Jesse Darling at the Turner Prize: a civic waste land

Jesse Darling, one of this year’s shortlisted Turner Prize

hopefuls, has transformed his space in Towner Eastbourne, the competition’s

host venue, into a dystopian transmogrification of our urban civic realm, to

create an anxious and twisted critique of the body in political, surveilled,

controlling landscapes.

The Turner Prize, this year hosted at the Towner Gallery in

Eastbourne, is always a curious mix of four diverse artists and ways of

exhibiting their contemporary practice. There’s often a disjunct of experience

and expectation when moving from one of the four gallery spaces into the next,

with no curatorial or visual language connecting each of the four shortlisted

artists, always making for a unique small group show. Some artists simply

replicate a display of works showed in a previous exhibition elsewhere, some create

a polite and mannered show of their best-of, while others confront the

once-in-a-lifetime offer head on and create a new world to shock and pleasure

the visiting public.

![]()

![]()

Of all the artists exhibiting this year, has done just this. Jesse Darling, who works across sculpture, drawing, text, and installation, has created a Brexity theme park of anxiety, pressure, and instability which draws from infrastructures and architectures of our urban social and civic realms. Transmogrifying inexpensive industrial objects, Darling has created a fever dream of animalistic barriers, a dystopian maypole, and anthropomorphic industry emerging from the walls.

It starts outside the gallery space. A seemingly abandoned billboard illuminates the wall it leans against, barbed wire and a commercial roller-shutter sit above the most unwelcoming of entrances. Anybody with the courage to cross that threshold then finds themselves channelled by steel crowd barriers, narrowing and directing the visitor’s path. The barriers themselves seem to not just be the mechanisms of this crowd control, but perhaps also the instigators – each has extended and elongated legs and seems to be crawling around the gallery space, threatening the humans who dare enter. Another is crawling up the wall as if trying to escape.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Darling draws from the history of land enclosure and privately managed public spaces of modern-day developments. In doing this, ideas around freedom, nature, bodies, and borders are physically tested across an installation that also dips into the domestic to think about self-control, ritual, surveillance, and labour. This gallery space is a reworking of our civic society and its physical manifestation, systems of control and power propogate the space, but they are also seen as weird, mutable, and anxious.

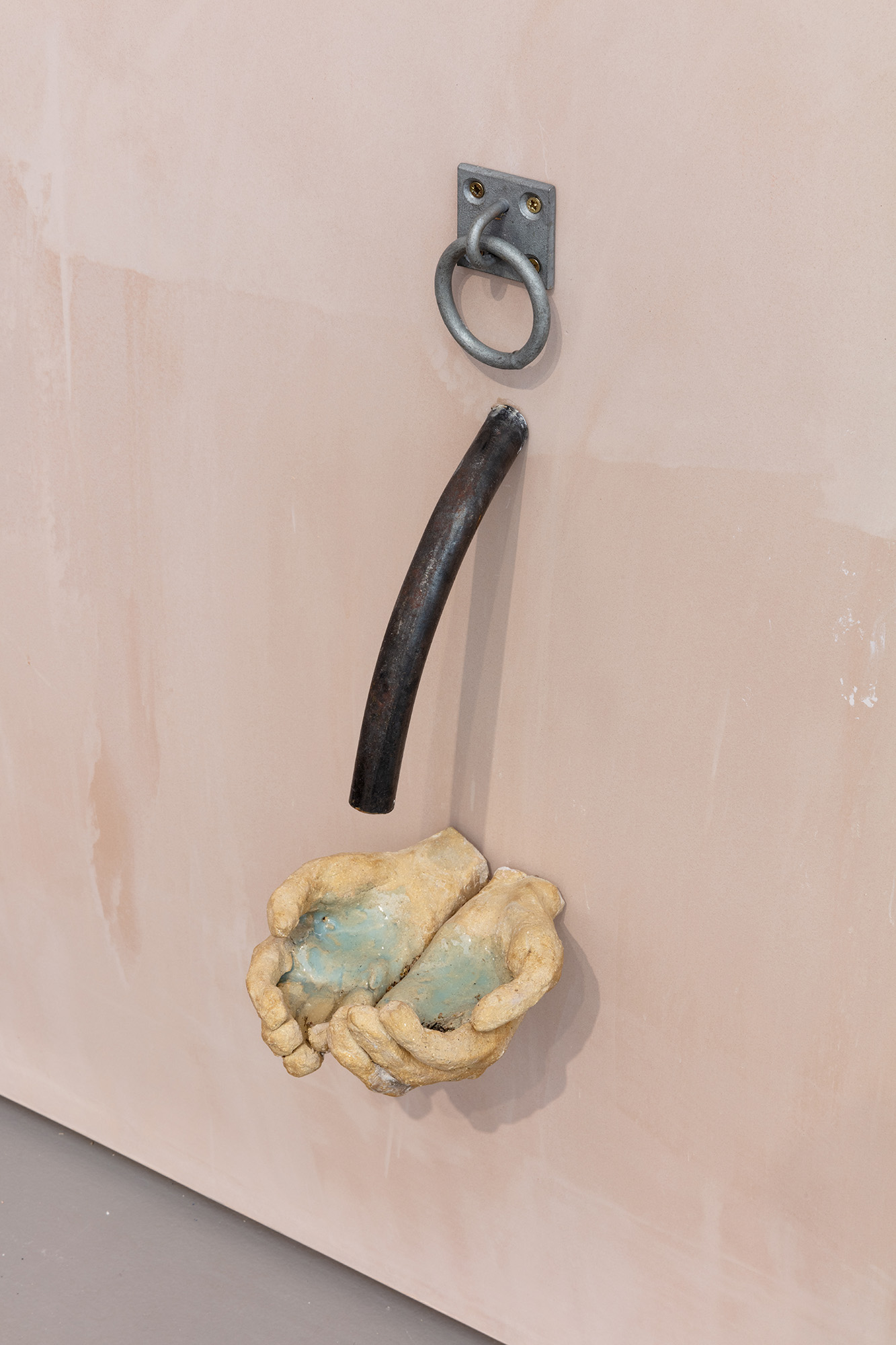

The body – human and non-human – is central to the works, but the others are not often identified. Hands protrude from an unfinished-plasterboard pink wall as if petrified in a moment of exchange, other humdrum materials suddenly take the appearance of life, such as a phallic candle and two bells.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Sad bunting hangs from above, splayed out from a scaffolding pole wrapped in crime-scene-like warning tape, topped with anti-pigeon spikes. It all feels like a national comedown and nobody wants to clear up the detritus. Bursting from the wall is a metal construction that looks like a wayward rollercoaster that has gone off the rails. But perhaps it’s not a downward descent of a big dipper, maybe it’s the opportunity of freedom and escape, a ladder someone else on the other side has smashed through to remind us there are ways to escape control and oppression.

The actual exit, which leads into a gallery full of works by fellow shortlisted artist Barbara Walker, is easier to navigate but no less nervous. Two concrete pillars stand as gateposts, lacework slung between weakly trying to mask the barbed wire above. But on leaving the waste land behind, it is isn’t left at the gate but continues to resonate in the mind, and out in the “real world” – the visitors’ newly primed brain and eyes will see it across every bit of urban Britain’s civic realm they go on to wander.

Of all the artists exhibiting this year, has done just this. Jesse Darling, who works across sculpture, drawing, text, and installation, has created a Brexity theme park of anxiety, pressure, and instability which draws from infrastructures and architectures of our urban social and civic realms. Transmogrifying inexpensive industrial objects, Darling has created a fever dream of animalistic barriers, a dystopian maypole, and anthropomorphic industry emerging from the walls.

It starts outside the gallery space. A seemingly abandoned billboard illuminates the wall it leans against, barbed wire and a commercial roller-shutter sit above the most unwelcoming of entrances. Anybody with the courage to cross that threshold then finds themselves channelled by steel crowd barriers, narrowing and directing the visitor’s path. The barriers themselves seem to not just be the mechanisms of this crowd control, but perhaps also the instigators – each has extended and elongated legs and seems to be crawling around the gallery space, threatening the humans who dare enter. Another is crawling up the wall as if trying to escape.

Darling draws from the history of land enclosure and privately managed public spaces of modern-day developments. In doing this, ideas around freedom, nature, bodies, and borders are physically tested across an installation that also dips into the domestic to think about self-control, ritual, surveillance, and labour. This gallery space is a reworking of our civic society and its physical manifestation, systems of control and power propogate the space, but they are also seen as weird, mutable, and anxious.

The body – human and non-human – is central to the works, but the others are not often identified. Hands protrude from an unfinished-plasterboard pink wall as if petrified in a moment of exchange, other humdrum materials suddenly take the appearance of life, such as a phallic candle and two bells.

Sad bunting hangs from above, splayed out from a scaffolding pole wrapped in crime-scene-like warning tape, topped with anti-pigeon spikes. It all feels like a national comedown and nobody wants to clear up the detritus. Bursting from the wall is a metal construction that looks like a wayward rollercoaster that has gone off the rails. But perhaps it’s not a downward descent of a big dipper, maybe it’s the opportunity of freedom and escape, a ladder someone else on the other side has smashed through to remind us there are ways to escape control and oppression.

The actual exit, which leads into a gallery full of works by fellow shortlisted artist Barbara Walker, is easier to navigate but no less nervous. Two concrete pillars stand as gateposts, lacework slung between weakly trying to mask the barbed wire above. But on leaving the waste land behind, it is isn’t left at the gate but continues to resonate in the mind, and out in the “real world” – the visitors’ newly primed brain and eyes will see it across every bit of urban Britain’s civic realm they go on to wander.

Jesse Darling was born in Oxford in 1981. Darling studied at

Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London and completed an MFA at Slade

School of Fine Art, University College London in 2014. In 2021, he released his

first collection of poetry, Virgins, Monitor Books (Salford, UK). Jesse Darling

lives and works in Berlin, Germany.

Solo exhibitions include: Miserere, St James’s Piccadilly,

London, UK (2022); Gravity Road, Kunstverein Freiburg, Germany (2020); Crevé, Triangle

France – Astérides, Marseille, France (2019) and The Ballad of Saint Jerome,

Art Now, Tate Britain, London, UK (2018).

Group exhibitions include: Exposed, Palais de

Tokyo, Paris, France (2023); Trickster Figures: Sculpture and the Body, MK

Gallery, Milton Keynes, UK (2023); Barbe à Papa, CAPC Bordeaux, France (2022); Drawing

in the Continuous Present, The Drawing Center, New York, USA (2022); WALK!,

Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Germany (2022); Crip Time, MMK Museum für Moderne

Kunst, Frankfurt, Germany (2021); A Fine Line, Kunsthalle Bremen, Germany (2020);

Transcorporealities, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany (2019) and May You Live in

Interesting Times, 58th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy (2019).

www.bravenewwhat.org

The

Turner Prize was established in 1984 and is awarded each year to a British

artist for an outstanding exhibition or other presentation of their work. The

Turner Prize award is £55,000 with £25,000 going to the winner and £10,000 each

for the other shortlisted artists.The members of the Turner Prize 2023 jury are

Martin Clark, Director, Camden Art Centre; Cédric Fauq, Chief Curator, Capc

musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux; Melanie Keen, Director of Wellcome Collection;

and Helen Nisbet, CEO and Artistic Director, Cromwell Place, and Artistic

Director, Art Night. The jury is chaired by Alex Farquharson, Director, Tate

Britain. The Turner Prize 2023 is curated by Noelle Collins, Exhibitions and

Offsite Curator at Towner Eastbourne.

www.tate.org.uk/art/turner-prize

Towner

Eastbourne has collected and exhibited contemporary art for 100 years, sitting where

the coast and the South Downs meet. Towner presents exhibitions of national and

international importance for audiences in Eastbourne, the UK and beyond,

showcasing the most exciting and creative developments in modern and

contemporary art. Towner develops and supports artistic practice and

collaborates with individuals, communities and organisations to deliver an

inclusive, connected and accessible public programme of live events, film and

learning. Towner’s collection of almost 5,000 works is best known for its

modern British art – including the largest and most significant body of work by

Eric Ravilious (1903-42) – and a growing collection of international

contemporary art including Elizabeth Price, Rachel Jones, Dineo Seshee Bopape,

Wolfgang Tillmans and Andy Warhol.

www.townereastbourne.org.uk

www.tate.org.uk/art/turner-prize