Mancunian ecologies: A Fine Toothed Comb, curated by Lubaina Himid

At HOME, Manchester, Turner Prize-winning artist Lubaina Himid acts as curator of three artists exploring hidden layers of the city’s culture and ecology. Himid herself presents new commissions between the works of Magda Stawarska, Rebecca Chesney, and Tracy Hill in an exhibition Paul Dobraszczyk finds useful as a metaphor for a nurturing politics our urban landscapes might benefit from.

Back in 2001, urban critic Mike Davis reflected on the

lack of understanding of what he termed “urban ecology”. Charting the

longstanding fascination with dead cities – urban environments, both

real and imagined, reduced to ruin by bombs, disinvestment, pandemics, aliens,

and so on. Davis argued that studying the ecology of cities was an urgent task,

given the dawning realisation that humans were outstripping nature in

their pursuit of rapid urbanisation.

Over two decades later, when the human-built world is now more extensive than nature itself, Davis’s plea possesses even more urgency, even as urban ecology is now a burgeoning subject in architectural education, especially in landscape design. This is not so much a consequence of ignorance but rather of the acceleration of capitalism. In 2001, Davis also thought that skyscrapers would have no future – especially after 9/11. If he were alive today, Davis would be gobsmacked by the transformation of central Manchester and Salford into a city of towers – 50 built in the last two decades alone, with another 50 planned; each successive skyscraper jostling for ascendancy.

![]()

In this context, the four main works presented in A Fine Toothed Comb offer a salutary corrective to this recent onrush, and uprush, of human construction. The space in which the exhibits are housed – a dedicated art gallery within HOME, which opened in 2013 – looks out on the cluster of towers masterminded by Manchester architect Ian Simpson, all built in the last decade. It is, in some ways, a space that is the epitome of neoliberal capital: HOME fronts Tony Wilson Place (named after the city’s much-loved impresario and founder of Factory Records), where a statue of Friedrich Engels, sourced from post-Soviet Ukraine, looks out over a scene of capitalist triumph with stony-faced indifference.

![]()

![]()

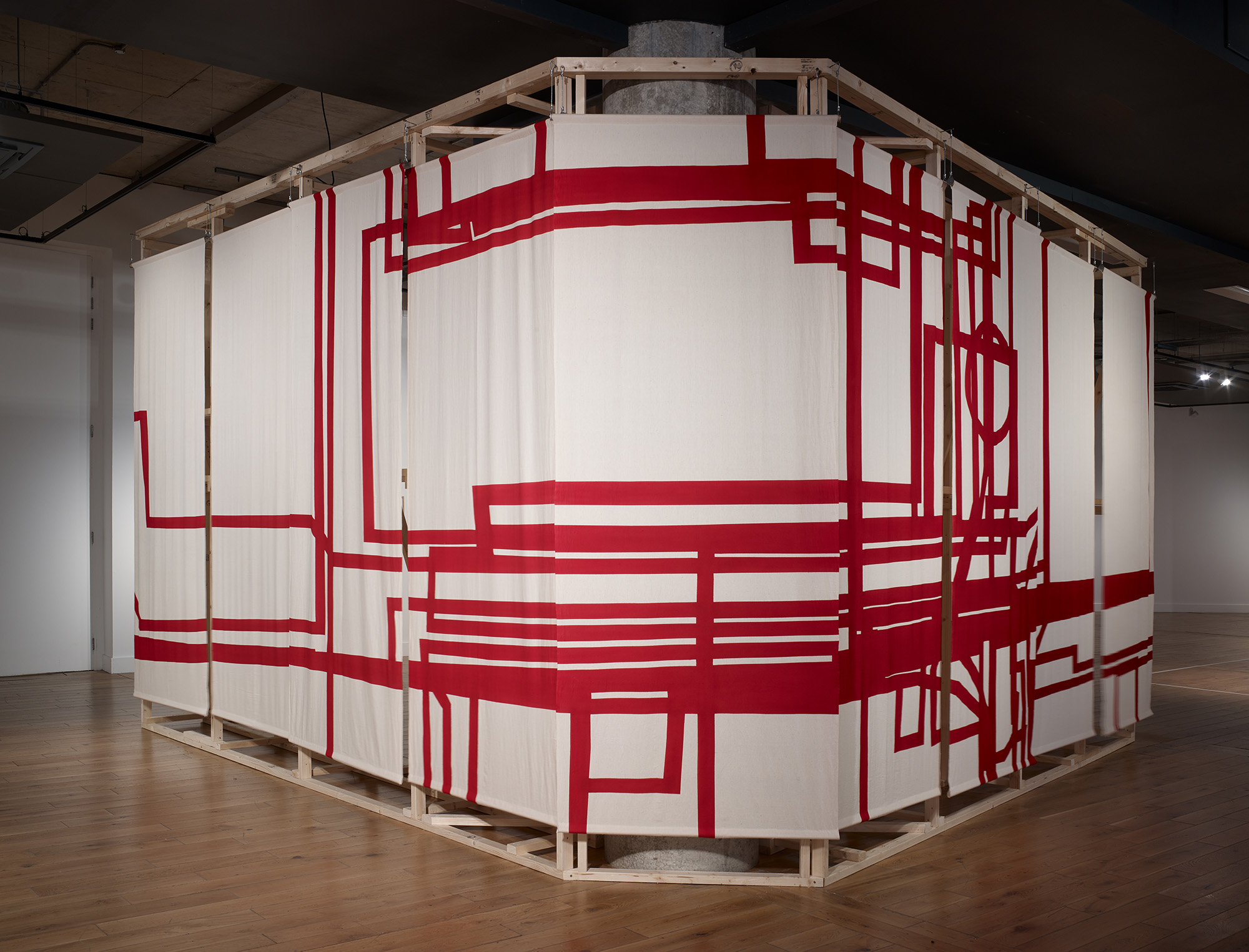

In A Fine Toothed Comb, Rebecca Chesney provides us with the most explicit take on contemporary Manchester: her installation Cause and Affect (2020) is a textile work that features a cryptic arrangement of red lines, gleaned from the many different planning applications submitted over the years for the urban landscape around HOME itself. Behind this textile work, a speaker plays a dawn chorus of birdsong recorded nearby by the artist on what was once a patch of waste-ground, but which has now been redeveloped. The very fact that we readily use words like waste-ground and redeveloped points to a pervasive anthropocentrism in how we understand cities.

In an urban landscape, it seems, there can be no land that is simply there for other lifeforms: even green spaces like parks are primarily for human, rather than more-than-human, use. In Cause and Affect, we’re asked to question this assumption. Human construction not only results in the erasure of other life, but also the abstraction of the environment itself. Indeed, in this installation, the birdsong makes more sense than the seemingly random scrawls that tell of human plans.

![]()

Another aspect of urban ecology not often acknowledged relates to the environment that lies beneath our feet, the subject of Tracy Hill’s enigmatic installation Sugere, from the Latin word meaning to spring up or rise. After discovering the presence of a natural spring beneath HOME, Hills consulted with a water dowser and a geologist to translate the effect of this hidden water source, particularly the sounds it makes, into lithography – a technique developed in printing that involves drawing on stone. Hills then translated these into a series of patterns painted on a curved wall and adjacent floor of the gallery space.

The carbon and silicon dioxide used to create these patterns links water to geology, flows of liquid translated into flows of matter. Yet, these patterns are inscrutable, reflecting the fact that the subterranean spaces of cities are also, sometimes quite literally, cryptic. The healthy functioning of modern cities is predicated on a certain degree of burrowing - the creation of basic infrastructure like sewers and utility tunnels for instance – but these spaces always remain somehow removed from the world above ground, as if the primal human associations of the underground with darkness and danger can never be dispelled.

![]()

![]()

Urban ecology also encompasses a city’s architecture, as seen in Magda Stawarska’s four-channel video work Music and Silence. The focus of this work is two prominent buildings in Manchester and Łódź, Poland: respectively, the central library, completed in 1934, and Karol Poznański Palace (now a music academy), built in 1904. In the library, silence reigns, the cupola of the circular reading room enforcing a certain kind of behaviour on its occupants (Mancunians know that any sound made in that space is magnified by the architecture itself). In the former palace, a cellist plays a piece of flowing music that mirrors the florid ornamentation of the building, its bright cupola a sign of freedom and creative expression.

Once dubbed the Polish Manchester, Łódź was, like its British pioneer, a centre of industrial textile production (even in 1989 when I visited, it was shrouded in smoke pollution like Manchester was until the 1970s). An investigation into how architecture affects human behaviour, Music and Silence also points to the vital role of globalisation in the history of Manchester, namely, the way in which, not so long ago, its industrial prowess was the model for many other cities across the world. Today, of course, industrial production has far fewer positive connotations and Manchester’s global affect is more a consequence of money from afar flowing back into the city than the reverse.

![]()

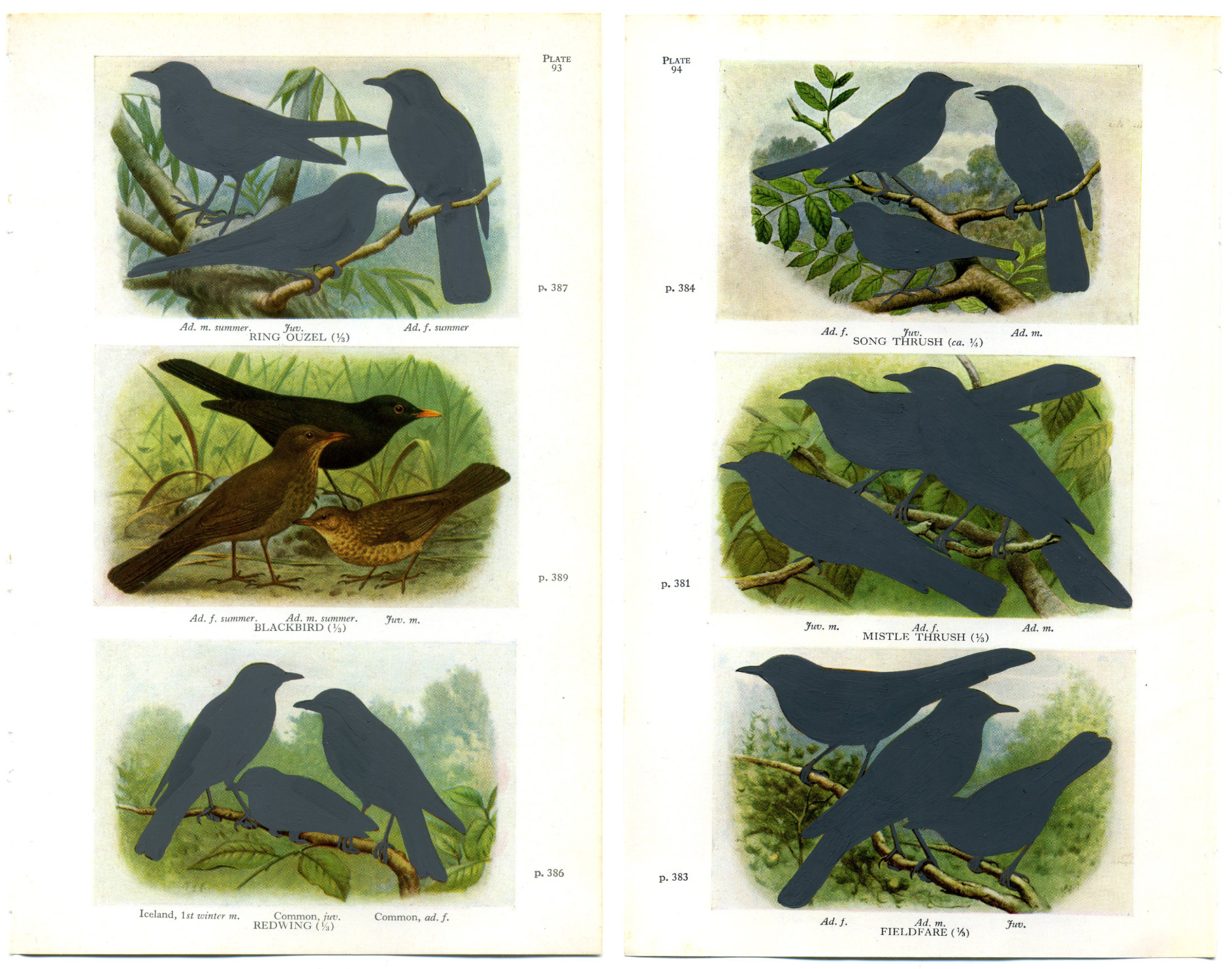

The most striking and direct work on show here is another installation by Rebecca Chesney, titled Red, Amber, Green. Here, the artist has taken all the colour plates from a guidebook to British birds published in the 1950s and then greyed-out those species currently listed as endangered by the RSPB (their Red and Amber lists). The 120 plates reveal just how many bird species in Britain may disappear in the coming decades – a result of habitat destruction, global heating, and loss of insects and nesting spaces. Just how this litany of woe relates to Manchester is not made clear but, coupled with Chesney’s textile piece, its intention is nonetheless clear: to force an awareness of the specifics of mass extinction.

By revealing what might be lost, Chesney wants us to care about these particular birds because they’re the ones that are close to hand. We may never have seen or heard a nightingale in Manchester (a Red List species) but we’ve all probably encountered a starling or a house sparrow (birds also on the Red List). And if we know they are in precipitous decline, maybe we will care more for them.

![]()

![]()

The curator of A Fine Toothed Comb, Turner-prize winning artist Lubaina Himid, has exhibited some of her own works between the four principal installations: paintings on found objects that speak of human precarity in the city, namely how so many lives could unravel at any moment and which Himid describes as a “frighteningly contemporary state.” It is this theme of precarity which undergirds all the works on show here, and each are invested with their own distinct political charge. Yet, this is a politics that evades any bounded definition, encompassing as it does the politics of birds, land, planning, housing, libraries, palaces, stone, rock, water, music and language.

If we are to take a subject like urban ecology seriously – and I would argue that we must do so urgently – then it means just such an expansion of what is meant by politics. For cities are arguably the richest and most diverse environments on earth, once we forgo the distinction we so often make between biodiversity and human diversity.

What this subtle and luminous exhibition demonstrates is that by breaking down this categorical distinction between humans and other organisms, we can learn to pay attention to and care for all manner of things, living and inert, that surround us at every moment in the cities in which we increasingly live. But this will only come about if we also nurture a very different kind of politics than that which now governs how cities are made (and unmade). We need a politics that, like the art displayed here, is a carefully wielded fine toothed comb rather than a blunt instrument of destruction.

![]()

![]()

Over two decades later, when the human-built world is now more extensive than nature itself, Davis’s plea possesses even more urgency, even as urban ecology is now a burgeoning subject in architectural education, especially in landscape design. This is not so much a consequence of ignorance but rather of the acceleration of capitalism. In 2001, Davis also thought that skyscrapers would have no future – especially after 9/11. If he were alive today, Davis would be gobsmacked by the transformation of central Manchester and Salford into a city of towers – 50 built in the last two decades alone, with another 50 planned; each successive skyscraper jostling for ascendancy.

Fig.i

In this context, the four main works presented in A Fine Toothed Comb offer a salutary corrective to this recent onrush, and uprush, of human construction. The space in which the exhibits are housed – a dedicated art gallery within HOME, which opened in 2013 – looks out on the cluster of towers masterminded by Manchester architect Ian Simpson, all built in the last decade. It is, in some ways, a space that is the epitome of neoliberal capital: HOME fronts Tony Wilson Place (named after the city’s much-loved impresario and founder of Factory Records), where a statue of Friedrich Engels, sourced from post-Soviet Ukraine, looks out over a scene of capitalist triumph with stony-faced indifference.

Figs.ii.iii

In A Fine Toothed Comb, Rebecca Chesney provides us with the most explicit take on contemporary Manchester: her installation Cause and Affect (2020) is a textile work that features a cryptic arrangement of red lines, gleaned from the many different planning applications submitted over the years for the urban landscape around HOME itself. Behind this textile work, a speaker plays a dawn chorus of birdsong recorded nearby by the artist on what was once a patch of waste-ground, but which has now been redeveloped. The very fact that we readily use words like waste-ground and redeveloped points to a pervasive anthropocentrism in how we understand cities.

In an urban landscape, it seems, there can be no land that is simply there for other lifeforms: even green spaces like parks are primarily for human, rather than more-than-human, use. In Cause and Affect, we’re asked to question this assumption. Human construction not only results in the erasure of other life, but also the abstraction of the environment itself. Indeed, in this installation, the birdsong makes more sense than the seemingly random scrawls that tell of human plans.

Fig.iv

Another aspect of urban ecology not often acknowledged relates to the environment that lies beneath our feet, the subject of Tracy Hill’s enigmatic installation Sugere, from the Latin word meaning to spring up or rise. After discovering the presence of a natural spring beneath HOME, Hills consulted with a water dowser and a geologist to translate the effect of this hidden water source, particularly the sounds it makes, into lithography – a technique developed in printing that involves drawing on stone. Hills then translated these into a series of patterns painted on a curved wall and adjacent floor of the gallery space.

The carbon and silicon dioxide used to create these patterns links water to geology, flows of liquid translated into flows of matter. Yet, these patterns are inscrutable, reflecting the fact that the subterranean spaces of cities are also, sometimes quite literally, cryptic. The healthy functioning of modern cities is predicated on a certain degree of burrowing - the creation of basic infrastructure like sewers and utility tunnels for instance – but these spaces always remain somehow removed from the world above ground, as if the primal human associations of the underground with darkness and danger can never be dispelled.

Figs.v,vi

Urban ecology also encompasses a city’s architecture, as seen in Magda Stawarska’s four-channel video work Music and Silence. The focus of this work is two prominent buildings in Manchester and Łódź, Poland: respectively, the central library, completed in 1934, and Karol Poznański Palace (now a music academy), built in 1904. In the library, silence reigns, the cupola of the circular reading room enforcing a certain kind of behaviour on its occupants (Mancunians know that any sound made in that space is magnified by the architecture itself). In the former palace, a cellist plays a piece of flowing music that mirrors the florid ornamentation of the building, its bright cupola a sign of freedom and creative expression.

Once dubbed the Polish Manchester, Łódź was, like its British pioneer, a centre of industrial textile production (even in 1989 when I visited, it was shrouded in smoke pollution like Manchester was until the 1970s). An investigation into how architecture affects human behaviour, Music and Silence also points to the vital role of globalisation in the history of Manchester, namely, the way in which, not so long ago, its industrial prowess was the model for many other cities across the world. Today, of course, industrial production has far fewer positive connotations and Manchester’s global affect is more a consequence of money from afar flowing back into the city than the reverse.

Fig.vii

The most striking and direct work on show here is another installation by Rebecca Chesney, titled Red, Amber, Green. Here, the artist has taken all the colour plates from a guidebook to British birds published in the 1950s and then greyed-out those species currently listed as endangered by the RSPB (their Red and Amber lists). The 120 plates reveal just how many bird species in Britain may disappear in the coming decades – a result of habitat destruction, global heating, and loss of insects and nesting spaces. Just how this litany of woe relates to Manchester is not made clear but, coupled with Chesney’s textile piece, its intention is nonetheless clear: to force an awareness of the specifics of mass extinction.

By revealing what might be lost, Chesney wants us to care about these particular birds because they’re the ones that are close to hand. We may never have seen or heard a nightingale in Manchester (a Red List species) but we’ve all probably encountered a starling or a house sparrow (birds also on the Red List). And if we know they are in precipitous decline, maybe we will care more for them.

Figs.viii,ix

The curator of A Fine Toothed Comb, Turner-prize winning artist Lubaina Himid, has exhibited some of her own works between the four principal installations: paintings on found objects that speak of human precarity in the city, namely how so many lives could unravel at any moment and which Himid describes as a “frighteningly contemporary state.” It is this theme of precarity which undergirds all the works on show here, and each are invested with their own distinct political charge. Yet, this is a politics that evades any bounded definition, encompassing as it does the politics of birds, land, planning, housing, libraries, palaces, stone, rock, water, music and language.

If we are to take a subject like urban ecology seriously – and I would argue that we must do so urgently – then it means just such an expansion of what is meant by politics. For cities are arguably the richest and most diverse environments on earth, once we forgo the distinction we so often make between biodiversity and human diversity.

What this subtle and luminous exhibition demonstrates is that by breaking down this categorical distinction between humans and other organisms, we can learn to pay attention to and care for all manner of things, living and inert, that surround us at every moment in the cities in which we increasingly live. But this will only come about if we also nurture a very different kind of politics than that which now governs how cities are made (and unmade). We need a politics that, like the art displayed here, is a carefully wielded fine toothed comb rather than a blunt instrument of destruction.

Figs.x,xi

Lubaina Himid works in Preston and London and is Emeritus

Professor of Contemporary Art at the University of Central Lancashire. She is

the winner of the 2017 Turner Prize. Himid has exhibited extensively in the UK

and abroad. Significant solo exhibitions include Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern,

London (2021); Spotlights, Tate Britain, London (2019); The Grab Test, Frans

Hals Museum, Haarlem, The Netherlands (2019); Lubaina Himid, CAPC Bordeaux,

France (2019); Work From Underneath, New Museum, New York (2019); Gifts to

Kings, MRAC Languedoc Roussillon Midi-Pyrénées, Sérignan (2018); Our Kisses are

Petals, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead (2018); The Truth Is

Never Watertight, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe (2017); Navigation Charts,

Spike Island, Bristol (2017); and Invisible Strategies, Modern Art Oxford

(2017).

Paul Dobraszczyk is a Manchester-based writer and lecturer at the Bartlett School of Architecture, London. He's the author of many books, the most recent being Animal Architecture: Beasts, Buildings and Us(Reaktion, 2023) and Architecture and Anarchism: Building Without Authority (Paul Holberton, 2021) (as featured in recessed.space 007). He built the photographic website stonesofmanchester.com in 2018.

www.ragpickinghistory.co.uk

www.ragpickinghistory.co.uk

visit

A Fine Toothed Comb, curated by Lubaina Himid, is at HOME, Manchester, until 07January, 2024. Further details available at;

www.homemcr.org/exhibition/a-fine-toothed-comb-curated-by-lubaina-himid

images

fig.i Manchester skyline. © Will Jennings.

figs.ii,iii Rebecca Chesney, Cause and Effect (2023). © HOME, Manchester.

fig.iv Tracy Hill, Surgere (2023). © HOME, Manchester.

figs.v,vi Magda Stawarska, Music and Silence (2023). ©

HOME, Manchester.

fig.vii Rebecca Chesney, Red, Amber Green (2023). © Rebecca Chesney.

fig.viii Lubaina Himid, Kanga Door (2023). ©

HOME, Manchester.

fig.ix

Lubaina Himid, Undo the Knots of Poverty & Fire Brigade (2023). © HOME, Manchester.

fig.x

Lubaina Himid, Man in a Pyjama Drawer & Woman in a Creaking Drawer (2023). © HOME, Manchester.

fig.xi

Lubaina Himid, Fire Brigade (2023). © HOME, Manchester.

publication date

23 October 2023

tags

Birds, Birdsong, Rebecca Chesney, Cities, Mike Davis, Paul Dobraszczyk, Ecology, Friedrich Engels, Geology, Tracy Hill, Lubaina Himid, HOME, Karol Poznański Palace, Lithography, Łódź, Łódź library, Manchester, Painting, RSPB, Salford, Sculpture, Ian Simpson, Skyscraper, Magda Stawarska, Textile, Urban ecology, Textile, Tony Wilson

www.homemcr.org/exhibition/a-fine-toothed-comb-curated-by-lubaina-himid