An interview with Ronald Rael about 3d printed mud architecture at Desert X

At this year’s Desert X festival of sculpture held across California’s Coachella Valley, artist & architect Ronald Rael presented Adobe Oasis, a 3d printed mud-construction sculpture not only designed to work aesthetically, but also to test future architectural possibilities using zero-carbon processes. This interview was originally published on our Deeper Recess newsletter in May.

Born in 1971 in Conejos County, Colorado, Ronald Rael studied architecture at Columbia and with the architect Virginia San Fratello, Rael runs Rael San Fratello, a social practice design studio. In 2020, they came to public prominence with Teeter Totter Wall, also winning the London Design Museum’s 2020 Beazley Award. Their widely circulated project saw three pink see-saws that sat through gaps in the Mexico/US border wall allowing residents of El Paso and the Anapra community of Mexico to unite through play.

Rael is also deeply interested in the future of an architecture that benefits communities & the environment, which often incorporates cutting edge technologies. He has overseen pioneering work in 3D printing & has a design & research practice connecting indigenous & traditional materials with modern technologies & social issues.

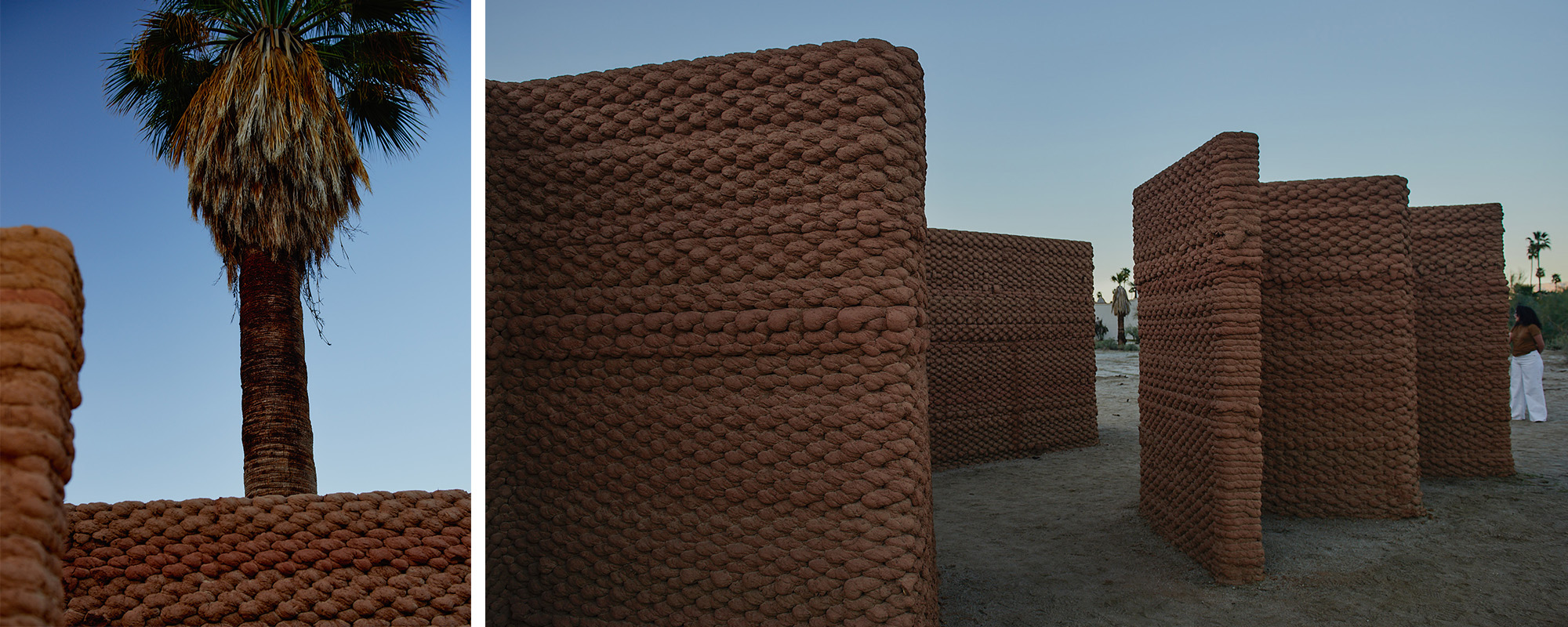

All these points come up in his conversation with recessed.space editor Will Jennings, below, which took place at the centre of Adobe Oasis, Rael’s presentation at this year’s Desert X, the biannual sculpture festival that takes place across California’s Coachella Valley. As excellently shown in exclusive photography by Carlo Zambon, the sculpture is formed of nine distinct geometric walls, zig-zagging & folding to create a series of open & shaded spaces. It is sited at the edge of Palm Springs, home to many landmarks of mid-century domestic architecture, though also a city with many surviving adobe mud houses.

![]()

The work was made by Rael & his team with the help of a 3D printing robot, using an earth mix to fuse cutting edge technology with traditional building processes. Deliberately, it is not a complete architectural object, but more a sculpture with an architectural language & spatial moments. The conversation started by discussing how Adobe Oasis sits somewhere between architecture & art.

This interview was originally published in May on A Deeper Recess, the reader-supported newsletter from recessed.space that runs parallel to the free news update bulleting, The Recess, delivered straight to your inbox.

Please consider subscribing to A Deeper Recess to help support independent writing on art and architecture, more details available HERE.

That was what happened in science as well – since the time of Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo was a scientist but he used painting as a vehicle to communicate scientific ideas, and then became a very good painter and was seen as a painter, seen as an artist, but really, in some ways, was a scientist. I think similarly, this work is really an experiment to think about the movements of the robot, the extensions, the flows of the material, all those things that we must study to make something.

But in the abstract, it's also about the movement of the sun on the texture, and light, and the shadow, and the forms that are taken. So there is something artful and sculptural about it, but it walks that line between not having to have the responsibility that design must have, but also having some responsibility – I've got building permits for this, there are stairs, and it mustn’t fall over.

There was a certain freedom that I was allowed to explore whatever I wanted, and what I wanted to do was to explore ways of making things that might someday become architecture. But it's a proto-architecture, right? It sits in that dirty, messy soup of what's possible – what we might eat and what we might not eat.

![]()

If we polled everyone here, if we gathered all the people here and we asked them, “How many of you have ever lived in an adobe house?” There might be a smattering of hands, probably low numbers, but then, “What about your grandparents?” A few more hands would raise. “How about your great grandparents?” A large percentage would. And if we go back in time, a majority of the people on the planet, no matter where you're from, would have lived in earth homes.

I want to find a way to reintroduce that into the conversation. For me, that's what this project is about, it’s about reintroducing into the conversation questions about how to build what we might need to, about how we're going to build in the future, and to reintroduce earth architecture as a topic into the conversation about how we might build today.

What's interesting about contemporary architecture is that if you cut a section of the wall, there are so many companies trying to find their real estate inside, perhaps twenty companies all with legal counsel finding a home in that wall so they can have their bit of space in a capitalist society. If we cut a section through an adobe house, there are one or two materials maximum! So, it doesn't function well in a capitalist society, but it functions well in a healthy society.

So we have to convince the public, and the public has to make demands.

![]()

In this case, the robot parks up in the centre of the space, and it has an incredible reach. I have made curves before, but I wanted to test a different language. The curve is very stable in mud building and I was very concerned that if we started to make 90-degree angles we might develop very large cracks. What would happen? Would there be separation? Part of this is me wanting to explore what happens with the shrinkage of drying of the material, and at the same time to make the largest reach possible. So, the robot is reaching as far as it can out there, and the walls are as close they can be to the robot, literally just millimetres away. There's a high test of tolerances here, from the maximum to the minimum reach, and testing these sharp angles to explore the behaviour the material. Like I said earlier, it's a scientific experiment.

![]()

It also allows me to test a domestic idea. Part of the reason I chose this site is because I like the fact that from one angle it could look like a remote environment, but from another it could be very connected to the city, and I wanted the steps to allow the visitor to both have an observation of the mountain, an observation of the site of the structure, and also to look beyond the site into Palm Springs as well. And in opposition to this, inside there's a room that really encapsulates you, and it's very tight, and it only frames the sky and the tree.

![]()

![]()

But earth and adobe construction has remained unchanged for 10,000 years, and it's part of a cultural heritage practice for people around the world. It ties us together. So, it's not an alternative, it is the de facto way that we've been doing this for 10,000 years.

Rael is also deeply interested in the future of an architecture that benefits communities & the environment, which often incorporates cutting edge technologies. He has overseen pioneering work in 3D printing & has a design & research practice connecting indigenous & traditional materials with modern technologies & social issues.

All these points come up in his conversation with recessed.space editor Will Jennings, below, which took place at the centre of Adobe Oasis, Rael’s presentation at this year’s Desert X, the biannual sculpture festival that takes place across California’s Coachella Valley. As excellently shown in exclusive photography by Carlo Zambon, the sculpture is formed of nine distinct geometric walls, zig-zagging & folding to create a series of open & shaded spaces. It is sited at the edge of Palm Springs, home to many landmarks of mid-century domestic architecture, though also a city with many surviving adobe mud houses.

The work was made by Rael & his team with the help of a 3D printing robot, using an earth mix to fuse cutting edge technology with traditional building processes. Deliberately, it is not a complete architectural object, but more a sculpture with an architectural language & spatial moments. The conversation started by discussing how Adobe Oasis sits somewhere between architecture & art.

This interview was originally published in May on A Deeper Recess, the reader-supported newsletter from recessed.space that runs parallel to the free news update bulleting, The Recess, delivered straight to your inbox.

Please consider subscribing to A Deeper Recess to help support independent writing on art and architecture, more details available HERE.

recessed.space sits between art and architecture, because sometimes that gap in the middle is frustrating – talking to architects about architecture and to art people about art, it’s often the same conversation, but in different languages. So maybe that's a good place to start, because some people might say, “What's this doing at Desert X? It's architecture, not art!” What do you see as the space between?

That's interesting. I think the space between is a space of responsibility and the space of uselessness. I think art doesn't have the responsibility to be useful, and this work doesn't have the responsibility to be useful either – but it has the potential to be useful, and I'm interested in the possibility of it becoming useful and being employed as a solution for – or rethinking of – how we might make architecture in the 21st century. I've always found it interesting how I entered into the art world through the making of objects that are experiments, and that those experiments, if made beautifully, are seen as art.That was what happened in science as well – since the time of Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo was a scientist but he used painting as a vehicle to communicate scientific ideas, and then became a very good painter and was seen as a painter, seen as an artist, but really, in some ways, was a scientist. I think similarly, this work is really an experiment to think about the movements of the robot, the extensions, the flows of the material, all those things that we must study to make something.

But in the abstract, it's also about the movement of the sun on the texture, and light, and the shadow, and the forms that are taken. So there is something artful and sculptural about it, but it walks that line between not having to have the responsibility that design must have, but also having some responsibility – I've got building permits for this, there are stairs, and it mustn’t fall over.

But it does have a use and a function, as many of the works in Desert X this year do – that is to trigger, to invite questions, or to provoke. Especially in California, after the fires, to ask “How do we rebuild?” So there is a usefulness, an intellectual usefulness maybe, rather than a physical one?

There is an enlightenment or you know, an illumination of certain ideas. Art does that. I don't know if design necessarily illuminates ideas – clients don't hire designers to make a political statement!Sometimes designers might squeeze them in though…

They might smuggle them in somehow, yes. But I think in some ways it's also closer to activism, because designers do many of the things that activists do, except an activist is willing to get arrested for their beliefs. Designers don’t. But a designer has to work with contingencies, make change, work with groups, and come to some consensus around things. Artists don't have to come to consensus around ideas. I think this project is situated in that it doesn't either, necessarily.There was a certain freedom that I was allowed to explore whatever I wanted, and what I wanted to do was to explore ways of making things that might someday become architecture. But it's a proto-architecture, right? It sits in that dirty, messy soup of what's possible – what we might eat and what we might not eat.

But it is an architecture, and the fact that it’s using mud and the adobe process, here in the Coachella Valley, it isn’t just a future architecture, it also looks back. So, there's this dichotomy of the future, which can't just be the Elon Musk-led scientific revolution – which would be terrifying – but also one which is responsible to its history and aware of values.

Yeah, just a couple days ago someone walked over, a neighbour of the site, and she immediately said, “Is this adobe? I live in an adobe house just two blocks away.” She invited me to see the house, an amazing house, it was built in 1935. It's so comfortable, it’s beautiful and elegant. So, this work isn’t futuristic, I think, but it's future forward – it really acknowledges both the past and the present, especially the past as a way that we might move into the future.If we polled everyone here, if we gathered all the people here and we asked them, “How many of you have ever lived in an adobe house?” There might be a smattering of hands, probably low numbers, but then, “What about your grandparents?” A few more hands would raise. “How about your great grandparents?” A large percentage would. And if we go back in time, a majority of the people on the planet, no matter where you're from, would have lived in earth homes.

I want to find a way to reintroduce that into the conversation. For me, that's what this project is about, it’s about reintroducing into the conversation questions about how to build what we might need to, about how we're going to build in the future, and to reintroduce earth architecture as a topic into the conversation about how we might build today.

I live in London, in a brick house, which is obviously earth, but earth which has been through a modern process of reforming and then using cement to lock them together. How do you think we could convince either the industry – architects, developers – to use less cement, glass, steel, and such modern processes? To many in the industry, ideas of earth design may not seem radical, but it is to current processes, systems, and politics.

I don't know if we'll ever be able to convince the industry, but we do need to convince the customers. When we experience tragedies like the fired in Los Angeles, the customers of those homes experienced the tragedy of their homes burning, their land being toxified, their water becoming undrinkable, and their oceans polluted. That's what the customer has received from the industries that provided those materials.What's interesting about contemporary architecture is that if you cut a section of the wall, there are so many companies trying to find their real estate inside, perhaps twenty companies all with legal counsel finding a home in that wall so they can have their bit of space in a capitalist society. If we cut a section through an adobe house, there are one or two materials maximum! So, it doesn't function well in a capitalist society, but it functions well in a healthy society.

So we have to convince the public, and the public has to make demands.

Maybe that is where art can come in, because architecture is not always the best at communicating with the general public, of talking to the public.

All of my work to date has been given value by the art world, and I've had opportunities to improve the technology and skills because of the art world. The architecture world, like construction industry media, only wants to know if it would be cheaper and faster than existing processes, it's a race to the bottom for them, and it leaves no room for innovation. Ultimately, they're stuck. They're stuck in the process of doing what they've done and so I appreciate the world of art for giving value to innovation, community, and risk.

If imagining this project from above, its shape is deliberately non-domestic, non-architectural. It doesn't look like an architectural plan but more of an abstract sculpture. How did you derive that form? Is it from the robot limitations or your aesthetic sensibility?

You know, a lot of my previous projects look at what are the largest reaches a robot can make. I worked with a company inventing a robot that was extremely portable and small. Basically it could reach around and if I made a straight line or a square box, it would be quite small – but if I made it reach as far as it could, it created a circle. And so many of my structures are circular.In this case, the robot parks up in the centre of the space, and it has an incredible reach. I have made curves before, but I wanted to test a different language. The curve is very stable in mud building and I was very concerned that if we started to make 90-degree angles we might develop very large cracks. What would happen? Would there be separation? Part of this is me wanting to explore what happens with the shrinkage of drying of the material, and at the same time to make the largest reach possible. So, the robot is reaching as far as it can out there, and the walls are as close they can be to the robot, literally just millimetres away. There's a high test of tolerances here, from the maximum to the minimum reach, and testing these sharp angles to explore the behaviour the material. Like I said earlier, it's a scientific experiment.

Architecture has post-occupancy evaluations to check how a building and programmes of use are working after completion, so you will have the same thing here? You'll be watching the walls over the next 90 days, revisiting and examining it?

Absolutely. It's already rained twice, so I've seen the behaviour of rain on it, and I have seen the behaviour people in it. Who knows what will happen in the next 90 days? I don't know how people will engage with it and weather will take its time. There are no foundations here, so if it rains a lot the ground might settle and shift. There's a tremendous amount of moisture in these walls, I'm sure it's still not dry at the centre of them yet but I can start to see the moisture finding its way into the ground, and plants are starting to grow up around the base.

And of course there is a tree at the centre of the installation, it’s a reason for choosing this site, to portray the idea of an oasis, aware of the presence of existing moisture in the ground. It’s also kind of a totemic figure of worship at the heart of the work, it's treated with reverence.

This is a site that's been denuded of a lot of vegetation, and oases are incredible because of all the spaces that are amongst what might be hundreds or thousands of trees. I wanted to emulate all these kinds of nooks and spaces, high spaces, low spaces, tight spaces, little views through. Even these gap views are about construction limitations – the robot can't move from a certain spot to another spot without its arm getting twisted, so we decided to stop it and leave these gaps. This is partly design and partly art, it's exploring and science as well.Then you added steps to add just a moment of verticality. Is that another test? It’s one of the few moments of the domestic in the work, or something that people might attribute to architecture, so are these to show people how this might have architectural potential?

There are a few reasons for the steps. I wanted to test what I might make steps out of, and at a certain point I was going to print them all out of mud, but I just thought it was never going to dry so I had to think of other options. If you look underneath the steps, you can see that the robot has actually printed small buttresses that we have placed the wood on, and then it prints over the top to bed and lock them in.It also allows me to test a domestic idea. Part of the reason I chose this site is because I like the fact that from one angle it could look like a remote environment, but from another it could be very connected to the city, and I wanted the steps to allow the visitor to both have an observation of the mountain, an observation of the site of the structure, and also to look beyond the site into Palm Springs as well. And in opposition to this, inside there's a room that really encapsulates you, and it's very tight, and it only frames the sky and the tree.

So would you call this – and this is a big word not all artists like – a political artwork in any way? Whether with a big P or small p – because previous projects of yours have been overtly political.

Someone in the earth architecture world named Simone Swan and I used to talk very much about how all acts of building with earth are political. They're fundamentally political because it is a resistance to contemporary building practices and capitalism, and also an attempt to imagine a new way of living, moving forward with a reverence and respect for the past. So, I think it is a political work. I'd like to think it is political, for sure.And maybe especially so in the current political situation in the United States. You said earlier that artists are maybe allowed to do things that activists don't, but your previous projects, such as Teeter Totter Wall with the see saws through the Mexico-US wall, might not be allowed now and may see you arrested. A very simple gesture, but a big act.

I don't know. I was wondering about testing it again. I may revisit it as a memorial to that idea. I don't know – I'm not into the idea of ambulance chasing art, like all sudden you react and make art based on the headlines. When the Los Angeles fires were happening, I never said, “Hey, I'm solving the LA Fire problem with this.” I never put that forward, but I think there's a very important, sophisticated way that one has to bring the ideas of art into the political conversation. What's the right time to do that? But I think I'm ready to have those conversations with the right people.

Well, just today at SCI-Arc in LA, there was a conference about how the city might rebuild after the fires which – sadly, especially on International Women's Day – was a panel of four men. They did, however, talk a little bit about alternative materials and processes. So maybe some of this is creeping into developers’ conversations, even if the city is not going to be rebuilt in adobe yet.

It’s coming in, yes. But one thing I'd like to make a point about is that this is not an alternative building material. Many times I have conversations with people, they see this and hear the term adobe and they “Oh, do you know about straw bales? Do you know about earthships and tyres, cans, and bottles and super adobe?” I do not believe they should be part of the same conversation because all those alternative building materials are part of a history of waste products from industrial production, whether you're packing bales, making sandbags, grating tyres or cans, they are post-consumer products, and those containers will change. We're not always going to be using rubber tyres, we’re not always going to pack straw in square bales, we're not always going to put rice in those kind of sacks.But earth and adobe construction has remained unchanged for 10,000 years, and it's part of a cultural heritage practice for people around the world. It ties us together. So, it's not an alternative, it is the de facto way that we've been doing this for 10,000 years.

It can be the same in art as well. It's the first material that we would have made art objects with. It’s a material every school child uses to make forms with. It's very familiar to the hand as well. And this project also has a very haptic quality, and every visitor – artist, non-artist, architect, non-architect – will touch it and understand that quality.

I think it's familiar to our genetics. I think we've evolved to squish mud between our hands, to pack it in, to make baskets that hold water, to make effigies, to contain our food and keep it cool, to create shelters that keep us warm and protected. We've evolved to do it, and so we have, in my opinion, a genetic connection to this material, and we don't have a genetic connection to other materials – cans, steel, concrete, and so this is part of that post-occupancy evaluation.But we do have that connection to mud, so I guess that's where art and architecture is a place where that has detached. Architecture has become this super industry in Britain we have had the Grenfell disaster that was a result of processes, materials, the detachment of listening to people, and to the blind trust in modern materials. So maybe this artistic gesture can feed into that conversation.

I believe there's movement of artists around the world who are starting to use adobe, starting to use earth, in political, cultural, and expressive ways. it just seems like there's this moment where the art world is embracing earth and architecture practices as a medium, and that's pretty exciting.Ronald Rael is a designer, activist, trained architect, author, and Eva Li Memorial Chair in Architecture at the University of California Berkeley. He is the Chair of the Department of Art Practice, where he holds a joint appointment and was previously served as Chair of the Department of Architecture, Director of the Masters of Architecture program, and the Director of the Masters of Advanced Architectural Design program in the College of Environmental Design. He is both a Bakar and Hellman Fellow, and directs the printFARM Laboratory (print Facility for Architecture, Research and Materials). His research interests connect indigenous and traditional material practices to contemporary technologies and issues and he is a design activist, author, and thought leader within the topics of additive manufacturing, borderwall studies, and earthen architecture. The London Design Museum awarded his creative practice, Rael San Fratello, (with architect Virginia San Fratello), the Beazley Award in 2021 for the design of the year, one of the most prestigious awards in design internationally. In 2014 his practice was named an Emerging Voice by The Architectural League of New York—one of the most coveted awards in North American architecture. In 2016 Rael San Fratello was also awarded the Digital Practice Award of Excellence by the The Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA).

Rael is the author of Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary (University of California Press 2017), an illustrated biography and protest of the wall dividing the U.S. from Mexico featured in a TED talk by Rael, and Earth Architecture (Princeton Architectural Press, 2008), a history of building with earth in the modern era to exemplify new, creative uses of the oldest building material on the planet. Emerging Objects, a company co-founded by Rael, is an independent, creatively driven, 3D Printing MAKE-tank specialising in innovations in 3D printing architecture, building components, environments and products (a short documentary of their work can be seen here). A monograph of the work of Emerging Objects entitled Printing Architecture: Innovative Recipes for 3D Printing was published in 2018 by Princeton Architectural Press. He was the co-founder of the start-up wood technology company, FORUST, where he maintains a position as design and technology consultant.

Rael earned his Master of Architecture degree at Columbia University in the City of New York, where he was the recipient of the William Kinne Memorial Fellowship. Previous academic and professional appointments include positions at the Southern California Institute for Architecture (SCI_arc), Clemson University, the University of Arizona, and the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in Rotterdam.

www.rael-sanfratello.com

Desert X is produced by The Desert Biennial, a not-for-profit charitable organisation founded in California, conceived to produce recurring international contemporary art exhibitions that activate desert locations through site-specific installations by acclaimed international artists. Its guiding purposes and principles include presenting public exhibitions of art that respond meaningfully to the conditions of desert locations, the environment and Indigenous communities; promoting cultural exchange and education programs that foster dialogue and understanding among cultures and communities about shared artistic, historical, and societal issues; and providing an accessible platform for artists from around the world to address ecological, cultural, spiritual, and other existential themes.

The first Desert X took place in 2017 and included 16 artists who created works for locations from Whitewater Preserve to Coachella. The exhibition and each of the artists received grand acclaim. Since then, a total of 5 biennial exhibitions have taken place in the Coachella Valley, welcoming an audience of over 2M. Since 2020, the organization has engaged in exhibitions outside the United States and helped establish the Desert X AlUla exhibition, in the desert of Saudi Arabia bringing together artists from across that region as well as those from Europe and the U.S.

www.desertx.org

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett & is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

The first Desert X took place in 2017 and included 16 artists who created works for locations from Whitewater Preserve to Coachella. The exhibition and each of the artists received grand acclaim. Since then, a total of 5 biennial exhibitions have taken place in the Coachella Valley, welcoming an audience of over 2M. Since 2020, the organization has engaged in exhibitions outside the United States and helped establish the Desert X AlUla exhibition, in the desert of Saudi Arabia bringing together artists from across that region as well as those from Europe and the U.S.

www.desertx.org

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett & is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

more information

Further details about Adobe Oasis can be found on the Desert X 2025 website: www.desertx.org/dx/dx-25-coachella-valley/ronald-rael

More information about Ronald Rael & his experimental design studio Rael San Fratello, formed with architect Virginia San Fratello, can be found on their website: www.rael-sanfratello.com

images

All photographs © Carlo Zambon for recessed.space.

publication date

05 August 2025

tags

3d printing, Adobe, California, Carbon, Coachella Valley, Desert X, Will Jennings, LA, Los Angeles, Mud, Palm Springs, Ronald Rael, Robot, Sci-Arc, Sculpture, Simone Swan, Technology, Tree, Carlo Zambon, Zero carbon

More information about Ronald Rael & his experimental design studio Rael San Fratello, formed with architect Virginia San Fratello, can be found on their website: www.rael-sanfratello.com