The country’s newest stone circle has been created in Luton

as a space for gathering & community

In a suburb of Luton, artist Matthew Rosier with a wide collaborative team of cultural organisations & local community members, has created the country’s newest stone circle. Will Jennings went along to Luton Henge to find a piece of land art that could become a space of gathering for thousands of years to come.

There’s little as romantic or historic in British landscape

than a stone circle. Standing since Neolithic times, both a physical and

gestural conversation between society, land, and proto-architecture, they act

as a poetic shorthand for a mysterious past that at once seems distant yet also

very present.

Physically, they are remarkably simple and immediately legible as forms – a circular arrangement of standing stones, situated both in landscape and in relation to celestial movement, with many circles aligned to the sun on solstice mornings. The most celebrated and recognisable – such as Avebury or Stonehenge (see 00017) are now iconic shorthand for British history, but there are thought to be around 1300 other stone circles in Britain and Ireland, not all as famous and ancient – the newest appearing only in the last few weeks!

![]()

![]()

![]()

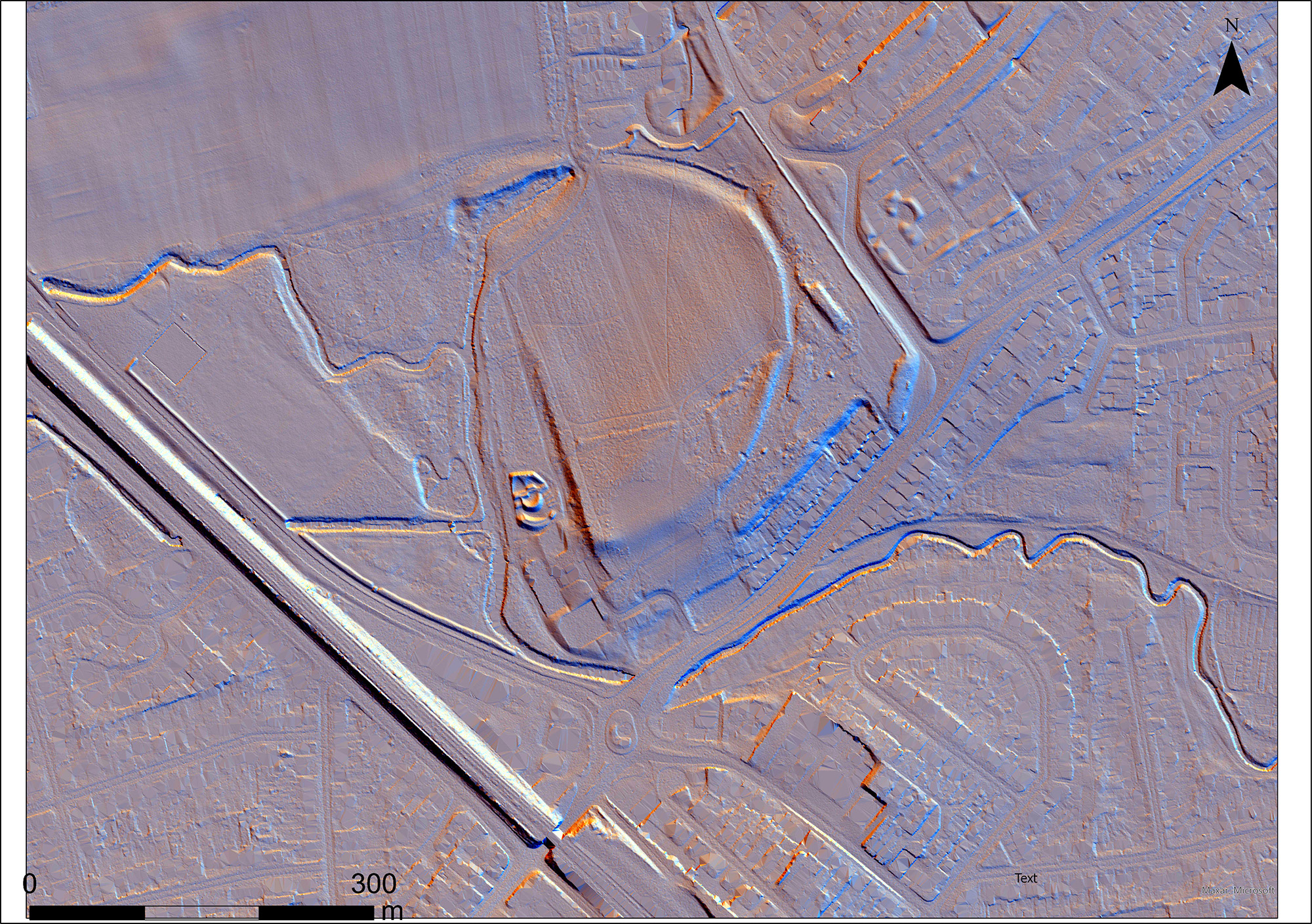

Leagrave is a suburb of Luton, Bedfordshire, once a small village sited on the river Lea until it got subsumed into the wider, growing town in the 1920s, though the first settlement in the area goes back to around 3000BC. Along the side of the river is Waulud’s Bank, a D-shaped embankment enclosing the source of the river covering 7 hectares, a structure that might have been used as an enclosure for cattle herding, may have had a spiritual or mystical importance, acted as a space for market exchange, or perhaps was simply one of the earliest known examples of largescale land art.

Today, there’s not a lot to see, having been flattened by centuries of agricultural use and excavated for gravel. It is, however, culturally fascinating, and was the impulse behind artist Matthew Rosier to choose the site for the country’s newest stone circle. Luton Henge is a permanent artwork, designed for and with the local community, that sits in its site as if it’s been present as long as the 1300 others scattered across the islands. It emerged from an open call for Nature Calling, a national arts project with the National Landscapes Association and Activate Performing Arts as executive producers, delivering six art projects and worked with six writers to work across the UK’s National Landscapes – the 46 areas of the country formally designated as Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Other installations – involving creatives including digital artist David Blandy, musician Gwyneth Herbert, and artist and writer Rob St. John – are temporary or ephemeral, covering pop-up installations, events, and podcasts. Matthew Rosier’s henge is not just the only permanent project on the list, he hopes it will become very permanent – “it’s basically to confuse future archaeologists”, the artist jokes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Rosier’s circle appears modest, but is meaningful. Formed of eight chunks of clunch, a chalky limestone rock historically used as a building material, the pieces were selected by the artist from nearby Totternhoe quarry, now largely closed but offering great conditions for a Wildlife Trust nature reserve, then carved down to the forms that encircle a mound today.

The site selected by Rosier for the rocks is also important, not only for its proximity to Waulud’s Bank. The rubble-filled topology of the site had been used by BMX bikers for a couple of decades, though the area had become overgrown and a little forgotten about by much of the local community. Rosier was commissioned by the Chilterns National Landscape, and the artist chose the location because it wasn’t one of area’s most glamourous or photogenic spots, but was a real plece with history and community, and was where the artists saw art could make an impact – not as a shiny bauble on a pedestal, but as a device to focus energies, engage local residents, and create a moment of curiosity in the public realm: “The idea was to treat it like a ready-made earthwork, as a response to the rubble piles already here and Waulud’s Bank – just to put our stone circle in a carved-out section in the middle as a gathering space – but to keep the BMX track functioning.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

This sense of gathering is important. The site is adjacent to Marsh House, a community space managed by Marsh Farm Outreach, initiated by former members of the legendary rave organisers Exodus Collective – named after the song by Bob Marley, a mural of whom covers one wall of the community centre. Over the 1990s, Exodus Collective were not only involved in organising some of the largest free raves, including a 1992 New Years Day event with over 10,000 attendees, they were also deeply interested in social organising, co-operative housing, environmental issues, and activism against authoritarianism.

Those formative energies are present in the organising and events that take place in and around Marsh House, and Rosier was keen that his work emerged from working with them rather as a public art project helicoptered in from outside. It was through workshops and conversations with this engaged community – Rosier realised his initially grand ambitions could be scaled down.

“I’d been over-designing it,” Rosier – who studied architecture at Oxford Brookes and UCL Bartlett before migrating into artmaking – said. “There was an interesting part of the public consultation, at an event people debated ‘what does a Luton henge look like?’ And what I got from it was that there wasn’t actually that much interest in what it looks like, its aesthetic, but people were more interested in ‘what is it for? How is it accessed? How is it used?’ Which I found very liberating in the end.”

It meant that Rosier, supported by producer Lucy Wood, could scale back grander ambitions and allow the simplicity of the stone circle as a gathering space and locality to be richer. “What was really important was the cultures and mixing that happens here – there is anecdotally not necessarily much mixing between certain communities – so I think the bigger aim here is how to create a space that feels truly accessible to different people. It doesn't feel overly one thing, religion, or culture.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

The community were also involved in the making of the site. Not only in discussions around the design and future, but helping with the huge amounts of labour involved to clear the site and then rake and hammer 10 tonnes of Totternhoe gravel to create the paths and central gathering space – “I’ve never done so much raking!” said Rosier, who created the work with the support of over 1,500 volunteer hours. Several wooden benches surround the stone circle, created with donated local timber then built over a week by community participants and Common Practice, a small Dorset-based architecture studio who focus on collaborative and low-carbon design.

A stone circle is a perfect device for such nuanced interpretation. There is so much about them still unknown, from the rituals or functions that they enabled to their methods of construction, and as such are perfect canvases for us to inject with our own meaning, concerns, and modes of congregation. The areas of Luton it sits at the centre of has large South Asian and Afro Caribbean communities as well we White British, and a stone circle is universal, abstract, and historic enough to be able to carry different meanings and interpretations. “One of the producers at Revoluton Arts, a cultural organisation based here, was saying an elderly Pakistani man visited and said that they reminded him of home, because in Pakistan there are white mountains in the Kashmiri regions.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

The site will now bed in, with grasses and wildflowers covering the mounds and ongoing public projects and events taking place around the stones. The site symbolically passed over from the artist to the community with a diverse day-long festival including a clay workshop, drumming, poetry, soul music, and even a bird rave.

All that is left to happen now is for the stone circle to age into its site, both naturally and culturally. The rubble mound and added stones offer perfect conditions for wildflowers and a management plan will be overseen by a legacy group, the Luton Henge Collective, which includes key local stakeholders. They will manage and maintain the site over its life and support the ongoing programme of events managed by Revoluton Arts.

the local community. Grass will regrow over where the works have taken place, the central circle will begin to become occupied by organised and informal events, gatherings, and parties, while BMXers will continue to circumnavigate the whole thing along their paths.

“We have no idea what happened in spaces like this, so that means people can do anything, and I think that's what's exciting.” Rosier wants to revisit the circle over coming months and years, but it’s now not his work, it belongs to the people of Leagrave, and says that “for me the artwork is seeing what happens here now it’s essentially a public space.” Humans have always had the impulse to gather, whether for solstices or raves, in venues or on public land, and Luton Henge is now a space where it can happen, for perhaps thousands of years to come.

![]()

Physically, they are remarkably simple and immediately legible as forms – a circular arrangement of standing stones, situated both in landscape and in relation to celestial movement, with many circles aligned to the sun on solstice mornings. The most celebrated and recognisable – such as Avebury or Stonehenge (see 00017) are now iconic shorthand for British history, but there are thought to be around 1300 other stone circles in Britain and Ireland, not all as famous and ancient – the newest appearing only in the last few weeks!

figs.i-iii

Leagrave is a suburb of Luton, Bedfordshire, once a small village sited on the river Lea until it got subsumed into the wider, growing town in the 1920s, though the first settlement in the area goes back to around 3000BC. Along the side of the river is Waulud’s Bank, a D-shaped embankment enclosing the source of the river covering 7 hectares, a structure that might have been used as an enclosure for cattle herding, may have had a spiritual or mystical importance, acted as a space for market exchange, or perhaps was simply one of the earliest known examples of largescale land art.

Today, there’s not a lot to see, having been flattened by centuries of agricultural use and excavated for gravel. It is, however, culturally fascinating, and was the impulse behind artist Matthew Rosier to choose the site for the country’s newest stone circle. Luton Henge is a permanent artwork, designed for and with the local community, that sits in its site as if it’s been present as long as the 1300 others scattered across the islands. It emerged from an open call for Nature Calling, a national arts project with the National Landscapes Association and Activate Performing Arts as executive producers, delivering six art projects and worked with six writers to work across the UK’s National Landscapes – the 46 areas of the country formally designated as Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Other installations – involving creatives including digital artist David Blandy, musician Gwyneth Herbert, and artist and writer Rob St. John – are temporary or ephemeral, covering pop-up installations, events, and podcasts. Matthew Rosier’s henge is not just the only permanent project on the list, he hopes it will become very permanent – “it’s basically to confuse future archaeologists”, the artist jokes.

figs.iv-vi

Rosier’s circle appears modest, but is meaningful. Formed of eight chunks of clunch, a chalky limestone rock historically used as a building material, the pieces were selected by the artist from nearby Totternhoe quarry, now largely closed but offering great conditions for a Wildlife Trust nature reserve, then carved down to the forms that encircle a mound today.

The site selected by Rosier for the rocks is also important, not only for its proximity to Waulud’s Bank. The rubble-filled topology of the site had been used by BMX bikers for a couple of decades, though the area had become overgrown and a little forgotten about by much of the local community. Rosier was commissioned by the Chilterns National Landscape, and the artist chose the location because it wasn’t one of area’s most glamourous or photogenic spots, but was a real plece with history and community, and was where the artists saw art could make an impact – not as a shiny bauble on a pedestal, but as a device to focus energies, engage local residents, and create a moment of curiosity in the public realm: “The idea was to treat it like a ready-made earthwork, as a response to the rubble piles already here and Waulud’s Bank – just to put our stone circle in a carved-out section in the middle as a gathering space – but to keep the BMX track functioning.”

figs.vii-ix

This sense of gathering is important. The site is adjacent to Marsh House, a community space managed by Marsh Farm Outreach, initiated by former members of the legendary rave organisers Exodus Collective – named after the song by Bob Marley, a mural of whom covers one wall of the community centre. Over the 1990s, Exodus Collective were not only involved in organising some of the largest free raves, including a 1992 New Years Day event with over 10,000 attendees, they were also deeply interested in social organising, co-operative housing, environmental issues, and activism against authoritarianism.

Those formative energies are present in the organising and events that take place in and around Marsh House, and Rosier was keen that his work emerged from working with them rather as a public art project helicoptered in from outside. It was through workshops and conversations with this engaged community – Rosier realised his initially grand ambitions could be scaled down.

“I’d been over-designing it,” Rosier – who studied architecture at Oxford Brookes and UCL Bartlett before migrating into artmaking – said. “There was an interesting part of the public consultation, at an event people debated ‘what does a Luton henge look like?’ And what I got from it was that there wasn’t actually that much interest in what it looks like, its aesthetic, but people were more interested in ‘what is it for? How is it accessed? How is it used?’ Which I found very liberating in the end.”

It meant that Rosier, supported by producer Lucy Wood, could scale back grander ambitions and allow the simplicity of the stone circle as a gathering space and locality to be richer. “What was really important was the cultures and mixing that happens here – there is anecdotally not necessarily much mixing between certain communities – so I think the bigger aim here is how to create a space that feels truly accessible to different people. It doesn't feel overly one thing, religion, or culture.”

figs.x-xii

The community were also involved in the making of the site. Not only in discussions around the design and future, but helping with the huge amounts of labour involved to clear the site and then rake and hammer 10 tonnes of Totternhoe gravel to create the paths and central gathering space – “I’ve never done so much raking!” said Rosier, who created the work with the support of over 1,500 volunteer hours. Several wooden benches surround the stone circle, created with donated local timber then built over a week by community participants and Common Practice, a small Dorset-based architecture studio who focus on collaborative and low-carbon design.

A stone circle is a perfect device for such nuanced interpretation. There is so much about them still unknown, from the rituals or functions that they enabled to their methods of construction, and as such are perfect canvases for us to inject with our own meaning, concerns, and modes of congregation. The areas of Luton it sits at the centre of has large South Asian and Afro Caribbean communities as well we White British, and a stone circle is universal, abstract, and historic enough to be able to carry different meanings and interpretations. “One of the producers at Revoluton Arts, a cultural organisation based here, was saying an elderly Pakistani man visited and said that they reminded him of home, because in Pakistan there are white mountains in the Kashmiri regions.”

figs.xiii-xv

The site will now bed in, with grasses and wildflowers covering the mounds and ongoing public projects and events taking place around the stones. The site symbolically passed over from the artist to the community with a diverse day-long festival including a clay workshop, drumming, poetry, soul music, and even a bird rave.

All that is left to happen now is for the stone circle to age into its site, both naturally and culturally. The rubble mound and added stones offer perfect conditions for wildflowers and a management plan will be overseen by a legacy group, the Luton Henge Collective, which includes key local stakeholders. They will manage and maintain the site over its life and support the ongoing programme of events managed by Revoluton Arts.

the local community. Grass will regrow over where the works have taken place, the central circle will begin to become occupied by organised and informal events, gatherings, and parties, while BMXers will continue to circumnavigate the whole thing along their paths.

“We have no idea what happened in spaces like this, so that means people can do anything, and I think that's what's exciting.” Rosier wants to revisit the circle over coming months and years, but it’s now not his work, it belongs to the people of Leagrave, and says that “for me the artwork is seeing what happens here now it’s essentially a public space.” Humans have always had the impulse to gather, whether for solstices or raves, in venues or on public land, and Luton Henge is now a space where it can happen, for perhaps thousands of years to come.

fig.xvi

Matthew

Rosier (b.1990) is an artist who creates public artworks with communities across

the UK. His practice involves the public in both the creation process and

finished work, creating immersive installations that connect people with their

shared heritage, landscapes and each other.

Previous

projects include Shadowing (2014), a series of streetlights that record and

replay shadows; The Lost Palace (2016), an interactive experience that overlaid

a past palace onto the streets of London; and Pontefract Giants (2021), which

used projection and sound to transform trees into ancestral giants.

Matthew's

work has been installed in public spaces in London, Paris, Austin, and Tokyo;

commissioned by the councils of Westminster, Southwark, Rotherham, Doncaster,

Wakefield, Cheshire East and the City of London; shown at the Design Museum and

the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; nominated as one of the Design

Museum’s Designs of the Year; and awarded the Active Public Space Award, the

London Contemporary Art Prize Public Vote Award, and the Museum + Heritage

Innovation Award. Matthew studied architecture at Oxford Brookes and the

Bartlett, University College London, and was a resident at Fabrica, a design

research centre in Italy.

www.matthewrosier.com

Nature Calling is the first

national programme of new art commissions by the National Landscapes

Association and Activate Performing Arts.

The National Landscapes

Association is the membership body for the UK's 46 National Landscapes, iconic

places and familiar sights like the chocolate box villages of the Cotswolds;

Willy Lott's farm - the scene of Constable's Hay Wain painting; and Pendle

Hill, iconic in north west England as the backdrop for the legendary Pendle

witches. They are all different, dynamic, living communities with distinct

heritage and culture.

In 2023, The National Landscapes

Association, working with Activate Performing Arts secured funding from Arts

Council England and Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs (Defra)

(as part of the Protected Landscapes Partnership) and National Landscapes in

England to deliver Nature Calling. Nature Calling is designed to amplify new

voices and create innovative artwork in collaboration with communities close to

National Landscapes and building to a national 'season' sharing the work

between May and October 2025.

The six regional National

Landscapes hubs are: Chilterns (with Revoluton Arts), Dorset (with Activate

Performing Arts), Forest of Bowland (with Blaze Arts and Lancaster Arts),

Lincolnshire Wolds (with Magna Vitae), Mendip Hills (with Super Culture) and Surrey

Hills (with Surrey Hills Arts). All 46 National Landscapes across England are

involved.

www.naturecalling.org.uk

The Chilterns National Landscape

is a designated area of outstanding natural beauty and covers 833 square

kilometres across Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.

The many rare species and habitats, rolling chalk hills, magnificent beechwoods

and wildflower-rich hills are just some of the special features of the

Chilterns, which are enjoyed by local people and visitors alike.

www.chilterns.org.uk

National Landscapes are areas of

countryside in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland, that have been designated

for conservation due to its significant landscape value. Areas are designated

in recognition of their national importance by the relevant public body:

Natural England, Natural Resources Wales, and the Northern Ireland Environment

Agency, respectively. In place of National Landscapes, Scotland uses the

similar national scenic area (NSA) designation.

The National Parks and Access to

the Countryside Act 1949 is the Act of the Parliament that provided the

framework for the creation of National Parks and National Landscapes (formerly

Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs)) in England and Wales, and also

addressed public rights of way and access to open land.

National Landscapes offer a

uniquely integrated perspective in decisions about land use: convening

conversations, bringing people together, and enabling a sustainable balance of

priorities for nature, climate, people and place. National Landscape

Partnerships own no land, so their work is delivered by convening strong

networks with landowners, farmers and partner organisations, working together

to plan projects, and secure funding to deliver them. The National Landscapes

Association is the non-profit membership organisation representing the UK’s

National Landscapes.

www.national-landscapes.org.uk

The National Landscapes Association is the membership body for the UK's 46 National Landscapes, iconic places and familiar sights like the chocolate box villages of the Cotswolds; Willy Lott's farm - the scene of Constable's Hay Wain painting; and Pendle Hill, iconic in north west England as the backdrop for the legendary Pendle witches. They are all different, dynamic, living communities with distinct heritage and culture.

In 2023, The National Landscapes Association, working with Activate Performing Arts secured funding from Arts Council England and Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) (as part of the Protected Landscapes Partnership) and National Landscapes in England to deliver Nature Calling. Nature Calling is designed to amplify new voices and create innovative artwork in collaboration with communities close to National Landscapes and building to a national 'season' sharing the work between May and October 2025.

The six regional National Landscapes hubs are: Chilterns (with Revoluton Arts), Dorset (with Activate Performing Arts), Forest of Bowland (with Blaze Arts and Lancaster Arts), Lincolnshire Wolds (with Magna Vitae), Mendip Hills (with Super Culture) and Surrey Hills (with Surrey Hills Arts). All 46 National Landscapes across England are involved.

www.naturecalling.org.uk

The Chilterns National Landscape

is a designated area of outstanding natural beauty and covers 833 square

kilometres across Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.

The many rare species and habitats, rolling chalk hills, magnificent beechwoods

and wildflower-rich hills are just some of the special features of the

Chilterns, which are enjoyed by local people and visitors alike.

www.chilterns.org.uk

National Landscapes are areas of

countryside in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland, that have been designated

for conservation due to its significant landscape value. Areas are designated

in recognition of their national importance by the relevant public body:

Natural England, Natural Resources Wales, and the Northern Ireland Environment

Agency, respectively. In place of National Landscapes, Scotland uses the

similar national scenic area (NSA) designation.

The National Parks and Access to

the Countryside Act 1949 is the Act of the Parliament that provided the

framework for the creation of National Parks and National Landscapes (formerly

Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs)) in England and Wales, and also

addressed public rights of way and access to open land.

National Landscapes offer a

uniquely integrated perspective in decisions about land use: convening

conversations, bringing people together, and enabling a sustainable balance of

priorities for nature, climate, people and place. National Landscape

Partnerships own no land, so their work is delivered by convening strong

networks with landowners, farmers and partner organisations, working together

to plan projects, and secure funding to deliver them. The National Landscapes

Association is the non-profit membership organisation representing the UK’s

National Landscapes.

www.national-landscapes.org.uk

The National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 is the Act of the Parliament that provided the framework for the creation of National Parks and National Landscapes (formerly Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs)) in England and Wales, and also addressed public rights of way and access to open land.

National Landscapes offer a uniquely integrated perspective in decisions about land use: convening conversations, bringing people together, and enabling a sustainable balance of priorities for nature, climate, people and place. National Landscape Partnerships own no land, so their work is delivered by convening strong networks with landowners, farmers and partner organisations, working together to plan projects, and secure funding to deliver them. The National Landscapes Association is the non-profit membership organisation representing the UK’s National Landscapes.

www.national-landscapes.org.uk

Activate exists to promote,

support and produce performing arts projects in our communities. Bringing

world-class events to unexpected places, like town centres, village squares,

beaches and hilltops. And we’ve been doing it for over 30 years. In everything

we do, we have just two rules: Anything’s possible and everyone’s invited.

Our aim is it break down barriers

and reach the widest possible audiences, while celebrating our natural

landscape and sense of place. Supporting our performing arts community is at

the heart of everything we do. We bring people together, offer advice, and

provide access to learning and resources. We’re here to help creatives at all

levels on their journey towards creating outstanding, inspiring work.

As one of Arts Council England’s

National Portfolio Organisations, we receive regular funding to initiate,

develop and sustain a range of dance, theatre and outdoor arts opportunities

for the people of Dorset and the South West. We are also core funded by Dorset

Council and BCP Council. As a not-for-profit organisation, we work in many ways

and with many partners. Our team may be small, but we’re agile, expert and very

well connected, with a will to make things happen.

www.activateperformingarts.org.uk

Activate exists to promote,

support and produce performing arts projects in our communities. Bringing

world-class events to unexpected places, like town centres, village squares,

beaches and hilltops. And we’ve been doing it for over 30 years. In everything

we do, we have just two rules: Anything’s possible and everyone’s invited.

Our aim is it break down barriers

and reach the widest possible audiences, while celebrating our natural

landscape and sense of place. Supporting our performing arts community is at

the heart of everything we do. We bring people together, offer advice, and

provide access to learning and resources. We’re here to help creatives at all

levels on their journey towards creating outstanding, inspiring work.

As one of Arts Council England’s

National Portfolio Organisations, we receive regular funding to initiate,

develop and sustain a range of dance, theatre and outdoor arts opportunities

for the people of Dorset and the South West. We are also core funded by Dorset

Council and BCP Council. As a not-for-profit organisation, we work in many ways

and with many partners. Our team may be small, but we’re agile, expert and very

well connected, with a will to make things happen.

www.activateperformingarts.org.uk

Revoluton Arts is an arts charity

organisation based in Luton. It matches artists, communities, and ideas to

create high-quality, ambitious creative projects in Luton and with other places

like it. Revoluton’s mission is to inspire creative ambition, collective social

impact, and world-class creativity right in the heart of communities.

Revoluton is committed to

communities taking the lead in creative projects, inspiring people to be more

creative, and engaging people where they live, shop and work. Art projects are

co-created to resonate and be relevant to local audiences. Revoluton’s projects

reflect the diversity of the communities it works in, from the documentary film

Made in Luton set in Bury Park, Luton, to large-scale outdoor spectaculars in

Luton's town centre like Lampadophores in 2023. It has a particular focus on

working with Luton-based creators aged 16-30 to develop their creative skills

and ambition.

Revoluton’s funders, partners,

and collaborators share their beliefs and empower the organisation to make an

impact. Revoluton (formerly a CIC), now a charity, has been part of Arts

Council England’s Creative People and Places Programme since 2015 and was one

of over 100 US and UK organisations selected for the Bloomberg Philanthropies

Digital Accelerator programme.

www.revolutonarts.com

Revoluton Arts is an arts charity

organisation based in Luton. It matches artists, communities, and ideas to

create high-quality, ambitious creative projects in Luton and with other places

like it. Revoluton’s mission is to inspire creative ambition, collective social

impact, and world-class creativity right in the heart of communities.

Revoluton is committed to

communities taking the lead in creative projects, inspiring people to be more

creative, and engaging people where they live, shop and work. Art projects are

co-created to resonate and be relevant to local audiences. Revoluton’s projects

reflect the diversity of the communities it works in, from the documentary film

Made in Luton set in Bury Park, Luton, to large-scale outdoor spectaculars in

Luton's town centre like Lampadophores in 2023. It has a particular focus on

working with Luton-based creators aged 16-30 to develop their creative skills

and ambition.

Revoluton’s funders, partners,

and collaborators share their beliefs and empower the organisation to make an

impact. Revoluton (formerly a CIC), now a charity, has been part of Arts

Council England’s Creative People and Places Programme since 2015 and was one

of over 100 US and UK organisations selected for the Bloomberg Philanthropies

Digital Accelerator programme.

www.revolutonarts.com

Will

Jennings is

a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities,

architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The

Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches

history & theory at UCL Bartlett & is director of UK cultural charity

Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

Will

Jennings is

a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities,

architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The

Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches

history & theory at UCL Bartlett & is director of UK cultural charity

Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

Luton Henge was commissioned by the Chilterns National Landscape for Nature Calling and produced by Luton arts charity Revoluton Arts. Executive producers are the National Landscapes Association and Activate Performing Arts. It is supported by Arts Council England and DEFRA.

Luton Henge can be visited by the public at any time. It can be found in Leagrave, Luton, a short walk from Leagrave station: Google Maps

images

fig.i Chalk standing stone - Luton Henge by Matthew Rosier. Photo

©

Roo Lewis for Nature Calling 2025

fig.ii Artist Matthew Rosier stands at the Henge - Luton Henge by Matthew Rosier. Photo

©

Roo Lewis for Nature Calling 2025

figs.iii,ix,xi,xiv Luton Henge. Matthew Rosier, Nature Calling. Photo

©

Ray Chan

fig.iv River Lea, Leagrave Marsh Farm Luton. Photo

©

Chilterns National Landscape.

fig.v Lidar of Waulud’s Bank + Henge site. Chilterns Conservation Board

fig.vi Luton Henge build in progress, Matthew Rosier. Image

©

Matthew Rosier for Nature Calling 2025.

fig.vii Bikers 02. Luton Henge by Matthew Rosier. Photo

©

Roo Lewis for Nature Calling 2025.

fig.viii Members of Marsh Farm Outreach (Formerly Exodus Collective) - Luton Henge by Matthew Rosier. Photo

©

Roo Lewis for Nature Calling 2025

figs.x,xii,xvi Luton Henge in progress, Matthew Rosier. Image

©

Matthew Rosier for Nature Calling.

fig.xiii Lower Res. Luton Henge, Matthew Rosier. Photo Roo Lewis

©

Nature Calling 2025.

fig.xv Charred Luton Henge bench with Marsh Farm residential towers in background - Luton Henge by Matthew Rosier. Photo

©

Roo Lewis for Nature Calling 2025

publication date

06 August 2025

tags

Activate Performing Arts, BMX, Clunch, Common Practice, Community, Exodus Collective, Will Jennings, Land art, Leagrave, Luton, Luton Henge, Marsh Farm Outreach, Matthew Rosier, National Landscape Association, Nature Calling, Neolithic, Stone circle, Stonehenge, Totternhoe quarry, Waulud’s Bank, Wildflowers, Lucy Wood

Luton Henge can be visited by the public at any time. It can be found in Leagrave, Luton, a short walk from Leagrave station: Google Maps