Lives in landscapes: Chris Killip’s photography

With a retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery in London, the work of Chris Killip, who passed two years ago, is celebrated & reconsidered. Lewis Bush looks at how Killip captured lives of individuals & communities in the landscapes they made & wonders how that reflects on today’s politics.

The photographer Chris Killip, who died in 2020, made some of his most significant work in the north-east of England during a period of dramatic change and as long-standing heavy industries, around which entire communities had grown, began to be dismantled.

These were battles, sometimes literally, but certainly metaphorically for the future of the United Kingdom, and as Zhou Enlai supposedly said of the French revolution,[i] even forty years later it is too early to judge the outcome of many of these clashes of class, region, and ideology. Killip’s take on this period for change was hard to miss, reflected in the title of the book which he is best known for, In Flangrante, a compression of an archaic Latin legal term for the catching of a crime in the very act of being committed.

figs.i,ii

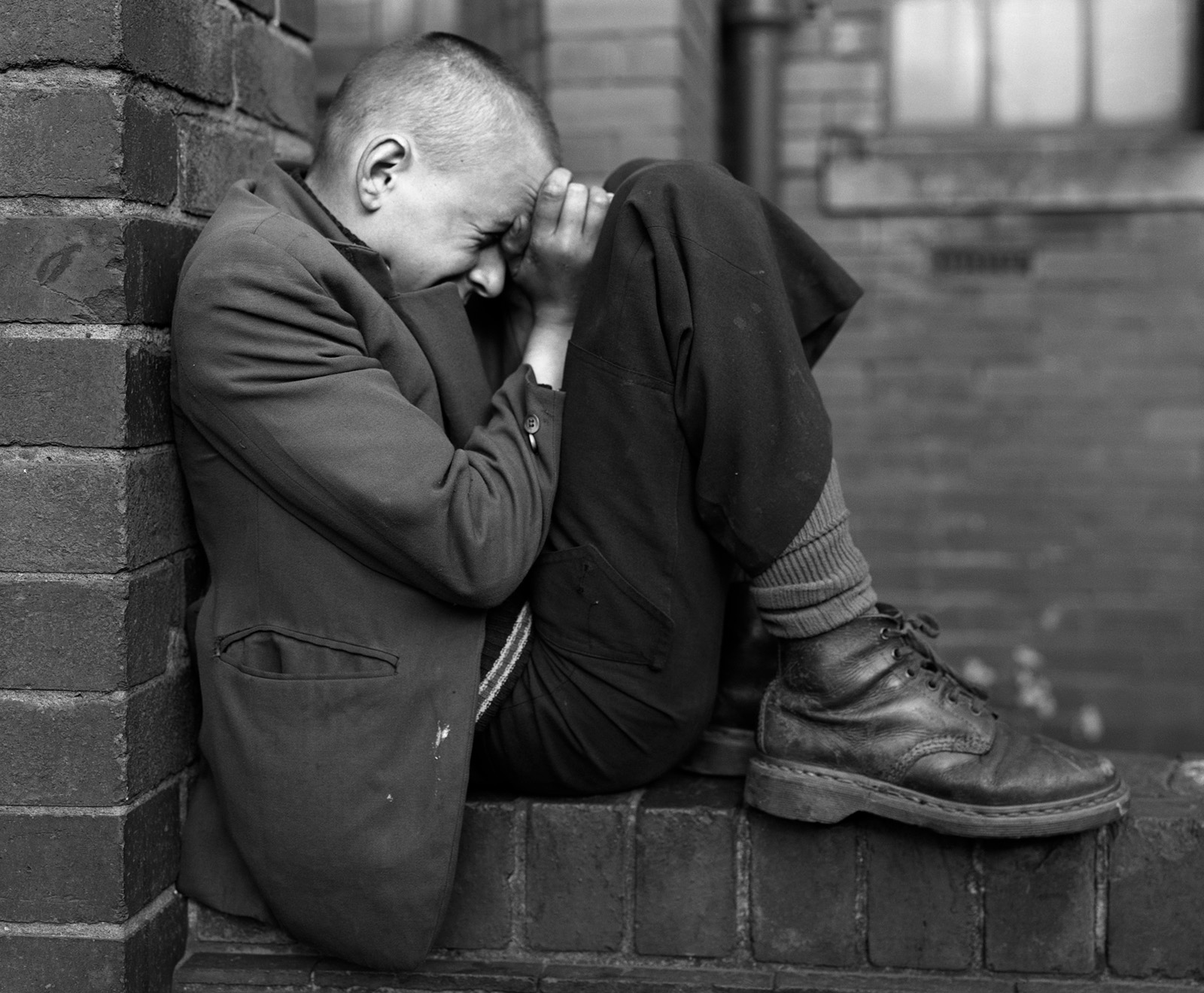

But Killip’s work itself is anything but flagrant or conspicuous, instead it is shot through with a subtlety that rewards careful consideration and much time spent with his photographs. In particular his relationship with place and spaces seems to have been ever shifting and difficult to quantify. One of the recurrent themes in many of his projects is the idea of people surviving, not because of the spaces they live in, but almost in spite of them, against them, kept going instead by the strength of the communities of which they are a part, communities which Killip in turn often became a part of.

For example, his work in the village of Skinningrove, focused on a group of young fishermen, modishly dressed as punks at the same time as they work on the boats and on the sometimes-unforgiving seas. One of the men later drowned, with Killip compiling an album of his photographs for the mourning family.

figs.iii,iv

Likewise, his series on Northumberland sea coalers, a community scraping a living from coal spoil washed ashore from a nearby mine, is almost medieval in its depiction of their lives. At the same time the relationship between the sea coalers and the importance of this community in sustaining them on the inhospitable place they called home is ever present in Killip’s photographs.

Indeed this closeness both nearly prevented Killip’s photographs from being made, and then made his access possible. Distrustful of outsiders, Killip was repeatedly run off the beach, until a chance encounter with a key figure in the community led to him being eventually accepted, he later went on to live like the sea coalers, in a caravan on the desolate beach.

figs.v,vi

One of the other things that emerges in Killip’s work is the juxtaposition of everyday life lived up against the grim machinery and events of a Britain in decline. A scrawny playground sits at the base of a power plant’s cooling tower. People trudge wearily across wasteland overshadowed by advertising hoardings. A group of children stand on a wall with a vast, partially burnt-out housing estate behind them BOBBY SANDS GREEDY IRISH PIG graffitied on one corner. The people in many of Killip’s photographs look not at home in their environments, but more inured to them.

Killip almost always lived in each place he photographed, in contrast to some documentary photographers who might spend protracted periods in an area, but seldom were so immersed in their daily life. This difference again becomes evident in the reappearance of the same locations across spans of time. One particularly striking example being a street in Tyneside, first photographed populated by people and children, later resembling an abandoned wasteland of half demolished buildings, as if in the aftermath of a war.

Although much will be familiar in this exhibition to those acquainted with his work, there may still be some nice surprises in the form of less seldom shown pieces. This includes an extensive display of work from his island home, photographs which often gets subordinated to his better-known later work in the north of England. Perhaps because it was made so early in his career, the influence of American modernists like Paul Strand and Walker Evans is far clearer to see in photographs, many of which linger on the sparse domestic spaces of the islanders.

figs.vii,viii

In contrast in Killip’s later, more mature works it is noticeable that his photographs are almost never unpeopled, a reflection perhaps of his fundamental, generous interest in them.[ii] It is this interest, which I suspect is what made his photographs special at the time they were made, and arguably so important again now.

It was clearly not planned by the curators (after all who can make any plans with British politics what they are right now), but it is hard to miss the significance of this exhibition opening during the extremely brief tenure of a British Prime Minister who directly positioned herself as an heir to Margaret Thatcher, even at the same time as so self-evidently lacking Thatcher’s considerable (if controversial) political talents. In a country which prides itself on its values, but where human life is often traded too cheaply, Killip’s photographs help to remind us of what was, and what is, at stake.

[1] Enlai is supposed to have thought the

question was about the recent 1968 political protests. As the interpreter present later said it was “a misunderstanding that was too delicious to invite

correction”.

[2] It speaks volumes that some of his students

at Harvard’s VES (a sort of strange hybrid department seeming to combine all the subjects that Harvard isn’t sure what to do with) wore Chairman Mao style badges with Killip’s face on them as a sort of bizarre tribute to him.

Lewis Bush is a researcher, writer & photographer working across media & platforms to visualise the workings of powerful agents, organisations & practices. He has exhibited, published & taught internationally.

www.lewisbush.com

Chris Killip was born in Douglas, Isle of Man in 1946, Chris Killip left school at age sixteen and joined the only four star hotel on the Isle of Man as a trainee hotel manager. In June 1964 he decided to pursue photography full time. He worked as a freelance assistant for various photographers in London from 1966-69. In 1969, after seeing his very first exhibition of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he decided to return to photograph in the Isle of Man. In 1972 he received a commission from The Arts Council of Great Britain to photograph Huddersfield and Bury St Edmunds for the exhibition ‘Two Views — Two Cities’. In 1975, he moved to live in Newcastle-upon-Tyne on a two year fellowship as the Northern Arts Photography Fellow. He was a founding member, exhibition curator and advisor of Side Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, as well as its director, from 1977-79. In 1989 he received the Henri Cartier Bresson Award and in 1991 was invited to be a Visiting Lecturer at the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, Harvard University. In 1994 he was made a tenured professor and was department chair from 1994-98. He retired from Harvard in December 2017 and died in 2020. His work is featured in the permanent collections of major institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; George Eastman House; Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco; Museum Folkwang, Essen; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

www.chriskillip.com

www.chriskillip.com

visit

Chris Killip, retrospective is on at The Photographers’ Gallery until February 19 2023. Full information available at:

www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/chris-killip-retrospective

images

fig.i Bever, Skinningrove, N. Yorkshire, 1983

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos.

fig.ii Family on a Sunday walk, Skinningrove , 1982

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

fig.iii Helen and her Hula

hoop, Seacoal Camp, Lynemouth, Northumbria, 1984

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

fig.iv Unidentified man and Brian

Laidler , Seacoal Beach, Lynemouth, January, 1984

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

fig.v ‘Boo’ on a horse,

Seacoal Camp, Lynemouth, Northumbria, 1984 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

fig.vi Cookie in the snow,

Seacoal Camp, Lynemouth, Northumbria, 1984 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

fig.vii Girls Playing in the street, Wallsend, Tyneside,1976 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

fig.viii Youth on wall, Jarrow, Tyneside, 1975 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum

Photos

publication date

08 November 2022

tags

1980s, Lewis Bush, Community, Conservatives, Walker Evans, Chris Killip, Landscape, Northumberland, The Photographers Gallery, Photography, Politics, Skinningrove, Paul Strand, Margaret Thatcher, Tyneside, Wallsend

www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/chris-killip-retrospective