Dear Earth: shining artificial light on the

climate crisis

At London’s Hayward Gallery, nature & our toxic relationship to it falls under the spotlight as a range of artists centre caring as a form of resistance. Tim Waterman visited to discover both hope & doom in equal measure, but wonders if at its core, art overly-romanticises a crisis requiring a more direct response.

A time of crisis is a

turning point, a specific duration in which an outcome will become apparent.

Will the fever break? Or will the patient die? Climate change and biodiversity

loss, then, cannot be seen as crises, as they are both ongoing processes which

have developing consequences which will require long-term thinking and

planning. Ecosystems everywhere have already suffered irreversible losses. Much

of recent environmental literature addresses this directly – from Donna

Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble to Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing et al.’s Arts

of Living on a Damaged Planet.[1]

The crisis, then, must be one of consciousness and its relation to necessary action. Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis addresses a crisis of knowledge and acknowledgement, resonating with themes which are growing in importance: the question of care being central among these, and of hope, foregrounded in the exhibition’s subtitle. In essence, there is a relation in the exhibition’s framing and context which calls up the problem John Berger identifies in his famous essay The White Bird: “you can’t talk about aesthetics without talking about the principle of hope and the existence of evil”.[2] I can’t help but think it also faces the problem he identifies at the end of the essay, “Art does not imitate nature, it imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature”.[3]

![]()

![]()

A central problem for this exhibition, though, is that a crisis (never mind the existence of evil) is tiring, and I’m sure I’m not alone as a visitor to the exhibition feeling I’m very well connected with the ideas presented, and that I might not be the most important audience for the work. Indeed, no one willing to pay £15 to enter the gallery is probably amongst the most important audience for the work. And the sense of fatigue with the subject matter is inescapable despite the curators’ stated desire to impart a sense of hope instead of doom.

So, what might be amplified, confirmed, and made social? Surely it is action, determination, mutual endeavour, and, importantly, plucking up the mettle for an all-out battle with the recalcitrant forces aligned in the destruction of the biosphere. Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline[4] perhaps galvanises such sentiment and its will to action, but that’s not the kind of radicalism on view here. You’ll look in vain for a copy in the gift shop.

![]()

![]()

![]()

There is plenty on exhibit to arouse anger. Richard Mosse’s lurid photographs of abandoned oil infrastructure and neglected spills in the Amazon uses multispectral imaging to make visible environmental damage (also see 00058). These are accompanied by a video installation in which Yanomami people present pleas to the world for intervention against the violence of gold miners poisoning their land and committing ecocide and genocide. The beauty of the imagery, as with Edward Burtynsky’s work, arouses admiration and repulsion at once. Mosse’s video work also more effectively incites anger than Burtynsky’s as the messages are so personal and embodied.

Imani Jacqueline Brown’s documentary work on the toxic legacy of fossil fuels and the chemical industry in the landscapes of emancipated slave communities in Mississippi’s Death Alley invites comparison to the work of Forensic Architecture. Similarly, it assembles evidence to indict colonial and racist practices of industry, planning, and policy, while firing righteous anger to initiate action.

There are layers of meaning in the exhibition to which the title points – that the Earth is dear, as in costly; the object of intimate affection; the subject of an address; and sweet or blessed. Berger, again in The White Bird cautions against the romanticisation of nature. The white bird addressed in the essay is a folk carving, suspended above and wafted by the waves of heat from a stove, “where the neighbours are drinking” while outside “the real birds are freezing to death”.[5]

![]()

![]()

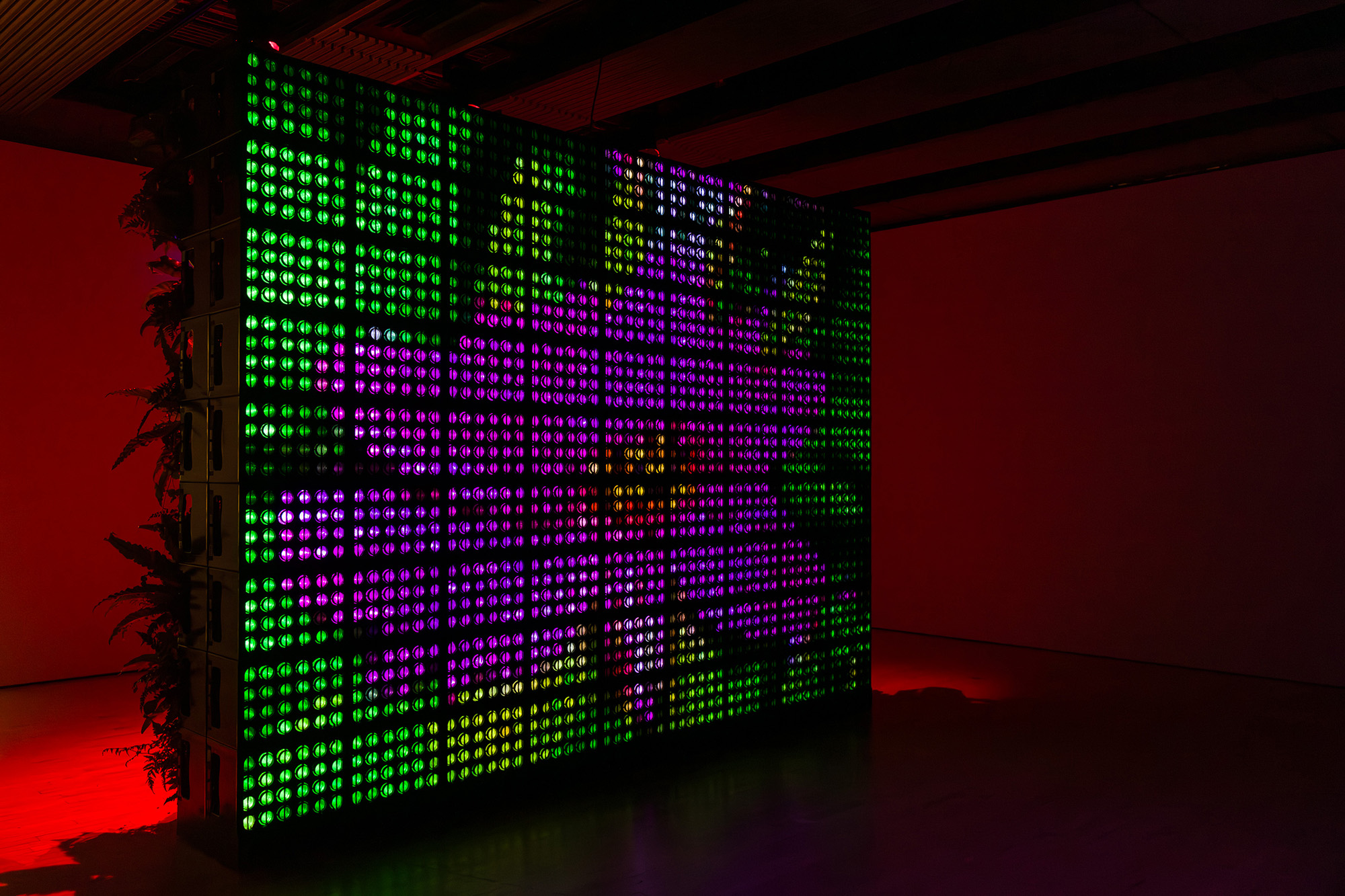

It’s a potent analogy. There, in the gallery, we can be warmed and intoxicated by an infatuation with nature and a call to hope for its recovery, while outside Rishi Sunak grants 100 new North Sea oil and gas extraction licences. There, in the gallery, the real ferns in the Hito Steyerl installation are dying under artificial light, while outside John Gerrard’s film Surrender chuffs water vapour in an intentionally futile gesture into the dry desert air. The Hayward should offer a cocktail as one leaves the gallery – not one for comfort, but one for courage – and then another, a Molotov cocktail with an invitation to be thrown.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

[1] Haraway, Donna J. (2016) Staying with the

Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University

Press.

The crisis, then, must be one of consciousness and its relation to necessary action. Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis addresses a crisis of knowledge and acknowledgement, resonating with themes which are growing in importance: the question of care being central among these, and of hope, foregrounded in the exhibition’s subtitle. In essence, there is a relation in the exhibition’s framing and context which calls up the problem John Berger identifies in his famous essay The White Bird: “you can’t talk about aesthetics without talking about the principle of hope and the existence of evil”.[2] I can’t help but think it also faces the problem he identifies at the end of the essay, “Art does not imitate nature, it imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature”.[3]

Figs.i,ii

A central problem for this exhibition, though, is that a crisis (never mind the existence of evil) is tiring, and I’m sure I’m not alone as a visitor to the exhibition feeling I’m very well connected with the ideas presented, and that I might not be the most important audience for the work. Indeed, no one willing to pay £15 to enter the gallery is probably amongst the most important audience for the work. And the sense of fatigue with the subject matter is inescapable despite the curators’ stated desire to impart a sense of hope instead of doom.

So, what might be amplified, confirmed, and made social? Surely it is action, determination, mutual endeavour, and, importantly, plucking up the mettle for an all-out battle with the recalcitrant forces aligned in the destruction of the biosphere. Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline[4] perhaps galvanises such sentiment and its will to action, but that’s not the kind of radicalism on view here. You’ll look in vain for a copy in the gift shop.

Figs.iii-v

There is plenty on exhibit to arouse anger. Richard Mosse’s lurid photographs of abandoned oil infrastructure and neglected spills in the Amazon uses multispectral imaging to make visible environmental damage (also see 00058). These are accompanied by a video installation in which Yanomami people present pleas to the world for intervention against the violence of gold miners poisoning their land and committing ecocide and genocide. The beauty of the imagery, as with Edward Burtynsky’s work, arouses admiration and repulsion at once. Mosse’s video work also more effectively incites anger than Burtynsky’s as the messages are so personal and embodied.

Imani Jacqueline Brown’s documentary work on the toxic legacy of fossil fuels and the chemical industry in the landscapes of emancipated slave communities in Mississippi’s Death Alley invites comparison to the work of Forensic Architecture. Similarly, it assembles evidence to indict colonial and racist practices of industry, planning, and policy, while firing righteous anger to initiate action.

There are layers of meaning in the exhibition to which the title points – that the Earth is dear, as in costly; the object of intimate affection; the subject of an address; and sweet or blessed. Berger, again in The White Bird cautions against the romanticisation of nature. The white bird addressed in the essay is a folk carving, suspended above and wafted by the waves of heat from a stove, “where the neighbours are drinking” while outside “the real birds are freezing to death”.[5]

Figs.vi,vii

It’s a potent analogy. There, in the gallery, we can be warmed and intoxicated by an infatuation with nature and a call to hope for its recovery, while outside Rishi Sunak grants 100 new North Sea oil and gas extraction licences. There, in the gallery, the real ferns in the Hito Steyerl installation are dying under artificial light, while outside John Gerrard’s film Surrender chuffs water vapour in an intentionally futile gesture into the dry desert air. The Hayward should offer a cocktail as one leaves the gallery – not one for comfort, but one for courage – and then another, a Molotov cocktail with an invitation to be thrown.

Figs.viii-xi

[1] Haraway, Donna J. (2016) Staying with the

Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University

Press.

Tsing, Anna, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, Eds. (2017) Arts

of Living on a Damaged Planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[2] Berger, John (1993) ‘The White Bird’ in The

Sense of Sight. New York: Vintage, p5.

[3] Ibid. p9.

[4] Malm, Andreas (2021) How to Blow Up a

Pipeline. London: Verso.

[5] Berger, John (1993) ‘The White Bird’ in The

Sense of Sight. New York: Vintage, p9.

Tim Waterman is Professor

of Landscape Theory at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL. He is the

author of The Landscape of Utopia: Writings on Everyday Life, Taste, Democracy,

and Design, and editor of Landscape Citizenships with Ed Wall and Jane Wolff, Landscape

and Agency: Critical Essays with Ed Wall, and the Routledge Handbook of

Landscape and Food with Joshua Zeunert.

www.tim-waterman.co.uk

visit

Dear Earth:

Art and Hope in

a Time of Crisis is exhibited at The Hayward Gallery, London, until 03 September.

Further details available at:

www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/art-exhibitions/dear-earth

images

fig.i

Installation

view of Jenny Kendler, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun –

3 Sep 2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

fig.ii

Installation

view of Otobong Nkanga, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun –

3 Sep 2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

fig.iii

Installation view of

Imani Jacqueline Brown, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun –

3 Sep 2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

fig.iv

Installation view of

Richard Mosse, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun – 3 Sep 2023).

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

fig.v,vi

Installation view of Richard Mosse, Dear Earth: Art and Hope

in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun – 3 Sep 2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the

Hayward Gallery.

fig.vii

Installation

view of Hito Steyerl, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun – 3

Sep 2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

fig.viii

Installation view of

Aluaiy Kaumakan, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun – 3 Sep

2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

fig.ix

Installation view of

Himali Singh Soin, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun – 3

Sep 2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

fig.x

Installation view of

Andrea Bowers, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun – 3 Sep

2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

fig.xi

Installation view of

Agnes Denes, Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis (21 Jun – 3 Sep

2023). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the Hayward Gallery.

publication date

07 August 2023

tags

John Berger, Edward Burtynsky, Imani Jacqueline Brown, Climate change, Forensic Architecture, John Gerrard, Donna Haraway, Environment, Hayward Gallery, Andreas Malm, Molotov cocktail, Richard Mosse, Nature, Oil, Hito Steyerl, Rishi Sunak, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Tim Waterman, Yanomami people

Further details available at:

www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/art-exhibitions/dear-earth

images