Building culture in Camden: Reed Watts’ Roundhouse extension

Camden’s celebrated arts venue Roundhouse has recently seen an

extension to both its architecture and community offer. Robert Barry visits

Roundhouse Works, a

workspace & development programme opening for creative industry freelancers

aged 18-30, designed by architects Reed Watts to see what it brings to the area.

There are Byzantine churches built from the ruins of the pagan

temples they replaced. Look closely at the outer walls of the eleventh-century

Holy Church of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary in Kalambaka, central Greece.

Amongst the bricks, you’ll spot fragments of the ancient Greek place of worship

that once stood on the same site – the base of a Doric column, the domed head

of a statue – incorporated into the stonework. Roundhouse Works, a new space

for young creative freelancers in Camden squatting down by the side of the

legendary rail shed-turned-music venue, takes a similarly magpie-like approach

to its materials.

![]()

![]()

Figs.i,ii

Poking up behind the yellow-brick Victorian retaining wall that runs along Chalk Farm Road, the building’s street-facing façade is clad in reclaimed wooden railway sleepers, a nod to the site’s former role in the North London Railway. Seen up close, each plank reveals its own distinctive patina, some darker or lighter in colour, rougher or smoother in texture. In some, there are boltholes, no longer bolted – “I think bees are going to like them,” Matt Watts of architects Reed Watts suggests. And across a few planks, scattered here and there, faint spray-painted markings: “H4” in an electric blue scrawl, a line of dashed of yellow “X”s, inscrutable fragments of some bygone code known only to rail track infrastructure engineers.

These wooden planks, shaved to barely an inch-thick, provide the greater part of Roundhouse Works’ exterior character – its public face, as it were. That’s what you see when you walk down the street and that’s what the publicity photos in the press predominantly show. The metallic lettering fixed onto the Regents Park Road side announce in a bold Sans-serif the building’s intentions: “Creative Studios and Work Space for Young People.”

![]()

![]()

Figs.iii,iv

This particular street corner was always the fag-end of Camden Town, a little nowhere on the way to the tube before the streets peels off towards more the salubrious zones of Belsize Park and Primrose Hill. As Roundhouse Works lead architect Paddy Dillon puts it, it was all “very grim.” The Roundhouse’s outdoor bar, service yard, back offices and occasional beach would hide behind a pair of giant advertising hoardings and a dark wraparound timber fence, as if slightly embarrassed by the association.

Today, that’s all gone. The fence has come down, so from the street you can see up onto the courtyard between the old Roundhouse building and the new Roundhouse Works and glean some sense of life and activity going on there. Youthful creatives on the inside might also look up from their work and out of the windows cut into those railway sleepers and see a street scene somewhat smartened up – but notably less abundant in precisely the kind of cultural activities they are supposed to be eagerly producing.

The Marathon Bar kebab shop, where the Kingsnakes’ Daniel Jeanrenaud used to play Hippy Hippy Shake into the wee hours, once a reliable post-gig drinking and dancing den patronised by Amy Winehouse and Jack White, long ago lost its late license. It now pretty much just sells kebabs. The Barfly, former central node in the 00s indie scene, has been revamped as a vegetarian restaurant. The Enterprise hasn’t put on a gig in nearly a decade (but it does now have a brunch menu).

![]()

![]()

Figs.v,vi

“It’s incredibly challenging for the arts in Britain now,” Dillon says when we pop inside to chat. Despite its very civic-sounding mission to give young people a leg up in the creative industries, Roundhouse Works was built without a penny of public money. Local MP Keir Starmer pops up in the project press release, touting the place as “a great example of the level of ambition we need across the country to equip the next generation with the skills and support they need to succeed in the arts.” But as Leader of the Opposition, Starmer has pledged little in the way of reversing a decade of Tory cuts to the arts and arts education.

They make for an odd couple, Dillon and Watts, as they show me round the place. The former, with his open-necked shirt and endearingly mole-ish features, looks every bit what you expect an architect to look like; while the latter, in a ponytail, t-shirt, and roll-top waterproof rucksack, might be mistaken for some sort of digital nomad or perhaps the guy who finally quit his band to teach history at a local comprehensive where he will be mercilessly eaten alive by the pupils. But they exhibit a refreshing openness, emphasising the years of ruminative dialogue that preceded any thought of building here and the hardwired flexibility of all the resulting spaces.

![]()

![]()

Figs.vii,viii

Every built element of the space seems to function in multiple ways, offering the potential for this or the possibility for that. “The aim,” as Dillon tells me, “was to make lots of different places in which people could work in very different ways.” But when I looked around on an early afternoon one Tuesday in mid-September, the building was mostly empty, aside from a small handful buried in their laptops in the main first floor co-working space – though Roundhouse’s head of comms, Tor Evans, assures me that, after just three months open, they already have 50 or 60 members running a diverse range of cultural businesses there.

In order to get more of a sense of how the place actually is used, I sat down with one of those members, a freelance audio producer named Marnie. “I did a traineeship before Roundhouse Works in the young people’s studio,” she says, referring to the basement home of the Roundhouse Trust underneath the Roundhouse itself. The studios there are for 18 to 25 year-olds, while the new building extends that range up to 30, so when Marnie was “cruelly aged out” of the other place, she applied to join Roundhouse Works. For her, the main bonus of working here rather than in her own home comes down to “having a community around you,” whether that means joining workshops, finding new collaborators or simply “having a chat with someone while you get a cup of tea.”

Like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, there’s a sense here that the building has been designed to facilitate people bumping into each other and sparking up spontaneous conversations. “The whole space is built on that ethos of not just being given a space but being given a network of people,” Marnie says. “I haven’t used the triple-height circus space yet,” she tells me, gesturing to the wood-lined big-top-sized room above us. “But it’s really nice to know it’s there.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figs.ix-xii

Figs.i,ii

Poking up behind the yellow-brick Victorian retaining wall that runs along Chalk Farm Road, the building’s street-facing façade is clad in reclaimed wooden railway sleepers, a nod to the site’s former role in the North London Railway. Seen up close, each plank reveals its own distinctive patina, some darker or lighter in colour, rougher or smoother in texture. In some, there are boltholes, no longer bolted – “I think bees are going to like them,” Matt Watts of architects Reed Watts suggests. And across a few planks, scattered here and there, faint spray-painted markings: “H4” in an electric blue scrawl, a line of dashed of yellow “X”s, inscrutable fragments of some bygone code known only to rail track infrastructure engineers.

These wooden planks, shaved to barely an inch-thick, provide the greater part of Roundhouse Works’ exterior character – its public face, as it were. That’s what you see when you walk down the street and that’s what the publicity photos in the press predominantly show. The metallic lettering fixed onto the Regents Park Road side announce in a bold Sans-serif the building’s intentions: “Creative Studios and Work Space for Young People.”

Figs.iii,iv

This particular street corner was always the fag-end of Camden Town, a little nowhere on the way to the tube before the streets peels off towards more the salubrious zones of Belsize Park and Primrose Hill. As Roundhouse Works lead architect Paddy Dillon puts it, it was all “very grim.” The Roundhouse’s outdoor bar, service yard, back offices and occasional beach would hide behind a pair of giant advertising hoardings and a dark wraparound timber fence, as if slightly embarrassed by the association.

Today, that’s all gone. The fence has come down, so from the street you can see up onto the courtyard between the old Roundhouse building and the new Roundhouse Works and glean some sense of life and activity going on there. Youthful creatives on the inside might also look up from their work and out of the windows cut into those railway sleepers and see a street scene somewhat smartened up – but notably less abundant in precisely the kind of cultural activities they are supposed to be eagerly producing.

The Marathon Bar kebab shop, where the Kingsnakes’ Daniel Jeanrenaud used to play Hippy Hippy Shake into the wee hours, once a reliable post-gig drinking and dancing den patronised by Amy Winehouse and Jack White, long ago lost its late license. It now pretty much just sells kebabs. The Barfly, former central node in the 00s indie scene, has been revamped as a vegetarian restaurant. The Enterprise hasn’t put on a gig in nearly a decade (but it does now have a brunch menu).

Figs.v,vi

“It’s incredibly challenging for the arts in Britain now,” Dillon says when we pop inside to chat. Despite its very civic-sounding mission to give young people a leg up in the creative industries, Roundhouse Works was built without a penny of public money. Local MP Keir Starmer pops up in the project press release, touting the place as “a great example of the level of ambition we need across the country to equip the next generation with the skills and support they need to succeed in the arts.” But as Leader of the Opposition, Starmer has pledged little in the way of reversing a decade of Tory cuts to the arts and arts education.

They make for an odd couple, Dillon and Watts, as they show me round the place. The former, with his open-necked shirt and endearingly mole-ish features, looks every bit what you expect an architect to look like; while the latter, in a ponytail, t-shirt, and roll-top waterproof rucksack, might be mistaken for some sort of digital nomad or perhaps the guy who finally quit his band to teach history at a local comprehensive where he will be mercilessly eaten alive by the pupils. But they exhibit a refreshing openness, emphasising the years of ruminative dialogue that preceded any thought of building here and the hardwired flexibility of all the resulting spaces.

Figs.vii,viii

Every built element of the space seems to function in multiple ways, offering the potential for this or the possibility for that. “The aim,” as Dillon tells me, “was to make lots of different places in which people could work in very different ways.” But when I looked around on an early afternoon one Tuesday in mid-September, the building was mostly empty, aside from a small handful buried in their laptops in the main first floor co-working space – though Roundhouse’s head of comms, Tor Evans, assures me that, after just three months open, they already have 50 or 60 members running a diverse range of cultural businesses there.

In order to get more of a sense of how the place actually is used, I sat down with one of those members, a freelance audio producer named Marnie. “I did a traineeship before Roundhouse Works in the young people’s studio,” she says, referring to the basement home of the Roundhouse Trust underneath the Roundhouse itself. The studios there are for 18 to 25 year-olds, while the new building extends that range up to 30, so when Marnie was “cruelly aged out” of the other place, she applied to join Roundhouse Works. For her, the main bonus of working here rather than in her own home comes down to “having a community around you,” whether that means joining workshops, finding new collaborators or simply “having a chat with someone while you get a cup of tea.”

Like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, there’s a sense here that the building has been designed to facilitate people bumping into each other and sparking up spontaneous conversations. “The whole space is built on that ethos of not just being given a space but being given a network of people,” Marnie says. “I haven’t used the triple-height circus space yet,” she tells me, gesturing to the wood-lined big-top-sized room above us. “But it’s really nice to know it’s there.”

Figs.ix-xii

Reed Watts are an architectural

practice founded by Jim Reed and Matt Watts in 2016, formerly Associate

Directors at Haworth Tompkins. Based in Clerkenwell, the practice has a diverse

workload across culture and housing sectors. They have recently received a

Civic Trust award for their new pavilion for Teddington Cricket Club in Bushy

Park and have completed projects at the Open Air Theatre in Regent’s Park and

at the V&A Museum. They are currently working on projects for the

Roundhouse in Camden, a rough sleeper assessment centre for the City of London

and a number of Community Land Trusts in South-West England. Future projects

include a new community pavilion in Ashtead Park, a visitor centre for the

National Trust and retro-fit projects in Kingston-upon-Thames, Tufnell Park and

Tolworth.

www.reedwatts.com

Roundhouse is

an iconic music and arts venue in Camden. Since the Roundhouse reopened in

2006, we’ve opened up space for creativity to empower people and communities –

day in, night out. We’re on a mission to raise the creative potential of the UK

so we give young people and artists the space to experiment, develop skills and

be part of incredible moments that go down in history.

We host

world-famous musicians, iconic events and we create and curate our own shows

too, in a pioneering programme of live music, theatre, spoken word and circus.

This includes our flagship arts festivals, Roundhouse Rising, The Last Word and

In The Round.

Alongside live

events, harnessing the creativity of young people and new artists is built into

our DNA. Through our ambitious youth programme, 11-30 year-olds can take part

in creative opportunities or use affordable studio space that can ignite a

passion, develop skills or help them turn their creativity into a career. We

also nurture freelancers and entrepreneurs that are changing the future of the

creative industries.

www.roundhouse.org.uk

Robert Barry is a freelance writer and musician based in London. His most recent book, Compact Disc, was published by Bloomsbury in 2020.

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

We host world-famous musicians, iconic events and we create and curate our own shows too, in a pioneering programme of live music, theatre, spoken word and circus. This includes our flagship arts festivals, Roundhouse Rising, The Last Word and In The Round.

Alongside live events, harnessing the creativity of young people and new artists is built into our DNA. Through our ambitious youth programme, 11-30 year-olds can take part in creative opportunities or use affordable studio space that can ignite a passion, develop skills or help them turn their creativity into a career. We also nurture freelancers and entrepreneurs that are changing the future of the creative industries.

www.roundhouse.org.uk

Robert Barry is a freelance writer and musician based in London. His most recent book, Compact Disc, was published by Bloomsbury in 2020.

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

more information

More information on Roundhouse Young Creative Memberships for 13-25 year olds, and membership of Roundhouse Works for 18-30 year old, can be found on Roundhouse’s website alongside details of courses and events:

www.roundhouse.org.uk/young-creatives-11-30

images

figs.i-iv,vi,vii Roundhouse Works Reed Watts. Photographs © Fred Howarth.

figs.v,viii Roundhouse Works Inflexion Workspace. Photographs

©

Patrick Dempsey.

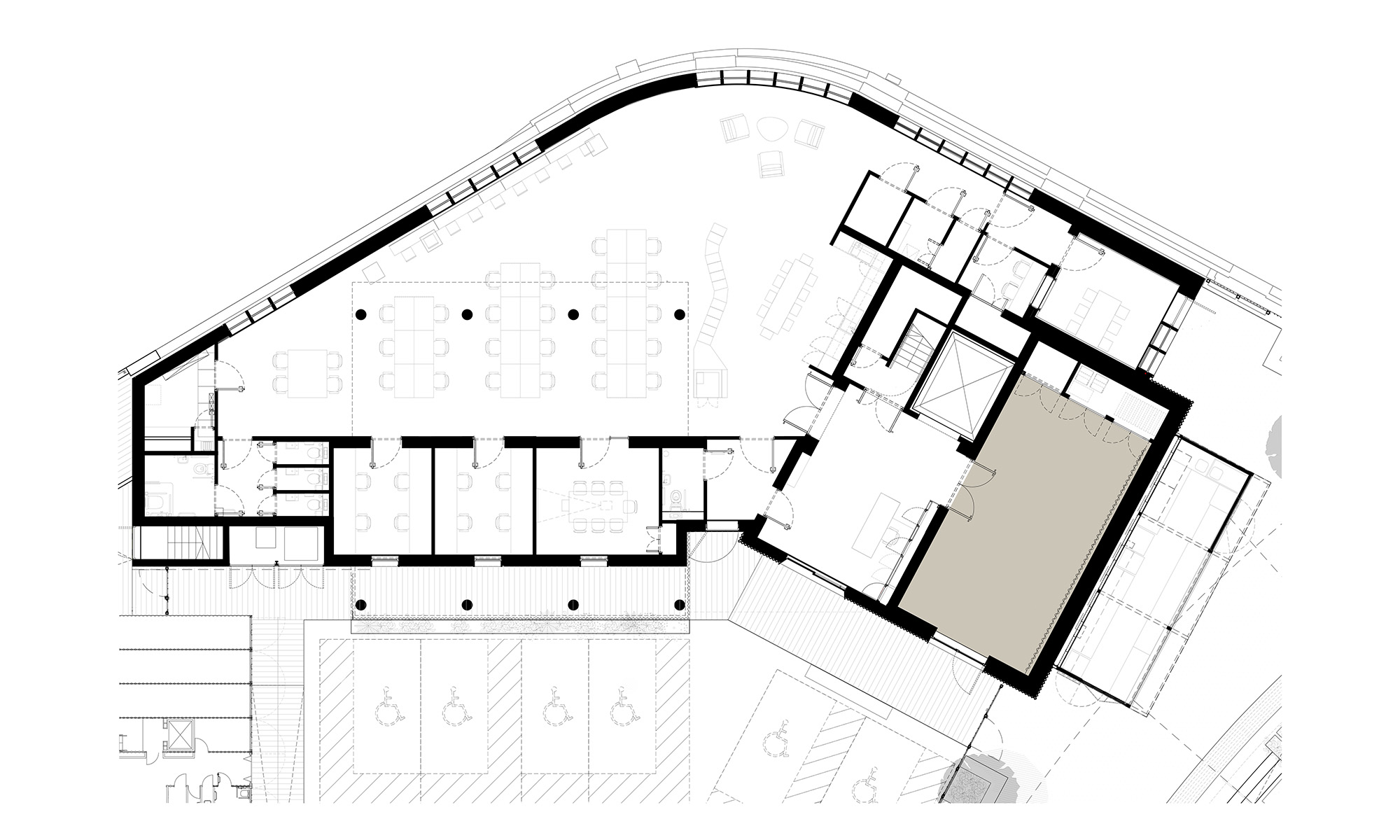

fig.ix-xii

Roundhouse Works floor plans & rendered sections. Drawings © Reed Watts.

publication date

25 September 2023

tags

The Barfly, Robert Barry, Camden, Circus, Community, Cultural sector, Paddy Dillon, The Enterprise, Tor Evans, Freelancers, London, The Marathon Bar, Marnie, Materials, Network, Railway, Reed Watts, Roundhouse, Keir Starmer, Matt Watts, Roundhouse Works, Wood

www.roundhouse.org.uk/young-creatives-11-30