White cube/black box: sculptural light from Germaine Kruip

& Anthony McCall

Two exhibitions in London use light as a medium to

sculpturally shape space & our relationship to it. At Tate Modern, Anthony

McCall’s exhibition Solid Light invites the viewer to interject their body

between light source & surface, co-curating the work & space. At

independent gallery The approach, Germain Kruip’s works in Real Time subtly

shift & shape the rooms they inhabit as theatrical, durational

intervention. Sam Moore entered the darkness of both to see the light,

finding connections between the two artists.

There is a crack, a crack in everything, that’s how the

light gets in. These lines, from the Leonard Cohen song Anthem, seem

to capture the ways in which being close to the light transforms both us and it:

the way it comes through treetops in stray, fractured beams, the shadows it can

cast along a wall. Our proximity to light transforms the space around us; what

it feels both to look at, and to inhabit. In his Tate Modern exhibition Solid

Light, Anthony McCall is able to take this feeling and turn it into something

corporeal.

![]()

![]()

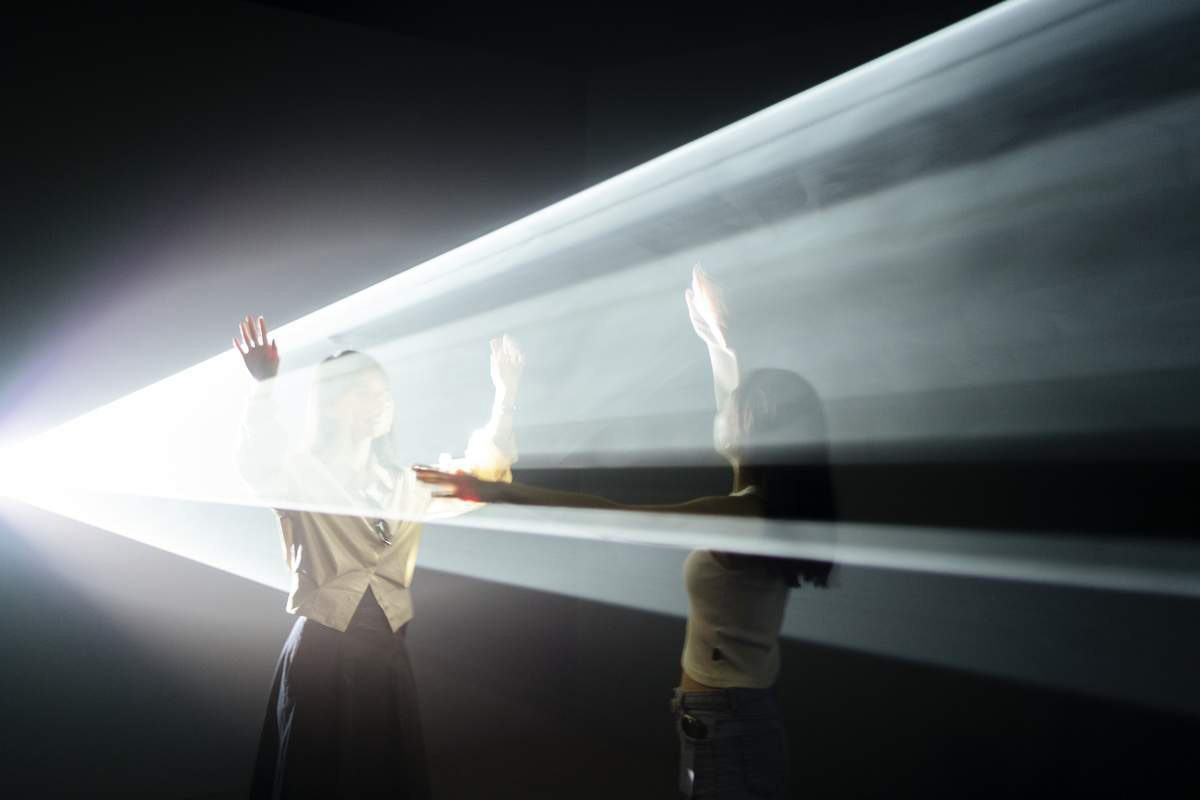

There are two sides to the works that make up Solid Light – the beams of light, and the black walls onto which shadows are cast. These shadows are at their most developed, most vivid, looking at the back side of the walls that McCall puts up around the gallery space, meaning that, if you’re standing away from the light, you’ll be able to see the impact that the presence of a human body can have on the surrounding space. The other side of this is the light itself, projected in a variety of shapes – a straight line, a zigzag, a circle – onto bare black walls. McCall invites us to go into the light.

The feeling is strange. While the light itself becomes all-consuming – it blocks out anything around it – it’s never blinding to look at. By being inside McCall beams of light, creating a sculpture between the body and the beam, the space itself transforms into pure brightness. Getting closer to the light, or first putting an errant hand or arm within it, is something that I approached tentative, uncertain; as if to step into the light would be to leave the room itself behind. This, in a way, is what happens – the light becomes the space, but it never feels solid; the edges of the beam like dust, something that the body can cut through.

In one part of the gallery is a wide beam, with a few cracks of light surrounding the reflective wall that it’s pointed at, illuminating it. I stand close to the source of the light, looking at my reflection in the mirror, pointing my phone camera at it. The light splits around my back, shooting light instead in beams shooting above my shoulders, and down below my hips. My presence transforms the space, and the light transforms my body.

![]()

![]()

![]()

But while McCall’s work offers a direct invitation to bring the viewer in, Germaine Kruip’s work in solo exhibition Real Time at The Approach gallery, offers a different relationship. Where McCall seems animated by the possibilities of the body, Kruip’s work is focused on drawing the attention of the eye, and asking it decode structures of light that are constantly transforming. And, in contrast to the black walls of McCall’s Solid Light, Real Time uses white walls. Each of these spaces offer something of a blank canvas: the black box of theatre, and the white walls of the gallery; each a space designed in tension with artifice and reality.

By presenting her work up against gallery walls, Kruip transforms them with lighting setups that feel inherently theatrical. In Ray (2025), a long beam of light flickers up against the wall, growing narrower and increasingly dark as time goes by; sometimes it fades away completely, before coming back to life. Looking at the stuttering transformations of Kruip’s work, it feels like the way light is shot through stained-glass windows, offering an uncertain possibility of salvation; or like the slashing mark of a dagger, cutting through fabric or a canvas. There’s something painterly in Kruip’s work, through the tension in which it seems to exist in a gallery space, and the way the shapes her lights form feel as if they could be right at home on a canvas.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

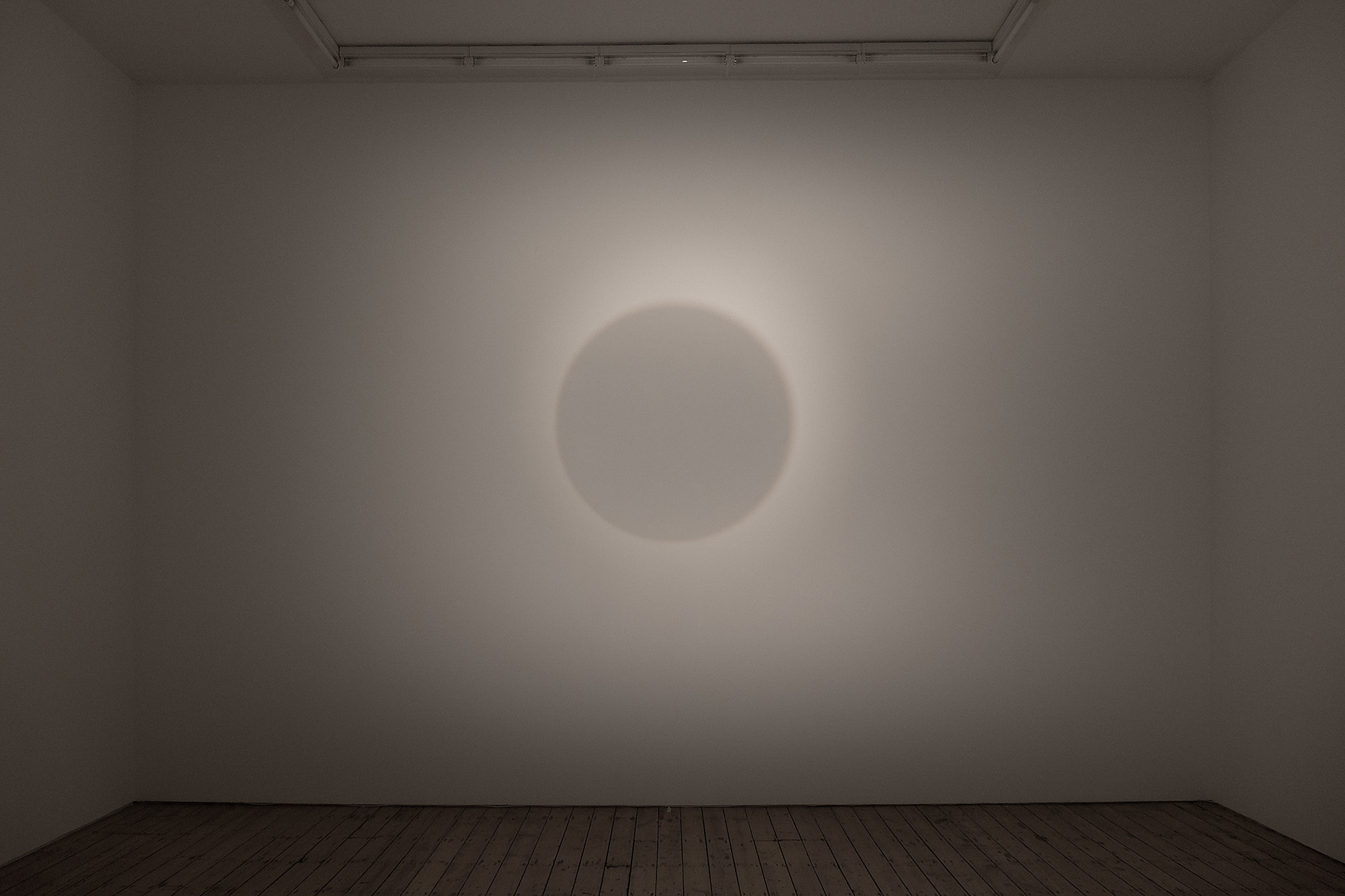

This feels particularly true for Horizon (2025). As the name suggests, this presents a circle of light that gradually moves down, fading into darkness like a setting sun. But more than that, it strikes me as the ghost of an abstract expressionist painting; the way that the light gathers, brightest in the centre, feels like a Mark Rothko’s colour field. Here, Kruip seems to use light as a way to capture the ghost of a painting, something that changes, even decays, in – as the title of the exhibition tells us – real time.

Both Kruip and McCall works use the ability of light to transform space as a way of engaging with other artistic forms. McCall turns the human body, and the strange spaces of light it occupies in his immersive work, into a kind of collaborative sculpture. His is fluid and changing with the movements of limbs, whereas Kruip’s work, with constant, gradual alterations, challenges the eyes with a series of associations that never remain static for long.

![]()

![]()

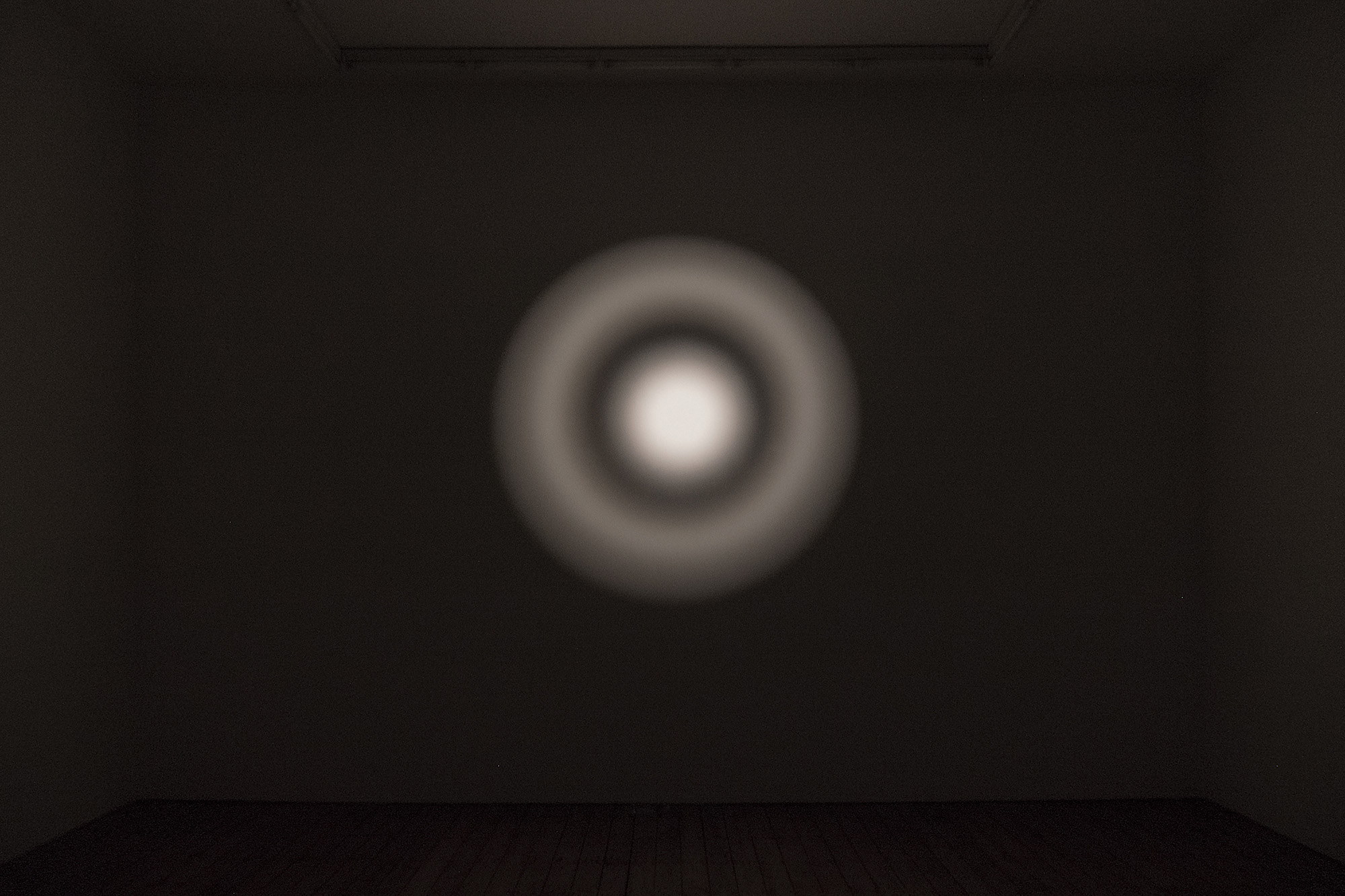

At the centre of Real Time is the aptly named Focal Point, a light projected onto a wall in the second gallery of The Approach. Slowly but surely, the circle of light goes through something of a narrative arc – darkness coming in from around the edges, the shape and form of it somehow constantly in flux. There are times where it looks like a human eye, or an eclipsed sun, an optical illusion taking on 3-D form. Again, this suggests a space beyond the gallery itself where this light might continue to exist, as if Kruip is illuminating something that has been hidden in plain sight all along.

While McCall does something similar in this creation of otherworldly space, in Solid Light it isn’t the light that does the becoming, but us; both artists create spaces that at first glance seem like the barebones skeleton for performance and art, transforming both it and us by exposing the cracks in everything, and letting the light in.

figs.i,ii

There are two sides to the works that make up Solid Light – the beams of light, and the black walls onto which shadows are cast. These shadows are at their most developed, most vivid, looking at the back side of the walls that McCall puts up around the gallery space, meaning that, if you’re standing away from the light, you’ll be able to see the impact that the presence of a human body can have on the surrounding space. The other side of this is the light itself, projected in a variety of shapes – a straight line, a zigzag, a circle – onto bare black walls. McCall invites us to go into the light.

The feeling is strange. While the light itself becomes all-consuming – it blocks out anything around it – it’s never blinding to look at. By being inside McCall beams of light, creating a sculpture between the body and the beam, the space itself transforms into pure brightness. Getting closer to the light, or first putting an errant hand or arm within it, is something that I approached tentative, uncertain; as if to step into the light would be to leave the room itself behind. This, in a way, is what happens – the light becomes the space, but it never feels solid; the edges of the beam like dust, something that the body can cut through.

In one part of the gallery is a wide beam, with a few cracks of light surrounding the reflective wall that it’s pointed at, illuminating it. I stand close to the source of the light, looking at my reflection in the mirror, pointing my phone camera at it. The light splits around my back, shooting light instead in beams shooting above my shoulders, and down below my hips. My presence transforms the space, and the light transforms my body.

figs, iii-v

But while McCall’s work offers a direct invitation to bring the viewer in, Germaine Kruip’s work in solo exhibition Real Time at The Approach gallery, offers a different relationship. Where McCall seems animated by the possibilities of the body, Kruip’s work is focused on drawing the attention of the eye, and asking it decode structures of light that are constantly transforming. And, in contrast to the black walls of McCall’s Solid Light, Real Time uses white walls. Each of these spaces offer something of a blank canvas: the black box of theatre, and the white walls of the gallery; each a space designed in tension with artifice and reality.

By presenting her work up against gallery walls, Kruip transforms them with lighting setups that feel inherently theatrical. In Ray (2025), a long beam of light flickers up against the wall, growing narrower and increasingly dark as time goes by; sometimes it fades away completely, before coming back to life. Looking at the stuttering transformations of Kruip’s work, it feels like the way light is shot through stained-glass windows, offering an uncertain possibility of salvation; or like the slashing mark of a dagger, cutting through fabric or a canvas. There’s something painterly in Kruip’s work, through the tension in which it seems to exist in a gallery space, and the way the shapes her lights form feel as if they could be right at home on a canvas.

figs.vi-ix

This feels particularly true for Horizon (2025). As the name suggests, this presents a circle of light that gradually moves down, fading into darkness like a setting sun. But more than that, it strikes me as the ghost of an abstract expressionist painting; the way that the light gathers, brightest in the centre, feels like a Mark Rothko’s colour field. Here, Kruip seems to use light as a way to capture the ghost of a painting, something that changes, even decays, in – as the title of the exhibition tells us – real time.

Both Kruip and McCall works use the ability of light to transform space as a way of engaging with other artistic forms. McCall turns the human body, and the strange spaces of light it occupies in his immersive work, into a kind of collaborative sculpture. His is fluid and changing with the movements of limbs, whereas Kruip’s work, with constant, gradual alterations, challenges the eyes with a series of associations that never remain static for long.

figs.x,xi

At the centre of Real Time is the aptly named Focal Point, a light projected onto a wall in the second gallery of The Approach. Slowly but surely, the circle of light goes through something of a narrative arc – darkness coming in from around the edges, the shape and form of it somehow constantly in flux. There are times where it looks like a human eye, or an eclipsed sun, an optical illusion taking on 3-D form. Again, this suggests a space beyond the gallery itself where this light might continue to exist, as if Kruip is illuminating something that has been hidden in plain sight all along.

While McCall does something similar in this creation of otherworldly space, in Solid Light it isn’t the light that does the becoming, but us; both artists create spaces that at first glance seem like the barebones skeleton for performance and art, transforming both it and us by exposing the cracks in everything, and letting the light in.

Germaine Kruip (b. 1970, Castricum, NL) lives and works

between Amsterdam and Brussels. She studied scenography at HKU (Utrecht, NL),

then pursued a Master’s in advanced research in theatre and dance studies at

DasArts (Amsterdam, NL), before enrolling in another Master’s program in Visual

Arts at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten (Amsterdam, NL).

Recent solo and two person exhibitions include: Two Circles,

Mirrored, The Approach, London, UK (2024); The Mirrored: Laura Grisi | Germaine

Kruip, The Approach, London, UK (2023); Rehearsal, Axel Vervoordt Gallery,

Wijnegem, Belgium (2022); Screenplay, Axel Vervoordt Gallery, Hong Kong (2021);

AFTER IMAGE, Gallery Baton, Seoul, Korea (2021).

Recent group exhibitions include: Artefact 2024:

At the still point of the turning world, STUK, Leuven, Belgium (2024);

Re-Inventing Piet. Mondrian and the Consequences, Kunstmuseum, Wolfsburg,

Germany, and Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen, Germany (2023); Mondriaan

Moves, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, Netherlands (2022).

www.germainekruip.com

Anthony McCall (b. 1946) lives and works in New York. His

solo exhibitions include Solid Light Works (2018) at The Hepworth Wakefield,

Wakefield; Five Minutes of Pure Sculpture (2012) at Hamburger Bahnhof –

Nationalgaleie der Gegenwart; Nu/Now: Anthony McCall (2009) at Moderna Museet,

Stockholm; Anthony McCall (2007-2008) at Serpentine Gallery, London; and

Anthony McCall: Films de Lumière Solide (2004) at Centre Pompidou/La Maison

Rouge, Foundation Antoine de Galbert, Paris.

McCall’s work has also featured in group exhibitions

including Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905-2016 (2016-17) Whitney

Museum, New York; About Time: Photography in a Moment of Change (2016) SFMOMA,

San Francisco; Light Show (2013) Hayward Gallery, London; Fifteen Weeks of Art

in Action (2012) Tate Modern, London; and On Line: Drawing Through the

Twentieth Century (2010-11) MOMA, New York.

McCall’s works are in the collections of Museum of Modern

Art, New York; Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris; Whitney

Museum of American Art, New York; Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Spain;

Auckland Art Gallery Toi O Tamaki, New Zealand; and Museum für Moderne Kunst,

Frankfurt.

www.anthonymccall.com

Sam Moore is a writer and editor. They are the author of All

my teachers died of AIDS (Pilot Press, 2020), and Long live the new flesh

(2022). Their criticism has been published by Frieze, The FT, The Guardian,

Hyperallergic, and more. They are one of the co-curators of TISSUE, a trans

reading series based in London.

McCall’s work has also featured in group exhibitions including Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905-2016 (2016-17) Whitney Museum, New York; About Time: Photography in a Moment of Change (2016) SFMOMA, San Francisco; Light Show (2013) Hayward Gallery, London; Fifteen Weeks of Art in Action (2012) Tate Modern, London; and On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century (2010-11) MOMA, New York.

McCall’s works are in the collections of Museum of Modern Art, New York; Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Spain; Auckland Art Gallery Toi O Tamaki, New Zealand; and Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt.

www.anthonymccall.com

Sam Moore is a writer and editor. They are the author of All

my teachers died of AIDS (Pilot Press, 2020), and Long live the new flesh

(2022). Their criticism has been published by Frieze, The FT, The Guardian,

Hyperallergic, and more. They are one of the co-curators of TISSUE, a trans

reading series based in London.

visit

Anthony McCall, Solid Light is showing at Tate

Modern, London, until 27 April.

Further details at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/anthony-mccall

Germaine Kruip, Real Time is on at The approach

gallery, London, until 05 April.

Further details available at: https://www.theapproach.co.uk/exhibitions/real-time

images

figs.i-v,xi

Installation view, Anthony McCall: Solid Light, Tate

Modern, 2024. All artworks by and © Anthony McCall. Photography © Tate (Josh

Croll) and courtesy the artist.

figs.i-5,x i Focal Point, 2025.

Eight architectural spotlights, 9 minute 15 second loop,

374 x 555 cm,

147 1/4 x 218 1/2 in. (AP-KRUIG-00256).

Courtesy of the artist and The Approach, London. Documentation by Maxime Fauconnier

publication date

07 February 2025

tags

Body, Dark, Leonard Cohen, Germaine Kruip, Light, Anthony McCall, Sam Moore, Shade, Shadow, Tate Modern, The approach

Further details at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/anthony-mccall

Germaine Kruip, Real Time is on at The approach gallery, London, until 05 April.

Further details available at: https://www.theapproach.co.uk/exhibitions/real-time