An interview with Derrick Adams on the spaces of Black America

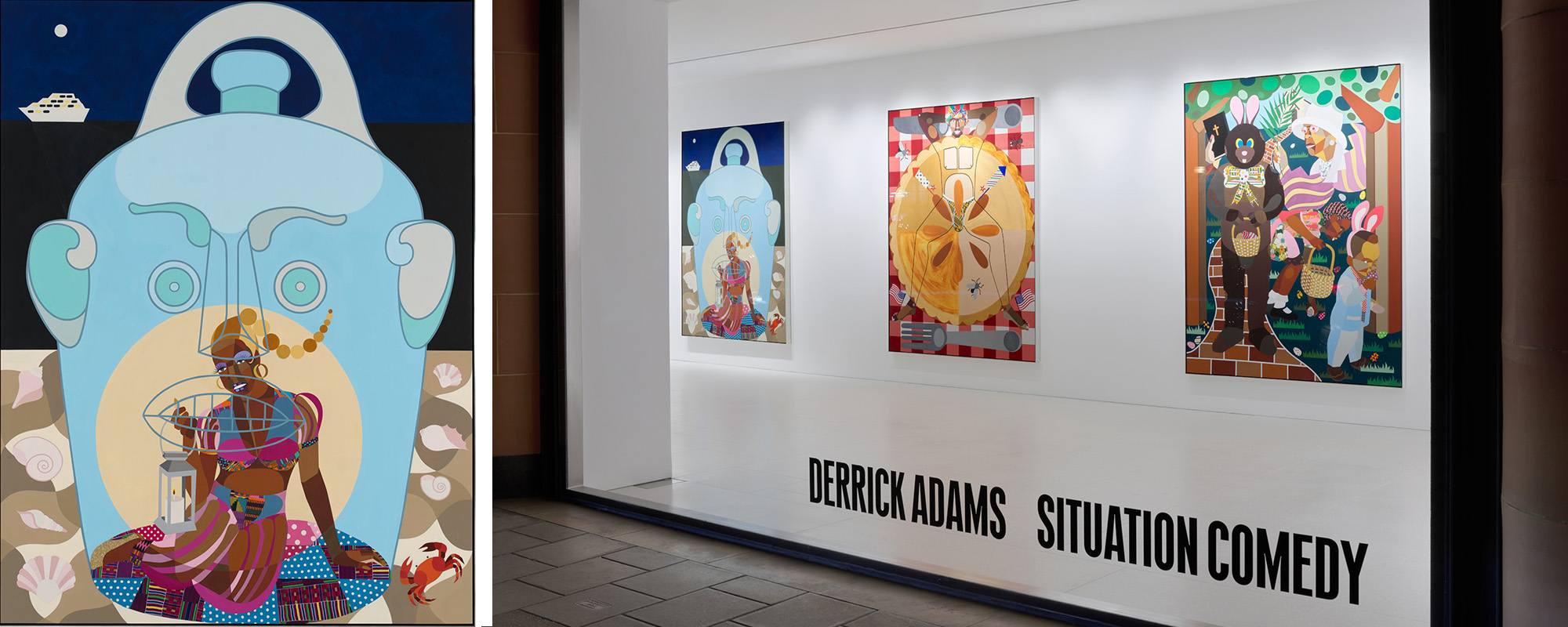

Derrick Adams is not only an artist, but he is also a community builder in his home city of Baltimore where he is behind two separate projects to support the history & future of Black artists & residents. His artworks riff off American themes, joyfully conflating the nation’s complicated racial history with iconic brands & symbols into a pop aesthetic. Will Jennings sat with the artist on the occasion of a presentation of his work at Gagosian in London to find out more.

Editor of recessed.space Will Jennings interviewed Baltimore-based artist Derrick Adams at the opening of his exhibition Situation Comedy, presented at Gagosian’s Davies Street space in London from 13 February to 29 March, 2025 (details here).

Adams’ paintings present imagined scenes from Black Americana, imbued with feelings of leisure and relaxation. There are also ideas of consumerism – present through material objects such as Dominos Sugar and a bag designed by Telfar Clemens – that speak to contemporary notions of escape, even if it comes with history and political weight.

![]()

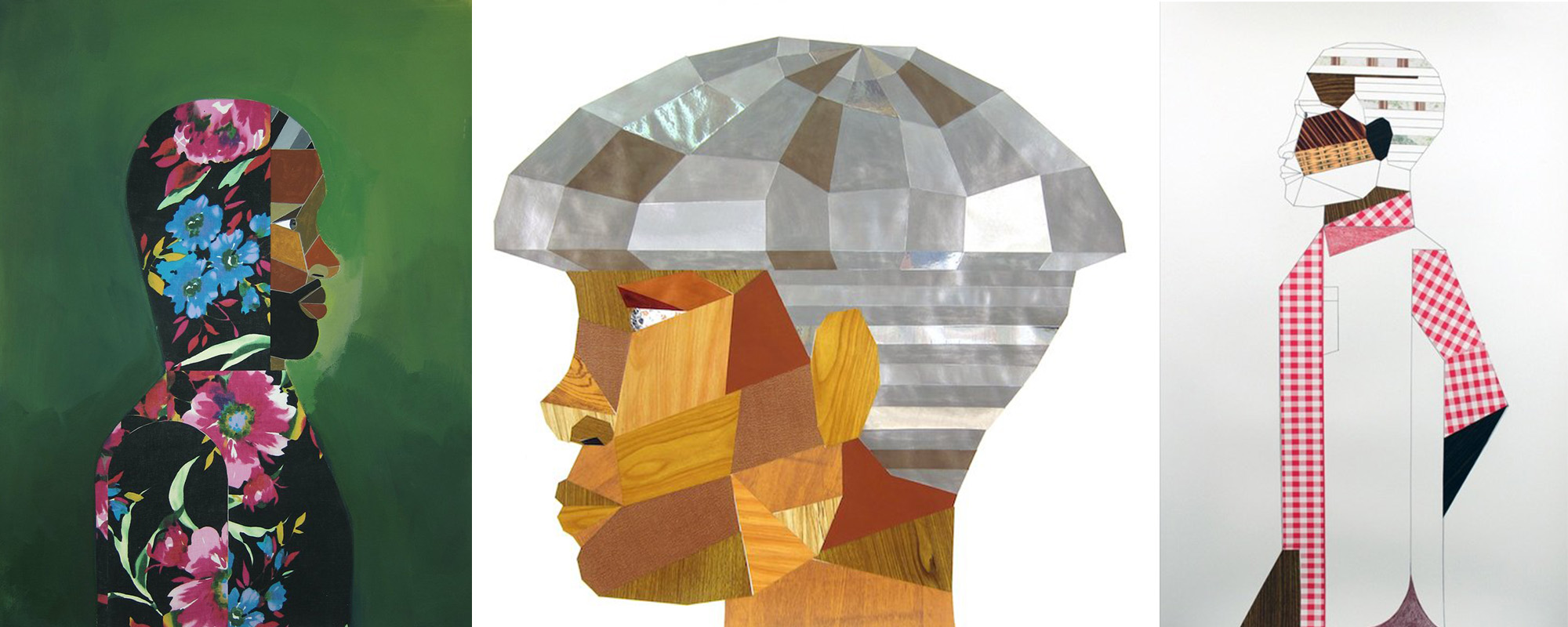

figs.i,ii

Previous projects also look at the Black figure, as well as Black history – here we also discuss with Adams his 2018 body of work, Sanctuary, a three dimensional reimagination of the Negro Motorist Green Book, an annual guidebook for Black American road-trippers published by New York postal worker Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1967, during America’s Jim Crow era. It is one of many exhibitions by Adams that create three dimensional space and sculpture with flat painted works.

Away from painting, Adams also founded The Last Resort Artist Retreat, a residency in Baltimore for Black creatives not as a space for making, but for escape and relaxation using the concept of leisure as therapy through curated experiences conducive to rejuvenation. He is also behind the Black Baltimore Digital Database, a digital home for citizen history and social memory as a counter-institutional space for collecting, storing, and safekeeping data from local archival initiatives.

While not specifically about architecture or the built environment, all Adams’ works and initiatives have a deep interest in the subjects, and this is where we started the conversation:

This interview was originally published in May on A Deeper Recess, the reader-supported newsletter from recessed.space that runs parallel to the free news update bulleting, The Recess, delivered straight to your inbox.

Please consider subscribing to A Deeper Recess to help support independent writing on art and architecture, more details available HERE.

In earlier works I was interested in architecture and would meet with architect friends. A series titled Deconstruction Worker was directly comparing the body to architecture and how architecture is informed by the human body, versus how the human body is influenced by architecture. Places are built based on the scale of the figure, the way they move, the way they occupy space and gather. Especially with urban spaces, places are designed to assist in the movement of where bodies go and how they operate - sometimes negatively, sometimes positively.

![]()

figs.iii-v

So when I started making the Deconstruction Workers I created categories including floor plans, elevation sections, and the presentation. I was making large heads out of woodgrain and wood-printed shelf-liner so it was like looking down into a building. The sections were more angular where figures were open, with things established inside. Then the presentation was the actual human body coexisting in the interior/exterior space - the body as the building. I was working on making these works and creating this language that I think has somewhat situated this work in the way that it exists.

With this piece, Getting the Bag (2024) there's a small Telfar bag hanging from the eagle's mouth – that was a riff off Rauschenberg's Canyon (1959) painting with an eagle [see here], that in turn was influenced by a Rembrandt painting of the eagle [The Rape of Ganymede (1635) - see here]. So, I was thinking about contemporary culture and how that would relate to the context of those paintings. I think that the origin that I took away from looking at both Rauschenberg’s and Rembrandt’s paintings, even though they have their own ideology behind them, is the desire to consume youth culture, it's about the desire of something that is old, or something considered fleeting, something that understands the origin of youth as a virtue.

![]()

figs.vi,vii

I think that in our contemporary culture, youth culture was established associated with objects, things that identify with what young people want, so instead of using the pillow that Rauschenberg had hanging from the eagle's mouth, I thought it would be interesting to bring in this Telfar bag. I do things like that to help connect to the narratives of the past, to bring certain histories forward in a way that might normally be in a very academic, literal manner.

Then the environment around the figure relates to the iconography people associate with the Americas - the canyon and the teepee – and then I added smoke signals, which could mean a lot of different things. it could be a warning!

![]()

fig.viii

Colour is very important – a lot of the works take a much longer time because of my interest in colour, because the works are created flat and the colour creates the space, or at least a suggestion of space and volume.

I think the simplicity of the way I work creates planes that can exist – like the way the ground is green, it almost seems like it opens up for the viewer to step into, because of how it appears to spread from the panel into the space of the gallery that we're in.

![]()

figs.ix,x

I have artist friends who go to the museum, they look at Renaissance or Victorian paintings, and their work is focused on that as the premise of disruption. I don't think like that. I think there's experiences I've had, of people I know who are not privileged or prioritised, and I think as artists we have to speak on those things in our work. This was an opportunity to highlight the formal aesthetics of things that I think are not necessarily highlighted, because sometimes the story behind why people with traumatic or marginalised experiences will help people understand why they made it.

![]()

figs.xi,xii

I think that even though these paintings are flat, with colour and shape I'm able to suggest certain levels of space in the way viewers move through it. I manipulate the scale of things to appear larger and smaller in ways that are not necessarily realistic. That's what I think about most of the time when working – that the subject matter and the suggested narrative that may be attached to it is something I don't have to think that much about. Fortunately – and unfortunately – as Black artists, everything we see is political, so I don't have to think about politics…

![]()

figs.xiii,xiv

I actually think of myself more as an abstract artist. A lot of my paintings could be abstracts if I remove the figure, if I removed all the things people use to identify place, it would just be more suggestive an environment or architectural framework.

The cruise ship is going by, casting light, so it's like every scene has its own reality. The bottle is about self-containment versus imposed-containment.

![]()

It’s like sugar, or coffee, or even our phones, can be so attached to our desire to enjoy, that the history of how it came to exist is embedded in its fabric. Like a string from a sweater, if you pull it the whole thing comes apart, it's not sweater anymore. And both things are very American – the Kool Aid the face vessel – so I thought they were really interesting. And then the environment around them, I think, created a sense of place without making these two objects literal.

We have a headquarters from where all our programmes operate from, a landmark building we are using. It's like our HQ to establish the community engagement, but moving forward we want to build a physical space. The Retreat should really be a genuine place of leisure.

Adams’ paintings present imagined scenes from Black Americana, imbued with feelings of leisure and relaxation. There are also ideas of consumerism – present through material objects such as Dominos Sugar and a bag designed by Telfar Clemens – that speak to contemporary notions of escape, even if it comes with history and political weight.

figs.i,ii

Previous projects also look at the Black figure, as well as Black history – here we also discuss with Adams his 2018 body of work, Sanctuary, a three dimensional reimagination of the Negro Motorist Green Book, an annual guidebook for Black American road-trippers published by New York postal worker Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1967, during America’s Jim Crow era. It is one of many exhibitions by Adams that create three dimensional space and sculpture with flat painted works.

Away from painting, Adams also founded The Last Resort Artist Retreat, a residency in Baltimore for Black creatives not as a space for making, but for escape and relaxation using the concept of leisure as therapy through curated experiences conducive to rejuvenation. He is also behind the Black Baltimore Digital Database, a digital home for citizen history and social memory as a counter-institutional space for collecting, storing, and safekeeping data from local archival initiatives.

While not specifically about architecture or the built environment, all Adams’ works and initiatives have a deep interest in the subjects, and this is where we started the conversation:

This interview was originally published in May on A Deeper Recess, the reader-supported newsletter from recessed.space that runs parallel to the free news update bulleting, The Recess, delivered straight to your inbox.

Please consider subscribing to A Deeper Recess to help support independent writing on art and architecture, more details available HERE.

This exhibition is less architectural than previous bodies of work, but it's very space-based, it's about place.

I think about architecture all the time. I think about interior/exterior space, domestic space, shared space. I use rulers a lot, I use different mathematical processes associated with architecture. I think about these things a lot and I don't really think that you cannot incorporate those things if you have an academic experience with art through institutional influence, there's no way that you can make these types of works without somehow calling on influences based on years of looking at slides of paintings and art. It comes through in the work, even unintentionally, because that's basically how artists learn and train their decision making in composition – we become aware of the way space is established through line and colour.In earlier works I was interested in architecture and would meet with architect friends. A series titled Deconstruction Worker was directly comparing the body to architecture and how architecture is informed by the human body, versus how the human body is influenced by architecture. Places are built based on the scale of the figure, the way they move, the way they occupy space and gather. Especially with urban spaces, places are designed to assist in the movement of where bodies go and how they operate - sometimes negatively, sometimes positively.

figs.iii-v

So when I started making the Deconstruction Workers I created categories including floor plans, elevation sections, and the presentation. I was making large heads out of woodgrain and wood-printed shelf-liner so it was like looking down into a building. The sections were more angular where figures were open, with things established inside. Then the presentation was the actual human body coexisting in the interior/exterior space - the body as the building. I was working on making these works and creating this language that I think has somewhat situated this work in the way that it exists.

This idea of interior and exterior space is something that runs through your work - that the body is in a space, but in the painting, we're also seeing what's inside the head, the mind, and the experience of the person. There's something here about the psychology of space and the physicality of space.

I'm always thinking about where the figures fit in, and I rarely disassociate the figure with the environment that they occupy. Because of that reason it established a suggestion of narrative but, for the most part, my work is not necessarily linear-narrative based. It's more about using the language that I associate with place to insinuate a story the viewer can establish on their own – or not. But it's not that I want the viewer to take away any particular beginning or end. Which is present in some of these works.With this piece, Getting the Bag (2024) there's a small Telfar bag hanging from the eagle's mouth – that was a riff off Rauschenberg's Canyon (1959) painting with an eagle [see here], that in turn was influenced by a Rembrandt painting of the eagle [The Rape of Ganymede (1635) - see here]. So, I was thinking about contemporary culture and how that would relate to the context of those paintings. I think that the origin that I took away from looking at both Rauschenberg’s and Rembrandt’s paintings, even though they have their own ideology behind them, is the desire to consume youth culture, it's about the desire of something that is old, or something considered fleeting, something that understands the origin of youth as a virtue.

figs.vi,vii

I think that in our contemporary culture, youth culture was established associated with objects, things that identify with what young people want, so instead of using the pillow that Rauschenberg had hanging from the eagle's mouth, I thought it would be interesting to bring in this Telfar bag. I do things like that to help connect to the narratives of the past, to bring certain histories forward in a way that might normally be in a very academic, literal manner.

But within this piece, the viewer can create various narratives - especially now we're talking about the body in space. This is Americana, and the eagle carries a lot of symbolism with how it's used politically, especially now. And here there's a black cowboy in a landscape full of indigenous history as well.

There's been rumoured history that the Lone Ranger, an American bounty hunter, was a black person and it's documented that he used a tactic of capturing outlaws where he wore various disguises, and instead of giving people the silver bullet, he would give a silver coin. There are certain things that could be factual, could be folklore, but the fact is that these stories are out there in conversations to consider. For me, it's like putting placeholders in for things that I'm thinking about but aren’t necessarily as intended for the viewer to be aware of or to have familiarity with. For me, it’s about looking beyond the surface and going deeper. When I'm making paintings, I usually start with one figure, one thing.So you have the idea of a single placeholder, which here was the eagle, or the Lone Ranger?

It was the Lone Ranger and then I incorporated the eagle in a kind of embrace. He's hugging the eagle, and the eagle is in drag, it's made up, is elaborate and gaudy. And that's what I think about America sometimes! It can be very campy, or very loud, and to some people those very desirable and provocative. Some people are more turned off by it.Then the environment around the figure relates to the iconography people associate with the Americas - the canyon and the teepee – and then I added smoke signals, which could mean a lot of different things. it could be a warning!

fig.viii

There are a lot of elements which in 2025 could be seen as a warning, or a message.

When I make work, I'm listening to music, reading different things, in conversation with artists who come to my studio - friends, writers, musicians – and we talk about a lot of different things. I think this all seeps into the work subconsciously, but honestly when I'm making work my main motivation is strictly formal, making things flow or connect.Colour is very important – a lot of the works take a much longer time because of my interest in colour, because the works are created flat and the colour creates the space, or at least a suggestion of space and volume.

This connects to your interest in Sol LeWitt?

Sol LeWitt, Jacob Lawrence, artists who work with colour as a way of establishing ground and space – Sol with a more abstract, formalised approach. When I create something like Canyon, it's more in line with the way Sol would establish a simplistic line and I think about that when I'm making works because I like simplicity as a way of complicating the viewer's experience. I think that when works are dense and convoluted with imagery, it can actually flatten the work – people think it becomes dense with a complicated experience for the viewer, but it can actually make the viewer feel like a spectator and not necessarily part of the experience.I think the simplicity of the way I work creates planes that can exist – like the way the ground is green, it almost seems like it opens up for the viewer to step into, because of how it appears to spread from the panel into the space of the gallery that we're in.

figs.ix,x

And this work, Baked In (2024), riffs off da Vinci's Vitruvian Man, but layers in Americana – and a pie!

He's supposed to be part of the ingredient of the pie, right? He's baked into the pie! His body, the outline, is the impression of his body existing – some elements are protruding out, which is this kind of Kente printed material associated with the African continent. But I also use it for geometric formation – there are certain geometric formations in African fabric where I think there is important juxtaposition, it gives the viewer understanding of the formal tradition that makes up the pattern. The way the grid operates with more organic shapes, they both embody a particular thing and together they allude to architectural compositions. I use them a lot, because I think they mimic my drawings, and the way that I create space. But also the juxtaposition acts as a placeholder for the experience of Black Americans.There's something about how architectural and urban space is built around the human form and body – that starts with the Vitruvian Man, but it’s an ongoing critique in architecture that the perfect man, whether Corbusier or any white male of a certain size, builds the world around them.

Those works were centred around a subject of a primary figure, reflective of my primary figure. I think that when those works were created by those individuals, they were they were really cantering themselves as the primary figure, which would be normal, and I think that if anything it gives me the same level of liberty and empowerment to be very deliberate in the way that I take charge of creating imagery more reflective of what I think people I want to see. The things that inform the way I make work psychologically, subliminally, those things – I cannot separate myself. But it also gives more to work from and work away from.I have artist friends who go to the museum, they look at Renaissance or Victorian paintings, and their work is focused on that as the premise of disruption. I don't think like that. I think there's experiences I've had, of people I know who are not privileged or prioritised, and I think as artists we have to speak on those things in our work. This was an opportunity to highlight the formal aesthetics of things that I think are not necessarily highlighted, because sometimes the story behind why people with traumatic or marginalised experiences will help people understand why they made it.

figs.xi,xii

It's not just historical artworks or symbols, but also people and places. You have the Lone Ranger as a Black man in landscape here, but your previous work, Sanctuary, talks about the road, and the idea of the American road trip, which we are familiar with but always by a white man or woman – with your work around the Green Book, you were saying that it is a landscape for Black Americans too.

Yes. That body of work was first shown at the Museum of Art and Design in New York (see here). I felt that the makers of the Green Book, New York postal worker Victor Hugo Green and his wife, considered it a design project and I thought that no one ever spoke about their accomplishment as designers. It was always considered regarding the significance of its usage, but there was room to think about the aesthetic principles that went into creating it, from two people who are not necessarily considered design publishers. I thought my contribution would bring the directory to life more than focusing on the traumatic history that drove them to make it.And you made that work in three dimensions.

I wanted to make almost a pop-up book, where the architectural elements of some of the structures that made accessible through their publication. That was challenging, because when you start with a reference that is not necessarily visual, most people don't think of it as a visual experience, so I was trying to elevate people's understanding of the importance of their work as an object.Exhibitions about books can often be the hardest to make, curators often resorting to putting the books on shelves and opening them up. But it reminds us that your practice is sculptural, three dimensional, public space works, and those which can be inhabited. This is also present in your works of domestic living spaces.

When I'm making sculptural objects, they're usually interactive or participatory in some way, or they consider the viewer as they move through the space, so the viewer becomes the activation of the work. I cannot make flat painted work without also making three dimensional pieces, because they help me understand space in a way that I would not be able to if just making paintings as illustrations of space.I think that even though these paintings are flat, with colour and shape I'm able to suggest certain levels of space in the way viewers move through it. I manipulate the scale of things to appear larger and smaller in ways that are not necessarily realistic. That's what I think about most of the time when working – that the subject matter and the suggested narrative that may be attached to it is something I don't have to think that much about. Fortunately – and unfortunately – as Black artists, everything we see is political, so I don't have to think about politics…

You have the American eagle in drag, that is quite political!

It's always an insinuation that I'm trying to be political. But I think that with that knowledge of the way I am being perceived, it frees me up a lot to just have fun in my studio and to make things that I know will be read in different ways.

figs.xiii,xiv

Tell me about your aesthetic process.

I use a lot of different clip art references for some of the smaller elements – here, for example, the canyon is from clip art! I use a lot of really flattened images that are considered iconography, things that are symbolic, which in a way takes away all of the deep, overly-detailed things. As I'm moving things around and establishing arrangements, I want something that is the most simplistic shapeI actually think of myself more as an abstract artist. A lot of my paintings could be abstracts if I remove the figure, if I removed all the things people use to identify place, it would just be more suggestive an environment or architectural framework.

These paintings are all places – the canyon, the beach – but they are also, as we mentioned, psychological spaces, many of them are places of escape, such as alone on the night time beach, or like this dream space. Is there something here about escaping from the world into an inner world, one of leisure and freedom, places which are abstract.

This actually references a face vessel, associated with early 1800s America. Enslaved Africans would make vessels to put on graves to ward off evil, or which would be used for medicinal reasons, they were a common practice to make. The more exaggerated the face, the more powerful it would be to ward off evil spirits. She's inside the bottle, and she's not necessarily trying to be discovered, she's fine.The cruise ship is going by, casting light, so it's like every scene has its own reality. The bottle is about self-containment versus imposed-containment.

figs.xv,xvi

There are many narratives in the works. In another work you've got Domino Sugar. Some of these ingredients don’t have to be complex, a curator may not be needed to understand them.

There is a very interesting history of sugar and labour that was a motivation for inserting it into the work. But in the same painting I incorporate the face vessels, so was more that there are certain things that have a dramatic history, but they're covered with sweetness, or how something cannot be separated from its creation from trauma. I know it came from this terrible place, but it tastes so good and I gotta keep drinking it!It’s like sugar, or coffee, or even our phones, can be so attached to our desire to enjoy, that the history of how it came to exist is embedded in its fabric. Like a string from a sweater, if you pull it the whole thing comes apart, it's not sweater anymore. And both things are very American – the Kool Aid the face vessel – so I thought they were really interesting. And then the environment around them, I think, created a sense of place without making these two objects literal.

Tell me about The Last Resort Artist Retreat in Baltimore, and also the Black Baltimore Digital Database.

The concept of both have an academic component. At the Retreat (see here), we tend to have people who are from academic backgrounds – artists, writers – working there and running the centre. The Database (see here) was really thinking about how regular citizens archive their stuff – it’s more like a modern day scrapbooking club.Which I think is important at a time when certain people are trying to take down Wikipedia, the Internet Archive, or even the US National Archives. It’s important that not only the big things, but everyday lives are documents.

Through programming, I am trying to convince the citizens of Baltimore how to socialise. How with basic gatherings where the topic could be safekeeping archive, or where people have moral storytelling and older citizens might come and talk about when they grew up, what was going on in the neighbourhood, the street they lived on. We find out about where people lived and how they moved from here to there and I find you get more sharing in a comfortable, social space rather than a more academic space.We have a headquarters from where all our programmes operate from, a landmark building we are using. It's like our HQ to establish the community engagement, but moving forward we want to build a physical space. The Retreat should really be a genuine place of leisure.

At a time when it's really hard to relax, you're putting intellectual, intelligent, creative people in a room and asking them precisely to do that, in 2025, with everything going on.

Also, it's challenging for people who work there to understand that they are not the participants, but that they are working, and even though everyone else is relaxing, their job is to facilitate the relaxation. Their job is to create opportunities for them, to create structure that visitors can step in and out of – the weekly meal, or yoga, meditation… They don't have to attend, but they have options.This speaks to many of your paintings, to finish up, that in one canvas you have the ingredients for other narratives and journeys that viewers might want to go on – the Telfer bag, the cowboy, the eagle, indigeneity – but you're not telling the visitor to go to any one of them. It's up to them, you've just given a structure and options.

Yeah, I guess that's what I'm doing. I give you the options to take part, or opt out. So I definitely feel like this mirrors what I'm doing with my Baltimore nonprofit, but I think this is way more gratifying, I have more control over the painting because it is something coming from me directly.

Derrick Adams

was born in Baltimore in 1970,

and lives and works in New York. Collections include the Baltimore Museum of

Art; Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond;

Brooklyn Museum, New York; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Studio Museum

in Harlem, New York; and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Exhibitions

include ON, Pioneer Works, New York (2016); Network,

California African American Museum, Los Angeles (2017); Patrick Kelly,

The Journey, Studio Museum in Harlem/Countee Cullen Library, New York

(2017); Sanctuary, Museum of Arts and Design, New York

(2018); Transmission, Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver

(2018); Where I’m From, Baltimore City Hall (2019); Buoyant,

Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York (2020); Derrick Adams and

Barbara Earl Thomas: Packaged Black, Henry Art Gallery, Seattle

(2021); LOOKS, Cleveland Museum of Art (2021–22); and I Can

Show You Better Than I Can Tell You, FLAG Art Foundation, New York (2023).

Adams has received the Louis Comfort Tiffany Award (2009), Joyce Alexander Wein

Artist Prize from the Studio Museum in Harlem (2016), Gordon Parks Foundation

Fellowship (2018), and Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Residency (2019).

www.derrickadams.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett & is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info