RE/SISTERS: an expansive, but chaotic, exploration of gender & ecology

RE/SISTERS, the current exhibition at London’s Barbican

Gallery, seeks to explore the intersection of gender and ecology with a packed

exhibition of art, installation, and documentary. But perhaps, Nyima Murry wonders,

the sheer amount of work in the exhibition may detract from its curatorial messaging.

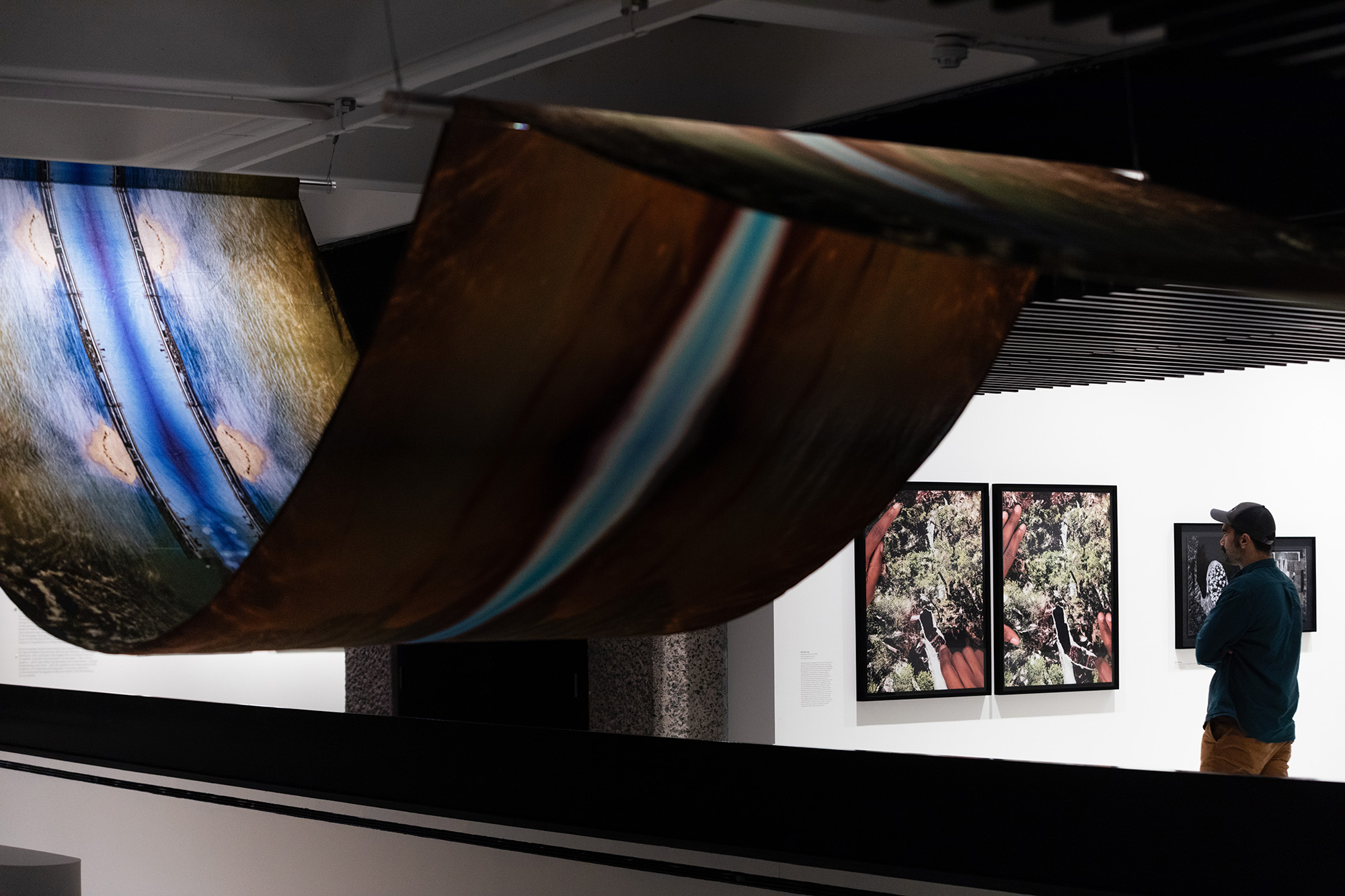

The Barbican’s latest major exhibition, RE/SISTERS: A

Lens on Gender and Ecology, brings together nearly fifty international

women and gender non-conforming artists whose work engages with – and protests

against – the ongoing ecological crisis. Whilst the ambition of the show is

both admirable and timely, working to demonstrate the relationship between

gender, environmental and social justice, the scale of the project overwhelms a

clear curatorial position.

The exhibited works include well works within the feminist art movement of the 1960s and 1970s, including Agnes Denes’s Wheatfield – A Confrontation (1982), for which she planted and harvested a wheatfield across a two-acre site close to Wall Street in New York to reclaim the land and celebrate earth’s generative potential. Barbara Kruger’s iconic collages also make an appearance, declaring We won’t play nature to your culture (1983), alongside photographs from Judy Chicago’s Atmospheres series that used pyrotechnics to soften environments in a unapologetically ‘feminine' way.

![]()

![]()

figs.i,ii

Although the show describes itself as looking to draw attention to the connections between gender and ecology to “identify the systemic links between the oppression of women and the degradation of the planet,” the exhibition works more successfully as a general resource than thorough interrogation of systemic oppression and environmental destruction that it claims. In part, this is because there is just a lot on show, with 250 works of photography, film, performance art, and installation filling both floors of the Barbican’s gallery. Links between the oppression of women and the degradation of the planet are complex, so to expect that such connections can be revealed across such an expansive show that jumps across space and time – projects are not curated geographically or chronologically – is a big ask of visitors.

The visitor’s task is only made more difficult through a lack of contextual information. Without any accompanying guide book to help navigate the artworks, the only supporting literature is a chunky (and rather pricey) book on offer in the giftshop at the end of the exhibition. The projects on display are only expanded on and contextualised in the rather cramped exhibition labels.

Expanding the definition of ‘ecology’ to consider it as co-constructed through material, spatial, social, and political concerns, the project is undeniably progressive and pertinent – it’s no longer enough to talk about environmental art as solely preoccupied with ‘sustainable’ or ‘green’ artwork. But by including so many different practices and responses to ecology, how gender fundamentally intersects with environmentalism has got somewhat lost, the show feeling more like an improv ‘yes and…’ brainstorm of how women and gender non-conforming artist have generally been practicing over the last century. This is not a critique of the artworks themselves – the photographic, film, and installation works from the 1960s onwards celebrate an incredible range of artistic practices.

![]()

![]()

figs.iii,iv

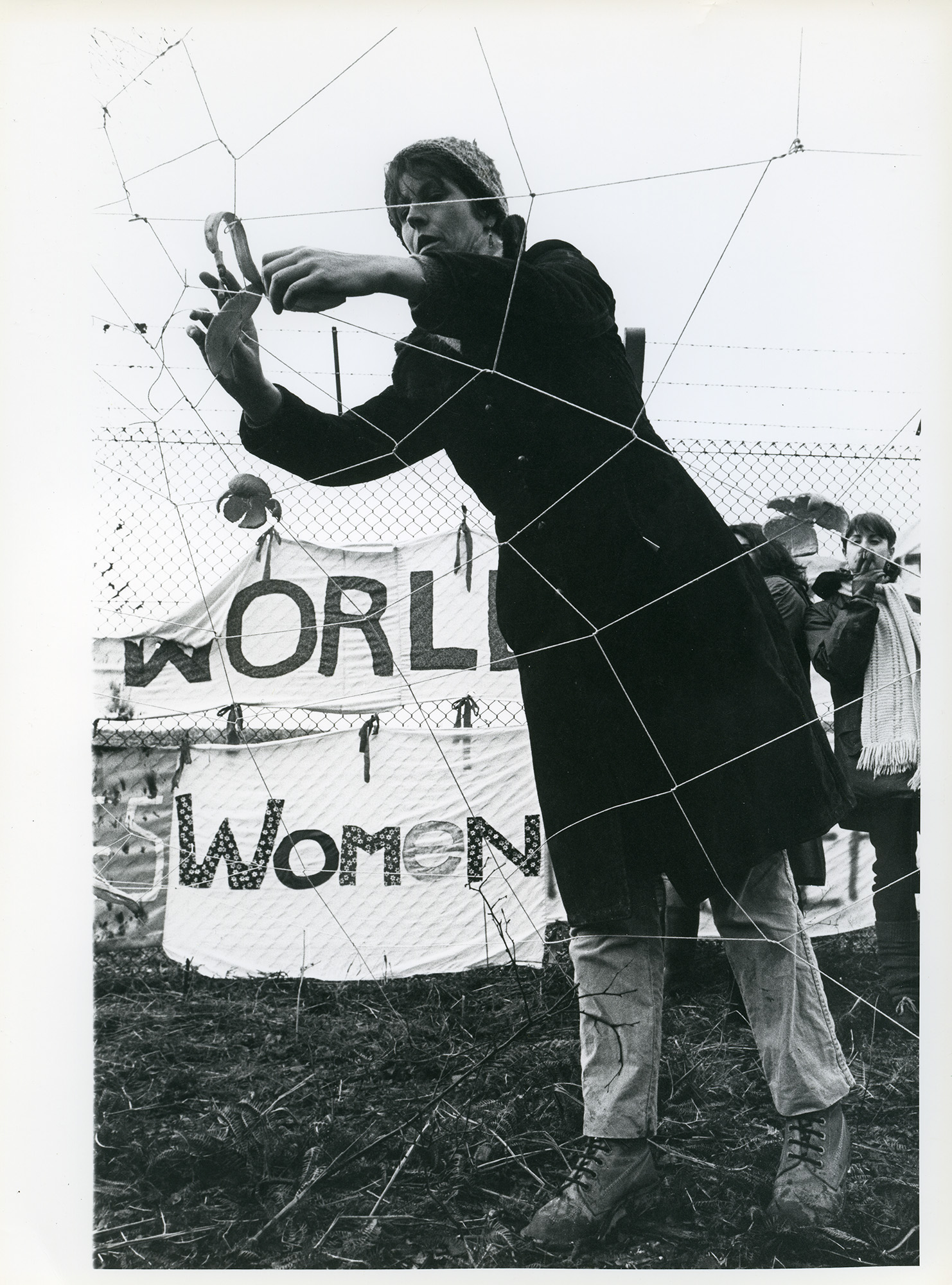

Archival imagery documenting the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp protest against nuclear weapons showcases its impact upon the wider nuclear disarmament movement. One of the longest-running peace camps in the world, lasting from 1981 until 2000, it began with an encircling of the RAF base and neighbouring ordnance factory with a human chain of nearly 70,000 people. The camp captured national attention, inspiring similar peace camps internationally.

A similar set of photographs exploring this women’s history in relation to ecology is currently on display a few miles up the road at the William Morris Gallery’s Radical Landscapes exhibition. Here though, the images are supported with textual information to help a visitor less familiar with the camp’s history understand the context to works on display – the William Morris curatorial team contextualising the peace camp within a wider narrative of people’s occupation and trespassing of British land, including an original Greenham banner and relating the images to a documentation of the 1932 mass trespass of Kinder Scout.

![]()

![]()

figs.v,vi

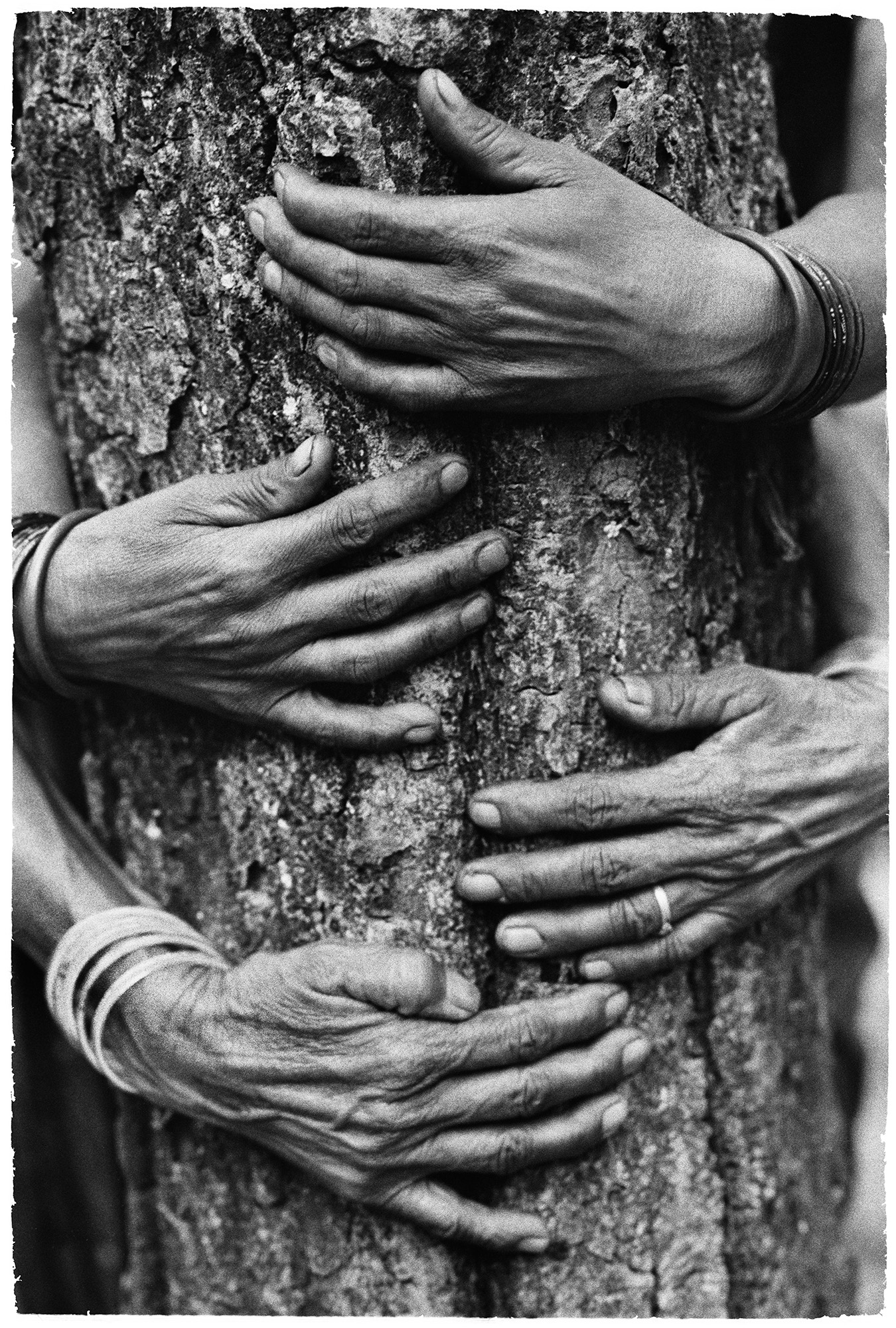

Interestingly at the Barbican, by displacing work from their contexts, new and unexpected connections are made between practices. Next to Greenham Common images made by Format, a women’s photography collective, are photographs of the Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas who used their bodies to prevent the felling of trees. Drawing connections between these two movements is undeniably beautiful, and it is refreshing to see the inclusion of a range of younger, and less internationally famous practitioners celebrated, many from the Global South. But the constant shift in location, time period, and specific contexts of works makes it difficult to follow.

In the neighbouring room, a film captures performance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles shaking hands with each of New York’s 8,500 Sanitation Department workers over the course of a year. Tough Sanitation draws attention to the often-thankless labour necessary to keep the city functioning, and whilst parallels can be made between such invisible public labour with invisible domestic labour performed by women, drawing out how the film contributes to the overall discussion of systemic oppression of women and the degradation of the planet could have been more successful.

![]()

![]()

figs.vii,viii

RE/SISTERS is accompanied by a series of public events which are perhaps the most thoughtful aspect of the exhibition. These have included a performance of protest songs inspired by Greenham Common, while contemporary performance artist Seyi Adelekun led a movement and embodiment workshop to heal ecological grief. A symposium in collaboration with the Paul Mellon Centre for British Art, Resist, Persist: Gender, Climate and Colonialism, explored the “indivisible bonds between gender and environmental justice” with a keynote from feminist-ecological Professor Astrida Neimanis, best known for her work around Hydrofeminism. In such programming, the crux of the complex intersection between eco-feminism, environmentalism, and imagining alternatives to colonial-capitalism found the necessary space to be thoughtfully digested where the exhibition felt cramped

![]()

![]()

figs.ix,x

After spending two hours, culminating in a rush through the final rooms, I awkwardly plop myself onto beanbags to watch Anne Duk Hee Jordan’s film installation Ziggy and the Starfish (2018), presenting hermaphroditic examples of aquatic life to draw playful parallels with non-binary identity and questions of gender. The surreal nature of the work and its contrast to the other artworks on display leaves me with less clarity on the intersecting relationship between gender and ecology than I thought I had upon arrival.

There is unequivocally a stark divide between who has caused – and continues to exacerbate – climate change with those who are suffering its increasingly catastrophic effects. I just wish this had been made more explicit throughout, if this was the driving ambition of the show. Instead, curatorial messages are muddled by the overall enthusiasm to summarise the breadth of how women and gender non-conforming artists and activists across the world have been working at the intersection of eco-feminism for decades. Perhaps, through identifying just how such work and ideas are not new, RE/SISTERS demonstrates the need for more exhibitions of this nature – just next time, maybe not including everything all at once.

The exhibited works include well works within the feminist art movement of the 1960s and 1970s, including Agnes Denes’s Wheatfield – A Confrontation (1982), for which she planted and harvested a wheatfield across a two-acre site close to Wall Street in New York to reclaim the land and celebrate earth’s generative potential. Barbara Kruger’s iconic collages also make an appearance, declaring We won’t play nature to your culture (1983), alongside photographs from Judy Chicago’s Atmospheres series that used pyrotechnics to soften environments in a unapologetically ‘feminine' way.

figs.i,ii

Although the show describes itself as looking to draw attention to the connections between gender and ecology to “identify the systemic links between the oppression of women and the degradation of the planet,” the exhibition works more successfully as a general resource than thorough interrogation of systemic oppression and environmental destruction that it claims. In part, this is because there is just a lot on show, with 250 works of photography, film, performance art, and installation filling both floors of the Barbican’s gallery. Links between the oppression of women and the degradation of the planet are complex, so to expect that such connections can be revealed across such an expansive show that jumps across space and time – projects are not curated geographically or chronologically – is a big ask of visitors.

The visitor’s task is only made more difficult through a lack of contextual information. Without any accompanying guide book to help navigate the artworks, the only supporting literature is a chunky (and rather pricey) book on offer in the giftshop at the end of the exhibition. The projects on display are only expanded on and contextualised in the rather cramped exhibition labels.

Expanding the definition of ‘ecology’ to consider it as co-constructed through material, spatial, social, and political concerns, the project is undeniably progressive and pertinent – it’s no longer enough to talk about environmental art as solely preoccupied with ‘sustainable’ or ‘green’ artwork. But by including so many different practices and responses to ecology, how gender fundamentally intersects with environmentalism has got somewhat lost, the show feeling more like an improv ‘yes and…’ brainstorm of how women and gender non-conforming artist have generally been practicing over the last century. This is not a critique of the artworks themselves – the photographic, film, and installation works from the 1960s onwards celebrate an incredible range of artistic practices.

figs.iii,iv

Archival imagery documenting the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp protest against nuclear weapons showcases its impact upon the wider nuclear disarmament movement. One of the longest-running peace camps in the world, lasting from 1981 until 2000, it began with an encircling of the RAF base and neighbouring ordnance factory with a human chain of nearly 70,000 people. The camp captured national attention, inspiring similar peace camps internationally.

A similar set of photographs exploring this women’s history in relation to ecology is currently on display a few miles up the road at the William Morris Gallery’s Radical Landscapes exhibition. Here though, the images are supported with textual information to help a visitor less familiar with the camp’s history understand the context to works on display – the William Morris curatorial team contextualising the peace camp within a wider narrative of people’s occupation and trespassing of British land, including an original Greenham banner and relating the images to a documentation of the 1932 mass trespass of Kinder Scout.

figs.v,vi

Interestingly at the Barbican, by displacing work from their contexts, new and unexpected connections are made between practices. Next to Greenham Common images made by Format, a women’s photography collective, are photographs of the Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas who used their bodies to prevent the felling of trees. Drawing connections between these two movements is undeniably beautiful, and it is refreshing to see the inclusion of a range of younger, and less internationally famous practitioners celebrated, many from the Global South. But the constant shift in location, time period, and specific contexts of works makes it difficult to follow.

In the neighbouring room, a film captures performance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles shaking hands with each of New York’s 8,500 Sanitation Department workers over the course of a year. Tough Sanitation draws attention to the often-thankless labour necessary to keep the city functioning, and whilst parallels can be made between such invisible public labour with invisible domestic labour performed by women, drawing out how the film contributes to the overall discussion of systemic oppression of women and the degradation of the planet could have been more successful.

figs.vii,viii

RE/SISTERS is accompanied by a series of public events which are perhaps the most thoughtful aspect of the exhibition. These have included a performance of protest songs inspired by Greenham Common, while contemporary performance artist Seyi Adelekun led a movement and embodiment workshop to heal ecological grief. A symposium in collaboration with the Paul Mellon Centre for British Art, Resist, Persist: Gender, Climate and Colonialism, explored the “indivisible bonds between gender and environmental justice” with a keynote from feminist-ecological Professor Astrida Neimanis, best known for her work around Hydrofeminism. In such programming, the crux of the complex intersection between eco-feminism, environmentalism, and imagining alternatives to colonial-capitalism found the necessary space to be thoughtfully digested where the exhibition felt cramped

figs.ix,x

After spending two hours, culminating in a rush through the final rooms, I awkwardly plop myself onto beanbags to watch Anne Duk Hee Jordan’s film installation Ziggy and the Starfish (2018), presenting hermaphroditic examples of aquatic life to draw playful parallels with non-binary identity and questions of gender. The surreal nature of the work and its contrast to the other artworks on display leaves me with less clarity on the intersecting relationship between gender and ecology than I thought I had upon arrival.

There is unequivocally a stark divide between who has caused – and continues to exacerbate – climate change with those who are suffering its increasingly catastrophic effects. I just wish this had been made more explicit throughout, if this was the driving ambition of the show. Instead, curatorial messages are muddled by the overall enthusiasm to summarise the breadth of how women and gender non-conforming artists and activists across the world have been working at the intersection of eco-feminism for decades. Perhaps, through identifying just how such work and ideas are not new, RE/SISTERS demonstrates the need for more exhibitions of this nature – just next time, maybe not including everything all at once.

Nyima

Murry is a British-Tibetan curator, design writer and filmmaker. Trained as a Landscape Architect, her work often deals with the intersection of art, architecture and landscape, reflecting the space in which her practice occupies. Nyima is a founding member of PATCH Collective, a BIPOC design collective who organise public events that engage with the built environment from the perspective of being of diaspora.

www.nyimamurry.com

visit

RE/SISTERS: A Lens of Gender and Ecology is at

Barbican Art Gallery until 14 January 2024. More information available at: www.barbican.org.uk/ReSisters

Radical Landscapes: Art inspired by the land is at William

Morris Gallery until 18 February.

More information available at: www.wmgallery.org.uk/event/radical-landscapes

images

figs.i,iv,v,vii-x Re/Sisters: A Lens on Gender and Ecology. Installation view, Barbican Art Gallery 5 Oct 2023 - 14 Jan 2024. © Jemima Yong / Barbican Art Gallery.

fig.ii Judy Chicago, Immolation from Women and Smoke, 1972. Fireworks performance Performed by Faith Wilding in the California Desert © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco.

fig.iii Maggie Murray, Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp - Embrace the Base action 12/12/1982, 1982 © Maggie Murray / Format Photographers Archive at Bishopsgate Institute Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute.

fig.vi Pamela Singh, Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas #74, 1994 © Pamela Singh Courtesy of sepiaEYE.

publication date

08 December 2023

tags

Seyi Adelekun, Barbican, Barbican Art Gallery, Judy Chicago, Chipko Tree Huggers, Curation, Agnes Denes, Ecology, Gender, Greenham Common, Anne Duk Hee Jordan, Kinder Scout, Barbara Kruger, Land, Nyima Murry, Astrida Neimanis, Nuclear, Peace Camp, Planet, Protest, Text, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, William Morris Gallery

Radical Landscapes: Art inspired by the land is at William Morris Gallery until 18 February. More information available at: www.wmgallery.org.uk/event/radical-landscapes