ASMR, sense & the city: an interview with James Taylor-Foster

James Taylor-Foster is curator of contemporary architecture and design at ArkDes, the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design. His exhibition WEIRD SENSATION FEELS GOOD: The World of ASMR is currently on display in London’s Design Museum. In this conversation with Will Jennings, he discusses the history & culture, of ASMR as well as how it intersects with architectural & social issues.

Will Jennings:

First of all, just explain what is ASMR? Because obviously, everyone has their own idea of what it is.

James Taylor-Foster:

The tricky thing is, of course, that ASMR shouldn't really be defined, because it is in this constant state of definition and redefinition in its own right, like any kind of movement. It's very young, as an Internet movement, you can basically trace it back to 2009, but even that history is a little bit ambiguous. But in the context of an exhibition you have to define things, and I find that's one of the most problematic parts around my kind of curatorial work, which often tries to touch upon rather ephemeral things, is that question of always having to define it, because you have to also provide that moment of access to somebody who has never heard of it.

ASMR is a term that describes a physical sensation, which can range from something like euphoria – and this is where the tingling feeling comes from – or a sensation of deep calm and relaxation. The tingling in the body is when we're in one of these situations where we have no idea of what is happening, somewhere between the psychological and the physiological, and that is my way into describing ASMR as a form of design that mediates between mind and body. The reason that becomes somehow interesting is because maybe ASMR is tapping into this whole understanding that we are not body and mind – they're not two separate things, but completely synthesised.

With ASMR, often people will go back to a childhood experience. For me, that's also true. I very, very clearly remember what must have been year three at school, I was verysmall and remember being in a classroom with everybody cutting shapes from cardboard. And I remember being so incapacitated by the combination of the sound of the scissors through the cardboard, the sight of the scissors, the movement, but also the concentration and atmosphere in the room. And what's interesting about my example is it brings together three core aspects of ASMR – it’s not just audio and visual, but also something about movement. Something is happening to the eyes, something is happening sonically – they're usually aligned, things I would describe as tangible triggers. Then there are intangible triggers, and intangible triggers are really more emotionally based.

figs.i,ii

In the exhibition, we have seven works by Bob Ross, a fairly iconic figure, but also an interesting bridge point within ASMR. He's cross-generationally understood. Some people recall running home from school in the 80s or 90s and watching an episode of The Joy of Painting and they didn't quite know why they enjoyed it, because they certainly weren't learning to paint. Then people under the age of 25 might have seen Bob Ross as a meme, this guy with an afro-like-perm delicately painting canvases. So you have this unique combination of tangible and intangible triggers. The brushing is tangible, you have the completion of a canvas that is oddly satisfying and tangible. Then you have intangible triggers: his soft spoken words, his positive affirmations, this general atmosphere of safety, calmness, and positivity. Bob Ross embodies everything that ASMR has come to represent or endorse. That is a clue to understanding that ASMR is not new – the term might be new, but ASMR is completely primordial. I mean, what is sound if not a form of touch?

The exhibition looks a lot like a series of microphones. I think what's interesting about microphones, but also in-ear earphones – the most intrusive forms of wearable technology that we have – is that ASMR can replicate a form of touch through headphones. Maybe you turn the volume up and hear that whisper it can feel very real, it can induce a sort of trance like state. ASMR is fairly undefinable and highly individual. Yet, when you look at it in its totality in 2022, there is something cohesive happening that can be that can be understood, even if that cohesion is constantly morphing into something else.

figs.iii,iv

It was interesting to launch the exhibition at ArkDes in Sweden over COVID, when we couldn't touch, when we couldn't be in proximity to one another, and you were exploring the imitation of touch just when we were being deprived of it, in an exhibition talking about how it could be simulated or reimagined. Can ASMR ever involve touch, or does it have to have a physical distance?

By some quirk of fate, the first exhibition opened in April 2020, a week before it closed in a moment of incredible fear, and the Design Museum opening is just two years later at the end – if we are being optimistic – of the worst of the pandemic. So these two exhibitions book-end this extremely bizarre period of time, in which we're still waiting for the online data, but I'm convinced that ASMR experience has skyrocketed during this period for two reasons: one, people have had the space to discover it; and secondly, people have needed to have that form of self-medication in an incredibly anxiety inducing moment.

figs.v,vi

I guess our relationship to technology, on a very subtle level, has completely changed. It's embedded within family life, or shopping, in a way that not all. So it's probably also going to sit down to that psychological and caring level.

Yeah, precisely. I don't think ASMR replaces physical touch. It's trying to imitate it in many situations where people might not have access to physical touch, and I think that that obviously becomes even more poignant during the pandemic as well. We have lived mediated lives, where families, people from different generations, have had to get used to Zoom or FaceTime, and I think we all realise that technology might not be the answer to the emotional needs that we all have as human beings. In the exhibition I tried to say that we are in a moment of a new digital intimacy, a new emotional economy of care, which we're negotiating right now.

We understood that half the objects in the exhibition can just be watched on YouTube. So there is something else that the exhibition space is doing, which is trying to understand if we can lift things out from the screen, put them into a public space, create a space that allows for vulnerability, and then see if you can feel in that space.

figs.vii,viii

The implication of vulnerability is really interesting and has much wider implications for all kinds of design, not just exhibition and the safe-space of a ticketed, curated, secured space. But in Britain we have Secured by Design, where the police have a design team involved with design projects on an urban scale to make it safer – which could mean anti-homeless street furniture, or it could be how roads are shaped. In Ashford, Kent, the local Secure by Design police team removed shrubs and benches from a park, saying they incite “antisocial behaviour”. So do we allow for spaces of vulnerability? London has the whole King's Cross, Nine Elms, and Docklands developments all privately owned, secured, organised, surveilled at different levels, and there's no room for vulnerability in that. I wonder if then we can learn from your idea of vulnerability a broader architectural and social sense?

Absolutely. Museums are highly behaviourally codified environments, which demand you to have certain assumptions. I think that that's something that we take for granted, those who were taken to museums as kids have that sort of inbuilt experience, which is connected to class, to what kind of education you had, to where you are in the world, and this kind of stuff. But what we are also trying to do in a way is very subtly challenge those assumptions and codified behaviours of the museum.

I'm only interested in experience driven exhibition projects, and this is probably the ultimate so far I've managed to facilitate. There is no text in the exhibition – there’s an introduction text and some definitions, then that's it other than a booklet you can carry around. It’s a subtle effort to remove as many thresholds as possible, to simply just be in the space – I’m convinced that we don't go to exhibitions to look at objects, we go to exhibitions to look at other people first as inherently social experiences, and Weird Sensation Feels Good tries to acknowledge that social experience.

figs.ix,x

So ĒTER, the exhibition architects based in Riga, created an oval shaped arena lined with kilometres of sausage-pillow in which you sit. You can be there for ten minutes or two hours, and in that room you will be looking at works but also at the person opposite you, understanding what's happening on their face, as they look at you there’ll be a combination of eye contact with that combination of proximity between strangers. That is part of the recipe to create an environment which allows for vulnerability.

Although I would describe Arkdes as a public space, because we are a government institution and every single square metre is owned by the Swedish taxpayer, the Design Museum is something very different. The exhibition was free of charge in Sweden, but is 10 quid in London, these are two very different contexts. Also, the Design Museum gallery we're in is the basement, and you're in a room with no windows. It's quite womb-like, it holds you, and I think that the passing of time becomes a bit ambiguous. The dwell time of this exhibition is enormous – most exhibitions have a dwell time of 30 minutes, in Arkdes we had a dwell time of two and a half hours. So we're already heading to somewhere people might feel safe. We do not understand that duration time is of value to public spaces, or urban environments. There are few moments in London where you stop, and maybe that highlights the importance of a certain kind of public space, like a square – the arena in the exhibition is sort of a public square that's soft.

That leads me to the second thing, softness. The hardness of public space is nothing new, in the West public spaces were always defined by this strange idea of permanence, or impermeability. Granite can be soft, but not when it's hewn and hacked into these blocks - it's done for efficiency, for cleaning, but also to alienate unwelcome people such as the homeless. It doesn't have to be about homeless spikes, it can also be something that slopes at a certain angle so that you can't actually lay on it. It can be violent in the most subtle ways. But softness is grass, hedgerows, and it is a visual thing as much as a thing to touch. If you eat with your eyes, you also detect a feeling of something when you see it, before you actually engage with it. So, I think that you can extrapolate a lot of the design intentions behind Weird Sensation Feels Good onto public space. We live in an extremely harsh environment in which slowness is not allowed.

figs.xi,xii

What about this idea of the weird. The unusual and unexpected, which is in ASMR – it’s weird to have those feelings – but also many of the things being done are weird – to caress a microphone, squeeze toothpaste out, or whatever generates the sounds, they can be weird actions when taken out of context. Do we allow for the weird anymore in design and cities? And does this feed into those urban spaces you talk about, that feeling of transition rather than experience?

The exhibition title comes from a health message board called health.com, the first moment in which ASMR was described on the internet. The headline of that of that message thread was all capital letters: WEIRD SENSATION FEELS GOOD. You can't really describe it better – it’s not totally accurate, because I think that the word weird is a bit charged. Feels good? It doesn't always feel good to people, people can have like a misophonic response, misophonia being when you have a very negative response to mouth sounds like licking or chewing. But weirdness is an individual response.

That individual question becomes quite interesting when we think of cities because I get really frustrated, for example, when you see councils or government mandates, saying that “a city designed for children is a city designed for everybody”. That's wrong, because cities should be conflictual, cities should be messy. Gay cruising should – even though it might be weird for some – have space in the city as much as children's playgrounds, which might be weird for other people.

figs.xiii,xiv

I think what I really like about ASMR is that within this loose framework of trying to help you fall asleep, or trying to reduce anxiety, there is this absolute plethora of diversity, an inherent diversity with how you achieve a goal. And part of part of the joy I think of engaging with ASMR as someone who is not an ASMR test is that discovery, and when people say I don't feel anything that is my I don't, it's not for me, I'm like, okay, but you may not have found that one thing that might trigger a memory from your childhood or might do something that actually might make you feel something that you might not have felt before. So that journey is about being engaged on. What I think our issue is with cities is that we are we're just removing diversity. I think that they can be too ordered.

If you want to have a protest, you have to apply two weeks in advance for approval – it’s not just about physicality, it's about the layers of permission and bureaucracy, and the gamification of the city which also creates this kind of control. What frightens me is that is that we are losing that diversity in which you can do things that are weird to some people, but might not be weird to you, this kind of smoothing of the public realm, the smoothing of the housing market, the smoothing of these things requires elimination. It’s more subtractive than additive and that is so frightening, because it's all done in the name of safety.

I think that we need to also understand much more than safety, fear is about belonging, safety is about feeling secure – as a body, in social situations, in gatherings – and I think that that may be that harks back to the exhibition which in different way is trying to say: “you're gonna walk into this room and the one thing we ask you is that you have an open mind and an open body in the way you receive feelings.”

figs.xv,xvi

2009 – from when you can trace ASMR to – to today is only 13 years. Equally, the internet from when it became public in 1996 or so to now is a very different beast – it’s become commodified, gated, and capitalised as any sort of spatial territory has been through history. How will technology change and will ASMR go the same way as the internet technology has and just become commodified by Tik Tok as a feelgood button to press every so often?

ASMR is being commodified as a format. In the exhibition there are three examples of advertisements that use ASMR, for example by IKEA and Virgin Atlantic. But, ASMR in another 13 years I'm convinced will exist in some format. But there are bigger questions attached to that: in 13 years will we actually understand what is happening to the brain, to the central nervous system, to the body? It’s very likely that we will. There's now an organisation called ASMR Net, a global organisation of researchers actively looking into it. And in the exhibition, actually, Dr. Giulia Poerio from the University of Essex has a clinical survey in the exhibition which visitors will be invited to fill in, and that data will feed into the to their ongoing research. But she’s also doing brain scans, all sorts of research around gender, sexuality, and age. Dr. Craig Richard, a Professor of Biopharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Shenandoah, runs the ASMR University and is convinced that ASMR should be offered to deal with anxiety disorders, as a mental health tool, so his research is focused on ASMR in clinical conditions. There are these people pushing at these boundaries trying to see if ASMR can not just be a cultural movement but also have a serious impact within healthcare. That I think is one potential sort of longevity of the cultural creative field, movement, and community.

The community is crucial. This is at its base at the internet community, and a very nice one. You know, two years ago I would scroll down YouTube ASMR videos and there was zero trolling on the comments, it was literally – and still is – this world of softness, a world of gentleness, of niceness, slowness, and at a moment in which technology is just accelerating. What I find so interesting about ASMR is that it took YouTube, smartphones, bandwidth, it took all these things designed for speed and carved out a niche within them of slowness and softness. I think it proves that there is some resistance to the condition that we're in right now, to this endless optimism that technology somehow embodies.

The debate over the last decade has been about attention and the potential risks of this much screen time, of this much access to information. No one planned ASMR, there was no strategy behind it, it just emerged, and I think the idea that something can emerge that’s transcultural, translingual, and that can take the best of the internet and do something else with it is great. There will be physical technologies that really deal with ASMR I think, and that's going to be interesting to see, and it dovetails with the question of how haptic the internet could be. We're starting to see with VR glasses or the Oculus vibrators you can put on your body so you can really feel when someone hits your body space.

figs.xvii,xviii

And as with the printing press and the internet, perhaps porn is going to be the thing that pushes a lot of these technologies.

Porn is always there, isn't it? Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response is essentially a meaningless combination of words, but there's a reason for those words that Jennifer Allen coined to galvanise the movement back in 2009, particularly away from words such as braingasm – she was particularly against the early linguistic sexualization of the term.

I would not argue that it's sexual – at its core it's sensual – but it's about intention. It's not the intention of most ASMR artists to sexually stimulate the viewer. But then if you go on PornHub and type in ASMR, you'll find a tonne of people who also call themselves ASMR artists whose intention it is to actually stimulate you. So I think that there is this strange blob that is ASMR, kind of moving around and growing. Now it's starting to grow in different directions. If I were to make a prediction, it's going to split into all sorts of different worlds based on different intentions, but at the same time it's going to not go anywhere because it is in itself inherent within us – ASMR goes back to you being a baby and softly whispered to in your ear, or gently stroked, it tries to re-engage those very, very human experiences.

This perhaps speaks to our current awareness of ecology in the Anthropocene, and re-engaging with nature, with existence.

fig.xix

James Taylor-Foster is a writer and cultural critic trained in architecture. He is the curator of contemporary architecture and design at ArkDes, the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design. In 2016 he co-curated the Nordic Pavilion at the 15th Biennale Architettura di Venezia and in 2018 participated in the central exhibition at the 16th. He has developed a number of curatorial projects in Stockholm including, most recently, the first museum exhibition to explore the culture and creative field of ASMR. He was formerly editor-at-large for ArchDaily.

www.james.tf

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info

visit

WEIRD SENSATION FEELS GOOD: The World of ASMR is exhibited at The Design Museum, London, until 16 October 2022.

www.designmuseum.org/exhibitions/weird-sensation-feels-good-the-world-of-asmr

images

fig.i Morning Mist by Bob Ross (1985)

©

Ed Reeve. for the Design Museum.

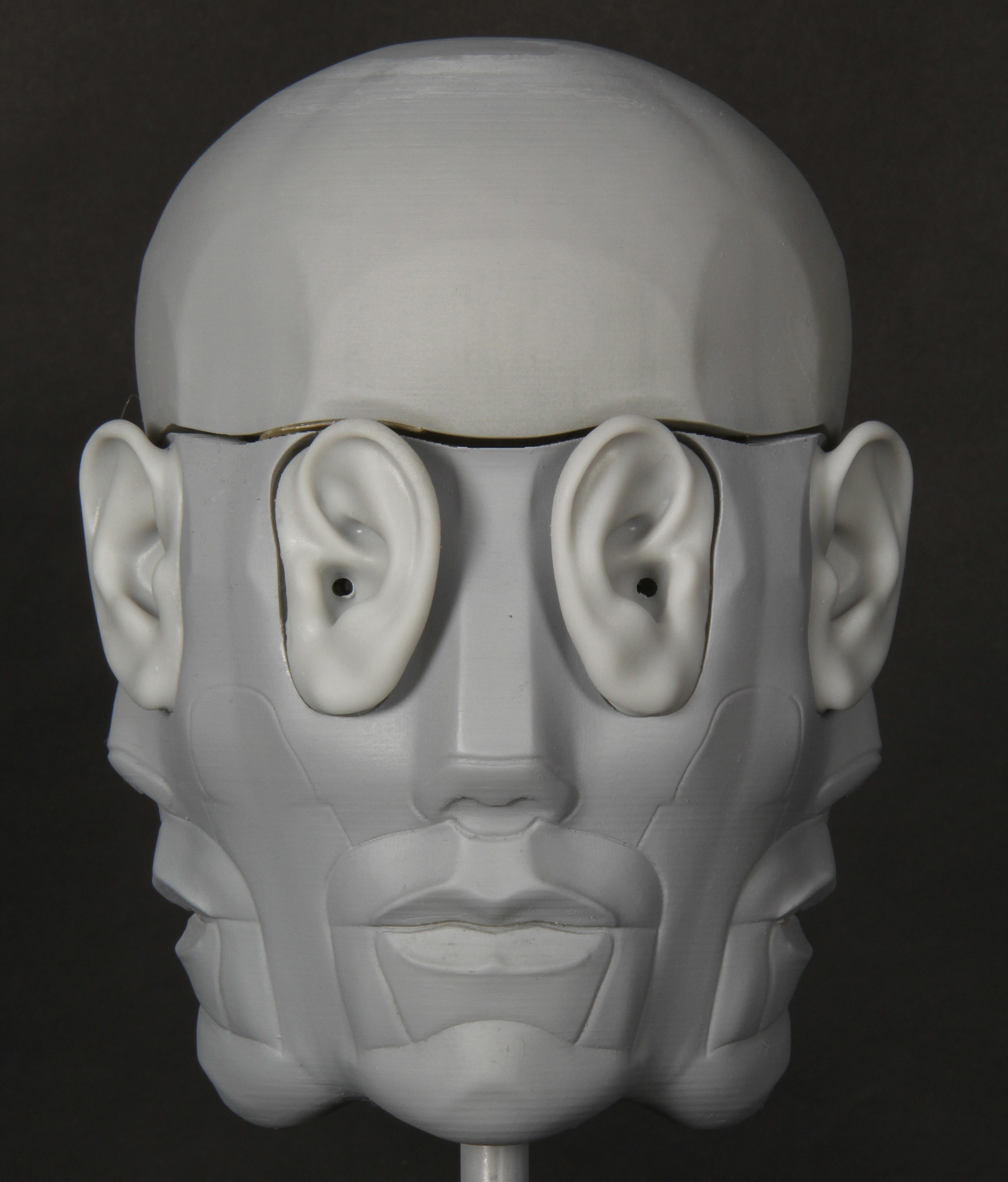

fig.ii Neumann KU 100 Dummy Head. With Binaural Stereo Microphone (1992).

©

Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.iii ASMR Arena. © Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.iv Tobias Bradford, that feeling_immeasureable thirst (2021). © Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

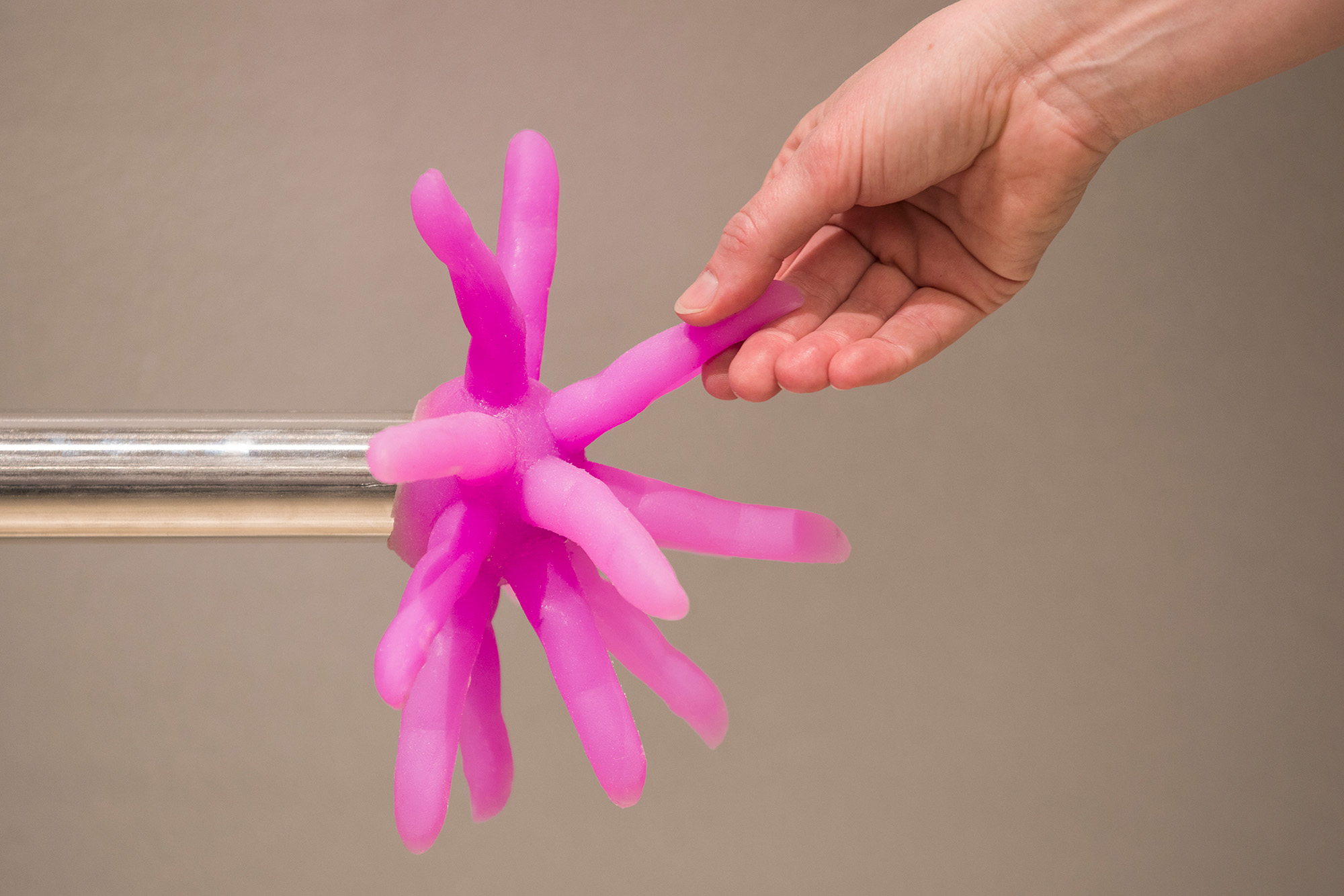

fig.v Meridians Meet, Interactive Commission Space by Julie Rose Bower. © Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.vi The Voice of Touch (2022).

©

Marc Teyssier.

fig.vii The Voice of Touch by Marc Tessier (2022). © Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.viii

©

Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

figs.ix,x ASMR Arena, Ed Reeve for the Design Museum.

© Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.xi Sound and Vision (2012).

©

Chris Milk.

fig.xii Chris Milk, Custom Built Binaural Microphone (2012).

© Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.xiii The Voice of Touch (2022).

©

Marc Teyssier.

fig.xiv Exhibition installation in ArkDes, Sweden.

fig.xv Neumann KU 100 Dummy head binaural stereo microphone for immersive 3-D sound, Courtesy of Georg Neumann GmbH.

fig.xvi Meridians Meet, Interactive Commission Space by Julie Rose Bower. © Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.xvii ASMR Arena. © Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.xviii Tobias Bradford, that feeling_immeasureable thirst (2021). © Ed Reeve, for the Design Museum.

fig.xix Portrait James Taylor-Foster.

publication date

02 August 2022

tags

ArkDes, ASMR, Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response, Covid, Design Museum, ĒTER, Will Jennings, Gay, Giulia Poerio, Ed Reeve, Craig Richard, Bob Ross, Marc Teyssier, Museums, Secured by design, Sense, Sex, Sound, James Taylor-Foster, Touch

www.designmuseum.org/exhibitions/weird-sensation-feels-good-the-world-of-asmr