there are some clues here: Kris Grant worked for Murphy on the Dunfermline Carnegie Library & Galleries in Fife which has an aesthetic conversation with the two garden pavilions he designed and presents here; and Weiz Train and Bus Stations in Austria by Jordi Sanahuja i Vidal have a dramaturgy reflected on in the architects’ reminiscing of his one year working at RMA.

“I think all of them subscribe to the point of view that you can do potentially radical things with historic buildings,” Murphy observes of his selection, “and secondly, I think they all have got a very strong social idea about what architecture is, about how it works, about people – and you wouldn't get that if you're working at Zaha Hadid’s office, for example, where it's all about sculptural form.”

In other contributors’ displays, direct lineage is less visible, though their texts discuss approaches carried on from Richard Murphy Architects into their own work, of rooflights, materials, detailing, and floorplans. “There are probably too many words in the exhibition,” Murphy says. There are a lot, though the issue is less the amount of words (which are, rarely for an architecture exhibition, written without jargon or overly-academic flourishes) but more that they have to do the curatorial work where curation and exhibition do not.

fig.vi

Murphy spent four years working under Metzstein at the University of Edinburgh. While he then had no time for designing, it did give him the space to explore and research Carlo Scarpa, publishing his first of three books on the architect in 1990. “Then I looked at all my fellow teachers and I thought ‘shit, if I don't get out now I will turn into one of them!’ I wasn't doing any building and I don't think students respect you if you don't build, or if you haven't built – it’s a bit like having a piano teacher who never plays the piano.”

Since leaving academia, Murphy has designed many buildings, including several for the cultural sector – including Perth Theatre, the British Golf Museum, Dundee Contemporary Arts, and ongoing plans for the Scottish National Centre for Music. This doesn’t mean, however, that the architect reaches far beyond the silo of architecture, its canon, and modes of representation and discourse in his work.

“There are a lot of people trying to twist my arm to become president of the RSA,” he says, but is quick to add that “the trouble is, I don't know enough about art! People would find me out – ‘Don't worry about that, you're an architect, you're not expected to know about art,’ they say, but if you ask me to name ten living Scottish artists I’d struggle.” Murphy’s extra-curricular culture is mainly in music, including singing in the Scottish Chamber Orchestra choir.

figs.vii-ix

There is generosity in the intent of Generation. Murphy recognises that his practice’s work expanded on and riffed off ideas from the likes of Scarpa, Cullinan, and MacCormac. “There's no question that the stuff I do is a consequence of their work,” he says, and wanting to “skip a generation” to then follow that family tree to those who worked under him is potentially interesting – even if he is still the focus of the exhibition through acting as the generational conduit and glowingly discussed in the participants’ texts.

The exhibition, however, needs a curator who is not situated at the centre of that story, and it needs to explore in and around the subject in a more curious, creative, and engaging way than solely using panels of text and photographs. Murphy’s lack of interest in art, exhibitions, and wider modes of cultural representation beyond traditional architectural pin-ups is very present and there is perhaps a missed opportunity by not introducing external eye looking in, critically, upon such a premise of the family tree as a pathway of idea and approach.

fig.x

There are design ideas that flow from Scarpa and Cullinan, through Murphy and then to another generation, and there are also pedagogical and theoretical ideas that also descend. There is also plenty of scope for exhibitions about architecture that de-centre the craft away from narratives of the singular genius towards ideas of shared making, re-making, learning, and lending. However, by essentially acting as a promotional platform for a few young architect practices, leaning in on the tired (and inaccessible to most visitors) curatorial approach of plans, photos, and text on panels, and by being solely made by the very people the exhibition considers, Generation misses that opportunity.

Just as one may criticise architectural educators who do not practice architecture failing to understand the medium they teach, so too there may be a lesson here about architects making exhibitions who similarly do not understand the medium or art of curation. There is an interesting exhibition to be made about how ideas and aesthetic sinuously travel through designs, research, education, and studio, and such a project could easily root itself in a city such as Edinburgh, using architectural history, present, and future. Such an exhibition could easily use RMA’s built and speculative projects for the city as well as Richard Murphy’s research on Scarpa to explore such a generational sharing of knowledge.

Richard Murphy RSA founded the practice of Richard Murphy Architects in 1991 and has since won 27 RIBA or RIAI awards, more than any other practice in Scotland. Awards range across many building types, including education, the arts, healthcare and housing, and demonstrate both the high design standards of the practice generally and also its versatility.

Richard Murphy Architects defines its goals as to make architecture equally of its place and of its time. Our projects illustrate that approach, looking equally at careful contextual responses to designing within and adjacent to existing buildings and also constructing new buildings within the contexts of established landscape and urban patterns.

Murphy is design leader in the practice for all projects and his work has ranged from domestic through to public and private housing; theatres and arts centres, buildings for education and health and two British Embassies. In 2006 Murphy was voted ‘Scottish Architect of the Year’ by the readers of Prospect Magazine. In the Queen’s New Year’s Honours 2007, he was awarded an OBE.

www.richardmurphyarchitects.com

The Royal Scottish Academy, founded in 1826, supports art and architecture in Scotland. It is

an independent, non-governmental institution, governed by Members to operate on a

charitable basis. The RSA runs a year-round programme of exhibitions, artist opportunities

and events from its base at the Mound, Edinburgh, and cares for a nationally recognised

collection. It supports artists and architects through awards, residencies, scholarships and

bursaries.

In 2026 the RSA will celebrate its 200th anniversary. It is marking this occasion nationwide by bringing hundreds of artists, partners, galleries, and institutions together for an

extraordinary year of exhibitions, events, and performances.

www.royalscottishacademy.org

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett, is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios & is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics.

www.willjennings.info

In 2026 the RSA will celebrate its 200th anniversary. It is marking this occasion nationwide by bringing hundreds of artists, partners, galleries, and institutions together for an extraordinary year of exhibitions, events, and performances.

www.royalscottishacademy.org