Stanley Greenberg’s photographs of a changing New York

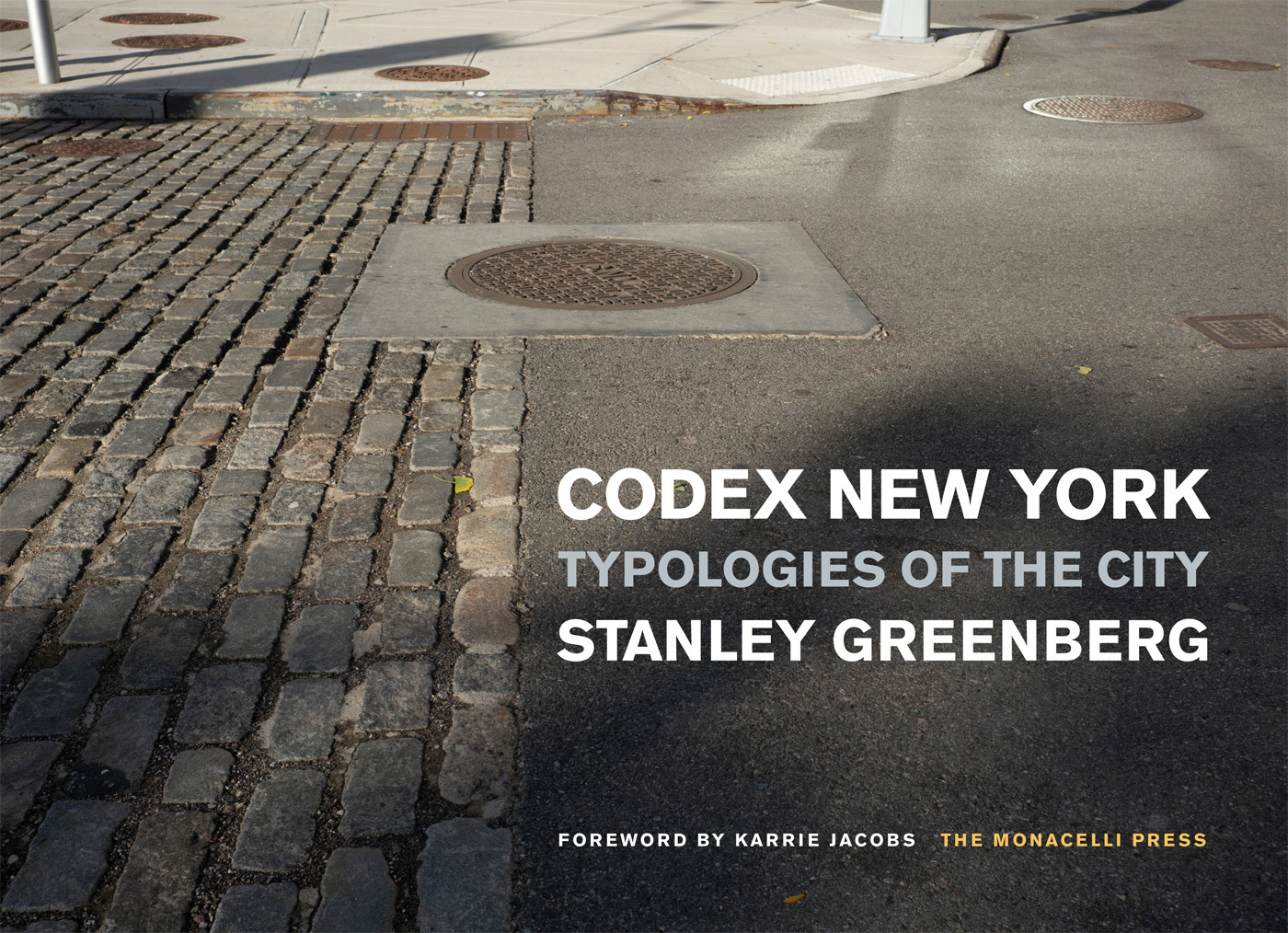

In his book Codex New York, photographer and author Stanley Greenberg captures timeless and true moments of New York through his consideration of the city through his lens and typologies.

Codex New York breaks away from the grid of New York, and instead considers the city through a system of typologies. Stanley Greenberg used his lens to observe the city through his categories including geology, alleys, relics, water supply, and construction. In this edited extract of her forward to the 2019 book - reproduced with kind permission of the author and The Monacelli Press - writer and educator Karrie Jacobs reflects on Greenberg’s methodology and poetically considers how looking and understanding can protect a city from adverse change.

Stanley Greenberg’s methodology is a simple one: he walks around with his eyes open and he notices the things that are right in front of him, things that most of us are too distracted to see. Greenberg’s photos, for example, document the fact that myriad older New York buildings tend to lean on their neighbors and, when those adjacent buildings are demolished, require shockingly primitive-looking buttresses to forestall structural failure. And he compulsively documents Manhattan’s irregularities, the spots where the borough’s defining grid—a smooth plain marked by streets crossing at right angles—becomes unexpectedly sharp-cornered or hilly.

![]()

![]()

![]()

I’m sympathetic to this strategy because I practice it myself. As a writer and as a teacher, I spend a lot of my time urging people to look at the city around them. In particular, I like to send graduate students out into the streets to search for examples of ephemeral qualities like truth or beauty. Why? Because the muzzy, conceptual nature of the assignment focuses their awareness on the streetscape. It forces the students to look harder at absolutely everything. And the city isn’t dull at all, if you pay attention.

Additionally, it increasingly seems pretty obvious that the dullness of the city is commensurate to the interestingness of the glowing rectangle we habitually hold in front of our faces. The smart phone is a mind-suck of historic proportions and as we focus on it, checking the analytics of our most recent selfie or tracking the whereabouts of an ex-boyfriend, the city around us fades. It loses definition. It becomes a sketchily articulated background to the brilliant electronic foreground. It’s not just that the city somehow turned into a gilded habitat for rich people (who don’t even truly live here) when we weren’t paying attention; the transformation happened specifically because we weren’t paying attention.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cause and effect become obvious when you read pre-iPhone narratives about the streetscape. The classic example is Ian Frazier’s 1990 New Yorker essay about Canal Street. “Near the corner of Canal and Broadway is a store that used to sell luggage, jewelry, and takeout Chinese food but now just sells luggage. Another store sells plastic sheeting and imitation classical statues made of fiberglass. The nymphs and dryads and goddesses are displayed out front, chained to a security gate with bicycle locks around their necks.” Frazier was observing closely and the city responded by yielding a mother lode of specificity. Today, many of the blocks he described almost three decades ago have been methodically scrubbed by what the real estate industry thinks of as “highest and best use.”

While there are economic and political reasons that kind of thing happens, an important and rarely considered cause is that we’ve averted our eyes. As philosopher George Berkeley once said, “To be is to be perceived.” And, presumably, the inverse is true. What is no longer perceived ceases, in any meaningful way, to be.

As his fundamental philosophy as a photographer, Greenberg perceives. It’s what he does. His photography is about being deeply aware of the city around us, even noticing and documenting those things that lay beneath the city’s surface or outside its boundaries that, nonetheless, allow New York City to exist.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Codex emerged from a completely different project. Greenberg was searching for “big empty spaces where buildings had been torn down.” If you know New York—or any city, really—you understand that demolition can be revelatory. The denser the setting, the more things appear when a building suddenly vanishes. At minimum, razing one building uncovers the walls from the adjoining buildings that had been obscured for decades, perhaps centuries. Particularly in midtown Manhattan, the removal of a building creates something that works like a plaza. Where you can suddenly gain a perspective—maybe something as simple as the sun hitting the sidewalk at a new angle—that didn’t exist before.

Greenberg originally set out to find and document those absences that we usually come upon by chance. He started at the Battery and began working his way north from there. “I took the train in from Brooklyn, got out at the Customs House and started walking.” His idea was that he’d document the gaps with a digital camera and return later to frame his shots with a large-format camera. “I had a Google map of the neighborhood in hand, ready to mark the empty spaces. Within a half hour knew I was going to walk every block on the island.”

What was truly captivating, however, as Greenberg covered the map, street by street, was “building typologies and infrastructure.” He soon realized that “it was a different project than I originally thought it was.” Sticking with the smaller, more versatile digital camera he set out to document features that explain “what the city is made of and what it takes to make it work. ... I thought about what made up the city, the history, the layers, the unseen, places I had been that were restricted.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

Some features, he noticed, were everywhere—like playgrounds and parking lots—and others were concentrated in just one area. For example, his depictions of “visible geology and topography,” in which familiar urban objects, like subway station entrances, coexist with startling rock formations, are mostly way uptown in the northern reaches of Manhattan.

Greenberg isn’t just speaking to architects, planners, or designers, or even photographers or the authors of long, dispirited assessments of the fate of the city. His audience is more universal. His message is more catholic. What Codex New York reveals isn’t mysterious at all. His photos are an argument for seeing with determination, for seeking out what makes New York City unique, for understanding that we are surrounded by a work of boundless ingenuity, passion, messy vitality, and, sometimes, genius. It’s a collection of photographs that states unequivocally that our job, as human beings, is to see what’s in front of us, and to consciously, willfully, observe.

Stanley Greenberg’s methodology is a simple one: he walks around with his eyes open and he notices the things that are right in front of him, things that most of us are too distracted to see. Greenberg’s photos, for example, document the fact that myriad older New York buildings tend to lean on their neighbors and, when those adjacent buildings are demolished, require shockingly primitive-looking buttresses to forestall structural failure. And he compulsively documents Manhattan’s irregularities, the spots where the borough’s defining grid—a smooth plain marked by streets crossing at right angles—becomes unexpectedly sharp-cornered or hilly.

I’m sympathetic to this strategy because I practice it myself. As a writer and as a teacher, I spend a lot of my time urging people to look at the city around them. In particular, I like to send graduate students out into the streets to search for examples of ephemeral qualities like truth or beauty. Why? Because the muzzy, conceptual nature of the assignment focuses their awareness on the streetscape. It forces the students to look harder at absolutely everything. And the city isn’t dull at all, if you pay attention.

Additionally, it increasingly seems pretty obvious that the dullness of the city is commensurate to the interestingness of the glowing rectangle we habitually hold in front of our faces. The smart phone is a mind-suck of historic proportions and as we focus on it, checking the analytics of our most recent selfie or tracking the whereabouts of an ex-boyfriend, the city around us fades. It loses definition. It becomes a sketchily articulated background to the brilliant electronic foreground. It’s not just that the city somehow turned into a gilded habitat for rich people (who don’t even truly live here) when we weren’t paying attention; the transformation happened specifically because we weren’t paying attention.

Cause and effect become obvious when you read pre-iPhone narratives about the streetscape. The classic example is Ian Frazier’s 1990 New Yorker essay about Canal Street. “Near the corner of Canal and Broadway is a store that used to sell luggage, jewelry, and takeout Chinese food but now just sells luggage. Another store sells plastic sheeting and imitation classical statues made of fiberglass. The nymphs and dryads and goddesses are displayed out front, chained to a security gate with bicycle locks around their necks.” Frazier was observing closely and the city responded by yielding a mother lode of specificity. Today, many of the blocks he described almost three decades ago have been methodically scrubbed by what the real estate industry thinks of as “highest and best use.”

While there are economic and political reasons that kind of thing happens, an important and rarely considered cause is that we’ve averted our eyes. As philosopher George Berkeley once said, “To be is to be perceived.” And, presumably, the inverse is true. What is no longer perceived ceases, in any meaningful way, to be.

As his fundamental philosophy as a photographer, Greenberg perceives. It’s what he does. His photography is about being deeply aware of the city around us, even noticing and documenting those things that lay beneath the city’s surface or outside its boundaries that, nonetheless, allow New York City to exist.

Codex emerged from a completely different project. Greenberg was searching for “big empty spaces where buildings had been torn down.” If you know New York—or any city, really—you understand that demolition can be revelatory. The denser the setting, the more things appear when a building suddenly vanishes. At minimum, razing one building uncovers the walls from the adjoining buildings that had been obscured for decades, perhaps centuries. Particularly in midtown Manhattan, the removal of a building creates something that works like a plaza. Where you can suddenly gain a perspective—maybe something as simple as the sun hitting the sidewalk at a new angle—that didn’t exist before.

Greenberg originally set out to find and document those absences that we usually come upon by chance. He started at the Battery and began working his way north from there. “I took the train in from Brooklyn, got out at the Customs House and started walking.” His idea was that he’d document the gaps with a digital camera and return later to frame his shots with a large-format camera. “I had a Google map of the neighborhood in hand, ready to mark the empty spaces. Within a half hour knew I was going to walk every block on the island.”

What was truly captivating, however, as Greenberg covered the map, street by street, was “building typologies and infrastructure.” He soon realized that “it was a different project than I originally thought it was.” Sticking with the smaller, more versatile digital camera he set out to document features that explain “what the city is made of and what it takes to make it work. ... I thought about what made up the city, the history, the layers, the unseen, places I had been that were restricted.”

Some features, he noticed, were everywhere—like playgrounds and parking lots—and others were concentrated in just one area. For example, his depictions of “visible geology and topography,” in which familiar urban objects, like subway station entrances, coexist with startling rock formations, are mostly way uptown in the northern reaches of Manhattan.

Greenberg isn’t just speaking to architects, planners, or designers, or even photographers or the authors of long, dispirited assessments of the fate of the city. His audience is more universal. His message is more catholic. What Codex New York reveals isn’t mysterious at all. His photos are an argument for seeing with determination, for seeking out what makes New York City unique, for understanding that we are surrounded by a work of boundless ingenuity, passion, messy vitality, and, sometimes, genius. It’s a collection of photographs that states unequivocally that our job, as human beings, is to see what’s in front of us, and to consciously, willfully, observe.

Stanley Greenberg is a Brooklyn-based photographer and author of numerous books, including Invisible New York: The Hidden Infrastructure of the City (1998), Waterworks: A Photographic Journey Through New York’s Hidden Water System

(2003), Architecture Under Construction (2010), and Time Machines (2011). His photographs are held in prominent collections,

including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the New York Public Library, the Yale University Art Gallery, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others. Greenberg has received a

fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, as well as grants from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the

National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, and the New York State Council on the Arts.

www.stanleygreenberg.org

www.instagram.com/stanleygreenberg/

Karrie Jacobs is a professional observer of the man-made landscape. She is a faculty member at the School of Visual Arts’ MA program in Design Research, Writing, and Criticism, where

she teaches students how to understand and interpret the design-rich environment all around them. She was the

founding editor-in-chief of Dwell and the founding executive editor of Benetton’s Colors. She is the author of The Perfect $100,000 House (2006) and co-author of Angry Graphics (1992)..

www.karriejacobs.com

book available at

Codex New York available from The Monacelli Press at: www.monacellipress.com/book/codex-new-york/

images

All photographs © Stanley Greenberg

publication date

13 February 2022

tags

Architecture, City, Codex New York, Development, Stanley Greenberg, Karrie Jacobs, Landscape, Monacelli Press. New York, Photography, Urban

publication date

13 February 2022

tags

Architecture, City, Codex New York, Development, Stanley Greenberg, Karrie Jacobs, Landscape, Monacelli Press. New York, Photography, Urban

fig.i-iii