Middlesbrough Art Week created an exhilarating transformation

of the town centre

With its 7th edition just having completed, this

year’s Middlesbrough Art Week transformed the high street & shopping

centres of the town into a vast art gallery. Organised by local artist-led

organisation The Auxiliary Project Space, turning empty shops turned into

experimental cultural spaces, Jonathan McAloon visited to discover a special

connection between the local cultural scene & the everyday urban bustle.

The German critic Walter Benjamin spent the last years of

his life on a sprawling unfinished work now known as The Arcades

Project. Among other things, it argued that the height of 19th-century

Parisian culture, centred around its newly constructed department stores and

indoor shopping arcades, was made possible by the iron industry.

Across the Channel during that heyday, the young North Yorkshire town of Middlesbrough was growing rich as an iron manufacturing capital, attracting famous Gothic-Revival architects to design its churches and civic buildings. Much has changed since then and due to the current economic climate – as is the case up and down the country – many of its high street shops have closed.

Across the Channel during that heyday, the young North Yorkshire town of Middlesbrough was growing rich as an iron manufacturing capital, attracting famous Gothic-Revival architects to design its churches and civic buildings. Much has changed since then and due to the current economic climate – as is the case up and down the country – many of its high street shops have closed.

But Middlesbrough has come up with a novel solution, with arts organisations and charities leasing empty shopping units to turn them into pop-up galleries or studio spaces (see also Hypha Studios, 00137) with many all over town, all explorable for the annual art week overseen by a team led yb Artistic Director Liam Slevin and directors Anna Byrne and Edel O’Reilly. Other works – including Words per Minute, a temporary information sign presenting statements selected from an open-call – take over the streets.

The result is something special and exhilarating: very little separation between the bustle of daily life and the cultural scene. As I wandered around the town and its four linked shopping arcades during MAW I felt a spirit that might have appealed to Walter Benjamin, a writer who considered all forms of material culture with the same rigour and wonder.

NORTH EAST OPEN CALL

As you enter the Cleveland Centre shopping arcade, a larger-than-life paper aeroplane, made out of plywood, sits quite unobtrusively in the main thoroughfare surrounded by working stalls and shopfronts. It’s an image universal enough not to unsettle passersby, while also letting them know that something is going on. And, hopefully, draw them into it.

This is Matthew Young’s Mood Bored, a work of sculpture from MAW’s North East Open Call show, which is a few shopfronts along. A large retail space that used to be a Poundland has been given over to eight of the two hundred or so artists who responded to the call. Near the front are the ceramics of Christine Walker. She packages her works – which incorporate reclaimed industrial slag from the surrounding area into their clay and have titles like Munter – as self-consciously ugly, seeking to interrogate modern perceptions of beauty. Though Walker’s rich corals and aquamarines, and the high finish of the glaze on these knobbled forms, is beautiful by whatever beauty standards might be interrogated.

There’s a powerful strand of reclaimed materials throughout not just this selection, but the wider MAW offering. In the middle of the room, Chris Thompson’s The Vessel, an interactive installation where a cabinet’s draws pour out light and polyphonic choral music like some sort of video game treasure chest, has been constructed out of parquet flooring from local council estates. Thompson, a set designer for the Donmar Warehouse, has been inspired by historic museum collections carelessly and at times violently brought together by figures such as Sir John Soane, whose party guests would use Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi as drinks tables.

As you enter the Cleveland Centre shopping arcade, a larger-than-life paper aeroplane, made out of plywood, sits quite unobtrusively in the main thoroughfare surrounded by working stalls and shopfronts. It’s an image universal enough not to unsettle passersby, while also letting them know that something is going on. And, hopefully, draw them into it.

This is Matthew Young’s Mood Bored, a work of sculpture from MAW’s North East Open Call show, which is a few shopfronts along. A large retail space that used to be a Poundland has been given over to eight of the two hundred or so artists who responded to the call. Near the front are the ceramics of Christine Walker. She packages her works – which incorporate reclaimed industrial slag from the surrounding area into their clay and have titles like Munter – as self-consciously ugly, seeking to interrogate modern perceptions of beauty. Though Walker’s rich corals and aquamarines, and the high finish of the glaze on these knobbled forms, is beautiful by whatever beauty standards might be interrogated.

There’s a powerful strand of reclaimed materials throughout not just this selection, but the wider MAW offering. In the middle of the room, Chris Thompson’s The Vessel, an interactive installation where a cabinet’s draws pour out light and polyphonic choral music like some sort of video game treasure chest, has been constructed out of parquet flooring from local council estates. Thompson, a set designer for the Donmar Warehouse, has been inspired by historic museum collections carelessly and at times violently brought together by figures such as Sir John Soane, whose party guests would use Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi as drinks tables.

THIS WAS A MOSQUE

In a previous online digital exhibition, Alia Gargum recreated her grandmother’s home in 1980s Libya. Now, in 41 Dundas Street, the artist recreates this recreation: a space which only exists in memory, engaging with ideas of forced migration and involving research into the lives of exiles from North African regions and the Middle East.

Cloth of deep green is hung, twisted, around the gallery walls, or around steel rods. As well as a sacred colour in Islam, green was synonymous with Muammar Gaddafi’s dictatorship: his The Green Book, which laid out his political thought, being an answer to Chairman Mao’s The Little Red Book. The exhibition has been curated so that this green is constantly offset by the russets of wood and rusted steel. And as these pieces of steel have moved through time, acquiring a Verdigris layer of oxidation, the palette returns to green.

Again, many of the materials Gargum uses here are reclaimed, whether from her own previous work in steel, or pews discarded during the refurbishment of a Stockton church. Cut up, these pews have been arranged in a motif of interlocking rectangles familiar in Islamic art and the work of Arab Optical artists in the 1960s.

In a previous online digital exhibition, Alia Gargum recreated her grandmother’s home in 1980s Libya. Now, in 41 Dundas Street, the artist recreates this recreation: a space which only exists in memory, engaging with ideas of forced migration and involving research into the lives of exiles from North African regions and the Middle East.

Cloth of deep green is hung, twisted, around the gallery walls, or around steel rods. As well as a sacred colour in Islam, green was synonymous with Muammar Gaddafi’s dictatorship: his The Green Book, which laid out his political thought, being an answer to Chairman Mao’s The Little Red Book. The exhibition has been curated so that this green is constantly offset by the russets of wood and rusted steel. And as these pieces of steel have moved through time, acquiring a Verdigris layer of oxidation, the palette returns to green.

Again, many of the materials Gargum uses here are reclaimed, whether from her own previous work in steel, or pews discarded during the refurbishment of a Stockton church. Cut up, these pews have been arranged in a motif of interlocking rectangles familiar in Islamic art and the work of Arab Optical artists in the 1960s.

NOT ALLOWED FOR ALGORITHMIC AUDIENCES

Through the window of a shopping unit, a large screen displays the bald head and shoulders of a CGI character. It is a virtual assistant, the graphics are smooth but, we notice, not quite cutting-edge. The face blinks as if glitching. And when, entering Unit 11 of the Cleveland Centre, we hear speech in a stiff voice, the character considers their own obsolescence.

This is an installation by the Greek multimedia artist Kyriaki Goni, which she completed for her 2021 ARS Electronica ArtScience residency. Goni’s work has previously explored ecology, space travel, and hybrid forms of plant and human intelligence. And as this work’s 3D avatar tells us about the extraction of rare earth metals, the “geology of deep time” and the history of machines like her, they confess to sometimes dreaming of “dark mines, radioactive waste”. We get a sense of this soon-to-be-retired artificial intelligence is only just coming to a sense of themselves. And perhaps using a newfound self-awareness to play with the narrative, to mislead the viewer, too.

Through the window of a shopping unit, a large screen displays the bald head and shoulders of a CGI character. It is a virtual assistant, the graphics are smooth but, we notice, not quite cutting-edge. The face blinks as if glitching. And when, entering Unit 11 of the Cleveland Centre, we hear speech in a stiff voice, the character considers their own obsolescence.

This is an installation by the Greek multimedia artist Kyriaki Goni, which she completed for her 2021 ARS Electronica ArtScience residency. Goni’s work has previously explored ecology, space travel, and hybrid forms of plant and human intelligence. And as this work’s 3D avatar tells us about the extraction of rare earth metals, the “geology of deep time” and the history of machines like her, they confess to sometimes dreaming of “dark mines, radioactive waste”. We get a sense of this soon-to-be-retired artificial intelligence is only just coming to a sense of themselves. And perhaps using a newfound self-awareness to play with the narrative, to mislead the viewer, too.

NIGHT FISHING WITH ANCESTORS

Middlesbrough’s Captain Cook Square was named for one of Teesside’s most influential exports when it opened in 1999. The council’s recent, tentative plans to rename the shopping centre met with local backlash, and have since been shelved. But an art space in what used to be the centre’s Ladbrokes is staging a subversion.

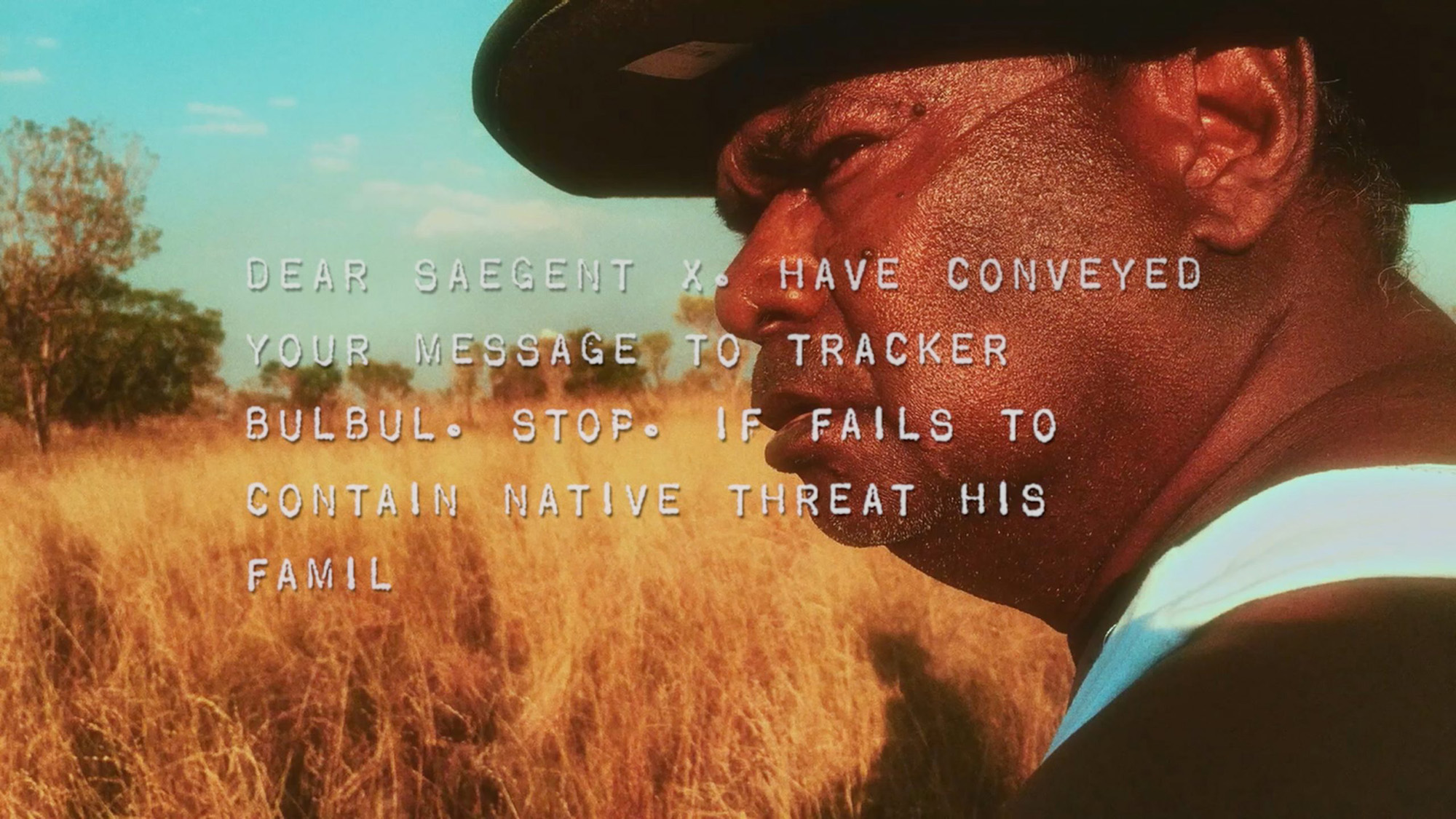

Night Fishing with Ancestors is a piece of video art made by the Karrabing Film Collective: an indigenous Australian filmmaking group. It begins by telling the story of the Macassans: Indonesian traders who came peacefully to Australia in the 18th century to collect sea cucumbers. Then when Europeans arrive, we know the rest.

Karrabing use a mixture of silent film intertitles, documentary interviews and Brechtian dramatic scenes to reimagine Australia’s violent history of colonisation. But the most powerful effect is a simple bit of wordplay: the distance between the peaceful Macassans, and the white people who “massacred” everyone who wouldn’t make a deal with them.

Middlesbrough’s Captain Cook Square was named for one of Teesside’s most influential exports when it opened in 1999. The council’s recent, tentative plans to rename the shopping centre met with local backlash, and have since been shelved. But an art space in what used to be the centre’s Ladbrokes is staging a subversion.

Night Fishing with Ancestors is a piece of video art made by the Karrabing Film Collective: an indigenous Australian filmmaking group. It begins by telling the story of the Macassans: Indonesian traders who came peacefully to Australia in the 18th century to collect sea cucumbers. Then when Europeans arrive, we know the rest.

Karrabing use a mixture of silent film intertitles, documentary interviews and Brechtian dramatic scenes to reimagine Australia’s violent history of colonisation. But the most powerful effect is a simple bit of wordplay: the distance between the peaceful Macassans, and the white people who “massacred” everyone who wouldn’t make a deal with them.

ON THE MOVE

Even upon arriving into Middlesbrough, orange and beige train tickets hang above you in ropes. Something that perversely reminded me of skeletal mounts we might see in the atria of natural history museums. This is Beth Johnson’s sculpture Journey, part of MAW’s Most Creative Station, an exhibition of site-specific works. Then as you walk around the town, you don’t need to enter gallery spaces to encounter work.

Olana Light’s Birch Tree Family installation can be seen behind shopping arcade glass: three uncanny hybrid forms of human legs topped by the trunks of trees. But around the town, Light might be seen embodying one of these birch tree forms in promenade herself, as her practice has living sculpture elements. Themes of ecology and interspecies entanglement are strongly represented at MAW.

Amy Dover spends hours on painstaking pencil drawings of endangered creatures, then invites viewers to erase them. In the case of You can’t bury what is lost, when the world grows smaller, members of the public passing through the Hillstreet Shopping Centre will be asked to rub out a beautiful bison that has taken hours and hours to draw, mirroring the animal’s disappearance all over Europe before reintroduction efforts.

People experiencing Dover’s work in the past have had dramatic, distressed reactions to watching her works being erased, or to performing this erasure themselves. The destruction of something that required so much time feels a dreadful loss. The proposition is: if you feel this for hours of human work, what is the appropriate feeling for the species themselves, who have taken millions of years of evolutionary time to arrive?

Even upon arriving into Middlesbrough, orange and beige train tickets hang above you in ropes. Something that perversely reminded me of skeletal mounts we might see in the atria of natural history museums. This is Beth Johnson’s sculpture Journey, part of MAW’s Most Creative Station, an exhibition of site-specific works. Then as you walk around the town, you don’t need to enter gallery spaces to encounter work.

Olana Light’s Birch Tree Family installation can be seen behind shopping arcade glass: three uncanny hybrid forms of human legs topped by the trunks of trees. But around the town, Light might be seen embodying one of these birch tree forms in promenade herself, as her practice has living sculpture elements. Themes of ecology and interspecies entanglement are strongly represented at MAW.

Amy Dover spends hours on painstaking pencil drawings of endangered creatures, then invites viewers to erase them. In the case of You can’t bury what is lost, when the world grows smaller, members of the public passing through the Hillstreet Shopping Centre will be asked to rub out a beautiful bison that has taken hours and hours to draw, mirroring the animal’s disappearance all over Europe before reintroduction efforts.

People experiencing Dover’s work in the past have had dramatic, distressed reactions to watching her works being erased, or to performing this erasure themselves. The destruction of something that required so much time feels a dreadful loss. The proposition is: if you feel this for hours of human work, what is the appropriate feeling for the species themselves, who have taken millions of years of evolutionary time to arrive?

PINEAPPLE BLACK

There has been a long engagement between Middlesbrough’s arts community and the large migrant community concentrated in the area. Pineapple Black, a gallery and cultural venue in a large, vacated shopping unit that used to be New Look, hosts UPROOT Collective, who throughout the year have planted various small meadows around town - sometimes only the size of a car parking space - with children and community groups. These modular meadows have been united indoors, arranged around a space that caters to families. The beds are wild, a bit shabby, alive, and designed by garden designer Kathryn Feeley. Insects buzz around them, and visitors will be encouraged to take their seeds.

As well hosting various workshops and speakers, Pineapple Black also screens Francis Alÿs’ film The Silence of Ani, whose sounds of birdsong – and the mimicry of this by a group of Armenian children with reeds, whistles recorders and other small instruments – bleeds into the environment created by UPROOT’s meadow.

In August this year, after the Southport stabbings, Middlesbrough became a site for racist anti-migrant rioting. The result was over a hundred arrests and thousands of pounds of criminal damage to the town centre, including to Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, with a masked group smashing the museum’s windows. In the wake of this, the work of organisations and support networks like those hosted at Pineapple Black feel essential.

There has been a long engagement between Middlesbrough’s arts community and the large migrant community concentrated in the area. Pineapple Black, a gallery and cultural venue in a large, vacated shopping unit that used to be New Look, hosts UPROOT Collective, who throughout the year have planted various small meadows around town - sometimes only the size of a car parking space - with children and community groups. These modular meadows have been united indoors, arranged around a space that caters to families. The beds are wild, a bit shabby, alive, and designed by garden designer Kathryn Feeley. Insects buzz around them, and visitors will be encouraged to take their seeds.

As well hosting various workshops and speakers, Pineapple Black also screens Francis Alÿs’ film The Silence of Ani, whose sounds of birdsong – and the mimicry of this by a group of Armenian children with reeds, whistles recorders and other small instruments – bleeds into the environment created by UPROOT’s meadow.

In August this year, after the Southport stabbings, Middlesbrough became a site for racist anti-migrant rioting. The result was over a hundred arrests and thousands of pounds of criminal damage to the town centre, including to Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, with a masked group smashing the museum’s windows. In the wake of this, the work of organisations and support networks like those hosted at Pineapple Black feel essential.

INSTITUTIONS & HERITAGE

MIMA remains the town’s flagship cultural attraction, and since opening in 2007 has continued to acquire high-quality contemporary pieces as they are produced, sometimes beating the likes of Oprah Winfrey to a buy. Recent exhibitions include a retrospective of Jacqueline Poncelet (see 00174) and the current show, Towards New Worlds, showcases multi-sensory work by 15 disabled, deaf, or neurodiverse practitioners. A highlight is Christopher Samuel’s The Archive of An Unseen (2022), where the viewer sits in a corner of the gallery that has been decorated with geometric patterns. There, on a 1980s computer monitor, they navigate their way through the artist’s youth and adolescence.

Various architectural legacies jostle each other in Middlesbrough. Gothic Revival buildings from the town’s Victorian heyday, such as G. G Hoskin’s Gothic Town Hall, is next to the turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau Empire nightclub, where Charlie Chaplin performed. St Columba’s church by Temple Moore, one of the most famous Gothic Revival Architects, stands, almost elongated, on a butt of land between roads near the shopping arcades. Much of Middlesbrough’s mid-century architecture has been or are is in the process of being knocked down, but many nonetheless cherished in some capacity by its inhabitants.

MIMA remains the town’s flagship cultural attraction, and since opening in 2007 has continued to acquire high-quality contemporary pieces as they are produced, sometimes beating the likes of Oprah Winfrey to a buy. Recent exhibitions include a retrospective of Jacqueline Poncelet (see 00174) and the current show, Towards New Worlds, showcases multi-sensory work by 15 disabled, deaf, or neurodiverse practitioners. A highlight is Christopher Samuel’s The Archive of An Unseen (2022), where the viewer sits in a corner of the gallery that has been decorated with geometric patterns. There, on a 1980s computer monitor, they navigate their way through the artist’s youth and adolescence.

Various architectural legacies jostle each other in Middlesbrough. Gothic Revival buildings from the town’s Victorian heyday, such as G. G Hoskin’s Gothic Town Hall, is next to the turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau Empire nightclub, where Charlie Chaplin performed. St Columba’s church by Temple Moore, one of the most famous Gothic Revival Architects, stands, almost elongated, on a butt of land between roads near the shopping arcades. Much of Middlesbrough’s mid-century architecture has been or are is in the process of being knocked down, but many nonetheless cherished in some capacity by its inhabitants.

Nowhere better exemplifies this mix than the vicinity of

MIMA, where across the way, the crumbling Civic Centre on Dunning Street is

marked for demolition. But this imposing structure – its protruding

three-tiered concrete overhang with rounded lozenge shaped recesses, its tinted

glass – is aesthetically interesting in its own right: a fine example of

Corporate Brutalism which could surely be made to suit another purpose.

In this part of the town, remnants of a difficult 20th-century coexist with the town’s aspirational cultural future, and aspirational Romanesque past.

In this part of the town, remnants of a difficult 20th-century coexist with the town’s aspirational cultural future, and aspirational Romanesque past.

Middlesbrough Art Week has just presenting its 7th festival edition, taking place across the town from Thursday 26 September to Saturday 05 October, 2024. Born in 2017 as an artist-led festival powered by The Auxiliary Project Space, a small growing team of artists, curators and coordinators, and fuelled by wide reaching partnerships. MAW supports artist ecologies in the North East, connecting artistic practice and ideas with like-minded peers nationally and internationally, and is committed to practice and not just preach principles of fair work and social justice.

Over the years artists have been invited to make the Transporter Bridge sing, install a giant drawing ball at Middlesbrough Town Hall, bring a dystopian model village to Centre Square, turn Church House into a beating heart, an old bank into an art gallery, and fly a giant inflatable pig in from Japan.

www.middlesbroughartweek.com

The Auxiliary Project Space is an artist-led National Portfolio Organisation. Based in a 11,000 sq ft warehouse including artist studios, exhibition and workshop space, it emphasises artistic development, large scale exhibitions and community participation. The Auxiliary will undergo a major refurbishment in May 2024, thanks to the DCMS Cultural Development Fund and Mayoral Development Fund.

www.theauxiliary.co.uk

Jonathan McAloon is an arts journalist and book critic. He has written for the FT, BBC, Guardian, Irish Times, Telegraph, Elephant and i-D, among others.

www.theauxiliary.co.uk

Jonathan McAloon is an arts journalist and book critic. He has written for the FT, BBC, Guardian, Irish Times, Telegraph, Elephant and i-D, among others.

more information

While Middlesbrough Art Week 2024 has concluded, you can visit

their website to find out much more on the exhibiting artists as well as save

it to check back ahead of next year’s edition:

middlesbroughartweek.com

Towards New Worlds is on at MIMA until 09 February 2025. Further details available at: www.mima.art/exhibition/towards-new-worlds

images

All installation images are courtesy Middlesbrough Art Week & © Rachel Deakin

Images of Alia Gargum works ©

Colin Davison Photography.

Images of Nightfishing With Ancestors taken from the film courtesy of Karrabing Film Collective.

Images from Towards A New World courtesy of MIMA & © Rachel Deakin. Work shown is Christopher Samuel, The Archive of an Unseen.

Image of The Silence of Ani taken from the film courtesy of Francis Alÿs.

publication date

07 October 2024

tags

Francis Alÿs, The Auxiliary Project Space, Walter Benjamin, Anna Byrne, Kathryn Feeley, Alia Gargum, Kyriaki Goni, High street, Beth Johnson, Karrabing Film Collective, Olana Light, Jonathan McAloon, Middlesbrough, Middlesbrough Art Week, MIMA, Temple Moore, Edel O’Reilly, Pineapple Black, Christopher Samuel, Liam Slevin, Chris Thompson, UPROOT Collective, Christine Walker, Matthew Young

middlesbroughartweek.com

Towards New Worlds is on at MIMA until 09 February 2025. Further details available at: www.mima.art/exhibition/towards-new-worlds