On entering Jonathan Martin’s (?) Imperial Palace

In trying to determine who drew a fantastical palace Will Jennings went on a journey of curiosity in which absences are louder than truth, and into the world of Jonathan Martin.

“What a subject for John Martin!”, a lady in the

crowd exclaimed as flames flickered through York Minster in 1829. Perhaps in

her mind she was comparing the fire in front of her with artist John

Martin’s painting, the apocalyptic The Fall of Nineveh, exhibited in the same year and

reproduced widely as a mezzotint print.

Unbeknown to her, a few hours earlier the fire had been started by Jonathan Martin, the biblical-historicist artist’s younger brother. If the Martins’ parents had known the lives their children would lead, they might have considered naming John and Jonathan less awkwardly for future essayists, but their father being a lowly journeyman tanner would have little expected their extraordinary legacies.

![]()

![]()

In any case, Jonathan was brought up for the main not by his parents but his aunt, a staunch Protestant whose vivid tales of hellfire and damnation must have drawn forceful images firmly into his young imagination. Despite having eleven siblings he dwelled in a solitude, prone to midnight solitary excursions to Hexham’s mines, perhaps internalising rather than vocalising his thoughts due to ankyloglossia - a shortened skin between his tongue and mouth. Of all his family, he was closest to his sister, until he witnessed her murder at the hands of a neighbour, the first of countless traumatic experiences feeding his imagination and mental health, which he later rendered in words, art, and arson.

It’s an impossible task to translate such a peculiar and eventful life as Jonathan’s into a short essay, and there’s little point in trying. All I can do is draw a faint impression, to sketch key elements which perhaps may help you form your own interpretation. A drawing might be made of lines intended to communicate a clarity of idea, but mark-making is a process which at its core is one of enclosing absences, and in reading or translating that drawing, or a sketch of any medium – ink, words, action - it is those very absences which offer the most fertility.

![]()

fig.iii

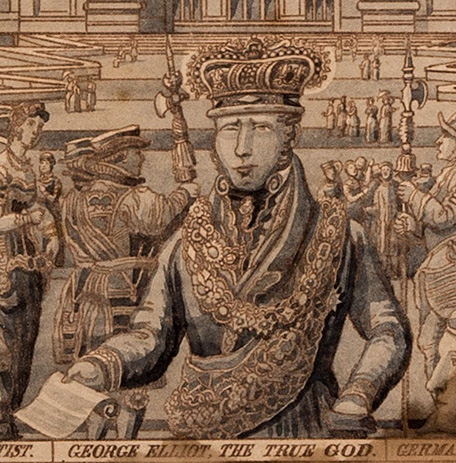

This ink drawing of the Imperial Palace, attributed to a George Elliot, has no end of absences. There is a lot of volume and stuff within it to consider, perhaps too much, and maybe it’s even somehow deliberately obtuse and confused. Evidently the Palace is not a real place - not that any rendering of a place is - but what kind of place is it? Most of the Drawing Matter archive within which it’s held is indexed, understood, and anchored to something of substance - a built project, theoretical development, or individual’s creative arc - but this drawing isn’t. It’s untethered. Yes, it can be found and located within the physical space and catalogue (item number 2606), but its history, meaning, purpose and idea is loose.

Who is the George Elliot it is ascribed to? What is the fantastical Imperial Palace which it depicts? And what of the staccato capital texts along the bottom? EMPEROR OF THE WORLD. THE TRUE AND LAWFUL GOD. There is so much drawn here that seems nonsensical contradiction. Where to begin translating this drawing into words or meaning?

![]()

![]()

![]()

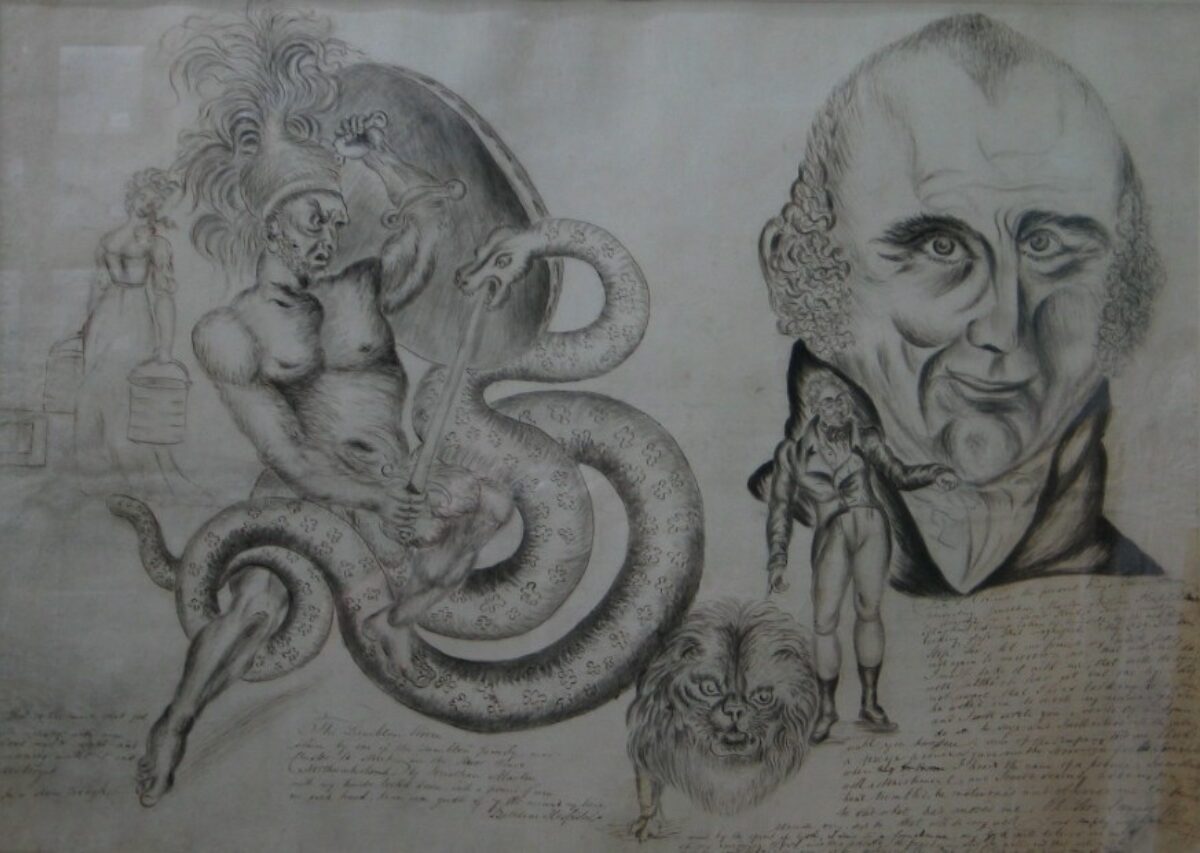

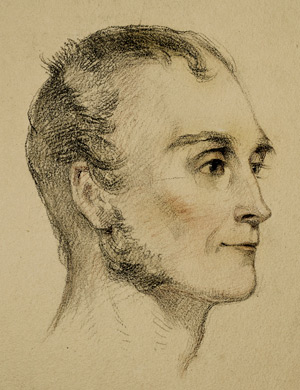

Dr. Henry Noltie told me of his “throwaway suggestion” that the portrait of GEORGE ELLIOT, THE TRUE GOD looked somewhat similar to Jonathan Martin, the arsonist. It’s true, Martin’s self-portrait within his drawing The Lambton Worm and Self Portrait in the Bethlem Museum of the Mind renders a similar pursed smile, knobbly nose, cleft chin, and generous sideburns. But Jonathan died in 1838, 18 years before the 1856 indicated in the bottom line of text:

The likeness may be coincidental, but when relying on absences coincidence is a start. A key source into any excavation of Jonathan’s story is his autobiography, Of The Life of Jonathan Martin, of Darlington, Tanner, published three times between 1825 and 1828, which he personally hawked across Northern England for a few pence a copy, riding a donkey and dressed in coat and boats made of seal skin, hairy side out. He is, perhaps predictably, an unreliable narrator of his own story – potential truths becoming entangled with romanticisation, prophetic visions, and political foretelling of future states.

Aged 22 Jonathan moved to London to find work on Indian continent trading ships, though while visiting the Monument to the Great Fire of London he was pressganged. Six (mis)adventurous years in the Navy followed, then more sailing work on trade and merchant military ships, criss-crossing from Cadiz to Cairo, capturing Spaniards, and warring Danes. His dramatic tales pile up: He prevented an explosion by extinguishing burning pistol wadding smouldering besides 500 barrels of gunpowder after the gunner’s yeoman shot his brains across the ship’s store; he was knocked out and rescued from drowning more than once; he severely damaged his skull in a fall, and in another from a ship’s rigging scalped a fellow sailor by grabbing his ponytail to break his descent; he once deserted the Navy, got drunk, lost his trousers, then walked in a long confused circle before accidentally returning to his ship, and apologetically climbing back on board.

It was while in blockades of Cadiz in the last years of the 18th century, frequently seeing his life flash before his eyes as shore batteries attacked his ship. He decided to return to England to become a Wesleyan Methodist and embark on a proselytising mission. Years later at his trial for arson, a Chelsea Pensioner who had been one of his ship companians, said: “He was a very good sailor, but had fits of melancholy … would talk of dying and a future state.” In the third edition of Martin’s biography, after acknowledging the popularity of his older brother John’s artwork, he self-described as having “…the gift of prophecy, which is the best of all, for I feel that God is with me.”

![]()

Between his 1829 trial and death in 1838, Jonathan resided at the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, or Bedlam, in a white-washed room with a table, chair, and single grated window so high up it only offered a view into the sky. An 1833 a magazine reported him as being “perfectly satisfied” in the room, wanting nothing other than his supply of “Indian ink and Brookman’s black-lead pencils”. His older brother’s art career was booming. John’s engravings and paintings of biblical spectacle were touring and sold across a burgeoning cultural marketplace. Jonathan was giving away his drawings and writings to visiting strangers.

Drawing was a key component of communication to Jonathan, arguably moreso than it was for his brother for whom it was a career but not a singular mode of communication. While John rendered the stories of others into drama and awe as prophetic warnings, Jonathan was using his drawing to translate and explain stories never told by anyone else, ones he believed were told directly to him alone. Straight from his mind onto paper, sincerely rendering messages he felt received from God, concealed within his ever-vivid dreams.

Throughout his life, Jonathan’s dreams repeatedly summoned the character of the “Son of Napoleon”, an imagined future conqueror of England who starred in a recurring dream in which French armies marched from the sea along the Northeast of England, initiated war, then headed south to burn London. Jonathan believed he would one day meet the younger Emperor, and felt he would work alongside him to ensure the nation worshipped the Lord in the correct Wesleyian way.

![]()

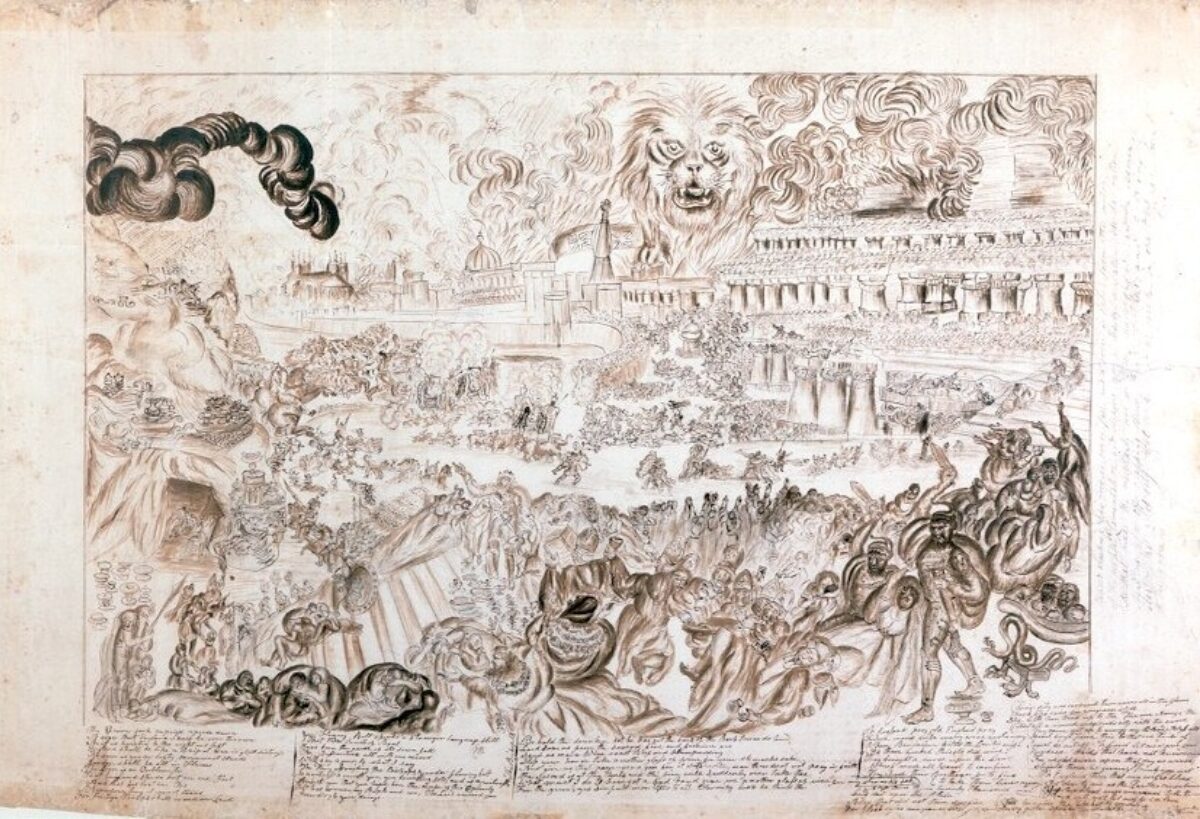

One of his drawings, rendered around 1830 from his Bethlam cell, was The Fall of London. Carrying a remarkable likeness to his brother’s fall of Nineveh – rows of columns seemingly transformed into industrial architecture – it shows not only that drawing was a key method of him transferring his future hopes and visions, but a present awareness of his celebrated brother’s work, adopting his aesthetic to propel his own ideas.

So, what of the fantastical Imperial Palace itself? I suspect it’s a drawing by Jonathan Martin, as Noltie half-wondered. The marks carry his signature, and it is rendered in Indian ink as supplied by Bedlam staff. I see within the imagined palace’s solomonic columns, openwork spires, turreted towers, and pyramid crowns a potential assemblage of the Egyptian, Sicilian, and other architectures he might have encountered over his sailing years.

Perhaps, with a squint, it’s possible to see in the Imperial Palace elements of the distant Gibeon city as imagined in his brother’s breakthrough 1816 painting Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gibeon - sketches of which he took to show Jonathan shortly before the younger brother was first committed to a lunatic asylum (after threatening to shoot the Bishop of Oxford - a whole other story... That first asylum was in Norton, but he was soon moved to one in Sherrif Hill, Gateshead – about a mile from the Bensham Asylum written into the Imperial Palace footer.

Perhaps George Elliot is Jonathan’s pseudonym. Beyond the facial likeness, maybe he imagined his post-asylum self central to a new world order. Or perhaps Elliot was an imagined future hero imaginary, based on Admiral George Elliot, born in 1813, who served alongside Martin at the Siege of Cadiz - the very moment he changed his life trajectory.

![]()

![]()

All drawings are two dimensional. Whether a scrawled attempt to rationalise a momentary passing thought, or a considered geometric drafting of realistic representation. They are flat, only showing one idea of an idea, and perhaps ultimately never possible to be translated from author to viewer with the intended meaning carrying across accurately. When committing a vision to paper - whether architect, artist, or writer - is there not an element of prophecy, of committing to some imaginary hoping others read and follow your vision? And in trying to take in that same image, is the reader not also employing a kind of prophetic gaze, locating within the sketch various real and imagined trajectories, past and future, personal and shared, trying to extract from the rendering an idea of truth contained within the absences?

All sketches - whether with Indian ink or black-lead pencils, images or words - are perhaps doomed to never truly represent or be accurately read. As a process of translation from internal imagination to external representation, and then ingested from that representation to another’s imagination, what is lost, what was never there, what is assumed, and what is overlayed?

Maybe the Imperial Palace drawing does not represent any truth other than an amalgamation of Jonathan Martin’s memories, dreams, and visions. Maybe in the search to determine who the artist was, it is discovered that neither Elliot or Martin truly existed, but both, just as the Palace, are a melting of histories, imaginaries, and futures.

Is it possible to write about a drawing composed of absences and unreliability? Where does the reader’s eye end and imagination begin, and can I be sure in that attempting to find a semblance of sense within such a deliberately obtuse drawing as the Imperial Palace I am not in fact drawing my own new prophecies, histories, and false-truths, compelled by a desire to understand, compounded and made real through this essay?

Unbeknown to her, a few hours earlier the fire had been started by Jonathan Martin, the biblical-historicist artist’s younger brother. If the Martins’ parents had known the lives their children would lead, they might have considered naming John and Jonathan less awkwardly for future essayists, but their father being a lowly journeyman tanner would have little expected their extraordinary legacies.

figs.i-ii

In any case, Jonathan was brought up for the main not by his parents but his aunt, a staunch Protestant whose vivid tales of hellfire and damnation must have drawn forceful images firmly into his young imagination. Despite having eleven siblings he dwelled in a solitude, prone to midnight solitary excursions to Hexham’s mines, perhaps internalising rather than vocalising his thoughts due to ankyloglossia - a shortened skin between his tongue and mouth. Of all his family, he was closest to his sister, until he witnessed her murder at the hands of a neighbour, the first of countless traumatic experiences feeding his imagination and mental health, which he later rendered in words, art, and arson.

It’s an impossible task to translate such a peculiar and eventful life as Jonathan’s into a short essay, and there’s little point in trying. All I can do is draw a faint impression, to sketch key elements which perhaps may help you form your own interpretation. A drawing might be made of lines intended to communicate a clarity of idea, but mark-making is a process which at its core is one of enclosing absences, and in reading or translating that drawing, or a sketch of any medium – ink, words, action - it is those very absences which offer the most fertility.

fig.iii

This ink drawing of the Imperial Palace, attributed to a George Elliot, has no end of absences. There is a lot of volume and stuff within it to consider, perhaps too much, and maybe it’s even somehow deliberately obtuse and confused. Evidently the Palace is not a real place - not that any rendering of a place is - but what kind of place is it? Most of the Drawing Matter archive within which it’s held is indexed, understood, and anchored to something of substance - a built project, theoretical development, or individual’s creative arc - but this drawing isn’t. It’s untethered. Yes, it can be found and located within the physical space and catalogue (item number 2606), but its history, meaning, purpose and idea is loose.

Who is the George Elliot it is ascribed to? What is the fantastical Imperial Palace which it depicts? And what of the staccato capital texts along the bottom? EMPEROR OF THE WORLD. THE TRUE AND LAWFUL GOD. There is so much drawn here that seems nonsensical contradiction. Where to begin translating this drawing into words or meaning?

figs.iv-vi

Dr. Henry Noltie told me of his “throwaway suggestion” that the portrait of GEORGE ELLIOT, THE TRUE GOD looked somewhat similar to Jonathan Martin, the arsonist. It’s true, Martin’s self-portrait within his drawing The Lambton Worm and Self Portrait in the Bethlem Museum of the Mind renders a similar pursed smile, knobbly nose, cleft chin, and generous sideburns. But Jonathan died in 1838, 18 years before the 1856 indicated in the bottom line of text:

GEORGE ELLIOT, EMPEROR OF THE

WORLD, DREW THIS PICTURE, IT IS THE ESPECIAL PROPERTY, AND FOR THE ESPECIAL

MORAL USE OF GEORGE ELLIOT EMPEROR OF THE WORLD. BENSHAM ASYLUM, NEAR

GATESHEAD, COUNTY OF DURHAM. 1856.

The likeness may be coincidental, but when relying on absences coincidence is a start. A key source into any excavation of Jonathan’s story is his autobiography, Of The Life of Jonathan Martin, of Darlington, Tanner, published three times between 1825 and 1828, which he personally hawked across Northern England for a few pence a copy, riding a donkey and dressed in coat and boats made of seal skin, hairy side out. He is, perhaps predictably, an unreliable narrator of his own story – potential truths becoming entangled with romanticisation, prophetic visions, and political foretelling of future states.

Aged 22 Jonathan moved to London to find work on Indian continent trading ships, though while visiting the Monument to the Great Fire of London he was pressganged. Six (mis)adventurous years in the Navy followed, then more sailing work on trade and merchant military ships, criss-crossing from Cadiz to Cairo, capturing Spaniards, and warring Danes. His dramatic tales pile up: He prevented an explosion by extinguishing burning pistol wadding smouldering besides 500 barrels of gunpowder after the gunner’s yeoman shot his brains across the ship’s store; he was knocked out and rescued from drowning more than once; he severely damaged his skull in a fall, and in another from a ship’s rigging scalped a fellow sailor by grabbing his ponytail to break his descent; he once deserted the Navy, got drunk, lost his trousers, then walked in a long confused circle before accidentally returning to his ship, and apologetically climbing back on board.

It was while in blockades of Cadiz in the last years of the 18th century, frequently seeing his life flash before his eyes as shore batteries attacked his ship. He decided to return to England to become a Wesleyan Methodist and embark on a proselytising mission. Years later at his trial for arson, a Chelsea Pensioner who had been one of his ship companians, said: “He was a very good sailor, but had fits of melancholy … would talk of dying and a future state.” In the third edition of Martin’s biography, after acknowledging the popularity of his older brother John’s artwork, he self-described as having “…the gift of prophecy, which is the best of all, for I feel that God is with me.”

fig.vii

Between his 1829 trial and death in 1838, Jonathan resided at the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, or Bedlam, in a white-washed room with a table, chair, and single grated window so high up it only offered a view into the sky. An 1833 a magazine reported him as being “perfectly satisfied” in the room, wanting nothing other than his supply of “Indian ink and Brookman’s black-lead pencils”. His older brother’s art career was booming. John’s engravings and paintings of biblical spectacle were touring and sold across a burgeoning cultural marketplace. Jonathan was giving away his drawings and writings to visiting strangers.

Drawing was a key component of communication to Jonathan, arguably moreso than it was for his brother for whom it was a career but not a singular mode of communication. While John rendered the stories of others into drama and awe as prophetic warnings, Jonathan was using his drawing to translate and explain stories never told by anyone else, ones he believed were told directly to him alone. Straight from his mind onto paper, sincerely rendering messages he felt received from God, concealed within his ever-vivid dreams.

Throughout his life, Jonathan’s dreams repeatedly summoned the character of the “Son of Napoleon”, an imagined future conqueror of England who starred in a recurring dream in which French armies marched from the sea along the Northeast of England, initiated war, then headed south to burn London. Jonathan believed he would one day meet the younger Emperor, and felt he would work alongside him to ensure the nation worshipped the Lord in the correct Wesleyian way.

fig.viii

One of his drawings, rendered around 1830 from his Bethlam cell, was The Fall of London. Carrying a remarkable likeness to his brother’s fall of Nineveh – rows of columns seemingly transformed into industrial architecture – it shows not only that drawing was a key method of him transferring his future hopes and visions, but a present awareness of his celebrated brother’s work, adopting his aesthetic to propel his own ideas.

So, what of the fantastical Imperial Palace itself? I suspect it’s a drawing by Jonathan Martin, as Noltie half-wondered. The marks carry his signature, and it is rendered in Indian ink as supplied by Bedlam staff. I see within the imagined palace’s solomonic columns, openwork spires, turreted towers, and pyramid crowns a potential assemblage of the Egyptian, Sicilian, and other architectures he might have encountered over his sailing years.

Perhaps, with a squint, it’s possible to see in the Imperial Palace elements of the distant Gibeon city as imagined in his brother’s breakthrough 1816 painting Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gibeon - sketches of which he took to show Jonathan shortly before the younger brother was first committed to a lunatic asylum (after threatening to shoot the Bishop of Oxford - a whole other story... That first asylum was in Norton, but he was soon moved to one in Sherrif Hill, Gateshead – about a mile from the Bensham Asylum written into the Imperial Palace footer.

Perhaps George Elliot is Jonathan’s pseudonym. Beyond the facial likeness, maybe he imagined his post-asylum self central to a new world order. Or perhaps Elliot was an imagined future hero imaginary, based on Admiral George Elliot, born in 1813, who served alongside Martin at the Siege of Cadiz - the very moment he changed his life trajectory.

fig.ix, x

All drawings are two dimensional. Whether a scrawled attempt to rationalise a momentary passing thought, or a considered geometric drafting of realistic representation. They are flat, only showing one idea of an idea, and perhaps ultimately never possible to be translated from author to viewer with the intended meaning carrying across accurately. When committing a vision to paper - whether architect, artist, or writer - is there not an element of prophecy, of committing to some imaginary hoping others read and follow your vision? And in trying to take in that same image, is the reader not also employing a kind of prophetic gaze, locating within the sketch various real and imagined trajectories, past and future, personal and shared, trying to extract from the rendering an idea of truth contained within the absences?

All sketches - whether with Indian ink or black-lead pencils, images or words - are perhaps doomed to never truly represent or be accurately read. As a process of translation from internal imagination to external representation, and then ingested from that representation to another’s imagination, what is lost, what was never there, what is assumed, and what is overlayed?

Maybe the Imperial Palace drawing does not represent any truth other than an amalgamation of Jonathan Martin’s memories, dreams, and visions. Maybe in the search to determine who the artist was, it is discovered that neither Elliot or Martin truly existed, but both, just as the Palace, are a melting of histories, imaginaries, and futures.

Is it possible to write about a drawing composed of absences and unreliability? Where does the reader’s eye end and imagination begin, and can I be sure in that attempting to find a semblance of sense within such a deliberately obtuse drawing as the Imperial Palace I am not in fact drawing my own new prophecies, histories, and false-truths, compelled by a desire to understand, compounded and made real through this essay?