Birmingham to Wonderland: Cinema in the second city

An exhibition in the city’s Museum and Art Gallery, curated by Flatpack Festival, explores Birmingham’s deep relationship to cinema. From the first flickbook to contemporary pop-up community film, the city is also where the Odeon chain was born, setting a deco aesthetic forever synonymous with UK cinema.

Los Angeles, Berlin, Venice, Cannes – there are cities in

the world synonymous with film. Birmingham

may not be top of your list, but an exhibition in the city’s Museum and

Art Gallery is packed with anecdotes and artefacts documenting now only how

film has been received amongst the communities who have lived there, but also

how Birmingham has impacted the story of film.

Curated by Flatpack Festival, an annual two-week long celebration of all things moving image, the exhibition Wonderland finds a local perspective on a global artform, but which speaks wider than the M5, M6, and M42 bounding the city, and into social and architectural realms.

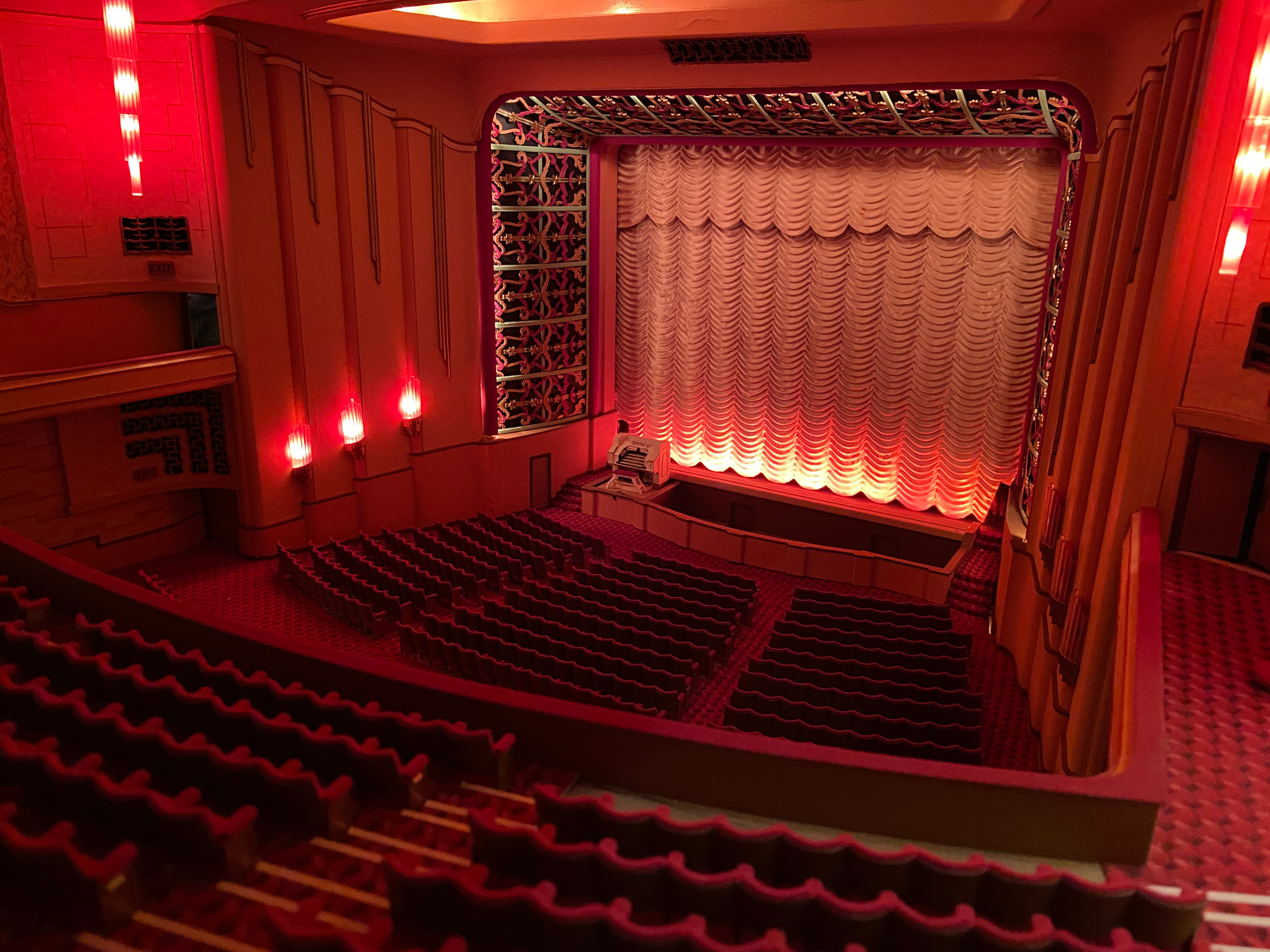

The initial hook for the story of film in Birmingham is Odeon, the now-international cinema chain which was born from the Midlands city from the 1930s and became synonymous with the mass-growth of the artform in the modern age, suitably using deco Moderne as an architectural language. The company was formed by Oscar Deutsch, bored by the metal industry which had given him money but not intellectual curiosity, and as a film-fan set out to make cinemagoing a whole new experience for a generation and beyond.

![]()

Deutsch, born in the Balsall Heath area of the city in 1895, began his cinema career in 1925, renting three Midlands cinemas as a business interest, before shortly after opening his first in Dudley in 1928. In less than a decade the Odeon chain (the idea that the name is an acronym of Oscar Deutsch Entertains Our Nation is an urban myth) grew to over 250 cinemas across the country, opening three brand-new cinemas a week at the peak.

As part of the festival there was a talk historian Allen Eyles who took the audience through the changing architectural language of many of those cinema buildings, from initial middle-English and Moorish typologies and then quickly settling into the art deco aesthetic, led by Harry Weedon’s architectural office and often to designs of Cecil Clavering.

Eyles’ talk was preceded by a fine, short documentary Odeon Cavalcade (which British readers can currently view for free HERE on the BFI Player) in which the architects featured prominently, discussing their approaches, failures and success across the projects, and the sheer scale of Odeon and its architecture had upon British cities and cinema, and it all started from a Birmingham suburb.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figs.ii-iv

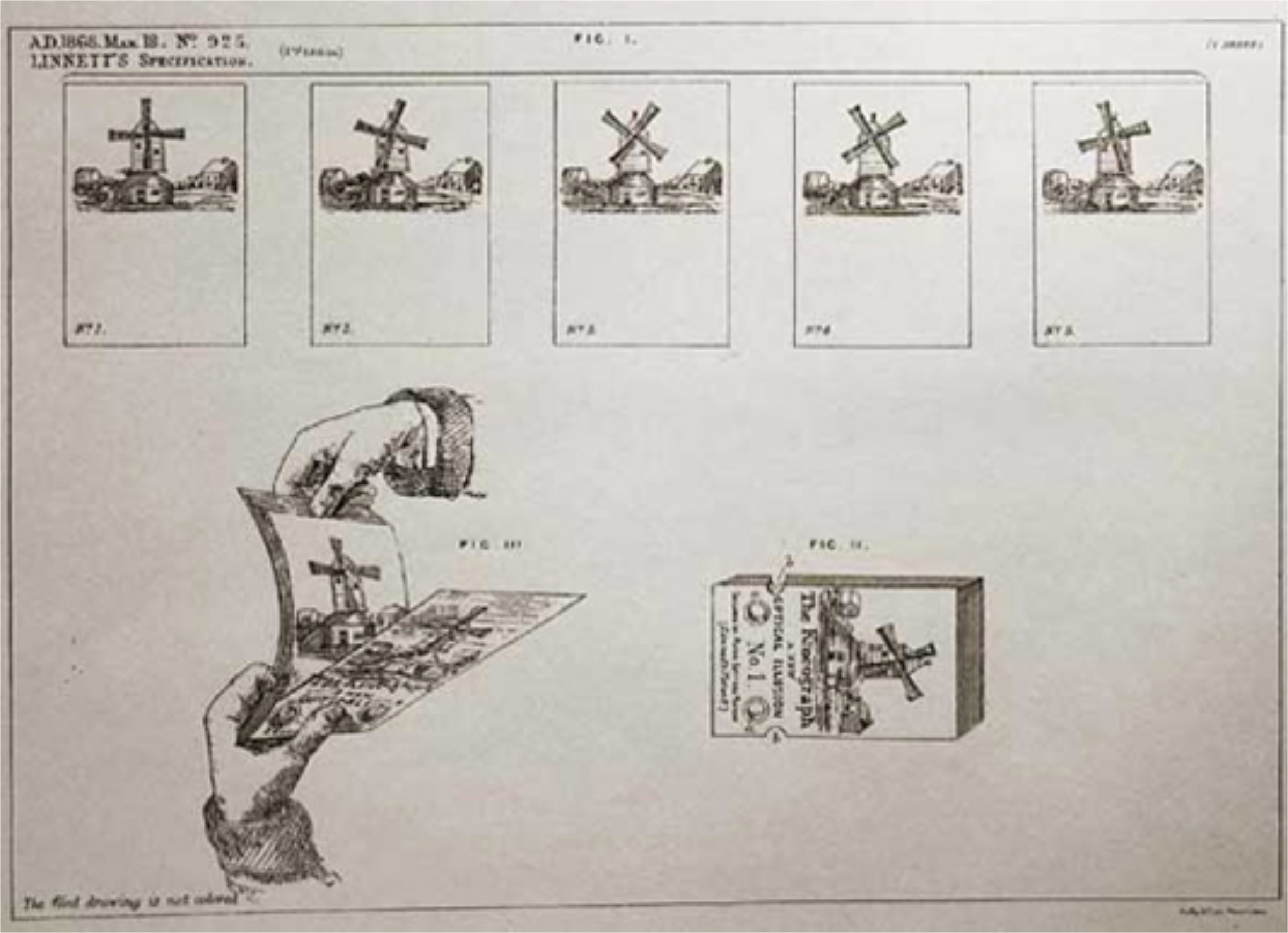

But, you would be missing a lot if you presumed that was all Birmingham had to say about the history of cinema, and the Wonderland exhibition sets out, in a packed gallery space, to tell the story of film in the city using artefacts, memorabilia, and imagery recording everything from the pre-cinema moving image in the city – Birmingham printer John Barnes Linnett patented the Kineograph flipbook – through to 21st century pop-up screenings and event cinema led by and for the city’s various ethnic and cultural communities.

![]()

![]()

A video screen shows silent footage from 1901 of workers leaving the gates of a Smethwick engineering works, shot by famed cinematographers Mitchell and Kenyon (again available for some readers on the BFI Player HERE) which local showman Waller Jeffs, one of the city’s first to show moving pictures in theatres, would have presented to the public.

Also exhibited are artworks from the Birmingham Museum collection, including of Jeffs own cinema, the Villa Cross Picture House with its stained-glass rose window glowing into the street, and a number of archive photographs showing Birmingham’s cinemas across an array of architectural styles, each impressive, civic and a space of escape and pleasure, but over the years largely lost to development or abandonment.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Reminding that the film is about excitement and the imaginary and not about the loss of the once-proud cinema architecture, moments of fun and play punctuate the exhibition. In particular, a display of a film and macro-photographs documenting a sublimely detailed model of Odeon New Street by Cyril Barbier is a joy. It was the cinema where Barbier went to see Casablanca with a girl called Norah, who he would later go on to marry – the scale model is his memory of that night, a memory he lovingly excavated over the 28 years it took him to build.

![]()

![]()

Around the space, various lost cinemas are presented, and not just the city’s Odeons: The Beaufort was built in 1929, a mock Tudor mansion, demolished in 1979 with the stained glass shipped to America; 1928’s Alhambra was the first ‘atmospheric’ cinema outside of the capital, designed to whisk visitors into another place and time once crossing the threshold; and the geometry of 1956’s The Cinephone (shown below in Pathe footage) which within a few years became reliant on sex films to sustain its operations.

Fig.xv

The exhibition concludes with how cinema has been a force in the city for communities and cultures, whether cult kung fu films of the early 1980s, film as a vital tool for the South Asian community to coalesce around, or how pop-up screenings have brought Caribbean cinema to a new, young audience. For Flatpack Festival the theme left the gallery space and filled the city with over 65 film-themed talks, screenings, club nights, and comedy events, director Ian Francis saying:

“We've also got a team of 25 volunteers from all across the city who have their own personal interests to research and share whether it's kung fu movies, cinema upholstery, or the South Asian story. All this combined with the design of the space will make for a unique experience to look back and also reflect on the future."

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figs.xvi-ixx

Curated by Flatpack Festival, an annual two-week long celebration of all things moving image, the exhibition Wonderland finds a local perspective on a global artform, but which speaks wider than the M5, M6, and M42 bounding the city, and into social and architectural realms.

The initial hook for the story of film in Birmingham is Odeon, the now-international cinema chain which was born from the Midlands city from the 1930s and became synonymous with the mass-growth of the artform in the modern age, suitably using deco Moderne as an architectural language. The company was formed by Oscar Deutsch, bored by the metal industry which had given him money but not intellectual curiosity, and as a film-fan set out to make cinemagoing a whole new experience for a generation and beyond.

Fig.i

Deutsch, born in the Balsall Heath area of the city in 1895, began his cinema career in 1925, renting three Midlands cinemas as a business interest, before shortly after opening his first in Dudley in 1928. In less than a decade the Odeon chain (the idea that the name is an acronym of Oscar Deutsch Entertains Our Nation is an urban myth) grew to over 250 cinemas across the country, opening three brand-new cinemas a week at the peak.

As part of the festival there was a talk historian Allen Eyles who took the audience through the changing architectural language of many of those cinema buildings, from initial middle-English and Moorish typologies and then quickly settling into the art deco aesthetic, led by Harry Weedon’s architectural office and often to designs of Cecil Clavering.

Eyles’ talk was preceded by a fine, short documentary Odeon Cavalcade (which British readers can currently view for free HERE on the BFI Player) in which the architects featured prominently, discussing their approaches, failures and success across the projects, and the sheer scale of Odeon and its architecture had upon British cities and cinema, and it all started from a Birmingham suburb.

Figs.ii-iv

But, you would be missing a lot if you presumed that was all Birmingham had to say about the history of cinema, and the Wonderland exhibition sets out, in a packed gallery space, to tell the story of film in the city using artefacts, memorabilia, and imagery recording everything from the pre-cinema moving image in the city – Birmingham printer John Barnes Linnett patented the Kineograph flipbook – through to 21st century pop-up screenings and event cinema led by and for the city’s various ethnic and cultural communities.

Figs.v,vi

A video screen shows silent footage from 1901 of workers leaving the gates of a Smethwick engineering works, shot by famed cinematographers Mitchell and Kenyon (again available for some readers on the BFI Player HERE) which local showman Waller Jeffs, one of the city’s first to show moving pictures in theatres, would have presented to the public.

Also exhibited are artworks from the Birmingham Museum collection, including of Jeffs own cinema, the Villa Cross Picture House with its stained-glass rose window glowing into the street, and a number of archive photographs showing Birmingham’s cinemas across an array of architectural styles, each impressive, civic and a space of escape and pleasure, but over the years largely lost to development or abandonment.

Figs.vii-xii

Reminding that the film is about excitement and the imaginary and not about the loss of the once-proud cinema architecture, moments of fun and play punctuate the exhibition. In particular, a display of a film and macro-photographs documenting a sublimely detailed model of Odeon New Street by Cyril Barbier is a joy. It was the cinema where Barbier went to see Casablanca with a girl called Norah, who he would later go on to marry – the scale model is his memory of that night, a memory he lovingly excavated over the 28 years it took him to build.

Figs.xiii,xiv

Around the space, various lost cinemas are presented, and not just the city’s Odeons: The Beaufort was built in 1929, a mock Tudor mansion, demolished in 1979 with the stained glass shipped to America; 1928’s Alhambra was the first ‘atmospheric’ cinema outside of the capital, designed to whisk visitors into another place and time once crossing the threshold; and the geometry of 1956’s The Cinephone (shown below in Pathe footage) which within a few years became reliant on sex films to sustain its operations.

Fig.xv

The exhibition concludes with how cinema has been a force in the city for communities and cultures, whether cult kung fu films of the early 1980s, film as a vital tool for the South Asian community to coalesce around, or how pop-up screenings have brought Caribbean cinema to a new, young audience. For Flatpack Festival the theme left the gallery space and filled the city with over 65 film-themed talks, screenings, club nights, and comedy events, director Ian Francis saying:

“We've also got a team of 25 volunteers from all across the city who have their own personal interests to research and share whether it's kung fu movies, cinema upholstery, or the South Asian story. All this combined with the design of the space will make for a unique experience to look back and also reflect on the future."

Figs.xvi-ixx

Flatpack Festival is produced by Birmingham-based charitable organisation Flatpack Projects, a mobile arts organisation that shows amazing work, brings people together and develops new ideas. Since 2006, the festival (which began life as a monthly mixed-media night at the Rainbow pub in Digbeth) has shown over 3,000 films to over 100,000 people and is a vital fixture in Birmingham’s cultural calendar. Stirring together a colourful stew of screenings and performances, walks and installations, the Flatpack programme boasts a mind-boggling range of international talent with an emphasis on the playful, surprising and indefinable. Flatpack Festival is funded by the National Lottery via Arts Council England and the British Film Institute.

www.flatpackfestival.org.uk

The Birmingham 2022 Festival unites people from around the Commonwealth through a celebration of creativity, in a six-month long programme, shining a spotlight on the West Midland’s culture sector.

Running from March to beyond the conclusion of the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games in September, the festival aims to entertain and engage over 2.5 million people in person and online. Delivering over 200 projects across the region including art, photography, dance, theatre, digital art and more the festival will embrace local culture and generate lasting change and a creative legacy beyond the games with funding to community led projects from Birmingham City Council’s Creative City Grants scheme.

www.birmingham2022.com/festival

Birmingham Museums Trust is an independent charity formed in 2012 that manages the city’s museum collection and venues on behalf of Birmingham City Council. It uses the collection of around 1 million objects to provide a wide range of arts, cultural and historical experiences, events and activities that deliver accessible learning, creativity and enjoyment for citizens and visitors to the city. The collection reflects the city’s historic and continuing position as a major international centre for manufacturing, commerce, education and culture. Most areas of the collection are designated as being of national importance, including the finest public collection of Pre-Raphaelite art in the world. Attracting over one million visits a year, Birmingham Museums venues are Aston Hall, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Blakesley Hall, Museum Collection Centre, Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, Sarehole Mill, Soho House, Thinktank and Weoley Castle.

www.birminghammuseums.org.uk

www.birmingham2022.com/festival

Birmingham Museums Trust is an independent charity formed in 2012 that manages the city’s museum collection and venues on behalf of Birmingham City Council. It uses the collection of around 1 million objects to provide a wide range of arts, cultural and historical experiences, events and activities that deliver accessible learning, creativity and enjoyment for citizens and visitors to the city. The collection reflects the city’s historic and continuing position as a major international centre for manufacturing, commerce, education and culture. Most areas of the collection are designated as being of national importance, including the finest public collection of Pre-Raphaelite art in the world. Attracting over one million visits a year, Birmingham Museums venues are Aston Hall, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Blakesley Hall, Museum Collection Centre, Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, Sarehole Mill, Soho House, Thinktank and Weoley Castle.

www.birminghammuseums.org.uk

visit

Wonderland runs through to 30 October 2022 at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

www.birminghammuseums.org.uk/bmag/whats-on/wonderland-birmingham-s-cinema-stories

www.flatpackfestival.org.uk/projects/wonderland

images

fig.i Wonderland exhibition. Photo

© Jas Sansi

fig.ii Odeon cinema, Sutton Coldfield.

Photo © Tony Hisgett. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odeon_Cinema_Sutton_Coldfield.jpg

fig.iii

Odeon cinema, Dudley. Photo © Tony Hisgett. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Former_Odeon_Cinema_Dudley_%285512243302%29.jpg

fig.iv

Odeon cinema, Kingstanding. Photo © Tony Hisgett. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odeon_Cinema_Kingstanding_%281%29.jpg

fig.v Still image from Employees leaving the Tangye Engineering Works, Smethwick, 1901. From the Mitchell and Kenyon Collection, viewable at: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-employees-leaving-tangyes-engineering-works-smethwick-1901-1901-online

fig.vi John Barnes Linnett’s patent for the Kineograph. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kineograph_patent.svg

fig.vii

Wonderland exhibition. Photo© Jas Sansi

fig.viii Newtown Palace cinema, Courtesy Flatpack Cinema

fig.ix Tatler News Theatre, Courtesy John Neville Cohen

fig.x Imperial Cinema (1980), Courtesy Flatpack Cinema

fig.xi Aston Cross cinema,

© Jean Turley

fig.xii

Warwick Bowl, © Jean Turley

figs.xiii, xiv Photographs of Cyril Barbier’s model of Odeon New Street. © David Rowan

fig.xv New Cinephone opened, Birmingham (1956),

©

British Pathé. Available at: https://youtu.be/53DMdn6HRBA

fig.xvi Foyer of Newtown Palace (1965), Courtesy Flatpack Cinema

fig.xvii

Wonderland exhibition. Photo© Jas Sansi

fig.xviii

Auditorium of Newtown Palace (1965), Courtesy Flatpack Cinema

fig.xix

Bobby poster, Courtesy Flatpack Cinema

publication date

21 June 2022

tags

Cyril Barbier, John

Barnes Linnett, Birmingham, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, BMAG, British Film Institute, BFI, Cinema, Cecil Clavering, Oscar Deutsch, Allen

Eyles, Film, Flatpack Festival, Ian Francis,Waller Jeffs, Modernism, Odeon, Mitchell and Kenyon, Harry Weedon, Wonderland

www.birminghammuseums.org.uk/bmag/whats-on/wonderland-birmingham-s-cinema-stories

www.flatpackfestival.org.uk/projects/wonderland