Power & photography: picturing architecture in the 19th century

An exhibition in Oxford explores the earliest days of photography. Curated by Geoffrey Batchen, A New Power: Photography in Britain 1800-1850 catalogues how photography overlapped with more traditional mediums, with Josh Allen pulling focus on how the emergent technology was used to capture architecture.

A New Power:

Photography in Britain 1800–1850 is one of a duo of exhibitions at the

University of Oxford’s Weston Library tracing and interpreting the origins of

photography as a medium. Aptly named, it questions the nature of power in early-

to mid-19th Century Britain, emerge from every object on display and the

exhibition as a whole.

Curated by historian of photography Geoffrey Batchen, the story developed is one of photography’s top-down emergence prior to its wider diffusion throughout society. The exhibition explores the scientific, business, and industrial imperatives which spurred the technical advances leading to the medium’s development, before going on to consider the ways in which photography was embraced by the powerful to further commercial, political, and imperial goals.

![]()

fig.i

Architecture looms large in this story. Monuments, buildings,

and townscapes were popular subjects for early daguerreotypes and calotypes,

while within a few years of the first truly successful photographs in 1839 and

1840, pictures showcasing architecture had moved from scientific experiment and

sideshow curiosity to playing a significant role in advancing commercial

opportunities and projecting power. Here the exhibition teases out and

foregrounds early Victorian modernisation – for better and for worse – in ways

that focus attention on developments in more recent times.

![]()

The printing technology available during photography’s early years was unable to copy the period’s photographs precisely. By its nature, Louis Daguerre’s eponymous process produced unique objects while Henry Fox-Talbot’s calotypes were too faint and indistinct to readily copy en masse. This lead to editors, entrepreneurs, and publicists of all varieties deploying the new processes to capturing reality only as a means of forming a primary image for the existing cadre of artists skilled in creating engravings for print to trace over.

This means that in many of the images exhibited, the photographs themselves are absent and we see only prints from the post-photograph engravings. We see incredibly finely detailed cityscapes of early 1840s London, vivid renditions of newly built factories, civic buildings, and the Great Exhibition of 1851. However, while the etchings created by skilled craft workers remain, in most cases the original photographs were destroyed during the process of creating the printing plates or once the print was sufficient, were not retained.

![]()

The commercial potential of early photographic images and the reasons they rapidly became important – despite their technological limitations – is encapsulated in a tiny, spectral daguerreotype of the Duke of Wellington made shortly before his death in 1852. The image itself is only a few inches in diameter and is now incredibly faint 170 years after its creation. In the exhibition cabinet it is surrounded by nine derivative works, created by artists and copyists with varying degrees of licence, who likely never clapped eyes on the Duke himself, and whose work was enabled by their ability to use the photograph as model. The exhibition text notes that access to the photograph for copying became incredibly lucrative during the clamour for saleable pictures of the hero of Waterloo immediately after his death.

![]()

What the spectral presence of a photograph underlying these copied images points towards is the ways in which new and existing technologies coexist – at least for a time. There is seldom a clean break and indeed new processes can breathe new life into old techniques by increasing the speed at which they can be undertaken and mediated, and the fidelity they can achieve.

As well as the spectral photographs underlying many of the engravings that proliferated in publications during the 1840s and 1850s surviving street and architectural photographs from the time appear eerily empty. The long exposure times needed to capture the images meant any living creature working outdoors, or just wandering into frame, were erased. Early camera technology and photographic processes could not capture their movements.

![]()

To paraphrase Allan Sekula, who wrote about Ebenezer Landellis’ London Taken From the Summit of the Duke of York’s Column 1842 the effect is to erase people and their labour. Sekula’s contention being that for the early commissioners and consumers of photographs this invisibilisation of labour and day-to-day life was in fact desirable, meaning they could enjoy an uncluttered view of the real estate.

This said, one of the functions of the ghostly engravers who worked from photographic images so they could be printed, published, and sold to the public, could be to return life and movement back into the renderings. Whether this was imagined street porters running errands, carters transporting bulk loads, or sailors in quick tiny lighters servicing sea going vessels in vast harbours.

![]()

The exhibition concludes that photography’s rapid integration into the circuits of commercial, capital accumulation and political power in the mid-19th Century Britain culminated at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and in the process celebrating Joseph Paxton’s sunlit Crystal Palace and giving it powerful significance. When Instagram emerged over a decade ago, made possible by the smartphone-supported networked communications nexus, it became fashionable to talk about new buildings and other forms of architecture having been created to be Instagrammable, implicitly suggesting that they were a form of capitalist froth.

By contrast, histories of the Great Exhibition – whilst accepting that it was intended as a spectacle – typically interpret the building as a symbol of Great Britain's industrial might and technological prowess, with imagery of it an extension of that power. An additional reading is that just as we might feel contemporary architecture intentionally provides a backdrop for quick networked photography, the Crystal Palace’s design benefited the photographic slower communications technology of its day: its vast expanses of glass enabled the light dependent daguerreotypists of the London Illustrated News and other publications to document the Great Exhibition and show this ostentatiously massive spectacle of commerce to a wide audience.

Such photographs of the Great Exhibition and its vitrine, the Crystal Palace, live spectrally in beautifully traced and embellished form across pages of surviving publications. With whatever degree of intention within a decade of being born, photography was closely intertwined with architecture, the representation of architecture, and power emanating from it – forming questions related to representations of the built environment we still grapple with today.

![]()

Curated by historian of photography Geoffrey Batchen, the story developed is one of photography’s top-down emergence prior to its wider diffusion throughout society. The exhibition explores the scientific, business, and industrial imperatives which spurred the technical advances leading to the medium’s development, before going on to consider the ways in which photography was embraced by the powerful to further commercial, political, and imperial goals.

fig.i

fig.ii

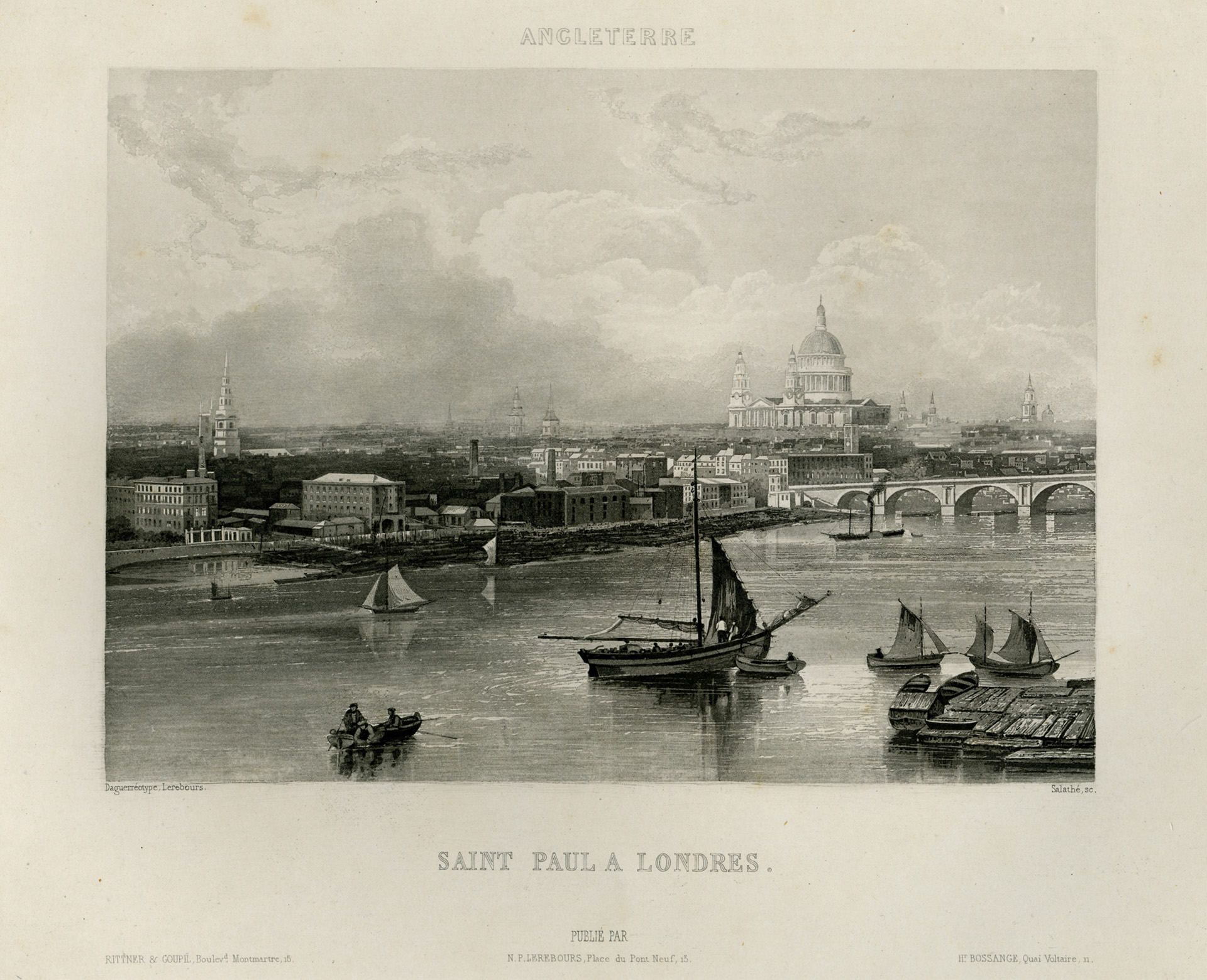

The printing technology available during photography’s early years was unable to copy the period’s photographs precisely. By its nature, Louis Daguerre’s eponymous process produced unique objects while Henry Fox-Talbot’s calotypes were too faint and indistinct to readily copy en masse. This lead to editors, entrepreneurs, and publicists of all varieties deploying the new processes to capturing reality only as a means of forming a primary image for the existing cadre of artists skilled in creating engravings for print to trace over.

This means that in many of the images exhibited, the photographs themselves are absent and we see only prints from the post-photograph engravings. We see incredibly finely detailed cityscapes of early 1840s London, vivid renditions of newly built factories, civic buildings, and the Great Exhibition of 1851. However, while the etchings created by skilled craft workers remain, in most cases the original photographs were destroyed during the process of creating the printing plates or once the print was sufficient, were not retained.

fig.iii

The commercial potential of early photographic images and the reasons they rapidly became important – despite their technological limitations – is encapsulated in a tiny, spectral daguerreotype of the Duke of Wellington made shortly before his death in 1852. The image itself is only a few inches in diameter and is now incredibly faint 170 years after its creation. In the exhibition cabinet it is surrounded by nine derivative works, created by artists and copyists with varying degrees of licence, who likely never clapped eyes on the Duke himself, and whose work was enabled by their ability to use the photograph as model. The exhibition text notes that access to the photograph for copying became incredibly lucrative during the clamour for saleable pictures of the hero of Waterloo immediately after his death.

fig.iv

What the spectral presence of a photograph underlying these copied images points towards is the ways in which new and existing technologies coexist – at least for a time. There is seldom a clean break and indeed new processes can breathe new life into old techniques by increasing the speed at which they can be undertaken and mediated, and the fidelity they can achieve.

As well as the spectral photographs underlying many of the engravings that proliferated in publications during the 1840s and 1850s surviving street and architectural photographs from the time appear eerily empty. The long exposure times needed to capture the images meant any living creature working outdoors, or just wandering into frame, were erased. Early camera technology and photographic processes could not capture their movements.

fig.v

To paraphrase Allan Sekula, who wrote about Ebenezer Landellis’ London Taken From the Summit of the Duke of York’s Column 1842 the effect is to erase people and their labour. Sekula’s contention being that for the early commissioners and consumers of photographs this invisibilisation of labour and day-to-day life was in fact desirable, meaning they could enjoy an uncluttered view of the real estate.

This said, one of the functions of the ghostly engravers who worked from photographic images so they could be printed, published, and sold to the public, could be to return life and movement back into the renderings. Whether this was imagined street porters running errands, carters transporting bulk loads, or sailors in quick tiny lighters servicing sea going vessels in vast harbours.

fig.vi

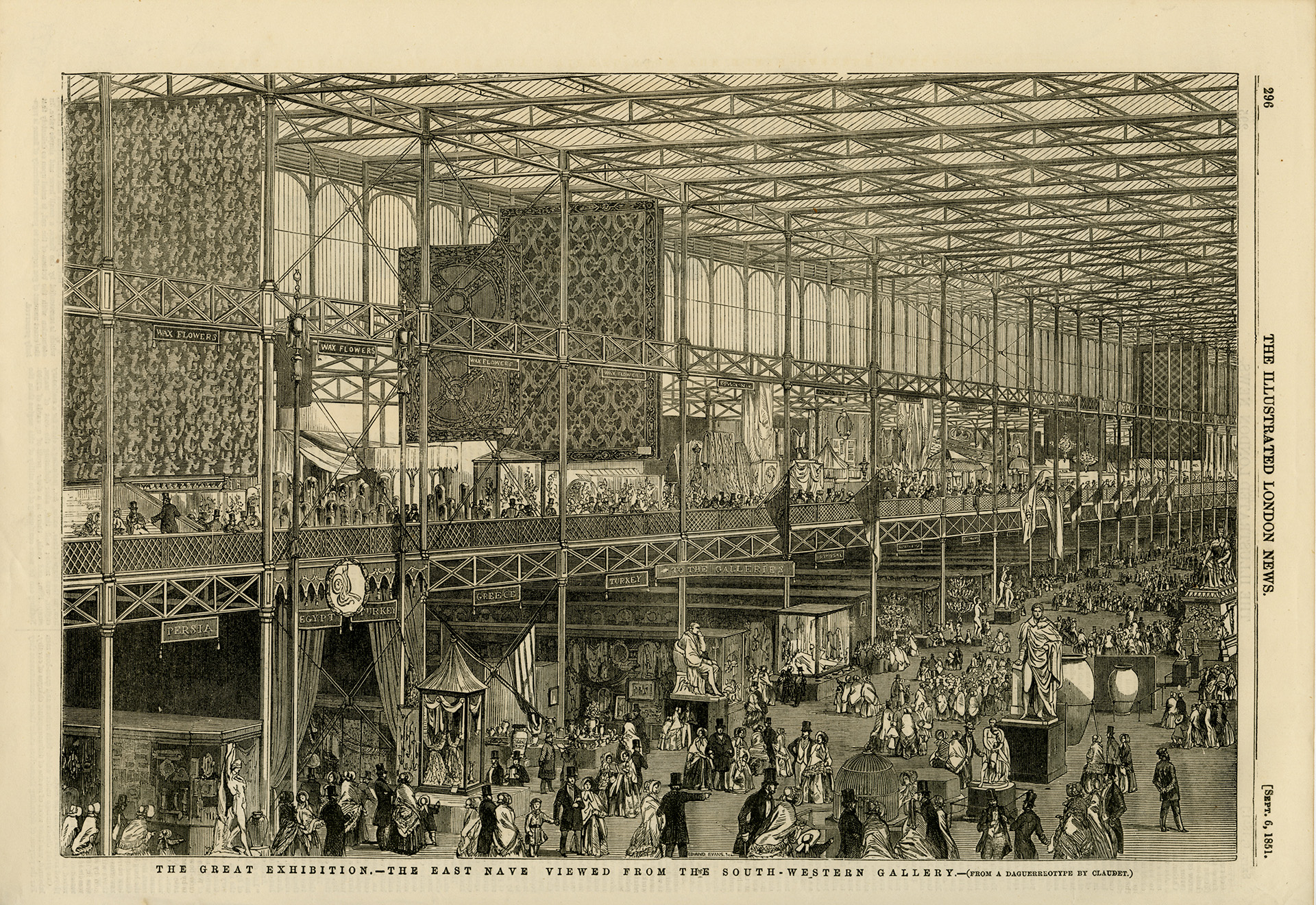

The exhibition concludes that photography’s rapid integration into the circuits of commercial, capital accumulation and political power in the mid-19th Century Britain culminated at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and in the process celebrating Joseph Paxton’s sunlit Crystal Palace and giving it powerful significance. When Instagram emerged over a decade ago, made possible by the smartphone-supported networked communications nexus, it became fashionable to talk about new buildings and other forms of architecture having been created to be Instagrammable, implicitly suggesting that they were a form of capitalist froth.

By contrast, histories of the Great Exhibition – whilst accepting that it was intended as a spectacle – typically interpret the building as a symbol of Great Britain's industrial might and technological prowess, with imagery of it an extension of that power. An additional reading is that just as we might feel contemporary architecture intentionally provides a backdrop for quick networked photography, the Crystal Palace’s design benefited the photographic slower communications technology of its day: its vast expanses of glass enabled the light dependent daguerreotypists of the London Illustrated News and other publications to document the Great Exhibition and show this ostentatiously massive spectacle of commerce to a wide audience.

Such photographs of the Great Exhibition and its vitrine, the Crystal Palace, live spectrally in beautifully traced and embellished form across pages of surviving publications. With whatever degree of intention within a decade of being born, photography was closely intertwined with architecture, the representation of architecture, and power emanating from it – forming questions related to representations of the built environment we still grapple with today.

fig.vii

Josh Allen is a

contemporary historian, writer, journalist & and occasional curator from

Birmingham. His practice focuses upon place, working class histories, popular

understandings of the past with a particular interest in photography,

landscapes, the built environment & walking.

www.linktr.ee/josh_allen

images

A New Power: Photography in Britain, 1800-1850, curated by Geoffrey Batchen, is a free exhibition at the Weston Library, Oxford, alongside a second exhibition Bright Sparks: Photography and the Talbot Archive celebrating the Bodleian Libraries' acquisition of the archive of the British inventor of photography, William Henry Fox Talbot, and the legacy of his life and work.

Further information at:

www.visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/event/a-new-power

images

fig.i

Laman Blanchard ed., ‘Photographic Phenomena,’ George Cruikshank’s Omnibus, London: Tilt and Bourge, 1842). Courtesy of a Private Collection.

fig.ii

Unknown engraver (England), Portrait of Henry Mayhew after a Daguerrotype by Beard, circa 1851. From Henry Meyhew’s “London Labour and the London Poor”.

fig.iii

Noël Marie Paymal Lerebours (France), Excursions daguerrienes, vues et monuments les plus remarquables du globe (Volume one, Paris, Rittner, Goupil, 1840-1842) plate 4, Angleterre, Saint Paul a Londres, c. 1840.

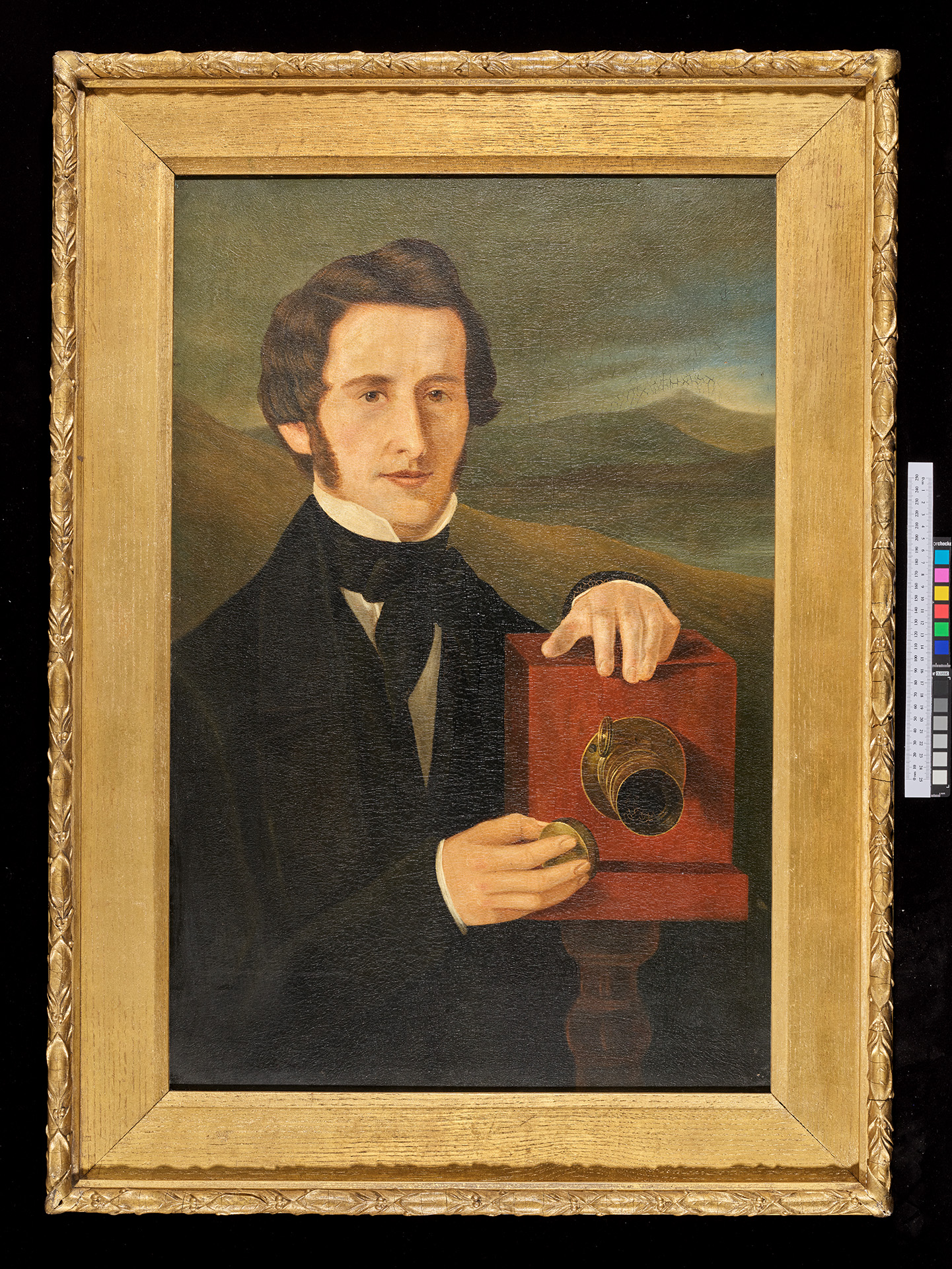

fig.iv Artist Unknown, Portrait of a man (resembling Jabez Hogg) operating a daguerreotype camera, c. 1845. Credit - The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. This painting was acquired by the Bodleian Libraries at an auction and is the only known painting of a daguerreotypist at work. The man bears a strong resemblance to the

photographer (and later ophthalmic surgeon) Jabez Hogg, who in 1843 published a 'Manual of Photography’ and worked at the Illustrated London News from 1850 to 1866.

fig.v

Ebenezer Landells et. al. (engraver), London in 1842, taken from the summit of the Duke of York’s Column. Illustrated London News, 30 July 1842. Credit Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

fig.vi Studio of Richard Beard Jr. (London), Tyrolese Singers, 1851-52. Credit - Royal Collection Trust © His Majesty King Charles III 2022.

This daguerreotype, produced and enamelled by the studio of Richard Beard, was purchased by Queen Victoria in 18522, the same year in which her mother, the Duchess of

Kent, arranged for the Tyrolese minstrels to surprise the Queen with a serenade at breakfast for her birthday at Osborne. About the event, the Duchess wrote: “Victoria appeared very much pleased with the surprise”.

fig.vii Engravers unknown (England), The Great Exhibition: The east nave, viewed from the south-western gallery, 1851, from Illustrated London News, 6 September 1851, p. 296. Courtesy of a Private Collection.

Held at Crystal Palace in London in 1851, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations was one of the most influential cultural events of the 19th century and the Illustrated London New did not fail to record its scale and significance using an equally influential invention that would shape the current century and those to come.

publication date

29 March 2023

tags

Josh Allen, Geoffrey Batchen, Bodleian Library, Calotype, Crystal

Palace, Louis Daguerre, Daguerreotype, Henry Fox-Talbot, Great Exhibition, Instagram,Ebenezer Landellis, Henry Mayhew, Joseph Paxton, Photography, Power, Printing, Allan

Sekula, Technology, Victorian, Weston Library

Further information at:

www.visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/event/a-new-power