Foto Industria: playing a photographic game across Bologna

The Foto Industria biennial explores photography’s

relationship to industry and work, across all creative approaches to the medium

from photojournalism to fine art, found imagery to digital creations. The theme

of this edition is the game industry in photography, with a selection of

international artists presented over exhibitions held at Fondazione MAST and across

other venues around the Italian city of Bologna. Nyima Murry visited, pulling

focus on the works of Andreas Gursky, Erik Kessels, and Hicham Benohoud.

Re-contextualised

archival photographs, inclusive avatar modifications, karaoke-singing stuffed

animals, and giant medium format landscapes – Foto Industria: the VI Biennial

of Photography on Industry and Work, hosted at Fondazione MAST and across the

city of Bologna in various locations, has loosely connected a disparate

collection of artwork under the idea of game play. Although the

relationship between the exhibited works and this year’s theme of GAME is often tenuous, the festival offers an interesting insight into the breadth

of the game industry. Whilst some of the work deals with documenting

traditional game industries and the corresponding physical factories and

warehouses that historically made games, much of the work dances around this

idea of games or play in a more abstract way, pointing to the

tangible and intangible connections between labour and the city.

![]()

Fig.i

Revealing the scale of environmental impact and human labour connected to mass consumption, the most sombre exhibit on show is the work of German photographer Andreas Gursky, with a collection of large-format and digitally manipulated photographs. The visual power of Gursky’s images, which document industry’s impact on landscapes with immense scale and detail, maximises the opportunity of effect a gallery space can have on an individual; warping human scale under the weight of images with individual consumption as a starting point to explore the outcomes of excessive consumption and waste under global capitalism.

Although some of the photographs capture cityscapes, it is suburban and rural landscapes and architectures, often beyond public access, that capture the imagination. It feels perverse to play with these images, but it is through play that wider narratives are revealed, for example with a wall-filling image of an Amazon warehouse interior. Endless rows of products are organised algorithmically by popularity and relevance, rather than through traditional typologies, the company’s data driven categorisation system is revealed through the viewer playing this pattern game. Once the code is cracked, repeating products and patterns emerge – a mop sits next to a board game in one location, but elsewhere is found next to a squishy soft toy, somewhere else it neighbours a book.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Contrastingly, Erik Kessels’ series of intimate photographic portraits exhibited at Palazzo Magnani offer a human-scaled and deeply personal response to the games theme, a highlight of one of many exhibits presented in venues across the city centre. Told through a series of partner images, Carlo e Luciana tells the story of a married couple from the neighbouring town of Vinola who travelled the world taking photos of one another – the series of original images having been left to the artist by a neighbour after their passing.

Carlo and Luciana took turns posing in front of famous architectural landmarks and landscapes, the series resulting in a collection of identical scenes from the Great Wall of China to the Eiffel Tower, each of the couple appearing alone in diptych next to the other. Through the repeated framing, their relationship is documented through separation of the photographic act of being captured alone in a repeating rhythm.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Whether the game being played is by Carlo and Luciana, or by Kessels putting a private collection of amateur photography into a public gallery, the story told has stayed with me. Their inability to travel during their working years results in a forty-year gap in the collection – jumping from adventurous newlyweds to increasingly frail pensioners. In a world where popular architectural photography is dominated by the selfie and a desire to document oneself in front of a building or landscape, this collection is an original approach that deals with the human desire to document architecture through the lens of a personal relationship to the building. It also offers insight into an often-invisible relationship within architectural photography through documenting how our relationship with architecture shifts as we age, often constrained by the practicalities of mobility and labour practices.

“They travelled a lot after their retirement,” say Kessels, “they have albums of India, Cuba, Thailand, China... What’s interesting is, I have collected 15,000 family albums and 99% of them are fucking boring – only landscapes. Carlo and Lucia made use of the film at least!” That Carlo and Luciana, as civil servants with no artistic training, developed this practice of documenting the landscapes of their travels together and in private, makes this collection feel deeply intimate and a refreshing contribution to architectural photography – even if they might not have seen their work in this context.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

“I quite like how it’s almost a satirical work,” says Kessels, who describes himself as a photographer without a camera. He adds, “but I do think that it was a subconscious practice – because they had no children this was a practical thing to take turns in taking photos of each other.” It’s a shame that the physical curation of the show falls short, with the accompanying artist book that displays the photos side by side on the page succeeding where the large photo display boards awkwardly propped open in an internal courtyard struggle to maintain the photographic relationships.

![]()

![]()

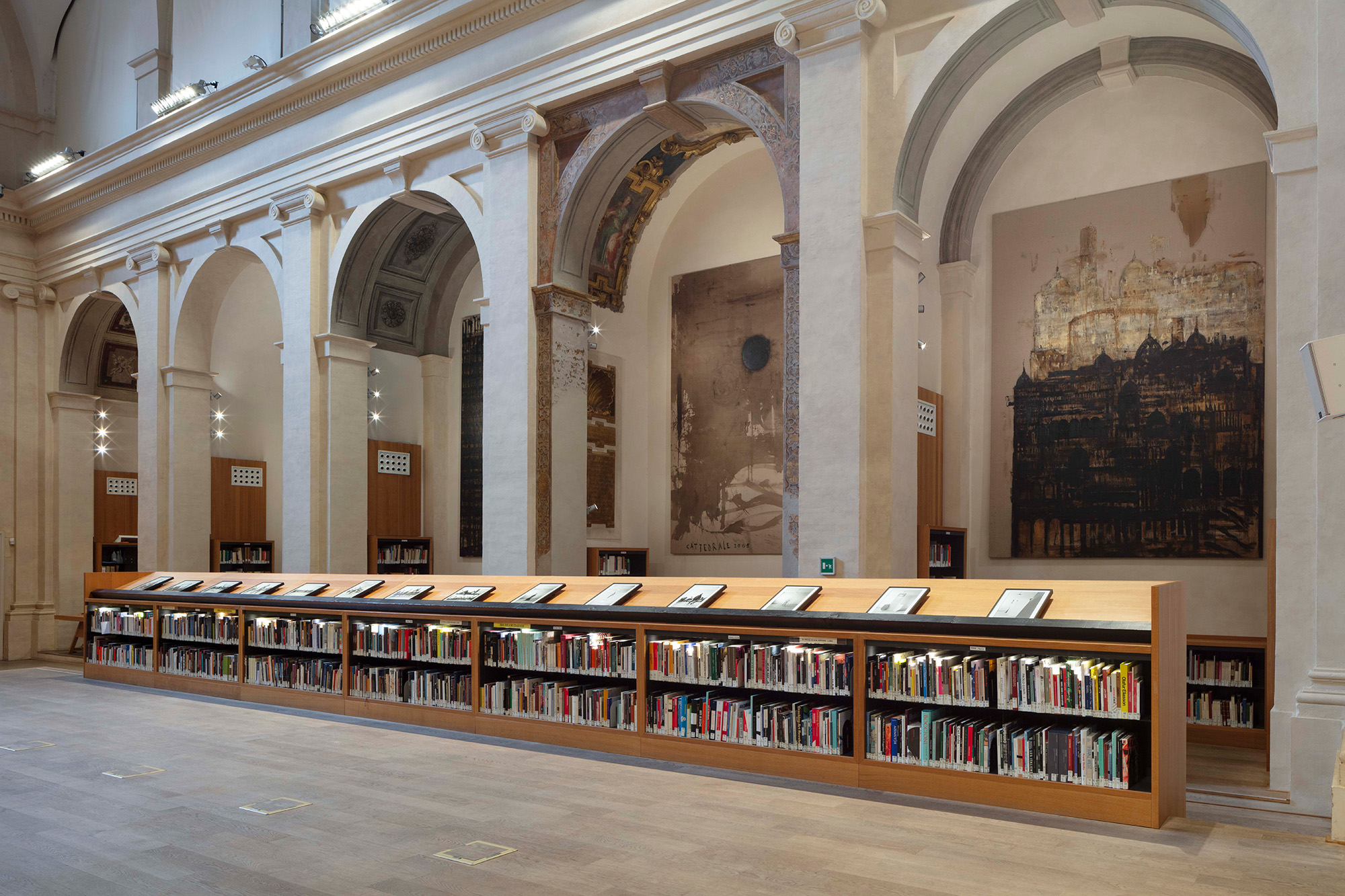

This appears as a common theme within the festival – the physical exhibition spaces often feeling rather clunky despite being hosted in a collection of classically stunning Italian villas, libraries, and museums. Perhaps the most successful in overcoming the challenges of hosting a contemporary art show in a listed building is the understated photography show of Hicham Benohoud, hosted in the San Giorgio in Poggiale Library. Capturing his students during his time as an art teacher in Marrakesh, his series of portraits are displayed like books under reading lights in the buildings central shelving platform. Documenting the children’s improvisation with classroom furniture and handmade wearable paper sculptures, game-play is wonderfully evident despite the seriousness of the subjects expressions.

Overall, the manipulation of architecture in slightly unexpected ways within the subject matter prove the most successful exhibits on show this biennial. Although more conventional representations of game-play can be found in the photographs of vacant playgrounds, the Las Vegas strip, and an abandoned pin-ball factory, the occupation of architecture in the work of Gursky, Kessels, and Benohoud offers diverse scales of subject matter and relations.

![]()

![]()

Fig.i

Revealing the scale of environmental impact and human labour connected to mass consumption, the most sombre exhibit on show is the work of German photographer Andreas Gursky, with a collection of large-format and digitally manipulated photographs. The visual power of Gursky’s images, which document industry’s impact on landscapes with immense scale and detail, maximises the opportunity of effect a gallery space can have on an individual; warping human scale under the weight of images with individual consumption as a starting point to explore the outcomes of excessive consumption and waste under global capitalism.

Although some of the photographs capture cityscapes, it is suburban and rural landscapes and architectures, often beyond public access, that capture the imagination. It feels perverse to play with these images, but it is through play that wider narratives are revealed, for example with a wall-filling image of an Amazon warehouse interior. Endless rows of products are organised algorithmically by popularity and relevance, rather than through traditional typologies, the company’s data driven categorisation system is revealed through the viewer playing this pattern game. Once the code is cracked, repeating products and patterns emerge – a mop sits next to a board game in one location, but elsewhere is found next to a squishy soft toy, somewhere else it neighbours a book.

Figs.ii-iv

Contrastingly, Erik Kessels’ series of intimate photographic portraits exhibited at Palazzo Magnani offer a human-scaled and deeply personal response to the games theme, a highlight of one of many exhibits presented in venues across the city centre. Told through a series of partner images, Carlo e Luciana tells the story of a married couple from the neighbouring town of Vinola who travelled the world taking photos of one another – the series of original images having been left to the artist by a neighbour after their passing.

Carlo and Luciana took turns posing in front of famous architectural landmarks and landscapes, the series resulting in a collection of identical scenes from the Great Wall of China to the Eiffel Tower, each of the couple appearing alone in diptych next to the other. Through the repeated framing, their relationship is documented through separation of the photographic act of being captured alone in a repeating rhythm.

Figs.v-viii

Whether the game being played is by Carlo and Luciana, or by Kessels putting a private collection of amateur photography into a public gallery, the story told has stayed with me. Their inability to travel during their working years results in a forty-year gap in the collection – jumping from adventurous newlyweds to increasingly frail pensioners. In a world where popular architectural photography is dominated by the selfie and a desire to document oneself in front of a building or landscape, this collection is an original approach that deals with the human desire to document architecture through the lens of a personal relationship to the building. It also offers insight into an often-invisible relationship within architectural photography through documenting how our relationship with architecture shifts as we age, often constrained by the practicalities of mobility and labour practices.

“They travelled a lot after their retirement,” say Kessels, “they have albums of India, Cuba, Thailand, China... What’s interesting is, I have collected 15,000 family albums and 99% of them are fucking boring – only landscapes. Carlo and Lucia made use of the film at least!” That Carlo and Luciana, as civil servants with no artistic training, developed this practice of documenting the landscapes of their travels together and in private, makes this collection feel deeply intimate and a refreshing contribution to architectural photography – even if they might not have seen their work in this context.

Figs.ix-xii

“I quite like how it’s almost a satirical work,” says Kessels, who describes himself as a photographer without a camera. He adds, “but I do think that it was a subconscious practice – because they had no children this was a practical thing to take turns in taking photos of each other.” It’s a shame that the physical curation of the show falls short, with the accompanying artist book that displays the photos side by side on the page succeeding where the large photo display boards awkwardly propped open in an internal courtyard struggle to maintain the photographic relationships.

Figs.xiii,xiv

This appears as a common theme within the festival – the physical exhibition spaces often feeling rather clunky despite being hosted in a collection of classically stunning Italian villas, libraries, and museums. Perhaps the most successful in overcoming the challenges of hosting a contemporary art show in a listed building is the understated photography show of Hicham Benohoud, hosted in the San Giorgio in Poggiale Library. Capturing his students during his time as an art teacher in Marrakesh, his series of portraits are displayed like books under reading lights in the buildings central shelving platform. Documenting the children’s improvisation with classroom furniture and handmade wearable paper sculptures, game-play is wonderfully evident despite the seriousness of the subjects expressions.

Overall, the manipulation of architecture in slightly unexpected ways within the subject matter prove the most successful exhibits on show this biennial. Although more conventional representations of game-play can be found in the photographs of vacant playgrounds, the Las Vegas strip, and an abandoned pin-ball factory, the occupation of architecture in the work of Gursky, Kessels, and Benohoud offers diverse scales of subject matter and relations.

Figs.xv,xvi

Fondazione

MAST (Manifattura di Arti, Sperimentazione e Tecnologia) is a non-profit

organisation founded in Bologna in 2013 that aims to promote social innovation

and corporate welfare projects to support collective economic, social, and

cultural growth. MAST is an internationally renowned cultural centre that

provides advanced welfare services for Coesia industrial group employees,

offering free cultural activities for the community focused on the arts and

photography on industry and work.

www.mast.org

Nyima

Murry is a British-Tibetan architectural designer, curator, and filmmaker. She

is currently undertaking a Masters in Landscape Architecture at the Bartlett,

UCL.

www.instagram.com/nyimamurry

www.instagram.com/nyimamurry