A flâneur in uncanny valley: traversing the digital landscape

In the exhibition How to Win at Photography - Image-Making as Play, The Photographers’ Gallery explore the impact of video games and digital realm upon image making and photography. One of the elements covered is landscape. recessed.space carried out some digital archaeology into the pixel-soil to see what can be dug up.

Over the early 1960s, artist Ed Ruscha frequently drove from his Los Angeles home to his parents in Oklahoma. On one of these journeys, he stopped at each and every petrol station, made a photograph, then went on his way. The images formed the content, presented alone with no contextual text, for his book Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), a work which became a iconic modern artistic rendering of landscape. The journey back to his parents as a North American road trip, each photograph acting as an unsubtitled chapter in an unseen protagonist’s journey, the buildings acting as stations of the cross on a Christian pilgrimage.

That all these petrol stations were along Route 66 compounded his project not only within landscape history, but also cultural. The road, by then already mythologised in Easy Rider and Grapes of Wrath - and ever since only more a part of the country’s idea of modern nostalgia of place - dealt with that very American construct of capitalist infrastructure as culture, explored throughout modern arts, and a key component of the translation of popart from its British origins into a recognisably American product, part of its global image.

![]()

fig.i

The petrol station, by nature of its connection to ubiquitous global infrastructure is also a symbol recognised worldwide, and so that it has naturally slipped into video game logistics is perhaps not unexpected – petrol stations are often the go-to place in role-playing games to refuel the avatar or find a new vehicle to take ownership of, you may divert through one on a city racing game to instantly repair your car, or they may be one of the few locations of orientation on a world map to locate your avatar within a digi-landscape.

The Photographers’ Gallery pairs Ruscha’s book with Lorna Ruth Galloway’s series of charcoal screenprint images depicting six of the petrol stations in Los Santos, the rerendered version of Los Angeles which forms the urban and natural landscape of Grand Theft Auto V. It’s perhaps not surprising to find that it is not the only artwork referencing GTA V - the game was hugely influential in not only game design, but wider arts and academia, a hyper-realistic landscape which seemed to trap within its pixels a depth of image and textual thinking about place, city, and reality.

There is an theory by Atkinson & Willis’ academic paper The Mediation of Urban and Simulated Space and Rise of the Flâneur Electronique (2007) of the import, segue, and slip: the first being how real-world aesthetic is adopted into the digital; the segue being when a gamer puts down the controller, enters the physical realm and for a period has a mental overlap between the two, dragging a memory of the digital into reality; while the slip, in the authors’ words, is “a temporary interpretation of an element of real urban contexts in the language, narrative or physical constructs of the game world.”[1]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Other items have been excavated from the Los Santos landscape and reframed. There it is as a backdrop in Roc Herms’ images of a finger being stuck up into the first-person view, referencing a series by Ai Weiwei – shown alongside – in which the artist enacts the gesture against various global cultural and political landmarks.

It recurs on Joan Pamboukes’ landscape images, alongside scenery from Metal Gear, and Kill Zone, as restful and classical landscape photography, the aesthetic belying the inherent unreality and violence of the source material. It’s not stated where Alan Butler’s cyanotypes of cacti are from, but some may well be extracted from Los Santos and transformed into quasi-historical images reflecting both photographic history as well as digital futures.

![]()

As we head deeper into uncanny valley, it’s this space between the virtual and real which is not only of interest to artists, but also engineers, ethicists, and scientists, and while the exhibition How to Win at Photography is primarily interested in the former, it’s no surprise that the works touch beyond the aesthetic & test the space between realms.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.vii-x

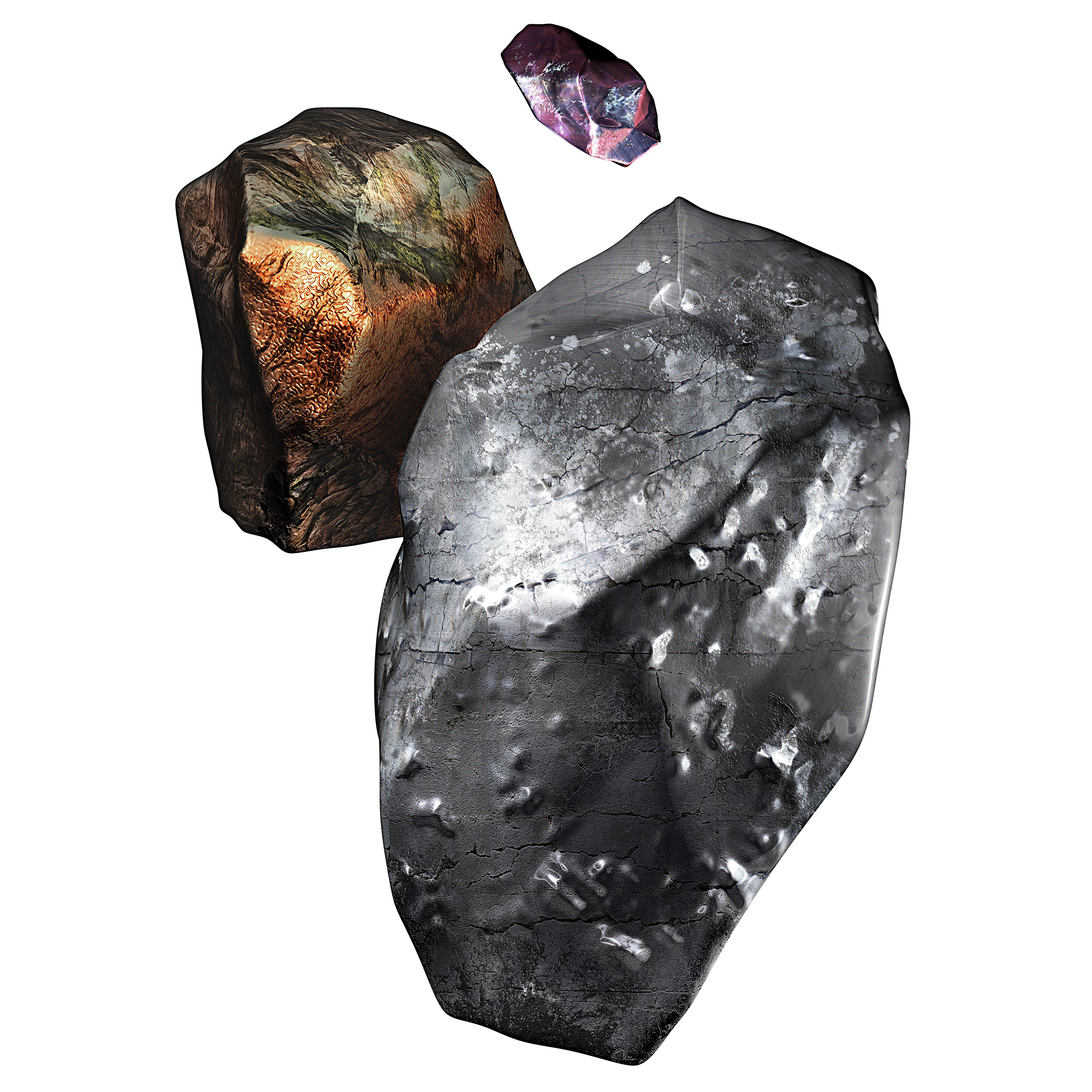

Tabor Robak’s series Rocks (2011) presents 198 isolated 3D rocks, as if plucked from the mountainous terrain of Los Santos and here presented as archaeological evidence. It’s at once absurd, but also not – this is an archaeology, and even in the decade that’s passed since the making of his work technology has progressed at such a level that his rocks seem somewhat antiquated, and so even though digital, these do speak to a different age and a different digital landscape.

A work by Cory Arcangel also calls for concentration of place. He has taken the great American road trip and reimagined it as purgatory, taking a SNES games and stripping out the gameplaying elements to leave only the contextual landscape. By manipulating hard- and software, the artist has removed the vehicles from F1 Racer, which now becomes a never-ending journey along a tarmac road towards mountains which never arrive, and by removing Mario and his journey from Super Mario Bros it becomes a 21st century version of Luke Howard or John Constable’s cloud studies, These are psychological landscapes as much as physical.

![]()

Art has often been a domain into which we can take our anxieties, worldly thoughts, and personal trials into as a foil or muse to look at the work but really look at ourselves, here by removing competition and game, Arcangel introduces the same function as a vehicle of reflection.

Landscapes, however – whether real or virtual – are not apolitical. They are constructs of a culture, are formed by laws, capital, law, and power, and so should be read as containers of the politics embedded within. This is true whether it’s a Capability Brown landscape concealing the violence of uprooted villages, diverted rivers, and forced vistas, as much as it is true of Los Santos landscapes created through overtime crunch and frat boy culture of Rockstar, the developer behind the Grand Theft Auto series.

![]()

fig.xii

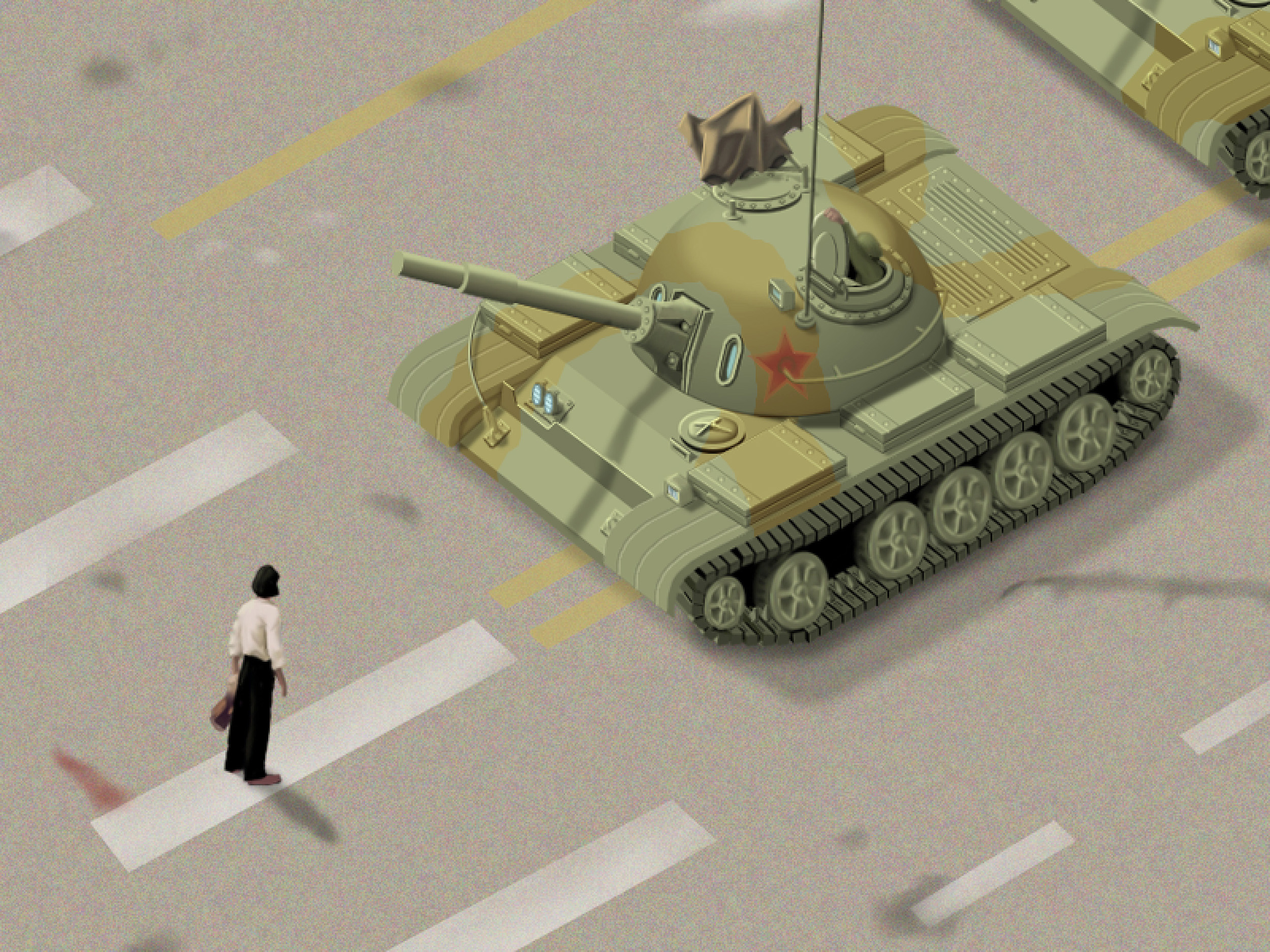

The invisibility of a landscape or view is also political, the concealment of a moment, a formation, or a truth, buried aesthetically or physically. So it is with a selection of images in the exhibition depicting the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, specifically the famed image of Tank Man standing with shopping bags in front of a line of military vehicles which later would enact carnage upon peaceful student protestors. Around the world, gamers recreate the celebrated image and share through online forums and platforms, often into China where the image – and discussion of it – is silenced.

Photographs of the event will not show up on Chinese search engines, this digital version of a critical landscape moment might get through, and with it carry pointers of discussion and help a the story lock into a new generation’s cultural memory where the powers that be sought to remove all residue. Even in the digital, the buried can be dug up, and through the digital new renderings of the physical may emerge.

![]()

fig.xiii

[1] Atkinson, R. and Willis, P. (2007). Charting the ludodrome: The mediation of urban and simulated space and rise of the flâneur electronique. Information, Communication & Society, 10(6), pp.818–845.

That all these petrol stations were along Route 66 compounded his project not only within landscape history, but also cultural. The road, by then already mythologised in Easy Rider and Grapes of Wrath - and ever since only more a part of the country’s idea of modern nostalgia of place - dealt with that very American construct of capitalist infrastructure as culture, explored throughout modern arts, and a key component of the translation of popart from its British origins into a recognisably American product, part of its global image.

fig.i

The petrol station, by nature of its connection to ubiquitous global infrastructure is also a symbol recognised worldwide, and so that it has naturally slipped into video game logistics is perhaps not unexpected – petrol stations are often the go-to place in role-playing games to refuel the avatar or find a new vehicle to take ownership of, you may divert through one on a city racing game to instantly repair your car, or they may be one of the few locations of orientation on a world map to locate your avatar within a digi-landscape.

The Photographers’ Gallery pairs Ruscha’s book with Lorna Ruth Galloway’s series of charcoal screenprint images depicting six of the petrol stations in Los Santos, the rerendered version of Los Angeles which forms the urban and natural landscape of Grand Theft Auto V. It’s perhaps not surprising to find that it is not the only artwork referencing GTA V - the game was hugely influential in not only game design, but wider arts and academia, a hyper-realistic landscape which seemed to trap within its pixels a depth of image and textual thinking about place, city, and reality.

There is an theory by Atkinson & Willis’ academic paper The Mediation of Urban and Simulated Space and Rise of the Flâneur Electronique (2007) of the import, segue, and slip: the first being how real-world aesthetic is adopted into the digital; the segue being when a gamer puts down the controller, enters the physical realm and for a period has a mental overlap between the two, dragging a memory of the digital into reality; while the slip, in the authors’ words, is “a temporary interpretation of an element of real urban contexts in the language, narrative or physical constructs of the game world.”[1]

figs.ii-v

Other items have been excavated from the Los Santos landscape and reframed. There it is as a backdrop in Roc Herms’ images of a finger being stuck up into the first-person view, referencing a series by Ai Weiwei – shown alongside – in which the artist enacts the gesture against various global cultural and political landmarks.

It recurs on Joan Pamboukes’ landscape images, alongside scenery from Metal Gear, and Kill Zone, as restful and classical landscape photography, the aesthetic belying the inherent unreality and violence of the source material. It’s not stated where Alan Butler’s cyanotypes of cacti are from, but some may well be extracted from Los Santos and transformed into quasi-historical images reflecting both photographic history as well as digital futures.

fig.vi

As we head deeper into uncanny valley, it’s this space between the virtual and real which is not only of interest to artists, but also engineers, ethicists, and scientists, and while the exhibition How to Win at Photography is primarily interested in the former, it’s no surprise that the works touch beyond the aesthetic & test the space between realms.

figs.vii-x

Tabor Robak’s series Rocks (2011) presents 198 isolated 3D rocks, as if plucked from the mountainous terrain of Los Santos and here presented as archaeological evidence. It’s at once absurd, but also not – this is an archaeology, and even in the decade that’s passed since the making of his work technology has progressed at such a level that his rocks seem somewhat antiquated, and so even though digital, these do speak to a different age and a different digital landscape.

A work by Cory Arcangel also calls for concentration of place. He has taken the great American road trip and reimagined it as purgatory, taking a SNES games and stripping out the gameplaying elements to leave only the contextual landscape. By manipulating hard- and software, the artist has removed the vehicles from F1 Racer, which now becomes a never-ending journey along a tarmac road towards mountains which never arrive, and by removing Mario and his journey from Super Mario Bros it becomes a 21st century version of Luke Howard or John Constable’s cloud studies, These are psychological landscapes as much as physical.

fig.xi

Art has often been a domain into which we can take our anxieties, worldly thoughts, and personal trials into as a foil or muse to look at the work but really look at ourselves, here by removing competition and game, Arcangel introduces the same function as a vehicle of reflection.

Landscapes, however – whether real or virtual – are not apolitical. They are constructs of a culture, are formed by laws, capital, law, and power, and so should be read as containers of the politics embedded within. This is true whether it’s a Capability Brown landscape concealing the violence of uprooted villages, diverted rivers, and forced vistas, as much as it is true of Los Santos landscapes created through overtime crunch and frat boy culture of Rockstar, the developer behind the Grand Theft Auto series.

fig.xii

The invisibility of a landscape or view is also political, the concealment of a moment, a formation, or a truth, buried aesthetically or physically. So it is with a selection of images in the exhibition depicting the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, specifically the famed image of Tank Man standing with shopping bags in front of a line of military vehicles which later would enact carnage upon peaceful student protestors. Around the world, gamers recreate the celebrated image and share through online forums and platforms, often into China where the image – and discussion of it – is silenced.

Photographs of the event will not show up on Chinese search engines, this digital version of a critical landscape moment might get through, and with it carry pointers of discussion and help a the story lock into a new generation’s cultural memory where the powers that be sought to remove all residue. Even in the digital, the buried can be dug up, and through the digital new renderings of the physical may emerge.

fig.xiii

[1] Atkinson, R. and Willis, P. (2007). Charting the ludodrome: The mediation of urban and simulated space and rise of the flâneur electronique. Information, Communication & Society, 10(6), pp.818–845.

The Photographers’ Gallery opened in 1971 in Covent Garden, London, as the UK’s first independent and publicly funded gallery devoted to photography. It was the first UK gallery to exhibit many key names in international photography, including Juergen Teller, Robert Capa, Sebastiano Salgado and Andreas Gursky. The Gallery has also been instrumental in establishing contemporary British photographers, including Martin Parr and Corinne Day. In 2009 the Gallery relocated to a new multi-storey building in Ramillies Street, Soho and opened its doors to the public in 2012 after an ambitious redevelopment plan which provided the Gallery with three floors of state-of-the-art exhibition space as well as an education/events studio, a gallery for commercial sales, bookshop and cafe. The success of The Photographers’ Gallery over the past five decades has helped to secure the medium’s position as a vital and highly regarded art form, introducing new audiences to photography and championing its place at the heart of visual culture.

www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk

visit

How to Win at Photography - Image-Making as Play is on at The Photographers’ Gallery until 25 September 2022.

www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/how-to-win-at-photography

images

fig.i

How to Win at Photography installation image. Photograph © Kate Elliot.

fig.ii Ai Weiwei, Study of Perspective - The White House, Washington D.C. USA, (1995).

Ai Weiwei Studio. Courtesy the artist, Lisson Gallery and neugerriemschneider, Berlin.

fig.iii-v Roc Herms, from the series Study of Perspective (2015). Courtesy the artist © Roc Herms.

fig.vi

How to Win at Photography installation image. Photograph © Kate Elliot.

fig.vii Justin Berry, Monte Puncu (2018), from the series Road Trips (2018).

© Justin Berry.

fig.viii

Justin Berry, Mojo Coyo (2018), from the series Road Trips (2018).© Justin Berry.

figs.ix,x Tabor Robak, detail views from Rocks (2011). © Tabor Robak.

figs.xi,xii

How to Win at Photography installation images. Photograph © Kate Elliot.

fig.xiii Jon Haddock, Wang Weilin (2000) from the series The Screenshots (2000). © Jon Haddock

publication date

22 August 2022

tags

Cory Arcangel, Archaeology, Rowland Atkinson, Capability Brown, Alan Butler, Computer games, Digital, Games, Lorna Ruth Galloway, Grand Theft Auto V, GTA V, Roc Herms, Landscape, Los Santos, Mario, Joan Pamboukes, Play, SNES, Tabor Robak, Rockstar, Route 66, Ed Ruscha, Tank man,

The Photographers Gallery,

Tiananmen Square, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Uncanny valley, Video games, Ai Weiwei, Paul Willis

www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/how-to-win-at-photography