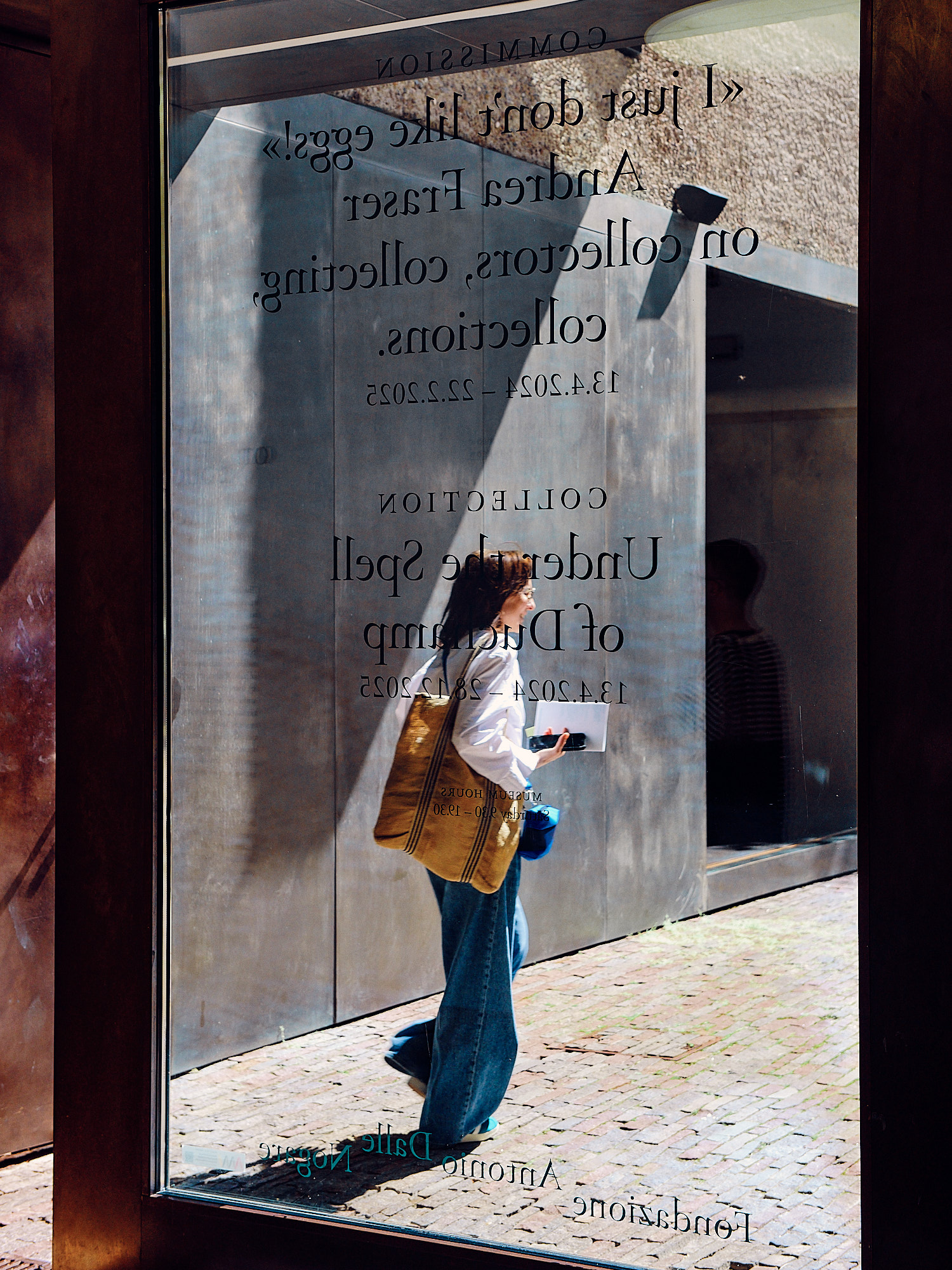

On architecture & collecting: Andrea Fraser at Fondazione

Antonio Dalle Nogare, Bolzano

Cut into the side of a hill, overlooking the South Tyrol

city of Bolzano, is the Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare, a private collection

of conceptual art. Editor of recessed.space, Will Jennings, visited to speak to

the founder, explore the building & take a look at two current exhibitions,

including a solo presentation from Andrea Fraser focusing on the nature of what

it is to collect.

There is an architectural model at the heart of Andrea

Fraser’s exhibition, I just Don’t Like Eggs. It shows a cascade of a

building down the side of a sloped site, a pitched-roof domestic building at

the top, then a flow of geometry, openings, angles, and retaining walls. The

model has a cut through its centre, which with an acute gaze the viewer can see

reveals rooms, stairwell and corridors deep within the hillside.

It is very meta. The model is a scale version of the very building it sits within, the gallery around it is being of those spaces seemingly carved into the incline. It’s an architectural study model of the Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare, designed by architects Walter Angonese and Andrea Marastoni, and it isn’t included in the exhibition only to show physical context, but also conceptual.

![]()

![]()

American artist Fraser takes interest the frameworks and systems surrounding the display of modern art, especially – and as is the focus in this exhibition – the role of art collectors. The title of the exhibition alludes to the language and stance of a collector, the phrase “I just don’t like eggs” taken from a version of the artist’s ongoing series of performance video works, May I Help You?. First dating from 1991, the four films made through to 2013 repeat actors speaking the same script, but playing different people in relation to the contemporary art world. Through changing the tone, language, and body, the performer speaks to different and conflicting points of view within the art world (and market). All four versions are shown here, including a 2011 version which tweaked the script to relate to architecture more than art, set within Rudolph Schindler’s house in LA, now the MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

It is the first curation of Fraser’s work which focuses specifically on ideas related to collectors, collecting, and collections. Curated by Andrea Viliani with Vittoria Pavesi, it is a mixed-media show of the artist’s video works, it includes a celebrated 2003 untitled work in which Fraser has sex with an anonymous collector who pre-agreed to purchase one of the five editions of the filmed encounter, a document that can speak to feminist ideas of the artist’s self-determination, but also of ideas of exchange, of art as service provision, and what it means to collect and own.

![]()

![]()

A wall work presents a vast grid of pie charts. 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics (2018) documents in blue and red the funding from boards of directors of 128 art museums to Republicans or Democratics in the year Donald Trump was elected President. It is part of deeper research by the artist into the relationship of politics, power, and culture, covering over 36,000 individual political contributions made, offering a new frame to consider the institutions that hold culture and perhaps reconsider an understanding of that culture shown within.

It is an exhibition that not only covers contemporary art and politics, but looks as far back as the hand-written inventory of over 45,000 objects from the collection of Sir Richard and Lady Wallace’s private mansion, which in 1900 became London’s public Wallace Collection museum. At the centre of the room is Um Monumento às Fantasias Descartadas (A Monument to Discarded Fantasies) (2003), a pile of costumes discarded on the ground after Rio de Janeiro’s carnival, where Fraser is the collector and artist, the clothes having finished their function as tools of escape and fantasy, redundant after the owners left carnival and returned to the everyday. Within such a data, research, performative, and playful interrogation of what it means to collect, the architectural model of Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare is afforded a rich context.

![]()

![]()

Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare, opened by the eponymous collector in 2018, is located in Bolzano, an historic northern Italian city close to the border with Austria. The hill, and Fondazione’s building that steps down it – as replicated in the model – can be found to the north of the Bolzano, overlooking the historic northern Italian along the path of the Torrente Talvera river. It is literally cut into the hillside, containing not only a suite of gallery spaces but also a vaulted storage space, cafeteria, library, and offices as well as a residential suite for Dalle Nogare’s son – who has carried on the interest and is studying architecture in London.

“At the beginning my dream was to become a tennis player,” Dalle Nogare says of an prowess that saw him make the national championships in Italy. “At 18 I was in the national team, and I had to decide – my father wanted me to study and start a company, but my dream was to become a tennis player.” After working for a short while as a tennis coach, Dalle Nogare began to work for his father’s marble company, but felt “it was a little too repetitive, always ‘buy the blocks, cut the blocks’.” He moved into a construction company that his father had a minority interest in, and here a new passion in architecture and construction developed.

![]()

![]()

![]()

While through his childhood his father had bought art for the family house, aged 21 with his own income he was able to dip into collecting for himself, predominantly 19th century local and German artists which. But as he travelled more he encountered contemporary art, and it opened up a new interest. “I was in New York at Dia Beacon and saw an incredible exhibition of Franz Erhard Walther,” the collector says, adding that “and I knew this was my dream, to have the money and build something similar for conceptual art.”

Dalle Nogare was involved in the design process alongside Walter Angonese and Andrea Marastoni. “we made the first drawings, then models, then bigger models,” he says of a process in which the concept was to create the building from materials excavated in situ: “We made a very large hole, 21 metres deep, we cut the rocks and used it to make the concrete.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

Two works in the collection are site-specific, including a Robert Barry window interrupting the mountain view from the library. Beyond, Instead, Possible… (2012) came from a conversation between the artist and Dalle Nogare, the matrix of colourful words speaking to the natural environment beyond. On the lawn outside is Dan Graham’s Bolzano Pavilion (2008), reflecting the weather, nearby vineyards, more distant mountains, and indeed the Fondazione’s architecture.

Inside, Dalle Nogare’s team manage the collection and curate it into themed exhibitions, as well as mounting guest shows such as Andrea Fraser’s I Just Don’t Like Eggs, alongside which a second exhibition, Under the Spell of Duchamp, is presented. Central to the display of conceptual works owned by the foundation is a 1958 version of one of Duchamp’s many La Boîte en Valise works, a dollhouse-scale portable museum-in-a-box containing accurate reproductions of classic works and from which curator Eva Brioschi has formed a wider exhibition.

The exhibition conceptually springs from this work, containing many great names and presenting a good representation of the kinds of artists and work Dalle Nogare started collecting after that 2012 trip to Dia Beacon. There is a 1963 Christo package (like those recently presented in East London by Gagosian, as we covered in 00136), Robert Breer’s 1970 Variations, small motorised plastic pieces that are set in a circle on the floor before, under their own whim, slowly move across the floor and break the order, with an attendant repeatedly reconstructing the circular neatness.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In another gallery, the galvanised steel ducts of Charlotte Posenenske’s Vierkantrohre Serie D (1967-2016) sit on the floor as out-of-place lumps of building, Marcel Broodthaers’ minimalist film Une Seconde d'Eternité (D'après une idée de Charles Baudelaire) (1970), and works from others including Daniel Buren, Gerard Byrne, Mario Garcia Tores, and Walter De Maria.

Whether through the Robert Barry work, reflected from the Dan Graham, or simply enjoyed from the terrace, the Fondazione offers long views towards the alps. Bolzano, acting as a bridge between northern and southern Europe, is mixed German and Italian speaking and the largest city in South Tyrol. Cable cars take visitors up into the surrounding mountains, offering views back into the city and towards the Dolomites, and, in the distance, the Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare, looking like a small architectural model on the hill.

![]()

![]()

![]()

It is very meta. The model is a scale version of the very building it sits within, the gallery around it is being of those spaces seemingly carved into the incline. It’s an architectural study model of the Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare, designed by architects Walter Angonese and Andrea Marastoni, and it isn’t included in the exhibition only to show physical context, but also conceptual.

American artist Fraser takes interest the frameworks and systems surrounding the display of modern art, especially – and as is the focus in this exhibition – the role of art collectors. The title of the exhibition alludes to the language and stance of a collector, the phrase “I just don’t like eggs” taken from a version of the artist’s ongoing series of performance video works, May I Help You?. First dating from 1991, the four films made through to 2013 repeat actors speaking the same script, but playing different people in relation to the contemporary art world. Through changing the tone, language, and body, the performer speaks to different and conflicting points of view within the art world (and market). All four versions are shown here, including a 2011 version which tweaked the script to relate to architecture more than art, set within Rudolph Schindler’s house in LA, now the MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

It is the first curation of Fraser’s work which focuses specifically on ideas related to collectors, collecting, and collections. Curated by Andrea Viliani with Vittoria Pavesi, it is a mixed-media show of the artist’s video works, it includes a celebrated 2003 untitled work in which Fraser has sex with an anonymous collector who pre-agreed to purchase one of the five editions of the filmed encounter, a document that can speak to feminist ideas of the artist’s self-determination, but also of ideas of exchange, of art as service provision, and what it means to collect and own.

A wall work presents a vast grid of pie charts. 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics (2018) documents in blue and red the funding from boards of directors of 128 art museums to Republicans or Democratics in the year Donald Trump was elected President. It is part of deeper research by the artist into the relationship of politics, power, and culture, covering over 36,000 individual political contributions made, offering a new frame to consider the institutions that hold culture and perhaps reconsider an understanding of that culture shown within.

It is an exhibition that not only covers contemporary art and politics, but looks as far back as the hand-written inventory of over 45,000 objects from the collection of Sir Richard and Lady Wallace’s private mansion, which in 1900 became London’s public Wallace Collection museum. At the centre of the room is Um Monumento às Fantasias Descartadas (A Monument to Discarded Fantasies) (2003), a pile of costumes discarded on the ground after Rio de Janeiro’s carnival, where Fraser is the collector and artist, the clothes having finished their function as tools of escape and fantasy, redundant after the owners left carnival and returned to the everyday. Within such a data, research, performative, and playful interrogation of what it means to collect, the architectural model of Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare is afforded a rich context.

Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare, opened by the eponymous collector in 2018, is located in Bolzano, an historic northern Italian city close to the border with Austria. The hill, and Fondazione’s building that steps down it – as replicated in the model – can be found to the north of the Bolzano, overlooking the historic northern Italian along the path of the Torrente Talvera river. It is literally cut into the hillside, containing not only a suite of gallery spaces but also a vaulted storage space, cafeteria, library, and offices as well as a residential suite for Dalle Nogare’s son – who has carried on the interest and is studying architecture in London.

“At the beginning my dream was to become a tennis player,” Dalle Nogare says of an prowess that saw him make the national championships in Italy. “At 18 I was in the national team, and I had to decide – my father wanted me to study and start a company, but my dream was to become a tennis player.” After working for a short while as a tennis coach, Dalle Nogare began to work for his father’s marble company, but felt “it was a little too repetitive, always ‘buy the blocks, cut the blocks’.” He moved into a construction company that his father had a minority interest in, and here a new passion in architecture and construction developed.

While through his childhood his father had bought art for the family house, aged 21 with his own income he was able to dip into collecting for himself, predominantly 19th century local and German artists which. But as he travelled more he encountered contemporary art, and it opened up a new interest. “I was in New York at Dia Beacon and saw an incredible exhibition of Franz Erhard Walther,” the collector says, adding that “and I knew this was my dream, to have the money and build something similar for conceptual art.”

Dalle Nogare was involved in the design process alongside Walter Angonese and Andrea Marastoni. “we made the first drawings, then models, then bigger models,” he says of a process in which the concept was to create the building from materials excavated in situ: “We made a very large hole, 21 metres deep, we cut the rocks and used it to make the concrete.”

Two works in the collection are site-specific, including a Robert Barry window interrupting the mountain view from the library. Beyond, Instead, Possible… (2012) came from a conversation between the artist and Dalle Nogare, the matrix of colourful words speaking to the natural environment beyond. On the lawn outside is Dan Graham’s Bolzano Pavilion (2008), reflecting the weather, nearby vineyards, more distant mountains, and indeed the Fondazione’s architecture.

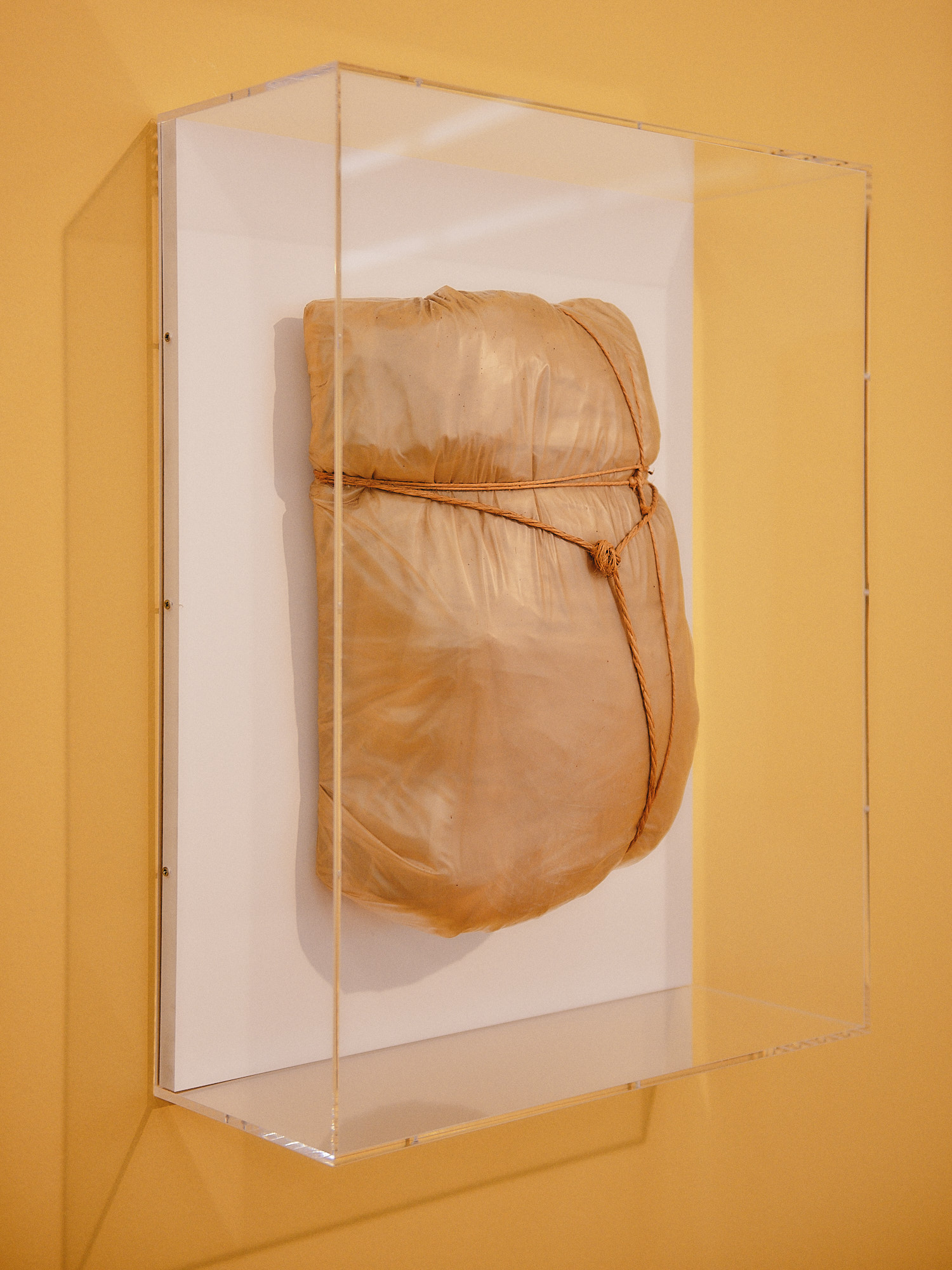

Inside, Dalle Nogare’s team manage the collection and curate it into themed exhibitions, as well as mounting guest shows such as Andrea Fraser’s I Just Don’t Like Eggs, alongside which a second exhibition, Under the Spell of Duchamp, is presented. Central to the display of conceptual works owned by the foundation is a 1958 version of one of Duchamp’s many La Boîte en Valise works, a dollhouse-scale portable museum-in-a-box containing accurate reproductions of classic works and from which curator Eva Brioschi has formed a wider exhibition.

The exhibition conceptually springs from this work, containing many great names and presenting a good representation of the kinds of artists and work Dalle Nogare started collecting after that 2012 trip to Dia Beacon. There is a 1963 Christo package (like those recently presented in East London by Gagosian, as we covered in 00136), Robert Breer’s 1970 Variations, small motorised plastic pieces that are set in a circle on the floor before, under their own whim, slowly move across the floor and break the order, with an attendant repeatedly reconstructing the circular neatness.

In another gallery, the galvanised steel ducts of Charlotte Posenenske’s Vierkantrohre Serie D (1967-2016) sit on the floor as out-of-place lumps of building, Marcel Broodthaers’ minimalist film Une Seconde d'Eternité (D'après une idée de Charles Baudelaire) (1970), and works from others including Daniel Buren, Gerard Byrne, Mario Garcia Tores, and Walter De Maria.

Whether through the Robert Barry work, reflected from the Dan Graham, or simply enjoyed from the terrace, the Fondazione offers long views towards the alps. Bolzano, acting as a bridge between northern and southern Europe, is mixed German and Italian speaking and the largest city in South Tyrol. Cable cars take visitors up into the surrounding mountains, offering views back into the city and towards the Dolomites, and, in the distance, the Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare, looking like a small architectural model on the hill.

Andrea Fraser

was born in Billings, Montana, USA (1965) and currently lives and works in Los

Angeles, California, USA. She is a Professor in the Department of Art at the

University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) School of the Arts and

Architecture. Since the mid-1980s, her groundbreaking work in institutional

critique has positioned Fraser as one of her generation’s most influential and

provocative artists. She has used performance, video, text, and a range of

other mediums to explore the motivations of artists, collectors, gallerists,

patrons, and art audiences, from financial investment to the pursuit of

prestige, from sexual fantasy to self-fulfillment. Combining the

site-specific and research-based approaches of conceptualism with feminist

investigations of subjectivity and desire, Fraser's work is infused with

incisive analysis, humor, and pathos. The result was described by Pierre

Bourdieu as "a sort of machine

infernale whose operation causes the hidden truth of social reality to

reveal itself." Fraser's work has been exhibited in solo exhibitions,

amongst many others, at: the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA (2022); the

Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art, PA, USA and Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, Germany

(2021); the Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA and the Whitney Museum of

American Art, New York, USA (2016); Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig,

Wien, Austria (2012); and at Harvard University, MA, USA (2010). Retrospectives

of her work have been presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art Barcelona, Spain,

and MUAC UNAM Mexico City, Mexico (2016); the Museum der Moderne Salzburg,

Austria (2015); Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany (2013), and at the Kunstverein,

Hamburg, Germany (2003). In 1993 she represented Austria in the

45th Venice Biennale alongside Christian Philipp Müller and Gerwald

Rockenschaub. She participated in the 1993 and 2012 Whitney Biennial

exhibitions, the 1998 and 2021 editions of the Bienal de São Paulo, Prospect 3

New Orleans in 2014, and the 12th Shanghai Biennale in 2018. Her project

in Museums, Money, and Politics (2018)

was named the best art book of the decade by ARTnews. Fraser was the recipient of numerous awards,

including: the Foundation for

Contemporary Arts Fellowship (2017); the Oskar Kokoschka Prize, Vienna, Austria (2015); the Wolfgang Hahn Prize, Cologne, Germany

(2013); the Anonymous was a Woman

Fellowship (2012); the Art Matters

Inc. Fellowship (1996-1997, 1990-1991, 1987-1988); the National Endowment for the Arts Visual Arts Fellowship (1991-1992);

and the Franklin Furnace Fund for

Performance Art Award (1990-1991).

www.mariangoodman.com/artists/andrea-fraser

www.nagel-draxler.de/artist/andrea-fraser

Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare was established to

promote contemporary art as a language for interpreting changes in society, as

a tool for promoting interaction between art, architecture, innovation and

artistic research and as a means of bringing an increasingly wider public

closer to the contemporary art. The Foundation’s actions

are characterised by: its focus on future generations; its continuous research; its dynamic social and cultural context for the whole

community; and, its connections with international and local stakeholders.

The Foundation operates

in three ways: interaction with international and local artists; experimentation through innovative exhibition projects, a

public program and a specialised library; and, education through meetings and initiatives aimed at raising

and broadening the awareness of contemporary art.

www.fondazioneantoniodallenogare.com/en

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.fondazioneantoniodallenogare.com/en

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

Andrea Fraser, I Just Don’t Like Eggs!, runs until 22

February 2025, while Under the Spell of Duchamp runs until 28 December

2025.

Information on both exhibitions as well as the Fondazione Antonio Dalle

Nogare can be found at: www.fondazioneantoniodallenogare.com/en

images

All photographs © Carlo Zambon.

publication date

17 May 2024

tags

Walter Angonese, Robert Barry, Bolzano, Robert Breer, Marcel Broodthaers, Christo, Collecting, Collections, Collectors, Conceptual art, Construction, Antonio Dalle Nogare, Dia Beacon, Dolomites, Marcel Duchamp, Franz Erhard Walther, Andrea Fraser, Dan Graham, Will Jennings, Andrea Marastoni, MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Model, Money, Politics, Charlotte Posenenske, Rudolph Schindler, Tennis

Information on both exhibitions as well as the Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare can be found at: www.fondazioneantoniodallenogare.com/en