Humanise, by Thomas Heatherwick: a polemic against

brainwashed architects

Thomas Heatherwick, the designer behind London’s Coal Drops

Yard shopping centre, Cape Town’s Zeitz MOCAA art gallery, Shanghai’s mixed-use

1000 Trees, and the abandoned Garden Bridge, turns his creative eye to words

with new book Humanise. With a reach into a general audience most architects

could only dream of, Karrie Jacobs turns the pages to see if it makes

the perfect Christmas gift for the maker in your life.

As I near the end of Thomas Heatherwick’s physically imposing

but conceptually slender book, Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Designing Our Cities,

it dawns on that I should be the ideal reader – or, at least, a sympathetic

one.

After all, I was educated at a hippie college which had no majors, where written evaluations replaced numerical or letter grades, and where every course of study was supposed to be interdisciplinary. I write about architecture and design because it makes me appear to be a specialist when I am, in fact, a generalist. I should be cheering Heatherwick’s call for wresting control of building design from experts (who have screwed the world up so badly) and handing it over to artists and the “makers,” which is how Heatherwick defines himself.

![]()

![]()

fig.i, Thomas Heatherwick. fig.ii, The Vessel, by Heatherwick Studios

But here’s the catch. I am a New Yorker, living and working in close proximity to three completed Heatherwick projects. And New Yorkers – those of us who are not his billionaire clients, at least – tend to regard Heatherwick as punchline. After all, his most famous New York work is The Vessel, a 16-story tourist draw that the maker once described as a device that might allow us to reflect on what is “timeless about humans and our physicality.” The $200 million folly – and when I say folly, I don’t mean it just in the architectural sense – quickly became a magnet for suicides, tragically three in the space of a year, and with 154 flights of stairs and only token elevator access, it was also conspicuously hostile to those with disabilities. So, it’s a little hard for me to take Heatherwick seriously as a champion of humanity.

Humanise isn’t exactly about humanity, though. It’s a grandiose polemic against an argued plague of “boringness.” Specifically, Heatherwick is outraged that the world is full of rectilinear buildings. He contends that this is because the design of buildings, once the province of craftsmen (like Heatherwick!) was taken over by a cult of professionals known as architects. And architects – who he believes all worship at the church of Le Corbusier and are compelled at an impressionable age to read Derrida – have been systematically brainwashed into designing buildings that are mind-numbingly boring.

I am not oversimplifying. This is the point the book makes page after page after page.

![]()

![]()

To me, Humanise reads like a relic of my adolescence, when it might have made perfect sense. Back in the 1970s, urban renewal and corporate enthusiasms were filling the world with uninspired, knock-off Modernism. At the same time, there was a proliferation of books with loopy, unconventional narratives, all hippie-esque and charming: Abby Hoffman’s Steal This Bookand Richard Brautigan’s In Watermelon Sugar come to mind. If I had encountered Humanise back in my adolescence, when I knew very little about anything, I might have embraced it and taken his war against “boringness” to heart.

But it’s the 2020s, not the 1970s, and now an age when design software and computerised fabrication techniques have made swoopy, complex, decidedly non-rectilinear buildings much more commonplace. Also, I’ve done a little bit of reading since I was a teenager.

![]()

![]()

This boringness Heatherwick condemns – a plague that was, he argues, foisted upon us by Modernism, curtain walls, and brainwashed architects – is not exactly unexplored territory. Heatherwick the author, it turns out, is not more of an original thinker than all the dreary architects he detests.

For example, architect Robert Venturi (who was, apparently, not adequately brainwashed) wrote a book called Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, originally published in 1966, in which he stated: “Architects can no longer afford to be intimidated by the puritanically moral language of orthodox Modern architecture … I am for messy vitality over obvious unity.” In this single paragraph excerpt, Venturi says more than Heatherwick does over 500 pages – his succinct argument pushing against the rigidity of modernist orthodoxyends with a declaration: “More is not less.”

In her 1961 classic, The Death and Live of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs, who Heatherwick name checks in his endnotes, wrote of Le Corbusier: “His conception, as an architectural work, had a dazzling clarity, simplicity and harmony. It was so orderly, so visible, so easy to understand. It said everything in a flash, like a good advertisement.”

Jacobs takes Le Corbusier down in a heartbeat. Heatherwick, who I presume is writing for an audience who’s never heard of Le Corbusier, goes on and on about him for nearly 50 pages – though, granted, the type is very large and often triple or quadruple spaced. More than once I find myself asking: “Why Le Corb? Why now?”

![]()

![]()

Then there’s the Austrian artist turned architect, Friedrich Stowasser, better known as Hundertwasser, whose goofy, handcrafted buildings make him an obvious precursor to Heatherwick.

Hundertwasser’s 1958 Mouldiness Manifesto against Rationalism in Architecture argues that people should build and rebuild their own homes: “The apartment-house tenant must have the freedom to lean out of his window and as far as his arms can reach transform the exterior of his dwelling space … he must also be allowed to cut up the walls and make all kinds of changes, even if this disturbs the architectural harmony of a so-called masterwork…”

One could generously insist that the existence of all these earlier attempts to correct the rigidity of Modernist thinking tends to support Heatherwick’s thesis, such as it is a thesis at all. But the problem, for me at least, is that Heatherwick writes as he designs. He seems to believe that he is the first person to have had any given thought, whatever it is, and is so thoroughly charmed by himself that he doesn’t allow for the possibility that his standards of “boringness” and “interestingness” are not universal. And he hasn’t paused to realise that arguments that might work wonderfully in the context of sales pitch can’t necessarily sustain a book – although it’s pretty impressive that he manages to skim the surface for nearly 500 pages.

Frequently, to demonstrate that human beings really prefer curves over straight lines, or a variegated streetscape to a monolithic one, Heatherwick cites scientific studies. This is the worst of both worlds: a big ego bolstered by cherry-picked science.

On page 235 for example, Heatherwick writes that “Most studies” find residents of high-rise public housing developments are chronically unhappy. Here, he cites Robert Gifford, a professor of psychology and environmental studies – although he doesn’t think to mention where. Gifford, it seems, believes that high-rises are responsible for all sorts of pathologies and “may independently account for some suicides.” Imagine that…

![]()

![]()

The only truly readable sections of the book are a handful of brief autobiographical sketches. One is a 10-page narrative on the young Heatherwick’s education. His family background is interesting: His mum was a jewellery maker, while his grandmother worked for an architect, ur-Modernist Ernő Goldfinger. Heatherwick himself discovered Gaudi at age 18 – as so many of us did – before studying various types of design, then “made many kinds of different objects and experimented with everything that the tools, materials, and equipment could do.”

He also had occasion to attend educational programmes for would-be architects at which he discovered that his classmates didn’t know how to mix cement or weld as he could. Then he travelled Great Britain for his dissertation, researching “exactly what relationship designers of buildings had with making.” He mentions that he drove around the country in a Citroen filled with “watermelons as thank-you gifts for the people I met.” It is the single moment in the book that I find genuinely charming.

Almost 300 pages later, there’s another sliver of story-telling that goes a long way toward explaining the book’s hectoring quality: “About twenty-five years ago, a major competition was announced to design a contemporary art gallery. I wanted to enter this competition but because the entry requirements said you had to be a qualified architect; I wasn’t able to enter.”

What you’re meant to take away from these autobiographical snapshots is that Heatherwick’s education as a “maker” is richer and more varied than the backgrounds of all those woeful licensed specialists. They expose the roots of his animosity toward the profession, but the narrative sections suggest something else.

Heatherwick could have used his own story as the context for a book that addresses his issues with the built environment. Instead of a penning a relentless sales pitch, he could have written an honest book, making points that Venturi or Hundertwasser couldn’t possibly have made first. But an honest book demands an honest author.

![]()

![]()

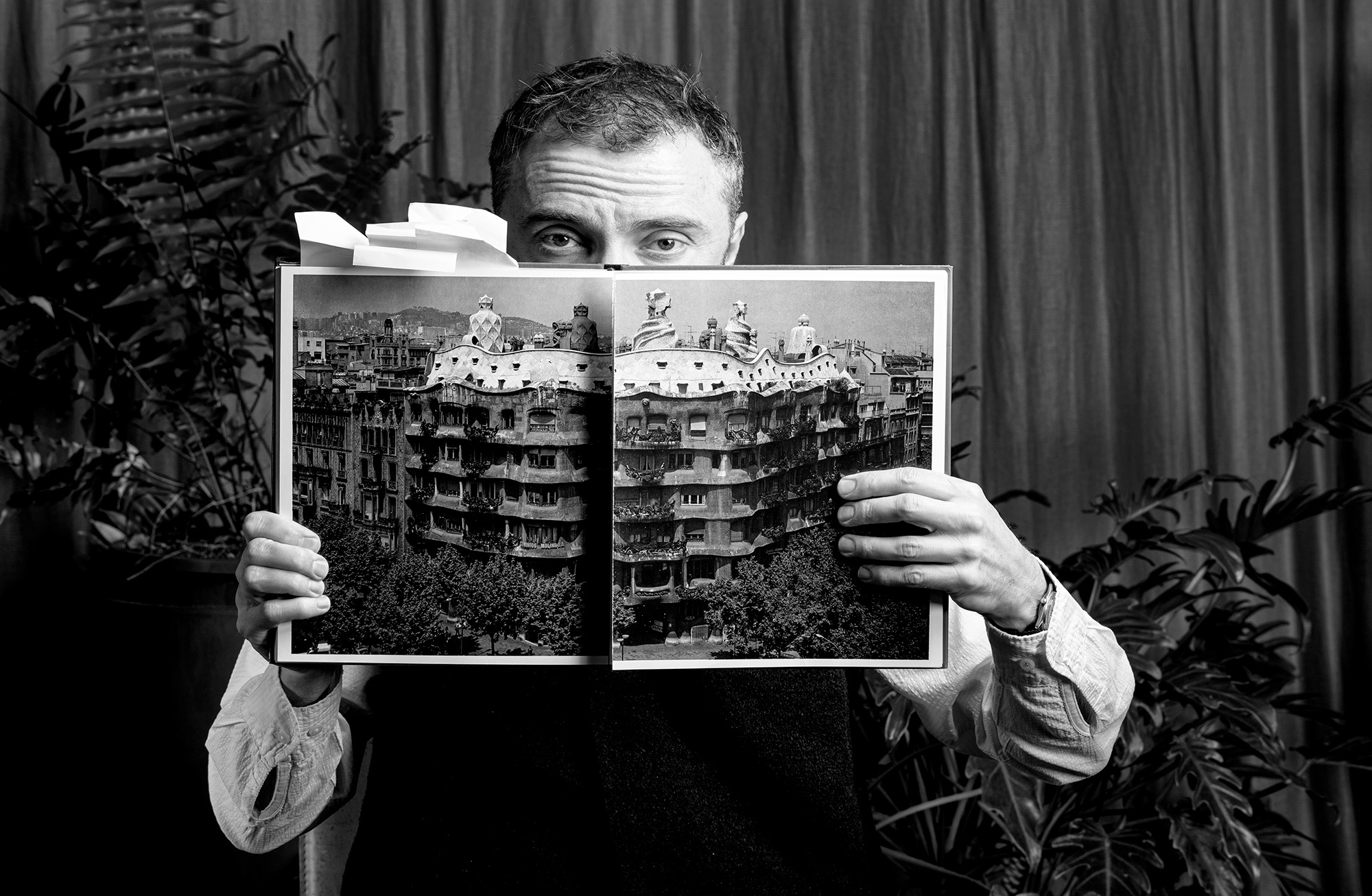

fig.xi, Humanise, by Thomas Heatherwick holding an image of Casa Mila by

Antoni Gaudí.

After all, I was educated at a hippie college which had no majors, where written evaluations replaced numerical or letter grades, and where every course of study was supposed to be interdisciplinary. I write about architecture and design because it makes me appear to be a specialist when I am, in fact, a generalist. I should be cheering Heatherwick’s call for wresting control of building design from experts (who have screwed the world up so badly) and handing it over to artists and the “makers,” which is how Heatherwick defines himself.

fig.i, Thomas Heatherwick. fig.ii, The Vessel, by Heatherwick Studios

But here’s the catch. I am a New Yorker, living and working in close proximity to three completed Heatherwick projects. And New Yorkers – those of us who are not his billionaire clients, at least – tend to regard Heatherwick as punchline. After all, his most famous New York work is The Vessel, a 16-story tourist draw that the maker once described as a device that might allow us to reflect on what is “timeless about humans and our physicality.” The $200 million folly – and when I say folly, I don’t mean it just in the architectural sense – quickly became a magnet for suicides, tragically three in the space of a year, and with 154 flights of stairs and only token elevator access, it was also conspicuously hostile to those with disabilities. So, it’s a little hard for me to take Heatherwick seriously as a champion of humanity.

Humanise isn’t exactly about humanity, though. It’s a grandiose polemic against an argued plague of “boringness.” Specifically, Heatherwick is outraged that the world is full of rectilinear buildings. He contends that this is because the design of buildings, once the province of craftsmen (like Heatherwick!) was taken over by a cult of professionals known as architects. And architects – who he believes all worship at the church of Le Corbusier and are compelled at an impressionable age to read Derrida – have been systematically brainwashed into designing buildings that are mind-numbingly boring.

I am not oversimplifying. This is the point the book makes page after page after page.

fig.iii, Little Island, by Heatherwick Studios. fig.iv, Mill Owner's Association Building, by Le Corbusier.

To me, Humanise reads like a relic of my adolescence, when it might have made perfect sense. Back in the 1970s, urban renewal and corporate enthusiasms were filling the world with uninspired, knock-off Modernism. At the same time, there was a proliferation of books with loopy, unconventional narratives, all hippie-esque and charming: Abby Hoffman’s Steal This Bookand Richard Brautigan’s In Watermelon Sugar come to mind. If I had encountered Humanise back in my adolescence, when I knew very little about anything, I might have embraced it and taken his war against “boringness” to heart.

But it’s the 2020s, not the 1970s, and now an age when design software and computerised fabrication techniques have made swoopy, complex, decidedly non-rectilinear buildings much more commonplace. Also, I’ve done a little bit of reading since I was a teenager.

fig.v, Google HQ, by Heatherwick Studio. fig.vi, Unité d'Habitation Berlin, by Le Corbusier.

This boringness Heatherwick condemns – a plague that was, he argues, foisted upon us by Modernism, curtain walls, and brainwashed architects – is not exactly unexplored territory. Heatherwick the author, it turns out, is not more of an original thinker than all the dreary architects he detests.

For example, architect Robert Venturi (who was, apparently, not adequately brainwashed) wrote a book called Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, originally published in 1966, in which he stated: “Architects can no longer afford to be intimidated by the puritanically moral language of orthodox Modern architecture … I am for messy vitality over obvious unity.” In this single paragraph excerpt, Venturi says more than Heatherwick does over 500 pages – his succinct argument pushing against the rigidity of modernist orthodoxyends with a declaration: “More is not less.”

In her 1961 classic, The Death and Live of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs, who Heatherwick name checks in his endnotes, wrote of Le Corbusier: “His conception, as an architectural work, had a dazzling clarity, simplicity and harmony. It was so orderly, so visible, so easy to understand. It said everything in a flash, like a good advertisement.”

Jacobs takes Le Corbusier down in a heartbeat. Heatherwick, who I presume is writing for an audience who’s never heard of Le Corbusier, goes on and on about him for nearly 50 pages – though, granted, the type is very large and often triple or quadruple spaced. More than once I find myself asking: “Why Le Corb? Why now?”

fig.vii, Hundertwasser House, by Friedrich Hundertwasser. viii, 1000 Trees, by Heatherwick Studio.

Then there’s the Austrian artist turned architect, Friedrich Stowasser, better known as Hundertwasser, whose goofy, handcrafted buildings make him an obvious precursor to Heatherwick.

Hundertwasser’s 1958 Mouldiness Manifesto against Rationalism in Architecture argues that people should build and rebuild their own homes: “The apartment-house tenant must have the freedom to lean out of his window and as far as his arms can reach transform the exterior of his dwelling space … he must also be allowed to cut up the walls and make all kinds of changes, even if this disturbs the architectural harmony of a so-called masterwork…”

One could generously insist that the existence of all these earlier attempts to correct the rigidity of Modernist thinking tends to support Heatherwick’s thesis, such as it is a thesis at all. But the problem, for me at least, is that Heatherwick writes as he designs. He seems to believe that he is the first person to have had any given thought, whatever it is, and is so thoroughly charmed by himself that he doesn’t allow for the possibility that his standards of “boringness” and “interestingness” are not universal. And he hasn’t paused to realise that arguments that might work wonderfully in the context of sales pitch can’t necessarily sustain a book – although it’s pretty impressive that he manages to skim the surface for nearly 500 pages.

Frequently, to demonstrate that human beings really prefer curves over straight lines, or a variegated streetscape to a monolithic one, Heatherwick cites scientific studies. This is the worst of both worlds: a big ego bolstered by cherry-picked science.

On page 235 for example, Heatherwick writes that “Most studies” find residents of high-rise public housing developments are chronically unhappy. Here, he cites Robert Gifford, a professor of psychology and environmental studies – although he doesn’t think to mention where. Gifford, it seems, believes that high-rises are responsible for all sorts of pathologies and “may independently account for some suicides.” Imagine that…

fig.ix, Coal Drops Yard, by Heatherwick Studio. fig.x, Casa Batlló, by Antoni Gaudí.

The only truly readable sections of the book are a handful of brief autobiographical sketches. One is a 10-page narrative on the young Heatherwick’s education. His family background is interesting: His mum was a jewellery maker, while his grandmother worked for an architect, ur-Modernist Ernő Goldfinger. Heatherwick himself discovered Gaudi at age 18 – as so many of us did – before studying various types of design, then “made many kinds of different objects and experimented with everything that the tools, materials, and equipment could do.”

He also had occasion to attend educational programmes for would-be architects at which he discovered that his classmates didn’t know how to mix cement or weld as he could. Then he travelled Great Britain for his dissertation, researching “exactly what relationship designers of buildings had with making.” He mentions that he drove around the country in a Citroen filled with “watermelons as thank-you gifts for the people I met.” It is the single moment in the book that I find genuinely charming.

Almost 300 pages later, there’s another sliver of story-telling that goes a long way toward explaining the book’s hectoring quality: “About twenty-five years ago, a major competition was announced to design a contemporary art gallery. I wanted to enter this competition but because the entry requirements said you had to be a qualified architect; I wasn’t able to enter.”

What you’re meant to take away from these autobiographical snapshots is that Heatherwick’s education as a “maker” is richer and more varied than the backgrounds of all those woeful licensed specialists. They expose the roots of his animosity toward the profession, but the narrative sections suggest something else.

Heatherwick could have used his own story as the context for a book that addresses his issues with the built environment. Instead of a penning a relentless sales pitch, he could have written an honest book, making points that Venturi or Hundertwasser couldn’t possibly have made first. But an honest book demands an honest author.

fig.xi, Humanise, by Thomas Heatherwick holding an image of Casa Mila by

Antoni Gaudí.

Karrie Jacobs is a professional observer of the manmade

landscape.

She writes for Curbed, the New York Review of Architecture and, every now and then, the New York Times. Karrie is a faculty

member at the School of Visual Arts’ MA program in Design Research, Writing,

and Criticism, where she teaches students how to understand and interpret the

design-rich environment all around them. She was the founding editor-in-chief

of Dwell and the founding executive editor of Benetton's Colors. She is the

author of The Perfect $100,000 House (2006) and coauthor of Angry Graphics

(1992).

www.karriejacobs.com

Thomas Heatherwick is one of the world's most prolific

designers, whose varied work over two decades is characterised by its

originality, inventiveness and humanity. Defying conventional classifications,

Heatherwick founded his studio in 1994 to bring together architecture, urban

planning, product design and interiors into a single creative workspace. Led by

human experience rather than any fixed dogma, the studio creates emotionally

compelling places and objects with the smallest possible carbon footprint.

From their base in London, Heatherwick's team is currently

working on over thirty projects in ten countries, including Toranomon-Azabudai,

a six-hectare mixed-use development in the centre of Tokyo, the new

headquarters for Google in London and Airo, an electric car that cleans the air

as it drives.

The studio has also recently completed Bay View,

Google's first ground-up campus and Little Island, a park and performance space

on the Hudson River in New York as well as the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art

Africa in Cape Town; and Coal Drops Yard, a major new retail district in King's

Cross, London.

www.heatherwick.com

From their base in London, Heatherwick's team is currently working on over thirty projects in ten countries, including Toranomon-Azabudai, a six-hectare mixed-use development in the centre of Tokyo, the new headquarters for Google in London and Airo, an electric car that cleans the air as it drives.

The studio has also recently completed Bay View, Google's first ground-up campus and Little Island, a park and performance space on the Hudson River in New York as well as the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town; and Coal Drops Yard, a major new retail district in King's Cross, London.

www.heatherwick.com