The house as self-portrait: John Soane’s words through an

artistic gaze

An 1812 text by John Soane in which the architect imagines

his own home as a fictional imaginary looked back on from the future was the

starting point for an exhibition organised by artist Charlotte Edey and gallery

Ginny on Frederick. Rochelle Roberts visited Frieze No. 9 Cork Street to find

an array of works from artists & architects who use spatial fragments to

create new narratives.

In a manuscript written in the summer of 1812 and titled Crude Hints Towards an History of my House, architect Sir John Soane imagines his house as a ruin. The manuscript, which was never published during his lifetime, takes the form of a fiction about Soane’s house, which would later become the Sir John Soane’s Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London. Just like Soane’s real home, the house in the text is fragmentary and metamorphic, not quite one thing or the other. The fictional narrator, writing from the future, wonders who might have occupied such a house: “Whilst by some this place has been looked on as a Temple, others have supposed it to have been the residence of some Magician, & in support of this opinion they speak of a large statue placed in the centre of one of the Chapels, which they say might have been this very necromancer changed into Marble.”[1]

A recent exhibition at Frieze No. 9 Cork Street, Crude Hints (Towards), brought together artists working across painting and sculpture to explore how architecture and space can act as reciprocals of meaning using Soane’s text as a vehicle through which to do this.[2] Organised by artist Charlotte Edey and gallery Ginny on Frederick, there is a strong emphasis on materiality, the fragmentary and the uncanny.

figs.i,ii

A key concept of the exhibition is the idea of the house as a self-portrait.[3] In Soane’s text, the artefacts and interiors give the narrator clues about who might inhabit such a house. This can also be seen in Christina Kimeze’s paintings Caryatid (I) and Caryatid (II) (both 2025), for example. Each depict close-ups of architectural fragments in yellow hues. The caryatids of the title, which are rooted in the frame of the paintings as focal points, suggest a temple (just as in Soane’s text) even while the spaces they occupy are hazy and mutable, making it difficult to discern exactly the type of building being shown. In Mary Stephenson’s works Two In The Pink Room and Blue Portion (both 2025) we see sparse modernist interiors rendered in clean lines and muted tones, perhaps revealing the home of an architect, a character that also appears in Soane’s text as a resident of the house.

figs.iii,iv

In the drawing House for the Inhabitant who Refuses to Participate (1979), John Hejduk foregrounds his concept of the ‘architecture of pessimism’ by inserting a new imagined house into a square located in Venice. The house is separate from the buildings on either side of it, a physical gap that emphasises its difference and alienation, and also points to the ‘refusal of participation’ by the person who lives there. In the middle of the square is a viewing tower where people can climb a ladder to observe the inhabitant of the house. To the left of the tower, stands a staircase that leads to nowhere, yet if climbed, can be used to observe observing,[4] in other words, the people on the stairs watch the people in the watch tower watching the person in the house. These uncanny elements problematise the distinction between public and private just as Soane’s house blurs these boundaries by being both a home (private) and a museum (public).

Soane’s house-museum brings together an eclectic mix of objects, artefacts and curiosities relating to magic, esotericism and religion. In Crude Hints (Towards) we can see this interest in religion and magic in various works, including Shigeo Otake’s painting The Crossroads of the Six Realms (2024) which depicts three girls standing at the centre of a crossroads with six pathways leading in different directions. These pathways represent the six possible routes to rebirth in Buddhism (heaven, human, animal, fighting demon, hungry ghost and hell), which is determined by how much karma a person accumulates during their lifetime. Alexandru Chira creates abstract paintings, reminiscent of Hilma af Klint’s spiritualist paintings, that are heavy with cosmological symbolism derived from the quasi-magical system that Chira devoted his life to developing.[5]

figs.v-vii

Aldo Rossi’s Geometrica della memoria (Geometry of Memory, 1978) is part of a series of paintings he made based on fragments of architecture which he assembled into one image to create new, imagined cityscapes. Similarly, Gabrielė Adomaitytė collages imagery together to form complex, multilayered scenes that play with space and perspective. In her painting Grey Made Grey (2025) we look up at a building with a window and balcony through a haze of watery blues and blacks that obscure and obstruct our view and gives the sense of observing through a reflection in a puddle. Longer looking reveals that we appear to be seeing the window through both the interior and exterior of a car, the differing perspectives superimposed on each other. Both Rossi and Adomaitytė’s works speak to the fragmentary nature of Soane’s house, but also, interestingly, through their reimagining of scenes and structures that are rooted in reality, they are also drawing links between Soane’s fictionalisation of his home and the real one that he was in the process of creating.

Okiki Akinfe’s Only Fools and Horses (2025) is a slippery painting that blurs the lines between figuration and abstraction, completeness and incompleteness. Like Adomaitytė, elements of Akinfe’s painting blur and seep into each other. In places, the linen canvas has been left blank or else with thin washes of paint. This reveals the grid of lines beneath the painting, something that Akinfe uses in a lot of her work, and which she has previously likened to scaffolding on a building.[6] The lively and fast-paced feel of the painting is emphasised further with how the canvas curves out from the wall toward the viewer to create the feeling that the two horses in the painting are coming out of the canvas towards the viewer.

figs.viii-x

An interesting interplay between materials runs throughout the exhibition. While some works explore the materiality of the home as physical structure using things like timbre and glass, others employ materials that might be found within the home, such as textiles and cardboard. Matthew Peers’ untitled (2025) is an abstract form reminiscent of a scrap piece of discarded cardboard. Made from dust, gesso salvaged hardboard, timber and shadows, this piece is akin to an imperfect and incomplete structure that bears all the signed of the hand-made. This, we might think of, in relation to Soane’s ‘house as ruin’, a part of a whole that cannot, then, be complete.

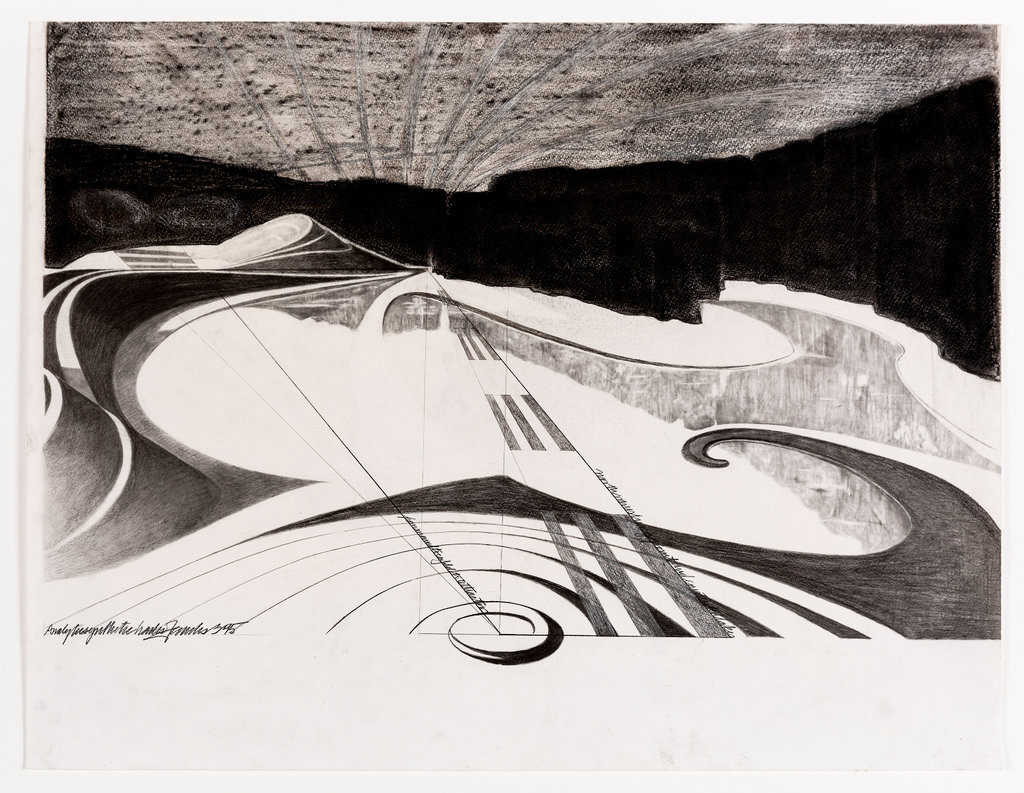

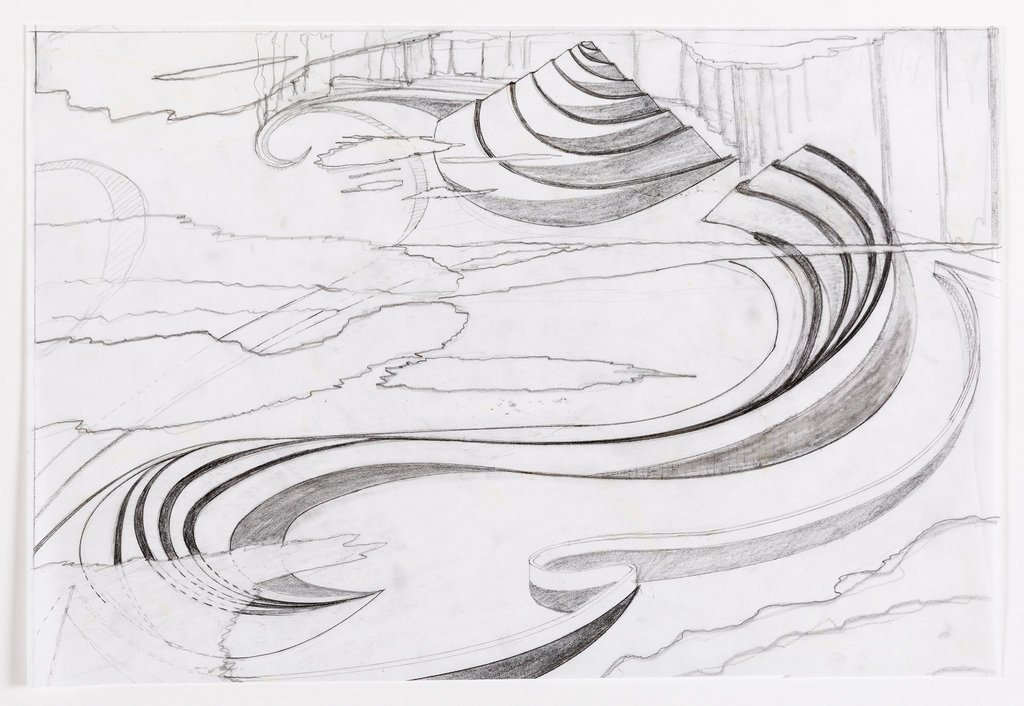

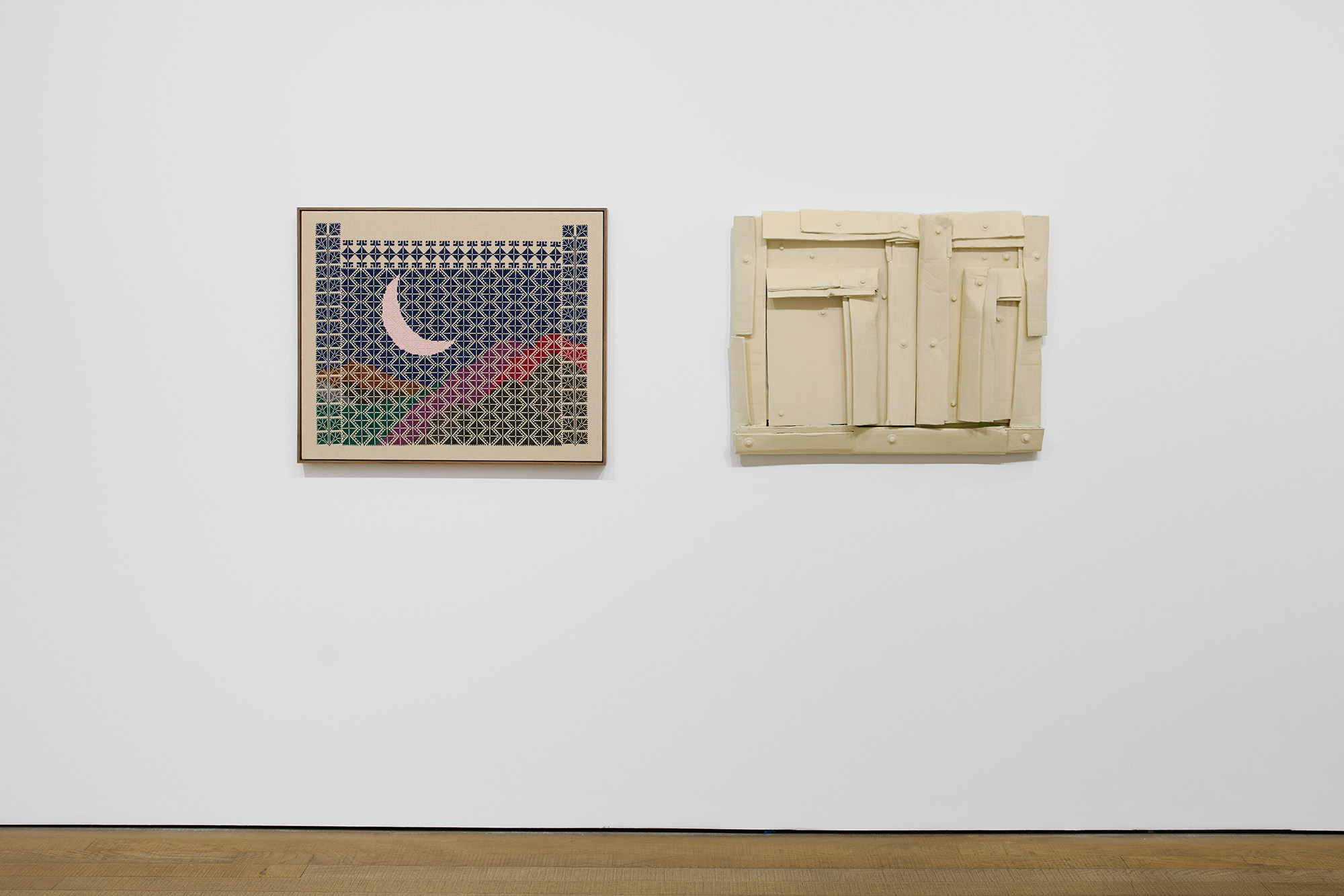

Charlotte Edey’s Axis Drift (2025) uses stained glass and soft pastel on paper to create a window that acts like portal into another realm. We peer through a glittering glass to see a fragmented view behind – large, draped fabrics like curving waves with what could be the horizon behind. The piece is made up entirely of curving and diagonal lines which gives the work tension, a feeling of being off balanced (in fact, many of the works in the show rely on the interplay between curved and straight lines, such as in Charles Jencks’ two plans for the Garden of Cosmic Speculation (c. 1992–3 and 1995) with the spiral mound in opposition to the straight lines of cosmic orientations). Jordan Nassar’s work To Those Who Keep Waiting (2025), on the other hand, adapts the tradition of Palestinian tatreez (cross stitch) which is associated with cushions and other domestic items to create a landscape of colourful mountains, a large moon hanging in the sky.

figs.xi-xiii

Machteld Rullens’ two works Crème Barn and Crushed Agnes on a Trip (both 2025) are made from found cardboard and epoxy resin. By flattening the boxes and painting them, fixing them in place (again, like Soane’s necromancer into marble) Rullens brings them out of their original context as functional objects into the sphere of painting (and you can see the influence of, for instance, the painter Agnes Martin in Crushed Agnes on a Trip). Julien Monnerie does a similar thing with his sculpture Asparagus (2025) made from silver-plated pewter. In this piece, Monnerie playfully reinterprets the medium of pewter – often used for making tableware such as cutlery – to create a holder for an asparagus, the very thing you might use a pewter item to eat it with.

Crude Hints (Towards) is a multifaceted and excitingly curated show. While many of the works link to concepts and ideas explored in Soane’s text Crude Hints Towards an History of my House, they also expand upon these ideas, revealing the interplay between identity and the home, and how these structures and viewpoints can be unfixed, can fluctuate and transform.