Five women street artists you should know

A new book focuses in on 24 women street artists working in cities all over the world to find out what drives them, how politics comes into their visual practice, and how their work changes the urban settings it is designed for.

In a new book published by Prestel, author Alessandra Mattanza

has looked across the globe to select 24 female street artists, and used a wide

lens to consider how practitioners put (or paint, position, stitch, or paste)

their work into the urban fabric. In a richly illustrated book, through interviews

and project exploration each artist is presented to provide a look at how women’s

creative voices are heard, often in societies and built spaces designed by and

for men.

Below, we highlight just five of the included artists from Italy, Argentina, Iran, Poland, and South Africa, each using their creative language to bring colour, message, and play into the city:

![]()

MEDIANERES

Vanesa Galdeano and Anelí Chanquía, working under the name Medianeras, a Spanish word meaning party walls and thinking about architectures shared amongst a community. The Argentinian couple (in work and life) work with a traditional street-muralist approach, with large, flat end-of-block walls becoming vast canvases for magnified details of ordinary people with a style of mixing bold, colourful stripes with black and white. Galdeano studied architecture and fine arts, her interest in urban planning leading her towards community workshops and collective projects, which has directly fed into how their murals are now created.

![]()

CAMILLA FALSINI

Bold colour also infuses Italian illustrator and artist

Camilla Falsini’s work, pieces that the artist says are deliberately not

didactic, but designed to bring pleasure, evoke memories, or arouse an emotion.

Often working with clients from the UN to publishing houses, in 2021 Falsini

was invited to take part in Piazze Aperte, an urban redevelopment programme in

Milan. Working across the horizontality of Piazzale Loreto and Piazza Tito

Minniti, the artist radically changed the feel of the grey tarmacked areas.

![]()

OLEK

Play is a recurring theme in many of the selected women street artists, though often it can be a vehicle to introduce a political or activistic message. Using crochet as their art, artist Olek grew up in 1980s Poland, saying that “creativity came to me as a necessity, we had to make our own clothes … this forced me to make my own wonderland.” It’s a making which has continued, fuelled by her university studies into the symbolism of costume in the films of Peter Greenaway. Their practice now includes stitched sculptural forms, hanging banner like messaging, and performances in which participants wear colourful crocheted onesies and become genderless, faceless, raceless characters in the world she continues to invent.

![]()

FAITH47

Three years after South African apartheid came to an end, Faith47 started her street art practice as a self-taught artist. The social reality and physical legacy of that racist history remained present in Cape Town and its urban fabric, with her early works focusing in on poverty and economic inequality. Now a multidisciplinary artist working across sculpture, mural, tapestry, and painting, with work in collections including MUCA in Munich, her work seeks to project optimism and empathy within surrounding built landscapes which may represent a situation many may find it hard to see optimism. The work shown here, Medicinal flowers of Lebanon (2021), in Beirut, speaks to that: “we must cultivate and nurture within us optimism, faith, the hope of being able to go on trying and fighting for a better world, love, empathy, sustainability, cohesion, understanding, even as we confront the most horrifying prospects."

![]()

SHAMSIA HASSANI

While virtually every place on earth is organised patriarchally, with women still fighting for equality and recognition even in the most advanced states, for a female artist some nations are harder than others. Born to Afghan parents in Iran, Shamsia Hassani realised as a child that in her birth country there was no law allowing people to be considered citizens, and while retaining her Afghan nationality has meant she has grown up with freedoms her childhood friends have not, it did mean she was not permitted to study at art school. With desire and perseverance, however, Hassani did develop her practice, becoming a professor of drawing at Kabul University. Her urban drawing uses deliberately simple aesthetic to provide a face, voice, and representation to the broader female Afghan civic and artistic communities, bringing visibility and presence. The female character populating Hassani’s works has no mouth, but is regularly holding or playing a musical instrument, granting her “the power and confidence to speak and make her voice resound with strength.”

![]()

Below, we highlight just five of the included artists from Italy, Argentina, Iran, Poland, and South Africa, each using their creative language to bring colour, message, and play into the city:

MEDIANERES

Vanesa Galdeano and Anelí Chanquía, working under the name Medianeras, a Spanish word meaning party walls and thinking about architectures shared amongst a community. The Argentinian couple (in work and life) work with a traditional street-muralist approach, with large, flat end-of-block walls becoming vast canvases for magnified details of ordinary people with a style of mixing bold, colourful stripes with black and white. Galdeano studied architecture and fine arts, her interest in urban planning leading her towards community workshops and collective projects, which has directly fed into how their murals are now created.

CAMILLA FALSINI

OLEK

Play is a recurring theme in many of the selected women street artists, though often it can be a vehicle to introduce a political or activistic message. Using crochet as their art, artist Olek grew up in 1980s Poland, saying that “creativity came to me as a necessity, we had to make our own clothes … this forced me to make my own wonderland.” It’s a making which has continued, fuelled by her university studies into the symbolism of costume in the films of Peter Greenaway. Their practice now includes stitched sculptural forms, hanging banner like messaging, and performances in which participants wear colourful crocheted onesies and become genderless, faceless, raceless characters in the world she continues to invent.

FAITH47

Three years after South African apartheid came to an end, Faith47 started her street art practice as a self-taught artist. The social reality and physical legacy of that racist history remained present in Cape Town and its urban fabric, with her early works focusing in on poverty and economic inequality. Now a multidisciplinary artist working across sculpture, mural, tapestry, and painting, with work in collections including MUCA in Munich, her work seeks to project optimism and empathy within surrounding built landscapes which may represent a situation many may find it hard to see optimism. The work shown here, Medicinal flowers of Lebanon (2021), in Beirut, speaks to that: “we must cultivate and nurture within us optimism, faith, the hope of being able to go on trying and fighting for a better world, love, empathy, sustainability, cohesion, understanding, even as we confront the most horrifying prospects."

SHAMSIA HASSANI

While virtually every place on earth is organised patriarchally, with women still fighting for equality and recognition even in the most advanced states, for a female artist some nations are harder than others. Born to Afghan parents in Iran, Shamsia Hassani realised as a child that in her birth country there was no law allowing people to be considered citizens, and while retaining her Afghan nationality has meant she has grown up with freedoms her childhood friends have not, it did mean she was not permitted to study at art school. With desire and perseverance, however, Hassani did develop her practice, becoming a professor of drawing at Kabul University. Her urban drawing uses deliberately simple aesthetic to provide a face, voice, and representation to the broader female Afghan civic and artistic communities, bringing visibility and presence. The female character populating Hassani’s works has no mouth, but is regularly holding or playing a musical instrument, granting her “the power and confidence to speak and make her voice resound with strength.”

Alessandra Mattanza is a foreign correspondent, contributor,

and editor for several publishers in Italy and Germany. Her previous books are Street

Art: Famous Artists Talk About Their Vision and Banksy.

www.alessandramattanza.com

purchase

Women Street Artists by Alessandra Mattanza, with a forward

by Stephanie Utz, is published by Prestel and is available in book shops

widely.

More information available at:

www.prestelpublishing.penguinrandomhouse.de/book/Women-Street-Artists/Alessandra-Mattanza/Prestel-com/e605291.rhd

images

fig.i Medianeras, The Crystal Ship, Ostend, Belgium, 2021. Image courtesy the artist.

fig.ii Camilla Falsini, Tactical Urban Planning

Intervention, Milan, Italy, 2020: Photo: Jungle Agency.

fig.iii Olek, Charging Bull, Wall Street, New York City,

New York, USA, 2010. Image courtesy the artist.

fig.iv Faith47, Medicinal Flowers of Lebanon, Beirut, Lebanon, 2021. Image courtesy the artist.

fig.v Birds of No Nation, Shamsia Hassani’s Studio, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2016. Image courtesy the artist.

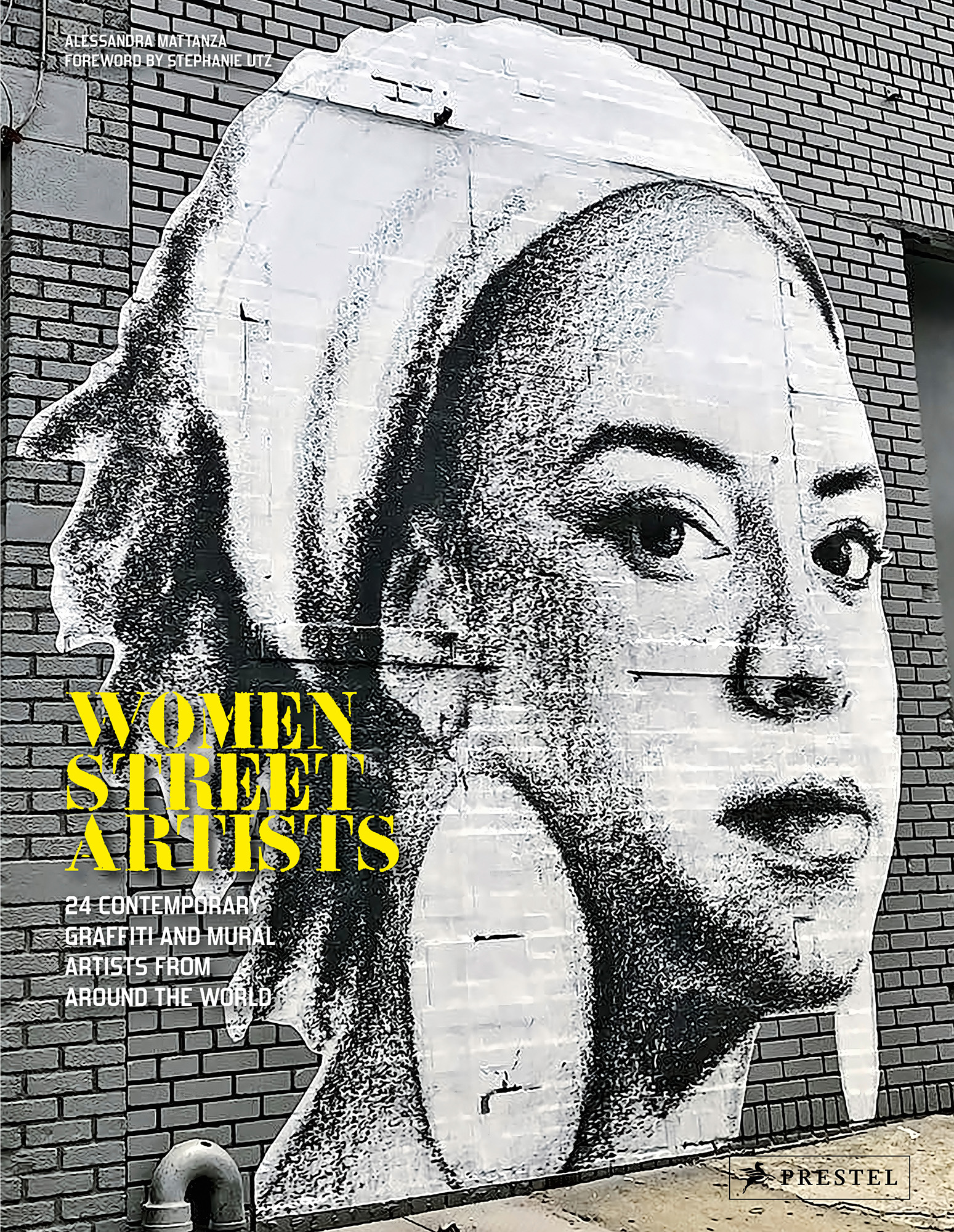

fig.vi Cover of Women Street Artists, featuring Brooklyn (2017) by Tatyana Fazlalizadeh. Image courtesy of Prestel.

publication date

30 November 2022

tags

Activism, Book, Anelí Chanquía, Colour, Crochet, Faith47, Camilla Falsini, Female, Feminism, Vanesa Galdeano, Gender, Graphics, Shamsia Hassani, Alessandra Mattanza, Medianeres, Mural, Olek, Politics, Prestel, Racism, Sexism, Street art

More information available at:

www.prestelpublishing.penguinrandomhouse.de/book/Women-Street-Artists/Alessandra-Mattanza/Prestel-com/e605291.rhd

images