Drawing a line from past to future: Norman Foster at Centre Pompidou

The main gallery at the Centre Pompidou is for the first time given over to a retrospective of an architect. In an exhibition spanning design from the 1950s to the near future, the work of Norman Foster is explored through drawings, models & assorted art & engineering objects. But, throughout, it is the simple pencil which is most present.

A vast new exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, offers

a career-spanning retrospective of architect Norman Foster. From 1950s student

projects from his time at the University of Manchester School of Architecture

right through to futuristic plans for architecture on Mars, the thematic

exhibition is the largest at the museum dedicated to an architect, offering up the

open-plan expanse of its top-floor Gallery 1, with views across the French capital.

The main exhibition is a rich agglomeration of drawings, models of Foster’s architecture, alongside assorted artworks and engineering which have inspired him. But before the visitor encounters this deeply curated collection, an anteroom packed with drawings, slide photographs, and sketchbooks sets the scene for the architect’s creative approach.

It is a fascinating entrance to the exhibition, rich in approaches to representing imagination, with an eye and style which can be tracked across seven decades of drawing. The exhibition’s curator, Frédéric Migayrou, tells recessed.space that this room is designed “to penetrate the spirit, to get inside the head of the architect.” In reality, we get into the head of many architects: Foster as a student of architecture; Foster as a graduated radical architect; Foster as an emergent architect on the global stage; Foster as the architect leading one of the largest firms in the world; and Foster as an architectural bon viveur, globetrotting and speculating on a global future.

![]()

Throughout the exhibition there is a focus on how architecture can be represented away from its final built form. The curation utilises many methods of showing architecture in a display context, but sketching is the primary mode and present throughout, but especially in the opening room. Vitrines of sketchbooks show the genesis of many well-known projects, as well as unrealised schemes alongside observations, lists, and notes. Foster says that he started properly recording and collecting his sketchbooks in the 1970s, but the earliest in the show dates from 1948 and his O-Level work, an open page showing a page of descriptive handwriting adjacent to meticulous sketches of fan vaulting.

“I remember art classes for O-Level and the history of architecture being part of that curriculum,” Foster explains, and the history of architecture, and how it aligns to his ongoing vision for the future, is also a recurring theme. From his university studies, framed pencil drawings of a windmill in Bourne and a cut-away showing the roof structure of a medieval barn in Burwell show an interest in the past, but it was not the past that the university expected their students to show an interest in: “Measured drawing was an important discipline in Manchester, but over the history of the school it had always had to be a Georgian building, because a Georgian building was considered architecture,” the architect explains, adding that “this barn was not considered architecture, but for me it was the very essence of architecture.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The pencil is an important tool to Foster, whether applied with the clinicality of a scaled drawing or diagram, or more loosely deployed in a sketch. It is how his ideas first emerge, as row upon row of notebook evidences. “A building starts with a sketch,” he proclaims, and it is a skill that he believes should still be central to an architectural education and practice not despite CAD and digital drawing, but because of it. “Perhaps there are schools of architecture that still encourage life drawing,” he wonders, and as seamlessly as his studies of historic windmills feed into ideas for sustainable energy in an unknown future, adds “if you develop a skill with a pencil as a tool, then that's going to transfer into the way in which you use computers as a tool.”

In the opening room there is also a display of photographic slides, large grids of images Foster has made on his many travels as a student and since. Excitedly he flits between the buildings and places. The Schindler House, Bradbury Building, an Aztec pyramid, a ski slope in the Alps, agricultural structures, a Copenhagen building by Arne Jacobsen, Torre Velasca in Milan. Then he finds nodes and connections between them, his finger traces an imaginary line between the agricultural structure and a photo of his seminal Honk Kong and Shanghai Bank. The photos, the sketching, and the engineering studies are all about looking and understanding as components leading to connecting and constructing.

![]()

After the drawing room, the main open-plan gallery space where the visitor is immediately confronted with not just drawings and architectural models of all scales, but also a number of other objects: a Richard Buckminster Fuller Dymaxion car, a Sol Lewitt grid sculpture, a model zeppelin, a Constantin Brancusi columnar sculpture, a work by Umberto Boccioni, an Ai Weiwei geometric sphere, and even an aeroplane hanging from the ceiling.

These works all have a story, but their presence also allows silent conversation with the drawings, models, and engineering sections in view around them. Migayrou tells recessed.space that “for Norman Foster there is no hierarchy between a car, a plane, architecture, an urban territory, or any scale – he just wants to have a look at the intelligence of the conception and performativity of the concepts.”

The room is also full of drawings. There are many by Foster himself, but also by many of the vast team who have supported his ideas over the decades. “I've tried to celebrate the drawings and works of others,” Foster explains, before pointing out drawings by Helmut Jacoby, Birkin Haward, and Armstrong Yakubu.

![]()

![]()

It’s models, however, which keep fighting for attention in this crowded curation – some so large and immaculately produced that they must have a budget larger than many small architectural projects. There are 1:10 engineering elements, tiny maquettes, and everything in between. Under the heading Vertical City, a row of tall skyscraper models stands against a wide vista of the Paris skyline. A number of older schemes have been re-presented with new diorama style models, light boxes built into the wall showing a cut-through of the scheme in intricate detail, a fun call back to an historic mode of display.

What’s exciting in places, for those visiting who know Foster’s architecture well, is in a number of instances a model of a celebrated building – such as the Carré d'Art museum in Nîmes or the Apple HQ in Cupertino – is shown alongside numerous models of schemes rejected en route to the final design. For an industry which is largely recognised only on a completed design and what is finally built, to see so many alternative realities presented, to make present the processes towards an outcome, is refreshing.

Next to a model of the final Apple design, a perfect circle enclosing a vast green landscape, a series of wall-mounted models shows 15 alternative spatial arrangements for the site, all ideas which were explored and tested before a final decision of the circle was made. Foster explains that “it makes the point that that circle is not a kind of instant one liner, that it came about after ten months of intensive study with Steve Jobs, and you can start to see the evolution.”

A final room, looking at future imaginaries and space architecture, pulls the representation of architecture into more modern aesthetics, utilising 3D printing and luscious digital renders. But there is still space for sketching and the pencil. It is a continuous form of representing architecture and idea, going right back to that O-Level sketchbook. It is also a craft Norman Foster is still committed to, including with life drawing classes in his offices and, alongside Foster + Partners Art Director Narinder Sagoo, a project going right back to where he started: “We bring primary school kids into the studio, and we run a nationwide drawing campaign.”

![]()

The main exhibition is a rich agglomeration of drawings, models of Foster’s architecture, alongside assorted artworks and engineering which have inspired him. But before the visitor encounters this deeply curated collection, an anteroom packed with drawings, slide photographs, and sketchbooks sets the scene for the architect’s creative approach.

It is a fascinating entrance to the exhibition, rich in approaches to representing imagination, with an eye and style which can be tracked across seven decades of drawing. The exhibition’s curator, Frédéric Migayrou, tells recessed.space that this room is designed “to penetrate the spirit, to get inside the head of the architect.” In reality, we get into the head of many architects: Foster as a student of architecture; Foster as a graduated radical architect; Foster as an emergent architect on the global stage; Foster as the architect leading one of the largest firms in the world; and Foster as an architectural bon viveur, globetrotting and speculating on a global future.

Throughout the exhibition there is a focus on how architecture can be represented away from its final built form. The curation utilises many methods of showing architecture in a display context, but sketching is the primary mode and present throughout, but especially in the opening room. Vitrines of sketchbooks show the genesis of many well-known projects, as well as unrealised schemes alongside observations, lists, and notes. Foster says that he started properly recording and collecting his sketchbooks in the 1970s, but the earliest in the show dates from 1948 and his O-Level work, an open page showing a page of descriptive handwriting adjacent to meticulous sketches of fan vaulting.

“I remember art classes for O-Level and the history of architecture being part of that curriculum,” Foster explains, and the history of architecture, and how it aligns to his ongoing vision for the future, is also a recurring theme. From his university studies, framed pencil drawings of a windmill in Bourne and a cut-away showing the roof structure of a medieval barn in Burwell show an interest in the past, but it was not the past that the university expected their students to show an interest in: “Measured drawing was an important discipline in Manchester, but over the history of the school it had always had to be a Georgian building, because a Georgian building was considered architecture,” the architect explains, adding that “this barn was not considered architecture, but for me it was the very essence of architecture.”

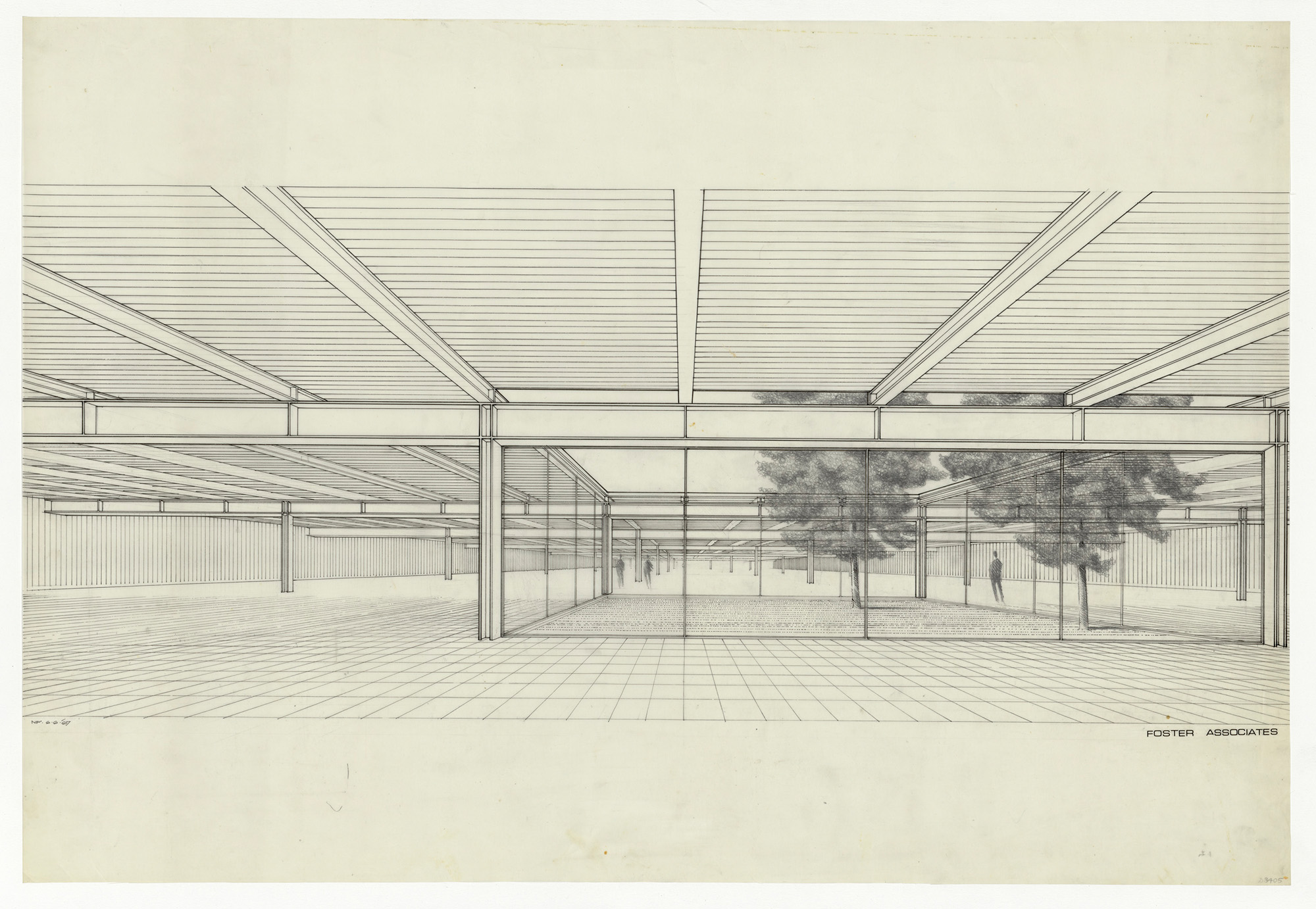

figs.i-iv

The pencil is an important tool to Foster, whether applied with the clinicality of a scaled drawing or diagram, or more loosely deployed in a sketch. It is how his ideas first emerge, as row upon row of notebook evidences. “A building starts with a sketch,” he proclaims, and it is a skill that he believes should still be central to an architectural education and practice not despite CAD and digital drawing, but because of it. “Perhaps there are schools of architecture that still encourage life drawing,” he wonders, and as seamlessly as his studies of historic windmills feed into ideas for sustainable energy in an unknown future, adds “if you develop a skill with a pencil as a tool, then that's going to transfer into the way in which you use computers as a tool.”

In the opening room there is also a display of photographic slides, large grids of images Foster has made on his many travels as a student and since. Excitedly he flits between the buildings and places. The Schindler House, Bradbury Building, an Aztec pyramid, a ski slope in the Alps, agricultural structures, a Copenhagen building by Arne Jacobsen, Torre Velasca in Milan. Then he finds nodes and connections between them, his finger traces an imaginary line between the agricultural structure and a photo of his seminal Honk Kong and Shanghai Bank. The photos, the sketching, and the engineering studies are all about looking and understanding as components leading to connecting and constructing.

After the drawing room, the main open-plan gallery space where the visitor is immediately confronted with not just drawings and architectural models of all scales, but also a number of other objects: a Richard Buckminster Fuller Dymaxion car, a Sol Lewitt grid sculpture, a model zeppelin, a Constantin Brancusi columnar sculpture, a work by Umberto Boccioni, an Ai Weiwei geometric sphere, and even an aeroplane hanging from the ceiling.

These works all have a story, but their presence also allows silent conversation with the drawings, models, and engineering sections in view around them. Migayrou tells recessed.space that “for Norman Foster there is no hierarchy between a car, a plane, architecture, an urban territory, or any scale – he just wants to have a look at the intelligence of the conception and performativity of the concepts.”

The room is also full of drawings. There are many by Foster himself, but also by many of the vast team who have supported his ideas over the decades. “I've tried to celebrate the drawings and works of others,” Foster explains, before pointing out drawings by Helmut Jacoby, Birkin Haward, and Armstrong Yakubu.

It’s models, however, which keep fighting for attention in this crowded curation – some so large and immaculately produced that they must have a budget larger than many small architectural projects. There are 1:10 engineering elements, tiny maquettes, and everything in between. Under the heading Vertical City, a row of tall skyscraper models stands against a wide vista of the Paris skyline. A number of older schemes have been re-presented with new diorama style models, light boxes built into the wall showing a cut-through of the scheme in intricate detail, a fun call back to an historic mode of display.

What’s exciting in places, for those visiting who know Foster’s architecture well, is in a number of instances a model of a celebrated building – such as the Carré d'Art museum in Nîmes or the Apple HQ in Cupertino – is shown alongside numerous models of schemes rejected en route to the final design. For an industry which is largely recognised only on a completed design and what is finally built, to see so many alternative realities presented, to make present the processes towards an outcome, is refreshing.

Next to a model of the final Apple design, a perfect circle enclosing a vast green landscape, a series of wall-mounted models shows 15 alternative spatial arrangements for the site, all ideas which were explored and tested before a final decision of the circle was made. Foster explains that “it makes the point that that circle is not a kind of instant one liner, that it came about after ten months of intensive study with Steve Jobs, and you can start to see the evolution.”

A final room, looking at future imaginaries and space architecture, pulls the representation of architecture into more modern aesthetics, utilising 3D printing and luscious digital renders. But there is still space for sketching and the pencil. It is a continuous form of representing architecture and idea, going right back to that O-Level sketchbook. It is also a craft Norman Foster is still committed to, including with life drawing classes in his offices and, alongside Foster + Partners Art Director Narinder Sagoo, a project going right back to where he started: “We bring primary school kids into the studio, and we run a nationwide drawing campaign.”

Norman Foster founded Foster + Partners in 1967, and over

five decades he has established a sustainable approach to the design of the

built environment. He believes that the quality of our surroundings affects the

quality of our lives, and is driven by his passion for innovation and excellence.

He is also president of the Norman Foster Foundation, based in Madrid. In 1999,

he was honoured by The Queen with a life peerage, taking the title Lord Foster

of Thames Bank. Norman is a keen pilot, enjoys cross-country skiing and

cycling.

www.fosterandpartners.com

visit

The Norman Foster exhibition is organised by the Centre Pompidou, with the

collaboration of Foster + Partners and the Norman Foster Foundation. It runs at

the Centre Pompidou, Paris, until to 7 August 2023. More details and tickets

available at:

www.centrepompidou.fr/en/program/calendar/event/Lan1nnY

images

fig.i Factory for Reliance Controls (1965).

© Norman Foster

fig.ii Amenity Centre, Fred Olsen (1968).

© Norman Foster

fig.iii Collserola Tower (1992).

© Norman Foster

fig.iv Post Mill at Bourne (1958).

© Norman Foster

installation images © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

publication date

06 June 2023

tags

Apple, Barn, Car, Umberto Boccioni, Constantin Brancusi, Richard Buckminster Fuller, Centre Pompidou, Computer, Diorama, Drawing, Engineering, Norman Foster, Foster + Partners, Birkin Haward, Helmut Jacoby, Steve Jobs, Sol Lewitt, University of Manchester, Frédéric Migayrou, Model, Paris, Pencil, Photography, Narinder Sagoo, Sketch, Sketchbook, Ai Weiwei, Windmill, Armstrong Yakubu

www.centrepompidou.fr/en/program/calendar/event/Lan1nnY