Grave

Rubber: An Interview with Scott Covert

The

aura of lives passed are brought into life and into the gallery with Scott

Covert’s work, formed of overlapping, montaged graveyard rubbings. Robert Barry

visited London’s Studio Voltaire to speak to the artist, delving beneath the

canvas to discover the intermingling memories within.

Scott

Covert already has his own burial ground all planned out. “I have a really good grave,” he tells me, as we

amble round his show at London’s Studio Voltaire gallery, pointing out famous

names and cackling over past hijinks. “I have a plot in Michigan – where the

Covert family is. It’s a gorgeous old cemetery. There’s one last spot and the

family said I can have it.”

It’s unsurprising, perhaps, that he might already have considered the site of his final resting place. Over the past three and a half decades, Covert has become something of a churchyard connoisseur. “This has become my life,” he says, gesturing around the room at the dozens of works on paper and canvas, each one built upon rubbings taken from the surface of a tombstone – many of them celebrities. “I don’t do anything else,” he tells me. “I mean anything. I like being by myself.” It may sound like a morbid pursuit, but Covert sees things differently: “it’s really not about death,” he insists. “It’s about life.”

![]()

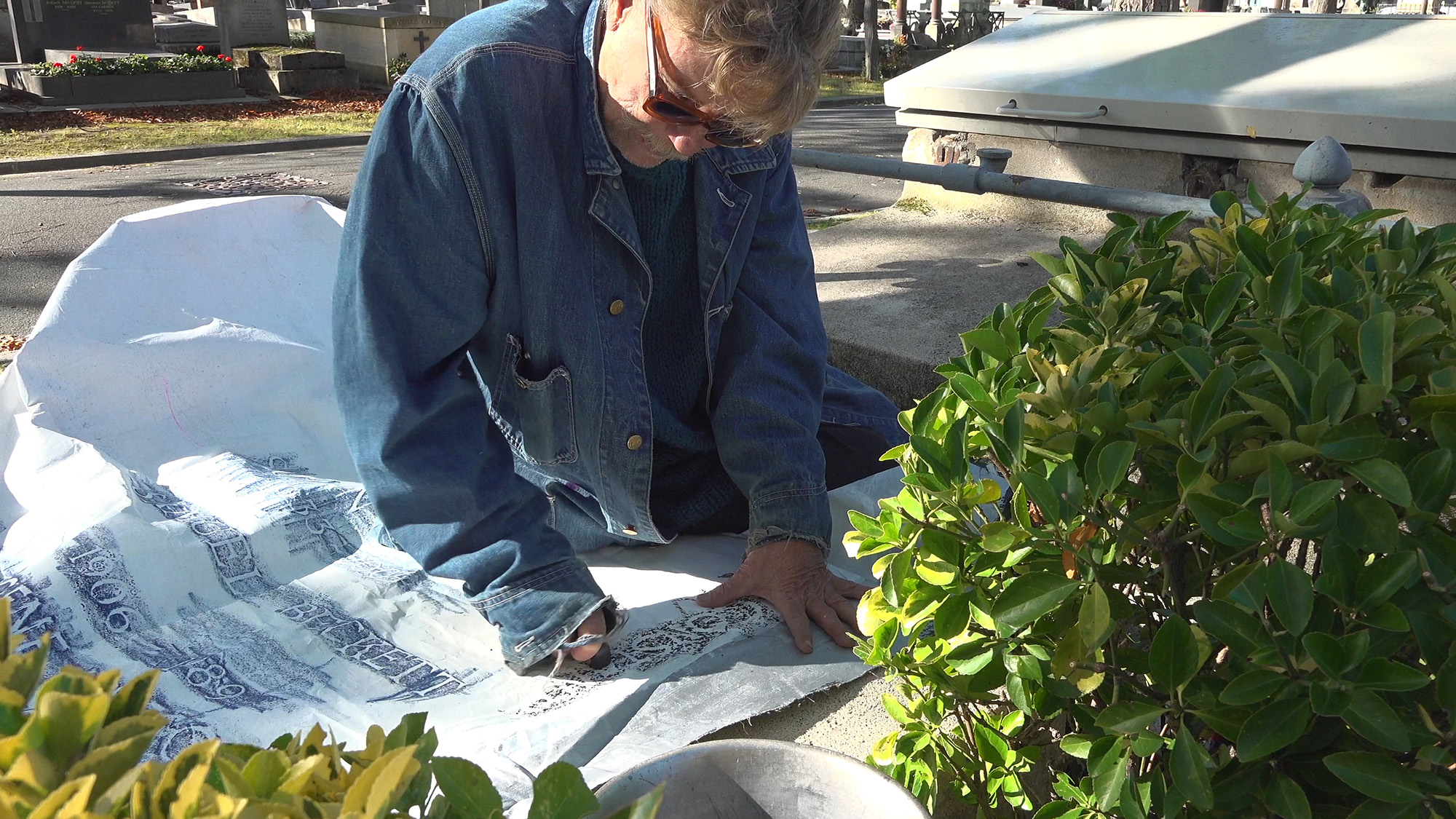

The process is called frottage (and the word, with its air of innuendo, clearly delights Covert). You place a sheet against an uneven surface and with chalk, oil stick, or charcoal lightly rub to take a rendering of its projections and indentations. In the 1920s, Max Ernst created surrealist landscapes by placing pieces of paper over the lines of a worn wooden floor and carefully working over in a frenzied back and forth until the texture came through. Later, from the 1950s, art school dropout turned military cartographer, Michelle Stuart took rubbings on rag paper from cave walls near San Juan Ermita de Chiquimula in Guatemala.

Stuart was a mapmaker, formerly of the United States Army Corps of Engineers in the Korean War; so, in a sense, is Covert. His works trace the texture of the land and its monuments, sounding reliefs and topographies, drawing imaginary lines between distant points. And Covert has favourite cemeteries (especially Woodlawn in New York) and particular graves that he returns to often, lugging sacks full of canvases everywhere he goes, each encounter producing a new, unique record of a perfectly singular event. None of his works are based on templates or copies; each one is a direct footprint, a position in time and space. They record the quixotic movements of a life that has become almost permanently itinerant.

![]()

Grave rubbing had been popular in the Victorian era. Initially a hobbyist pursuit, stemming from the rising bourgeoisie’s newfound interest in heredity, it registered the changing class structure of Europe’s long nineteenth century. Covert’s work equally registers its own point of origin in mid-80s New York, with its new aristocracy of movie stars and disco singers, ravaged by an AIDS crisis that was turning the city itself into a mausoleum. Many of the names that adorn these walls are old friends of Covert’s or former neighbours from his days as an adolescent runaway living in the Chelsea Hotel, people like Warhol superstar Jackie Curtis, or Nancy Spungen, tragic partner of Sid Vicious.

It started in 1985 with a trip to the grave of Florence Ballard at Detroit Memorial Park Cemetery in Warren, Michigan. What brought you there? I ask Covert. “To go to Flo’s grave,” he says simply. The daughter of a General Motors employee, Ballard had founded The Supremes (originally called The Primettes) in 1960, while still in high school. Her expulsion from the group precipitated a spiral of alcoholism and depression. She died from a heart attack in 1976, only 32 years of age. Since then, her name has become something of a byword for that potent cocktail of glamour mixed with tragedy. “I did a rubbing,” Covert continues. “And when I did a rubbing, it moved. So I used another colour. And then I thought, oh! And I just kept on doing like this. And then I thought, I’m making an abstract painting!”

As an origin story, it’s telling. Only when the paper slips, occluding the signifying power of the embossed letters and veering towards abstraction, does Covert suddenly recognise what he’s doing as a kind of artistic activity. In some of his works, names pile up in dense clumps, different colours, different angles, textures, patterns. And yet there is an odd sort of stickiness to the denotative force of words and names.

![]()

It was not just any grave that brought Covert to Michigan. It had to be Flo. In some works, there is a hint of narrative: Donna Summer is reunited with Sylvester, disco’s queen and king; Factory regulars Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling, and Edie Sedgwick clump together on another canvas; Khrushchev criss-crosses with Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Edgar Allen Poe is placed beside Mies van der Rohe simply because Covert enjoyed the rhyme: “I amuse myself as I’m doing it,” he shrugs.

But many of the celebrities whose undead autograph Covert has collected belong to another era, the time of his own 1950s and 60s childhood. We see the likes of Charles Laughton and Humphrey Bogart, John Dillinger, and Rudolph Valentino. There’s nostalgia there – and a hint of melancholy, too, since every act of grave rubbing will subtly abrade the grave being rubbed. The work simultaneously commemorates and erodes its object. It is marked by loss.

![]()

Covert’s work evokes the mid-century in another way, too: acting almost as a telescoping of all the major art movements of the period, with the colour fields and nutty textures of Rothko or Tàpies, the wordplay of Kossuth and Weiner, and a sensibility that feels utterly Pop. These are rich, vivid works, dense with allusion, still highly playful. On each canvas, history collapses into reverie. Times explodes into space. With its sticky beak for violent tragedy and its cold, twisted ironies, Covert’s work could be the twentieth century in nuce.

It’s unsurprising, perhaps, that he might already have considered the site of his final resting place. Over the past three and a half decades, Covert has become something of a churchyard connoisseur. “This has become my life,” he says, gesturing around the room at the dozens of works on paper and canvas, each one built upon rubbings taken from the surface of a tombstone – many of them celebrities. “I don’t do anything else,” he tells me. “I mean anything. I like being by myself.” It may sound like a morbid pursuit, but Covert sees things differently: “it’s really not about death,” he insists. “It’s about life.”

The process is called frottage (and the word, with its air of innuendo, clearly delights Covert). You place a sheet against an uneven surface and with chalk, oil stick, or charcoal lightly rub to take a rendering of its projections and indentations. In the 1920s, Max Ernst created surrealist landscapes by placing pieces of paper over the lines of a worn wooden floor and carefully working over in a frenzied back and forth until the texture came through. Later, from the 1950s, art school dropout turned military cartographer, Michelle Stuart took rubbings on rag paper from cave walls near San Juan Ermita de Chiquimula in Guatemala.

Stuart was a mapmaker, formerly of the United States Army Corps of Engineers in the Korean War; so, in a sense, is Covert. His works trace the texture of the land and its monuments, sounding reliefs and topographies, drawing imaginary lines between distant points. And Covert has favourite cemeteries (especially Woodlawn in New York) and particular graves that he returns to often, lugging sacks full of canvases everywhere he goes, each encounter producing a new, unique record of a perfectly singular event. None of his works are based on templates or copies; each one is a direct footprint, a position in time and space. They record the quixotic movements of a life that has become almost permanently itinerant.

Grave rubbing had been popular in the Victorian era. Initially a hobbyist pursuit, stemming from the rising bourgeoisie’s newfound interest in heredity, it registered the changing class structure of Europe’s long nineteenth century. Covert’s work equally registers its own point of origin in mid-80s New York, with its new aristocracy of movie stars and disco singers, ravaged by an AIDS crisis that was turning the city itself into a mausoleum. Many of the names that adorn these walls are old friends of Covert’s or former neighbours from his days as an adolescent runaway living in the Chelsea Hotel, people like Warhol superstar Jackie Curtis, or Nancy Spungen, tragic partner of Sid Vicious.

It started in 1985 with a trip to the grave of Florence Ballard at Detroit Memorial Park Cemetery in Warren, Michigan. What brought you there? I ask Covert. “To go to Flo’s grave,” he says simply. The daughter of a General Motors employee, Ballard had founded The Supremes (originally called The Primettes) in 1960, while still in high school. Her expulsion from the group precipitated a spiral of alcoholism and depression. She died from a heart attack in 1976, only 32 years of age. Since then, her name has become something of a byword for that potent cocktail of glamour mixed with tragedy. “I did a rubbing,” Covert continues. “And when I did a rubbing, it moved. So I used another colour. And then I thought, oh! And I just kept on doing like this. And then I thought, I’m making an abstract painting!”

As an origin story, it’s telling. Only when the paper slips, occluding the signifying power of the embossed letters and veering towards abstraction, does Covert suddenly recognise what he’s doing as a kind of artistic activity. In some of his works, names pile up in dense clumps, different colours, different angles, textures, patterns. And yet there is an odd sort of stickiness to the denotative force of words and names.

It was not just any grave that brought Covert to Michigan. It had to be Flo. In some works, there is a hint of narrative: Donna Summer is reunited with Sylvester, disco’s queen and king; Factory regulars Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling, and Edie Sedgwick clump together on another canvas; Khrushchev criss-crosses with Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Edgar Allen Poe is placed beside Mies van der Rohe simply because Covert enjoyed the rhyme: “I amuse myself as I’m doing it,” he shrugs.

But many of the celebrities whose undead autograph Covert has collected belong to another era, the time of his own 1950s and 60s childhood. We see the likes of Charles Laughton and Humphrey Bogart, John Dillinger, and Rudolph Valentino. There’s nostalgia there – and a hint of melancholy, too, since every act of grave rubbing will subtly abrade the grave being rubbed. The work simultaneously commemorates and erodes its object. It is marked by loss.

Covert’s work evokes the mid-century in another way, too: acting almost as a telescoping of all the major art movements of the period, with the colour fields and nutty textures of Rothko or Tàpies, the wordplay of Kossuth and Weiner, and a sensibility that feels utterly Pop. These are rich, vivid works, dense with allusion, still highly playful. On each canvas, history collapses into reverie. Times explodes into space. With its sticky beak for violent tragedy and its cold, twisted ironies, Covert’s work could be the twentieth century in nuce.

Scott

Covert (b. New Jersey, 1954), based in New York, was previously a collaborator

with Off-Broadway theatre companies in the late ’70s and was a founding member

of Playhouse 57 at the storied Club 57 in the East Village. Throughout this

formative period, Covert was immersed in New York’s downtown nightlife and

cultural milieu, where his friends and contemporaries included writer and

actress Cookie Mueller, as well as poet and artist Rene Ricard, who both

encouraged him to develop his artistic practice. In 2017 his solo exhibition,

The Dead Supreme, was on view simultaneously at Situations and Fierman Gallery,

both New York, and his work has been exhibited at Mark Moore Gallery, Santa

Monica, CA; Makeshift Gallery, Provincetown, MA; Finesilver Gallery, San

Antonio, TX; The Fun Gallery New York, NY; and in Found Objects, curated by

Keith Haring at Club 57 New York, NY. His work featured prominently in Club 57:

Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978-1983 at MoMA, New York

(2018), the first major exhibition to fully examine the scene-changing,

interdisciplinary life of this seminal downtown New York alternative space. A

major survey exhibition of his work is forthcoming at NSU Art Museum Fort

Lauderdale in 2022.

Robert Barry is a freelance writer and musician based in London. His most recent book, Compact Disc, was published by Bloomsbury in 2020.

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

visit

C’est la vie, by Scott

Covert, is exhibiting at Studio Voltaire until 26 March. Full details available

from the gallery’s website at:

www.studiovoltaire.org/whats-on/scott-covert-2023

images

installation views Scott Covert, C’est la vie, Installation Views, Studio Voltaire, 2023, Images courtesy of the artist and Studio Voltaire, Photography

©

Sarah Rainer

rubbing image Scott Covert, Up Until Now (still),

c.1990–2022

Video (colour, sound)

22 minutes and 21 seconds. Filming by Lex Niarchos, Editing

by Jin Lee

publication date

13 February 2022

tags

AIDs,

Florence Ballard, Robert Barry, Scott Covert, Jackie Curtis, Death, Detroit

Memorial Park Cemetery, Max Ernst, Frottage, Grave, Graveyard, Headstone, Life,

Rubbing, Nancy Spungen, Michelle Stuart, Studio Voltaire, The Supremes, Tombstone,

Rudolph Valentino

www.studiovoltaire.org/whats-on/scott-covert-2023