Lost in a just-in-time supply chain: a sculptural study of site

In a playful, radical re-appropriation of a former clothes shop in south London, a group of local emerging artists explore site, material, and late-capitalism. Curated by Josh C. Wright, the show is an exciting visual clash of large-scale sculpture, misleading materials, and an exploration of the built world, as experienced by Will Jennings.

The guts of the building seem to be splaying out through a

ceiling tile. Years of detritus of the shop’s fittings and fabric exuded from

its recesses as if the building had simply had enough, a reflex in its late-capitalist

guts regurgitating remnants of underlay, carpet tiles, plastics, and

plywood. Solidly connecting the ceiling and floor, it felt structural. If the

waste column was to be removed, perhaps the whole commercial edifice would come

tumbling down.

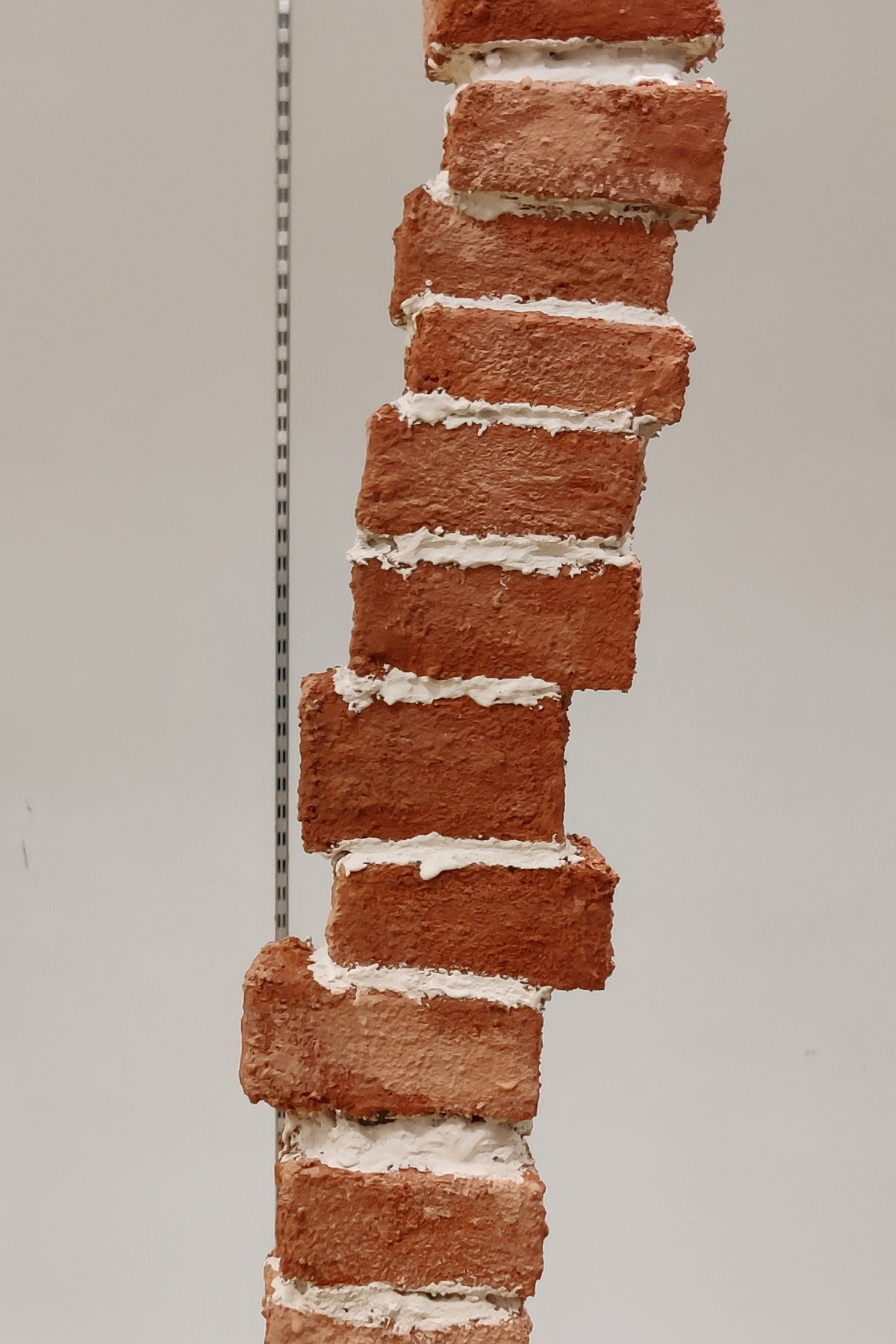

Deeper into the former Peacocks clothes store, another column was seemingly formed of drunkenly laid bricks, a single haphazard tower just about clinging onto stability. Don’t get too close, if the mortar crumbles any more bricks would collapse into a pile, probably followed by the roof.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The two sets of supporting structures are sculptures, the first Underlay (rude, enormous monoliths) (2022) by Catriona Robertson, and the clumsy brick Cloud to Ground (2022) by Josh C. Wright. Wright is not only an artist, but also curator of this group exhibition pulling together large-scale sculptural works from emerging artists in Southeast London, each utilising found materials from the landscapes of commerce and construction to critique and play with ideas of short-termism, disposability, and precarity of the day.

The exhibition, Lost in a Just-in-Time Supply Chain, features ten artists, undaunted by the scale of the former fast-fashion shop, provided to Wright by Hypha Studios, a charity placing artists into empty high-street commercial spaces for free to test new ideas and support culture outside of the gallery system. In the shop window, where once mannequins might have presented the season’s looks to those waiting at the bus stop outside, an archaeological lump of rock now sits, a fragment of another age. Rob Branigan’s Checkout (2019) sat as if hewn from a concrete floor, the recessed imprint of a shopping basket suggests some cataclysmic event, Lewisham’s Pompei moment.

![]()

Deep at the back of the cavernous storespace was Well Hung (2016), Alexandra Searle’s polyester resin and fibreglass work dangling from the ceiling substructure by a single strap, as if the former Peacock’s balls awaiting castration. Here, as with Robertson’s sculptural seepage and also in another Searle piece, Swell (2022), in which a floaty, bulbous yellow lump collapses over a cable, there is a sense of the organic taking over the space. Some of these sculptures appear is if they have grown here, rather than were constructed in place by an artist.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The shop is in an intermediate phase. Around one in seven high street stores lay empty, and conversations flood architecture, political, and urban sectors about what the future-high street may look like. After the exhibition this unit will become a Pure Gym, but most empty shops have a less certain future in an economy of online-shopping and post-Brexit economic nervousness. Gabriela Pelczarska plays on the strength of the high street’s urban infrastructure, as well as the cultural and social burden they support, with her sculpture Big Hug (2022). One of the buildings real pillars seemingly supporting the weight of a rock lashed to it with a single strap.

![]()

Next to it, another piece by Wright, Stack (Notice for Proposed Development) (2022), fills the height with three apparent crumbling concrete cubes, as architectural abandonment or parts awaiting deployment to an unknown built future. Attached, his comedically clumsy brickwork as seen in the spindly pillar returns in two pieces which sit like badly formed brick-skin panels. In developer-led building, the value of brick is not in its architectural function but it’s aesthetic appearance, and Wright’s brick pieces remind of cladding panels with a front of slim trim of brick, to give a building the value of brick solidity without using them structurally at all.

The notion of value returns in Conor Ackhurst’s Double Coupler (2021), a marble rendition of a scaffold knuckle, presented here on a plinth formed of scaffolding. More marble nearby, a rectangular slab trapping a semi-deflated basketball as it leans against the wall. Another work by Pelczarska, No Ball Games (2022), perhaps calling into question the value systems at play in our built landscapes, which can prioritise a polished material finish at the expense of people or activity designed out of a place.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

These are large works, and created by young artists who would normally not have access to space of enough size to contain their scale or ambition. At a time when culture is squeezed out of curricula and the everyday experience, and when the cultural sector is dominated by a gallery system and controlled spaces of cultural power, it may take emptied high-street spaces like this to provide the carcasses for a new culture to emerge. That culture, as can be seen in this show, can be playful, experimental, not beholden to a bigger system, and through that offer a critique of the very space, city, and society in which it sits.

![]()

Deeper into the former Peacocks clothes store, another column was seemingly formed of drunkenly laid bricks, a single haphazard tower just about clinging onto stability. Don’t get too close, if the mortar crumbles any more bricks would collapse into a pile, probably followed by the roof.

figs.i-iii

The two sets of supporting structures are sculptures, the first Underlay (rude, enormous monoliths) (2022) by Catriona Robertson, and the clumsy brick Cloud to Ground (2022) by Josh C. Wright. Wright is not only an artist, but also curator of this group exhibition pulling together large-scale sculptural works from emerging artists in Southeast London, each utilising found materials from the landscapes of commerce and construction to critique and play with ideas of short-termism, disposability, and precarity of the day.

The exhibition, Lost in a Just-in-Time Supply Chain, features ten artists, undaunted by the scale of the former fast-fashion shop, provided to Wright by Hypha Studios, a charity placing artists into empty high-street commercial spaces for free to test new ideas and support culture outside of the gallery system. In the shop window, where once mannequins might have presented the season’s looks to those waiting at the bus stop outside, an archaeological lump of rock now sits, a fragment of another age. Rob Branigan’s Checkout (2019) sat as if hewn from a concrete floor, the recessed imprint of a shopping basket suggests some cataclysmic event, Lewisham’s Pompei moment.

fig.iv

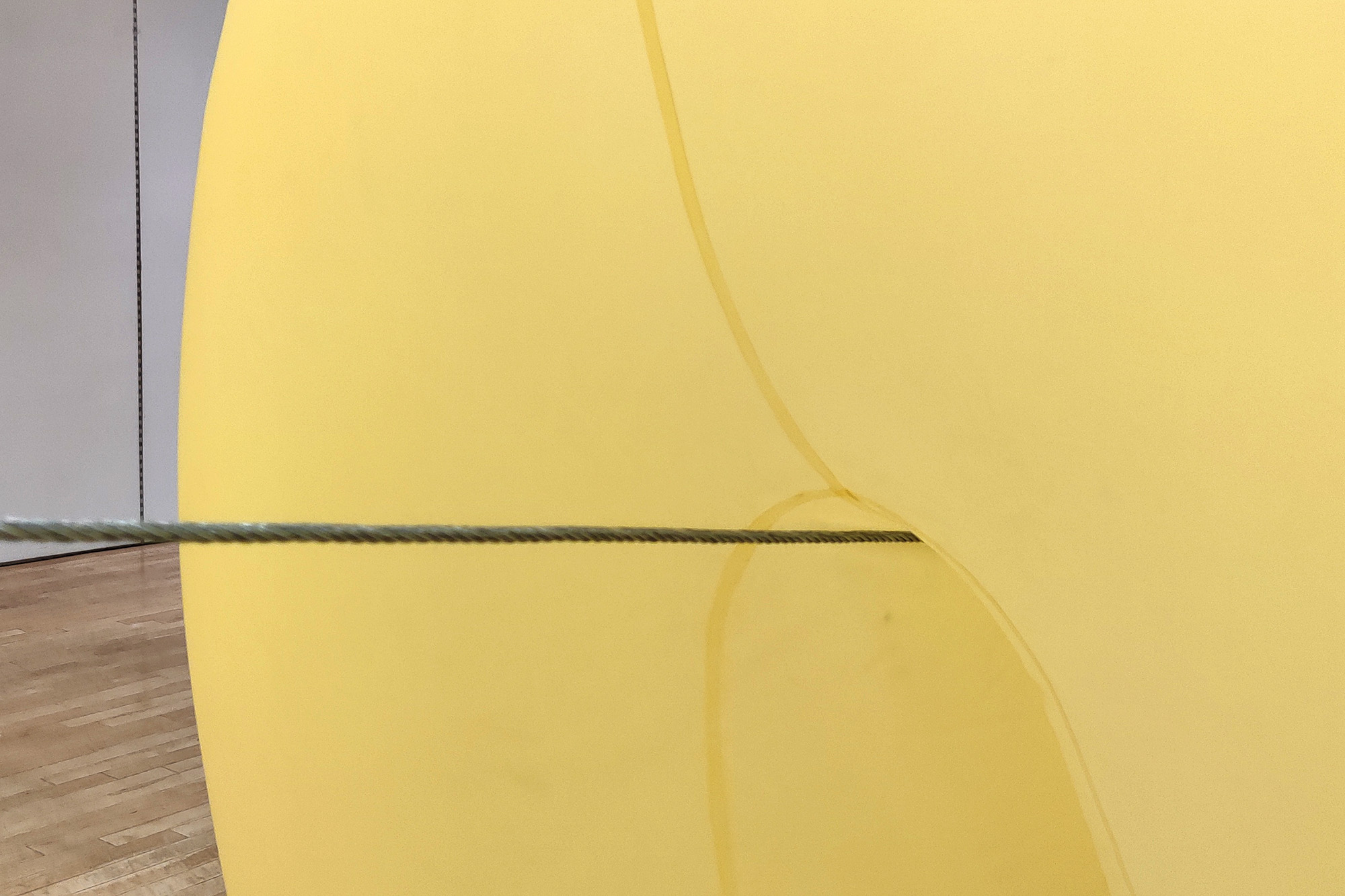

Deep at the back of the cavernous storespace was Well Hung (2016), Alexandra Searle’s polyester resin and fibreglass work dangling from the ceiling substructure by a single strap, as if the former Peacock’s balls awaiting castration. Here, as with Robertson’s sculptural seepage and also in another Searle piece, Swell (2022), in which a floaty, bulbous yellow lump collapses over a cable, there is a sense of the organic taking over the space. Some of these sculptures appear is if they have grown here, rather than were constructed in place by an artist.

figs.v-vii

The shop is in an intermediate phase. Around one in seven high street stores lay empty, and conversations flood architecture, political, and urban sectors about what the future-high street may look like. After the exhibition this unit will become a Pure Gym, but most empty shops have a less certain future in an economy of online-shopping and post-Brexit economic nervousness. Gabriela Pelczarska plays on the strength of the high street’s urban infrastructure, as well as the cultural and social burden they support, with her sculpture Big Hug (2022). One of the buildings real pillars seemingly supporting the weight of a rock lashed to it with a single strap.

fig.viii

Next to it, another piece by Wright, Stack (Notice for Proposed Development) (2022), fills the height with three apparent crumbling concrete cubes, as architectural abandonment or parts awaiting deployment to an unknown built future. Attached, his comedically clumsy brickwork as seen in the spindly pillar returns in two pieces which sit like badly formed brick-skin panels. In developer-led building, the value of brick is not in its architectural function but it’s aesthetic appearance, and Wright’s brick pieces remind of cladding panels with a front of slim trim of brick, to give a building the value of brick solidity without using them structurally at all.

The notion of value returns in Conor Ackhurst’s Double Coupler (2021), a marble rendition of a scaffold knuckle, presented here on a plinth formed of scaffolding. More marble nearby, a rectangular slab trapping a semi-deflated basketball as it leans against the wall. Another work by Pelczarska, No Ball Games (2022), perhaps calling into question the value systems at play in our built landscapes, which can prioritise a polished material finish at the expense of people or activity designed out of a place.

figs.ix-xii

These are large works, and created by young artists who would normally not have access to space of enough size to contain their scale or ambition. At a time when culture is squeezed out of curricula and the everyday experience, and when the cultural sector is dominated by a gallery system and controlled spaces of cultural power, it may take emptied high-street spaces like this to provide the carcasses for a new culture to emerge. That culture, as can be seen in this show, can be playful, experimental, not beholden to a bigger system, and through that offer a critique of the very space, city, and society in which it sits.

fig.xiii

Josh C. Wright is an early career artist living in Deptford.

Having studied sculpture at Camberwell College of Arts and residing in South

London ever since he is actively involved in the South London Arts community.

Josh’s practice is predominantly sculptural, he salvages construction material

and re-used domestic objects making precarious and uneasy forms. Since the start of 2020, he was shortlisted for the

prestigious Ingram Prize, published his first artist book and most recently

curated and featured in the group show The House Protects The Dreamer at D

Contemporary in Mayfair.

www.joshcwright.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info

visit

Lost in a Just-In-Time Supply Chain is an

exhibition of artists all living and/or working in the Borough of Lewisham and

neighbouring Greenwich and Southwark. Responding to the idea of the ‘site’,

each artist in their own way draws inspiration from the city’s physical and

conceptual landscape, utilising DIY and construction supplies, waste and

salvaged material. True to its name, our just-in-time schedule will

operate for just FOUR DAYS ONLY before our artists, artworks and materials are

dispersed, this project with Hypha Studios ends and a vacant Peacocks shop

becomes Pure Gym.

28 April - 01 May, 2022

96-102 Rushey Green

London, SE6 4HW

www.hyphastudios.com/event/lost-in-a-just-in-time-supply-chain-exhibition

Artists:

Conor Ackhurst ︎

Rob Branigan ︎

Patrick Cole

︎

Jack Evans

︎

Gabriela Pelczarska

︎

Anna Reading

︎

Catriona Robertson

︎

Alexandra Searle

︎

Alex Williamson

︎

Josh C. Wright

︎

images

fig.i Catriona Robertson, Underlay (rude, enormous monoliths), 2022, Concrete, Paper-concrete, Rubble, Discarded Carpet Tiles, Foam Underlay Offcuts, Polyurethane, Resin, Vacuum Form, Corrugated Plastic, steel, Plywood, Timber. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph

© Rob Harris.

fig.ii Josh C. Wright, Cloud to Ground, 2022. Jesmonite, household insulation, expanding foam and wood. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph

© Rob Harris.

fig.iii

Josh C. Wright, Detail of Cloud to Ground, 2022. Jesmonite, household insulation, expanding foam and wood. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph

© Will Jennings

fig.iv Rob Branigan. Checkout. 2019. Concrete.

Courtesy of the artist. Photograph

© Will Jennings.

fig.v Alexandra Searle, Well Hung, 2015. Polyester resin, Fibreglass, Ratchet Strap. Courtesy of the

artist.

Photograph

© Rob Harris.

fig.vi Alexandra Searle, Detail of Swell, 2022. TPU, Tension Wire, Air. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph

© Will Jennings.

fig.vii Alexandra Searle, Swell, 2022. TPU, Tension Wire, Air. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph

© Rob Harris.

fig.viii Installation View of Lost in a Just-In-Time Supply Chain, including:

Patrick Cole, Wreck, 2022. Durational Performance. Cardboard, Wood, Emulsion. Courtesy of

the artist.

Gabriela Pelczarska. Big Hug. 2022. Concrete, Foam, Ratchet strap, Pillar.

Courtesy of

the artist.

Josh C. Wright, Stack (Notice for Proposed Development), 2022.

Josh C. Wright,

Caving In, 2021

Josh C. Wright,

Lost Chairboy, 2022.

All courtesy of the artists.

Photograph

© Rob Harris.

fig.ix Conor Ackhurst, Detail of Double Coupler, 2021. Marble, Scaffolding. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph

© Will Jennings.

fig.x

Conor Ackhurst, Detail of Double Coupler, 2021. Marble, Scaffolding. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph

© Rob Harris.

fig.xi Gabriela Pelczarska, Detail of No Ball Games, 2022, Marble, Basketball. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph

© Rob Harris.

fig.xii

Gabriela Pelczarska, No Ball Games, 2022, Marble, Basketball. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph

© Will Jennings.

fig.xiii Installation View of Lost in a Just-In-Time Supply Chain, Hypha Studios Catford, London.

Photograph

© Rob Harris.

publication date

29 April 2022

tags

Brick, Catford, Conor Ackhurst, Rob Branigan, Capitalism, Patrick Cole, Commerce, Jack Evans, High street, Hypha Studios, Lewisham, London, Marble, Gabriela Pelczarska, Anna Reading, Catriona Robertson, Scaffold, Sculpture, Alexandra Searle, Shop, Shopping, Alex Williamson, Josh C Wright

28 April - 01 May, 2022

96-102 Rushey Green

London, SE6 4HW

www.hyphastudios.com/event/lost-in-a-just-in-time-supply-chain-exhibition

Artists:

Conor Ackhurst ︎

Rob Branigan ︎

Patrick Cole ︎

Jack Evans ︎

Gabriela Pelczarska ︎

Anna Reading ︎

Catriona Robertson ︎

Alexandra Searle ︎

Alex Williamson ︎

Josh C. Wright ︎