Meeting zombies by the fountain: George Romero’s shopping mall

George Romero’s 1978 film Dawn of the Dead remains a mainstay of the zombie horror film genre, but alongside the main protagonists there is one standout star - the Monroeville Mall in Pennsylvania. In this extract from her new book Meet Me By The Fountain: An Inside History Of The Mall, Alexandra Lange explores the afterlife of both suburban shopping malls and those who dwell within.

Why do zombies go to

the mall?

This question is asked and answered in George Romero's 1978 cult classic Dawn of the Dead, the second part of a planned horror trilogy. Four survivors of a zombie attack steal a TV helicopter and head north, making for Canada. As they chopper over fields and roads, they find that the virus has spread past the bounds of the city. Every open space includes dark figures that stagger toward some undefined goal. Low on fuel and sleep, the escapees reach a vast, empty parking lot. "What the hell is it?" someone asks, as if encountering the ruin of an ancient civilization. "Looks like a shopping center, one of those big indoor malls" is the reply.

Although the mall was unrecognizable from the air, once they land the helicopter on the roof and get inside, they know what to do: shop. "It's Christmastime down there, buddy," both in the real world they have left behind and the refuge in which they now play. The empty J. C. Penney provides a television, a radio, lighter fluid, chocolate. They turn on the lights, the music, the fountains. A prerecorded announcement breaks into the Muzak: "Why pay more when the sales are popping here?" Why pay more indeed? In the zombie apocalypse, everything is free.

![]()

![]()

figs.i,ii

By the mid-1970s, the mall was enough of a fixture in American life to inspire a first round of reinterpretation. The festival marketplace and Jerde's themed environments elaborated on the standard-issue model by adding entertainment and city (or citylike) elements. Filmmakers such as Romero and writers from essayist Joan Didion to young adult author Richard Peck tried to make sense of the zoned-out (or blissed-out) feelings we have at the mall. Is this really living, or are we the undead? These artists were early to sense that all was not right in the land of consumption-1982 is considered the first "peak mall" year, the boom followed by the bust-but would not be the last. Every time malls grow unchecked, a die-off results and art is born from the entrails. Dawn of the Dead is cheap and cheesy and gross; New York Times film critic Janet Maslin lasted only fifteen minutes into the screening and filed her review from the theater lobby: "It was explained to me in the lobby, while a preview audience moaned and groaned, that... the bulk of Dawn of the Dead had been filmed in America's largest shopping mall and is full of satirical points about consuming." The movie would set the stage for decades of similarly scavenger-driven mall art.

![]()

![]()

Malls have been dying for the past forty years. Every decade rewrites the obituary in its own terms, but the apocalyptic scale, the language and imagery of civilizational collapse, keep reappearing. These narratives suggest an inevitability. And yet, the majority of malls survive. And yet, people keep shopping. The urban and suburban landscapes in which people live don't change that rapidly. Neither does human nature.

Joan Didion's essay "On the Mall," written in 1975 and anthologized in The White Album, is the second significant assessment of the mall as a cultural force after Ray Bradbury's The Girls Walk This Way: The Boys Walk That Way. While Bradbury situates himself as an observer, sitting on a bench, Didion walks with the girls. She spent time as a child at Town and Country Village outside Sacramento in the 1940s and, as a twentysomething working for Vogue in the 1960s, took a correspondence course on shopping center theory. "My dream life was to put together a Class-A regional shopping center with three full-line department stores as major tenants," she writes. She is disdainful of the knowledge she learned in the course but remains fascinated by the mall as an artifact, writing from the same bird's-eye vantage as Romero's helicopter crew.

![]()

![]()

fig.v,vi

They float on the landscape like pyramids to the boom years, all those Plazas and Malls and Esplanades. All those Squares and Fairs. All those Towns and Dales, all those Villages, all those Forests and Parks and Lands. Stonestown. Hillsdale. Valley Fair, Mayfair, Northgate, Southgate, Eastgate, Westgate. Gulfgate. They are toy garden cities in which no one lives but everyone consumes.

She recognizes, even embraces, the trancelike nature of mall shopping, taking herself to the open-air Ala Moana Center in Honolulu on a day in which she "wake[s] feeling low." (Opened in 1959, Ala Moana was for a time the largest mall in the United States.) In the soothing environs of its carp pools, she "moves for a while in aqueous suspension not only of light but of judgement, not only of judgement but of personality."" She goes in for a New York Times and comes out with two straw hats, four bottles of nail polish, and a toaster. The Gruen transfer has taken hold and, like Bradbury, she is fine with that. The absence of judgment in Didion's and Bradbury's essays may come from the place they shared: California, where any public life, even with a shopping tag attached, seems better than the car-dominated alternative.

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.vii-ix

Romero's take is far harsher. Standing at the railing on the second floor of the 1.1 million square foot Monroeville, Pennsylvania, mall, watching zombies jerk their way up the escalator and into the circular fountain, blond baby-faced SWAT team member Roger (Scott H. Reininger) asks his leader, Peter (Ken Force), "Why did they come here?" "This was an important place in their lives." Roger responds. Over the course of the film, Romero checks in with every architectural totem of the mall-the skating rink, the feature clock, the circular fountain, the planting beds, showing the audience that the familiar landmarks remain; in one memorable sequence, a zombie topples into the fountain.

But for all the characters' sneering commentary on the automatic behavior of the zombies, it is the healthy humans who seem unable to leave the mall. Rather than seeking supplies and fuel and heading north, they stay, stealing lamps and sofas to domesticate their hideaway, going on dates in the sit-down restaurant, and posing for the security cameras with stacks of bills.

The men can analyze but not resist the allure. Francine (Gaylen Ross), the one woman in the group, grows frustrated with her compatriots' complacency and gets angry. "You are hypnotized by this place, all of you! It's so bright and neatly wrapped, you don't see that it is a prison too."

![]()

![]()

Romero inserts visual jokes, cutting between the ashen faces of the zombies and the plastic tans of the mannequins. Eventually, as morale declines, Francine makes herself up to look like one of the mannequins, all blue eyeshadow, false lashes, and blood-red lipsticked mouth. The dialogue distances the sick from the well, but the visuals underline their sameness. To survive, they must escape the soft life at the mall. In the end Francine, pregnant and desperate, breaks the hypnosis. She and the one man left alive chopper toward Canada to start civilization anew: a clear Nativity reference, given the perpetual Christmas in the mall they leave behind.

Even as fin de siècle malls shuffled tenants, shut down wings, emptied out, limped on-the language of the undead permeates all the retail reportage they maintained cultural status through the art made by the children who grew up in their marble halls. The minute a mall shuts down, the documentation and the re-creation begins, in the work of Romero and Didion in the 1970s, John Hughes in the 1980s, mallwave composers and dystopian authors in the 2010s. For artistic creators and property developers alike, the dead mall is not the endgame, but rather the start of something new.

![]()

![]()

This question is asked and answered in George Romero's 1978 cult classic Dawn of the Dead, the second part of a planned horror trilogy. Four survivors of a zombie attack steal a TV helicopter and head north, making for Canada. As they chopper over fields and roads, they find that the virus has spread past the bounds of the city. Every open space includes dark figures that stagger toward some undefined goal. Low on fuel and sleep, the escapees reach a vast, empty parking lot. "What the hell is it?" someone asks, as if encountering the ruin of an ancient civilization. "Looks like a shopping center, one of those big indoor malls" is the reply.

Although the mall was unrecognizable from the air, once they land the helicopter on the roof and get inside, they know what to do: shop. "It's Christmastime down there, buddy," both in the real world they have left behind and the refuge in which they now play. The empty J. C. Penney provides a television, a radio, lighter fluid, chocolate. They turn on the lights, the music, the fountains. A prerecorded announcement breaks into the Muzak: "Why pay more when the sales are popping here?" Why pay more indeed? In the zombie apocalypse, everything is free.

figs.i,ii

By the mid-1970s, the mall was enough of a fixture in American life to inspire a first round of reinterpretation. The festival marketplace and Jerde's themed environments elaborated on the standard-issue model by adding entertainment and city (or citylike) elements. Filmmakers such as Romero and writers from essayist Joan Didion to young adult author Richard Peck tried to make sense of the zoned-out (or blissed-out) feelings we have at the mall. Is this really living, or are we the undead? These artists were early to sense that all was not right in the land of consumption-1982 is considered the first "peak mall" year, the boom followed by the bust-but would not be the last. Every time malls grow unchecked, a die-off results and art is born from the entrails. Dawn of the Dead is cheap and cheesy and gross; New York Times film critic Janet Maslin lasted only fifteen minutes into the screening and filed her review from the theater lobby: "It was explained to me in the lobby, while a preview audience moaned and groaned, that... the bulk of Dawn of the Dead had been filmed in America's largest shopping mall and is full of satirical points about consuming." The movie would set the stage for decades of similarly scavenger-driven mall art.

figs.iii,iv

Malls have been dying for the past forty years. Every decade rewrites the obituary in its own terms, but the apocalyptic scale, the language and imagery of civilizational collapse, keep reappearing. These narratives suggest an inevitability. And yet, the majority of malls survive. And yet, people keep shopping. The urban and suburban landscapes in which people live don't change that rapidly. Neither does human nature.

Joan Didion's essay "On the Mall," written in 1975 and anthologized in The White Album, is the second significant assessment of the mall as a cultural force after Ray Bradbury's The Girls Walk This Way: The Boys Walk That Way. While Bradbury situates himself as an observer, sitting on a bench, Didion walks with the girls. She spent time as a child at Town and Country Village outside Sacramento in the 1940s and, as a twentysomething working for Vogue in the 1960s, took a correspondence course on shopping center theory. "My dream life was to put together a Class-A regional shopping center with three full-line department stores as major tenants," she writes. She is disdainful of the knowledge she learned in the course but remains fascinated by the mall as an artifact, writing from the same bird's-eye vantage as Romero's helicopter crew.

fig.v,vi

They float on the landscape like pyramids to the boom years, all those Plazas and Malls and Esplanades. All those Squares and Fairs. All those Towns and Dales, all those Villages, all those Forests and Parks and Lands. Stonestown. Hillsdale. Valley Fair, Mayfair, Northgate, Southgate, Eastgate, Westgate. Gulfgate. They are toy garden cities in which no one lives but everyone consumes.

She recognizes, even embraces, the trancelike nature of mall shopping, taking herself to the open-air Ala Moana Center in Honolulu on a day in which she "wake[s] feeling low." (Opened in 1959, Ala Moana was for a time the largest mall in the United States.) In the soothing environs of its carp pools, she "moves for a while in aqueous suspension not only of light but of judgement, not only of judgement but of personality."" She goes in for a New York Times and comes out with two straw hats, four bottles of nail polish, and a toaster. The Gruen transfer has taken hold and, like Bradbury, she is fine with that. The absence of judgment in Didion's and Bradbury's essays may come from the place they shared: California, where any public life, even with a shopping tag attached, seems better than the car-dominated alternative.

figs.vii-ix

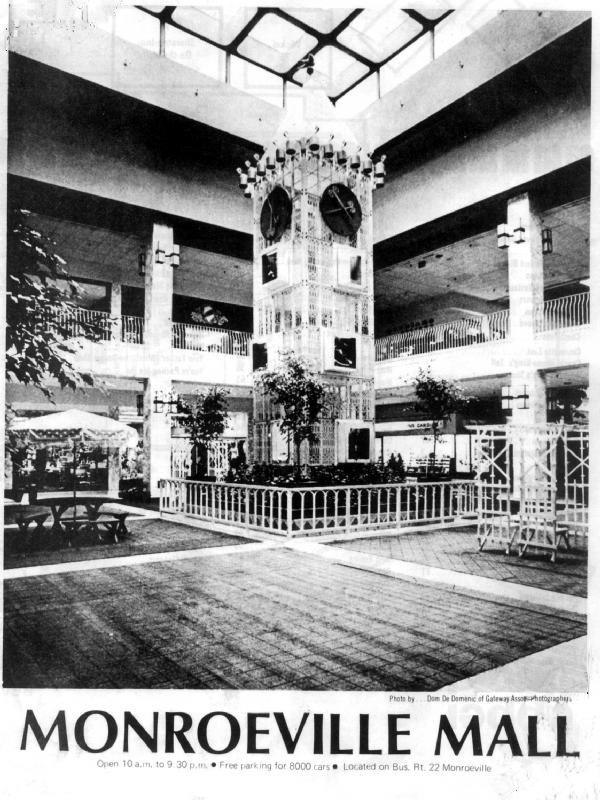

Romero's take is far harsher. Standing at the railing on the second floor of the 1.1 million square foot Monroeville, Pennsylvania, mall, watching zombies jerk their way up the escalator and into the circular fountain, blond baby-faced SWAT team member Roger (Scott H. Reininger) asks his leader, Peter (Ken Force), "Why did they come here?" "This was an important place in their lives." Roger responds. Over the course of the film, Romero checks in with every architectural totem of the mall-the skating rink, the feature clock, the circular fountain, the planting beds, showing the audience that the familiar landmarks remain; in one memorable sequence, a zombie topples into the fountain.

But for all the characters' sneering commentary on the automatic behavior of the zombies, it is the healthy humans who seem unable to leave the mall. Rather than seeking supplies and fuel and heading north, they stay, stealing lamps and sofas to domesticate their hideaway, going on dates in the sit-down restaurant, and posing for the security cameras with stacks of bills.

The men can analyze but not resist the allure. Francine (Gaylen Ross), the one woman in the group, grows frustrated with her compatriots' complacency and gets angry. "You are hypnotized by this place, all of you! It's so bright and neatly wrapped, you don't see that it is a prison too."

figs.x,xi

Romero inserts visual jokes, cutting between the ashen faces of the zombies and the plastic tans of the mannequins. Eventually, as morale declines, Francine makes herself up to look like one of the mannequins, all blue eyeshadow, false lashes, and blood-red lipsticked mouth. The dialogue distances the sick from the well, but the visuals underline their sameness. To survive, they must escape the soft life at the mall. In the end Francine, pregnant and desperate, breaks the hypnosis. She and the one man left alive chopper toward Canada to start civilization anew: a clear Nativity reference, given the perpetual Christmas in the mall they leave behind.

Even as fin de siècle malls shuffled tenants, shut down wings, emptied out, limped on-the language of the undead permeates all the retail reportage they maintained cultural status through the art made by the children who grew up in their marble halls. The minute a mall shuts down, the documentation and the re-creation begins, in the work of Romero and Didion in the 1970s, John Hughes in the 1980s, mallwave composers and dystopian authors in the 2010s. For artistic creators and property developers alike, the dead mall is not the endgame, but rather the start of something new.

figs.xii,xiii

Alexandra Lange is a design critic and the author of four previous books, including The Design of Childhood. Her writing has also appeared in publi cations such as the New Yorker, the Atlantic, New York Magazine, and the New York Times, and she has been a featured writer at Design Observer, an opinion columnist at Dezeen, and the architecture critic for Curbed. She holds a PhD in twentieth-century architecture history from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. She lives in Brooklyn.

www.alexandralange.net

buy

You can buy

Meet Me By The Fountain: An Inside History Of The Mall

at bookshops widely or online. Further information available from the Bloomsbury website

www.bloomsbury.com/us/meet-me-by-the-fountain-9781635576023

images

fig.i Still image from Dawn of the Dead, dir. George Romero (1978)

fig.ii The Monroeville Mall, location for Dawn of the Dead, in 2001.

© Brett McBean. Available at: www.brettmcbean.com/horror-trippin-2/dawn-of-the-dead

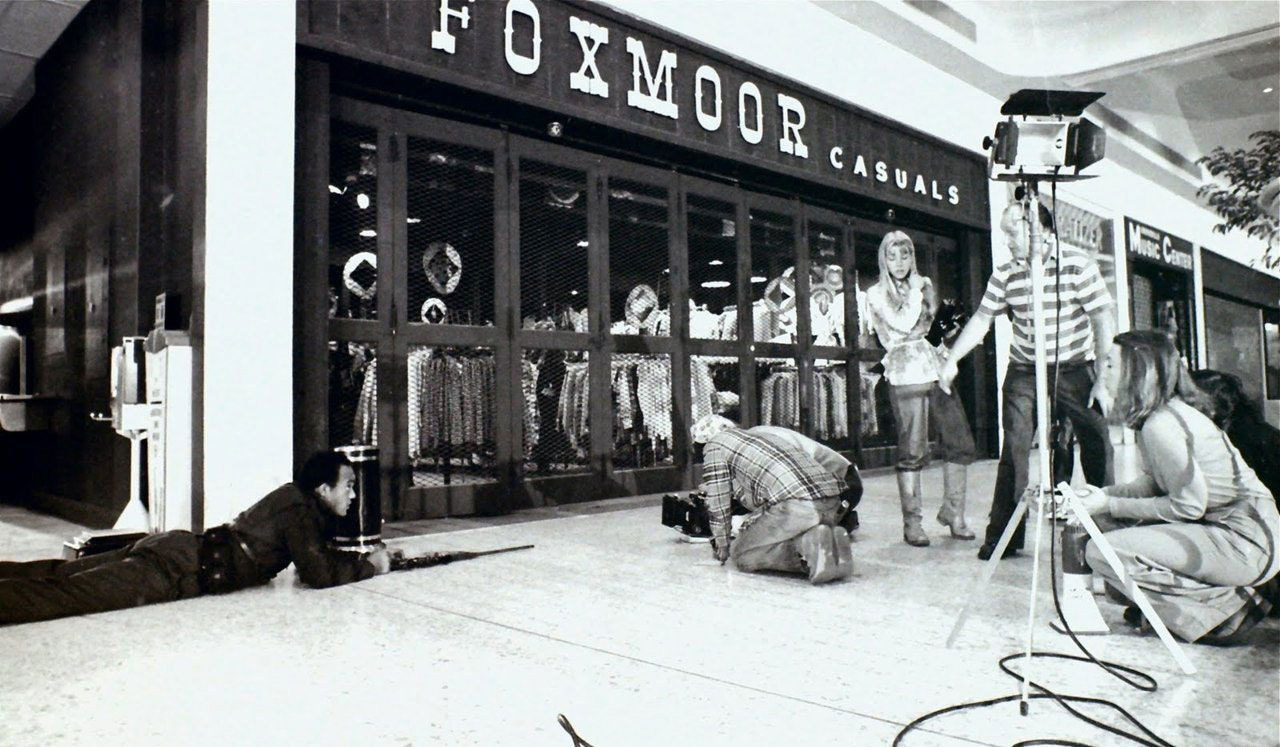

fig.iii Filming of Dawn of the Dead

, dir. George Romero (1978)

fig.iv Owings Mills Mall outside Baltimore,

designed by RTKL Associates Inc. in 1986, was cannibalized by a bigger, newer

mall and demolished in 2016.

©

Abandoned America/Matthew Christopher. Courtesy Bloomsbury Publishing.

fig.v

“Every day will be a perfect shopping day”

at Southdale, opened in 1956, and considered the first enclosed shopping center

in the United States. The central atrium was named the Garden Court of

Perpetual Spring and featured an aviary.

©

Gruen Associates. Courtesy Bloomsbury Publishing.

fig.vi Aerial view of the Mall of America, Bloomington, Minnesota. Courtesy Bloomsbury Publishing.

figs.vii-ix Archive brochure for Monroeville Mall (unknown date).

figs.x,xi

Still images from Dawn of the Dead, dir. George Romero (1978)

fig.xii Cover of Meet Me By The Fountain: An Inside History Of The Mall (2022), by Alexandra Lange, published by Bloomsbury Publishing.

fig.xiii

Filming of Dawn of the Dead, dir. George Romero (1978)

publication date

03 July 2022

tags

Ray Bradbury, Dawn of the Dead, Joan Didion, Film, Horror, Andrea Lange, Mall, Meet me by the fountain, George Romero, Shopping centre, Shopping mall, Suburbs, Zombies

www.bloomsbury.com/us/meet-me-by-the-fountain-9781635576023