Venice Biennale: an interview with Anish Kapoor

Anish Kapoor’s deep connection to Venice & the city’s Biennale has deepened now he has purchased a run-down palazzo to transform into gallery, studio &café. It won’t open fully until 2024, but he is showing work within it’s construction site aesthetic, allowing a fresh connection between his practice & architecture. Will Jennings spoke to the artist about that connection & how architectural issues impact his work.

Anish Kapoor is a regular feature at

Venice Biennale. Since representing Britain in 1990, he is regularly exhibited

within the official or collateral exhibitions across a city dear to his heart. For

an artist working around concepts of spatial unreliability, depth and depthlessness,

and shifting perceptions, there are perhaps many shared characteristics between

his creations and the city around them.

That relationship is only going to grow further. Kapoor has bought a Palazzo, and is working with architect Giulia Foscari of UNA studio and local firm FWR Associati to renovate it into a studio, gallery, and public café. It’s a glorious space, purchased by tobacco merchant Count Gorolamo Manfrin in 1788 who used the first floor as a picture gallery visited by many, including John Ruskin, Edouard Manet, Lord Byron, and Antonio Canova. It had been empty for many years before the Anish Kapoor Foundation acquired it, and with its history of art it’s not only suited to its future use as a making and showing space, but it will also more deeply root Kapoor within the city he loves, and ensure he will have exhibitions for many Biennale to come.

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.i-iii

I met Kapoor in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, a former church and monastery partially renovated by Andrea Palladio in the 1560s. Kapoor has a solo exhibition on in the gallery, running parallel to an installation he is showing in the building site of Palazzo Manfrin the other side of the city.

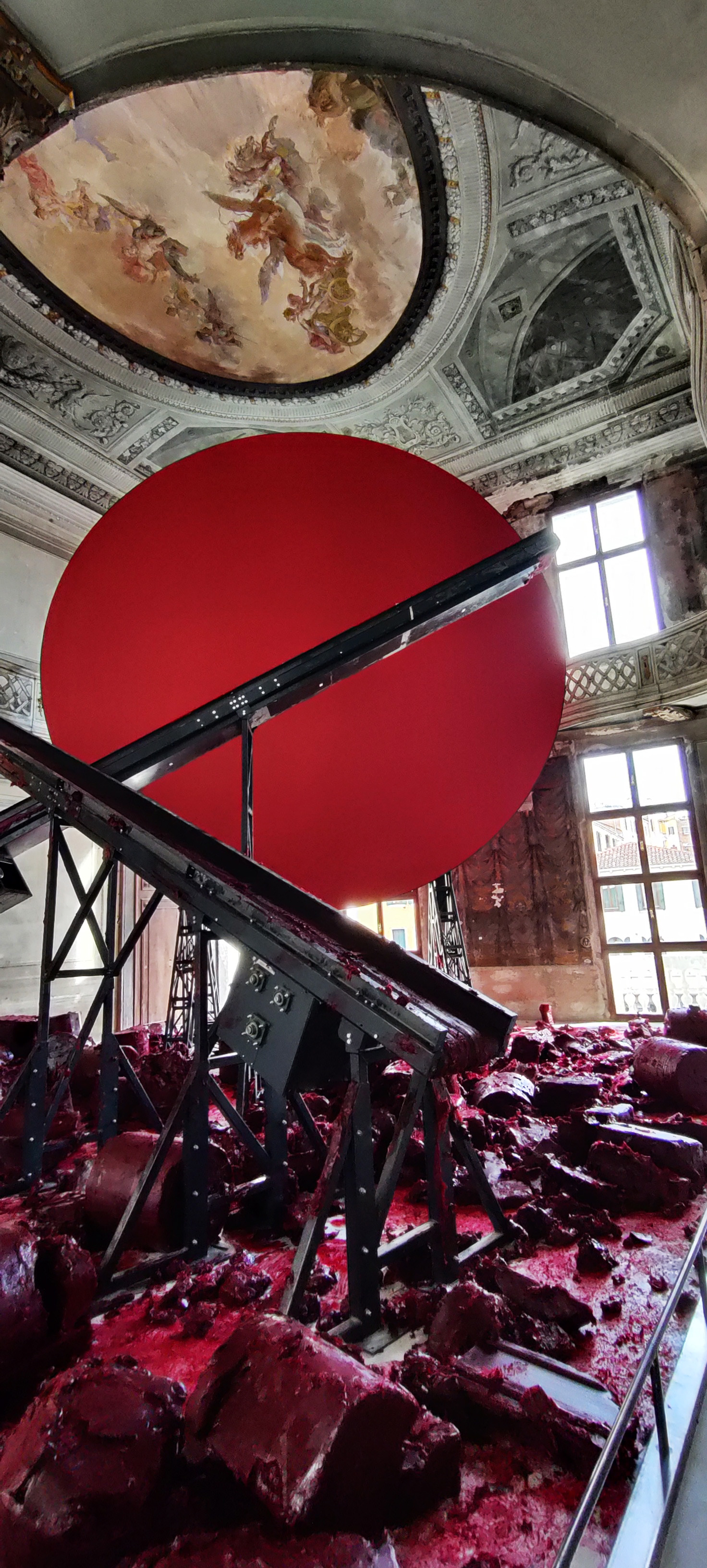

The Accademia exhibition is neat and a white wall hang, while his Palazzo Manfrin installation is playful and riffs off the de/construction of the place. As a building site, it has portaloos not built-in toilets, the strata of his alabaster works riff off the cracked plaster of the walls, and his trademark red wax pieces which in this location seem to bleed through the building – it looks like he had fun exploring the architecture in relation to his practice. I begin by asking him about Palazzo Manfrin:

It has always been the intention to under-restore that building to go to a high finish, but to do the opposite and leave it with all this history. You know, it was it was the home of a great collector, Mr. Manfrin, and then a nunnery, and then a school, and all sorts. So, to leave those layers of history and add to it – add to it! So, yes you're right, it’s a bleeding building.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.iv-viii

Kapoor’s works are crammed into Accademia spaces, except for one crisp white room which is empty save for a single cut into the wall – as if Lucio Fontana had taken a knife to it – delicately rupturing the space. It’s The Healing of St Thomas (1989), perhaps alluding to the doubts of Apostle Thomas after he touched the resurrected Jesus’ wounds. It’s also a piece Kapoor mentions when thinking about architecture in relation to his work:

There’s that work, The Healing of St. Thomas, alone in a room, and I keep returning to the idea of a building and architecture as a proto-self. It's not just a thing, it's a body, and the idea that somehow, we make things again, and again, and again, in the image of ourselves, however we fashion them – I do feel that's terribly, terribly important.

Sadly, much contemporary architecture has taken huge distance from this idea and has turned, if I may be so bold, into another capitalist project, another project for the occupation of money. So those things that distance culture and the arts from the deeply human are to be lamented, in my view. It’s very hard in the contemporary world to hold that space, but that's a whole subject in itself.

![]()

Kapoor’s work is profoundly spatial. In Palazzo Manfrin he plays with the historic function of space – the blood-red vortex of Turning Water into Mirror, Blood into Sky (2003) sits in the centre of the courtyard where a well-head would sit; he responds to immediate aesthetics – a room of his concave mirror works speak to a circular ceiling painting above; and he saturates the very structure – the vast machinery of Symphony for a Beloved Son (2013), which transports and drops great lumps of deep red wax, appears to leak through the floor of its grand first floor to form vast ceiling-hung sculpture Mount Moriah at the Gate of the Ghetto (2022) in the vestibule directly below.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.x-xiv

More broadly, his work relates to varying scales of space – whether the industrial Middlesbrough landscape or a more formal urban set-piece such as Chicago’s Millennium Park. I ask Kapoor about this idea of the scale of work and the human mentioned:

Sculpture is fundamentally about that. It doesn't really matter who you look at, all great sculptors have worked in this relation - even the great land artists. Interestingly, it didn't happen until man went into space and could we could see for the first time the globe as an object, and then all these things occur. So it runs at all sorts of levels it seems to me.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.xv-xviii

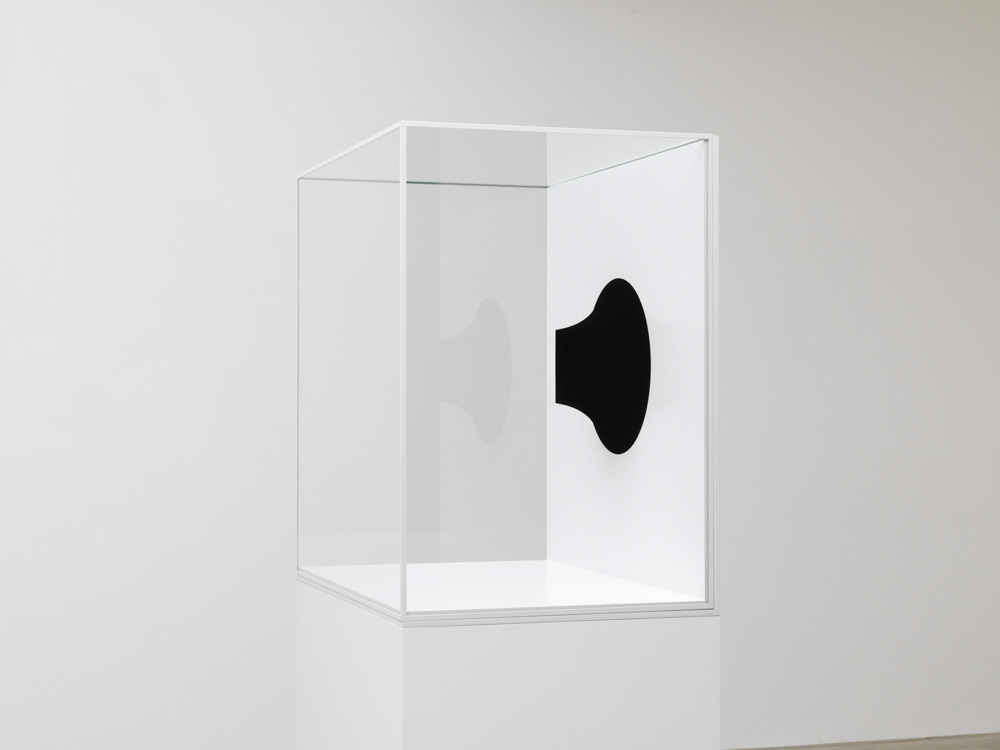

This consideration of distance, and the human removing themselves from the planet to see it in new light, indicates Kapoor is not only talking about a physical relationship to the human, but also psychological. Works made in Vantablack, the most intensely dark pigment known and which absorbs all light which hits, are shown for the first time in his two Venice exhibitions. They are disorientating and compelling. Head on reading as a flat surface image of a shape, and only after moving your body around the space do you see them side-on and realise there’s vast depth, an invisible physicality. They connect the physical and psychological, reminding that one intrinsically depends on the other in the understanding of space. Much of his work is about the distortion of space, whether in a vitrine of a Palazzo, it seeks to deform rigidity and question coordinates.

Exactly, it’s about uncertainty. Here we are standing in front of what I think is a Palladio façade – though it’s been messed around with – and he played with this idea of both orienting the body and also giving it space and direction, scale plays such a vital role in that, and then also disorientating, taking away scale. They are both equally important. And scale isn't a matter of size. As the artist Barnett Newman says, scale is a matter of relationship, and the way that meaning emerges in the size of a thing. It’s rather beautiful that idea, I think.

![]()

![]()

Standing in front of Palladio, and thinking of those Vantablack dimensionless forms, I think of Teatro Olimpico, Palladio’s 1580s Vicenza theatre with trompe-l'œil stage scenery read as perspectival streets from the seats, but up close become nonsensical distortions of reality. Kapoor’s installation at Palazzo Manfrin plays with these deep conceptual ideas, and more, weaving the physical and psychological within the fabric of a building in (dis)repair – exploring a new form or relationship for the artist, not just that of the human but also to a specific new building, one which will be explore for many years to come.

![]()

fig.xxi

That relationship is only going to grow further. Kapoor has bought a Palazzo, and is working with architect Giulia Foscari of UNA studio and local firm FWR Associati to renovate it into a studio, gallery, and public café. It’s a glorious space, purchased by tobacco merchant Count Gorolamo Manfrin in 1788 who used the first floor as a picture gallery visited by many, including John Ruskin, Edouard Manet, Lord Byron, and Antonio Canova. It had been empty for many years before the Anish Kapoor Foundation acquired it, and with its history of art it’s not only suited to its future use as a making and showing space, but it will also more deeply root Kapoor within the city he loves, and ensure he will have exhibitions for many Biennale to come.

figs.i-iii

I met Kapoor in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, a former church and monastery partially renovated by Andrea Palladio in the 1560s. Kapoor has a solo exhibition on in the gallery, running parallel to an installation he is showing in the building site of Palazzo Manfrin the other side of the city.

The Accademia exhibition is neat and a white wall hang, while his Palazzo Manfrin installation is playful and riffs off the de/construction of the place. As a building site, it has portaloos not built-in toilets, the strata of his alabaster works riff off the cracked plaster of the walls, and his trademark red wax pieces which in this location seem to bleed through the building – it looks like he had fun exploring the architecture in relation to his practice. I begin by asking him about Palazzo Manfrin:

It has always been the intention to under-restore that building to go to a high finish, but to do the opposite and leave it with all this history. You know, it was it was the home of a great collector, Mr. Manfrin, and then a nunnery, and then a school, and all sorts. So, to leave those layers of history and add to it – add to it! So, yes you're right, it’s a bleeding building.

figs.iv-viii

Kapoor’s works are crammed into Accademia spaces, except for one crisp white room which is empty save for a single cut into the wall – as if Lucio Fontana had taken a knife to it – delicately rupturing the space. It’s The Healing of St Thomas (1989), perhaps alluding to the doubts of Apostle Thomas after he touched the resurrected Jesus’ wounds. It’s also a piece Kapoor mentions when thinking about architecture in relation to his work:

There’s that work, The Healing of St. Thomas, alone in a room, and I keep returning to the idea of a building and architecture as a proto-self. It's not just a thing, it's a body, and the idea that somehow, we make things again, and again, and again, in the image of ourselves, however we fashion them – I do feel that's terribly, terribly important.

Sadly, much contemporary architecture has taken huge distance from this idea and has turned, if I may be so bold, into another capitalist project, another project for the occupation of money. So those things that distance culture and the arts from the deeply human are to be lamented, in my view. It’s very hard in the contemporary world to hold that space, but that's a whole subject in itself.

fig.ix

Kapoor’s work is profoundly spatial. In Palazzo Manfrin he plays with the historic function of space – the blood-red vortex of Turning Water into Mirror, Blood into Sky (2003) sits in the centre of the courtyard where a well-head would sit; he responds to immediate aesthetics – a room of his concave mirror works speak to a circular ceiling painting above; and he saturates the very structure – the vast machinery of Symphony for a Beloved Son (2013), which transports and drops great lumps of deep red wax, appears to leak through the floor of its grand first floor to form vast ceiling-hung sculpture Mount Moriah at the Gate of the Ghetto (2022) in the vestibule directly below.

figs.x-xiv

More broadly, his work relates to varying scales of space – whether the industrial Middlesbrough landscape or a more formal urban set-piece such as Chicago’s Millennium Park. I ask Kapoor about this idea of the scale of work and the human mentioned:

Sculpture is fundamentally about that. It doesn't really matter who you look at, all great sculptors have worked in this relation - even the great land artists. Interestingly, it didn't happen until man went into space and could we could see for the first time the globe as an object, and then all these things occur. So it runs at all sorts of levels it seems to me.

figs.xv-xviii

This consideration of distance, and the human removing themselves from the planet to see it in new light, indicates Kapoor is not only talking about a physical relationship to the human, but also psychological. Works made in Vantablack, the most intensely dark pigment known and which absorbs all light which hits, are shown for the first time in his two Venice exhibitions. They are disorientating and compelling. Head on reading as a flat surface image of a shape, and only after moving your body around the space do you see them side-on and realise there’s vast depth, an invisible physicality. They connect the physical and psychological, reminding that one intrinsically depends on the other in the understanding of space. Much of his work is about the distortion of space, whether in a vitrine of a Palazzo, it seeks to deform rigidity and question coordinates.

Exactly, it’s about uncertainty. Here we are standing in front of what I think is a Palladio façade – though it’s been messed around with – and he played with this idea of both orienting the body and also giving it space and direction, scale plays such a vital role in that, and then also disorientating, taking away scale. They are both equally important. And scale isn't a matter of size. As the artist Barnett Newman says, scale is a matter of relationship, and the way that meaning emerges in the size of a thing. It’s rather beautiful that idea, I think.

figs.xix,xx

Standing in front of Palladio, and thinking of those Vantablack dimensionless forms, I think of Teatro Olimpico, Palladio’s 1580s Vicenza theatre with trompe-l'œil stage scenery read as perspectival streets from the seats, but up close become nonsensical distortions of reality. Kapoor’s installation at Palazzo Manfrin plays with these deep conceptual ideas, and more, weaving the physical and psychological within the fabric of a building in (dis)repair – exploring a new form or relationship for the artist, not just that of the human but also to a specific new building, one which will be explore for many years to come.

fig.xxi

Anish Kapoor was born in Mumbai, India

in 1954 and lives and works in London. He studied at Hornsey College of Art,

London, UK (1973–77) followed by postgraduate studies at Chelsea School of Art,

London, UK (1977–78). Recent solo exhibitions include Modern Art Oxford, UK (2021);

Museum of Contemporary Art and Urban Planning, Shenzhen, China (2021); Houghton

Hall, Norfolk, UK (2020); and Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany (2020), He

represented Britain at the 44th Venice Biennale in 1990 with Void Field (1989),

for which he was awarded the Premio Duemila for Best Young Artist. Kapoor won

the Turner Prize in 1991 and has honorary fellowships from the University of

Wolverhampton, UK (1999), the Royal Institute of British Architecture, London,

UK (2001) and an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford, UK (2014).

Anish Kapoor was awarded a CBE in 2003 and a Knighthood in 2013 for services to

visual arts. Large scale public projects include Cloud Gate (2004) in

Millennium Park, Chicago, USA and Orbit (2012) in the Queen Elizabeth

Olympic Park, London, UK and Ark Nova (2013) the world's first

inflatable concert hall in Japan.

www.anishkapoor.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info

visit

Anish Kapoor’s exhibitions at Galleria dell’Accademia and Palazzo Manfrin, Venice - collaborations between Anish Kapoor Studio and Lisson Gallery

with support from Galleria Continua, Galleria Massimo Minini, Galerie Kamel Mennour, Kukje Gallery, Regen Projects and SCAI The Bathhouse -

run until 9 October 2022. More details available at:

www.gallerieaccademia.it/en/anish-kapoor-0

images

fig.i Installation at Palazzo Manfrin. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © David Levene.

fig.ii The Palazzo Manfrin. Photograph

© Luca Zanon.

fig.iii

Installation at Palazzo Manfrin. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © Attilio Maranzano.

figs.iv-vi

Installation at Palazzo Manfrin. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © Will Jennings.

fig.vii

Installation at Palazzo Manfrin. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph ©

Attilio Maranzano.

fig.viii

Installation at Palazzo Manfrin. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © David Levene.

fig.ix

Installation at Galleria dell’Accademia. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © Will Jennings.

figs.x-xiii

Installation at Palazzo Manfrin. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © Will Jennings.

fig.xiv

Installation at Palazzo Manfrin. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © David Levene.

fig.xv

Installation at Galleria dell’Accademia. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © Will Jennings.

figs.xvi-xviii

Installation at Galleria dell’Accademia. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph ©

David Levene.

fig.xix

Installation at Galleria dell’Accademia. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph ©

Attilio Maranzano.

fig.xx

Installation at Galleria dell’Accademia. © Anish Kapoor, Photograph © David Levene.

fig.xxi Portrait of Anisk Kapoor (2021). © George Darrell.

publication date

18 August 2022

tags

FWR Associati, Black, Galerie Kamel Mennour,

Galleria Continua,

Galleria dell’Accademia,

Galleria Massimo Minini, Anish Kapoor, Kukje Gallery,

Lisson Gallery, Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Manfrin, Barnett Newman, Psychology, Regen Projects, Saint Thomas,

SCAI The Bathhouse, Space, Teatro Olimpico, Vantablack, Venice, Venice Biennale

www.gallerieaccademia.it/en/anish-kapoor-0