Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: worldbuilding a cyberpunk playground

Mixed-media & video game artist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley has created an immersive world which straddles analogue & digital, gallery & youth club, Liverpool & cyberpunk imaginary. She has concoted a world of escape & self reflection, a site to forge identity & imagine what an urban future of empathy may be. Will Jennings spoke to the artist about her process & the world that has been created.

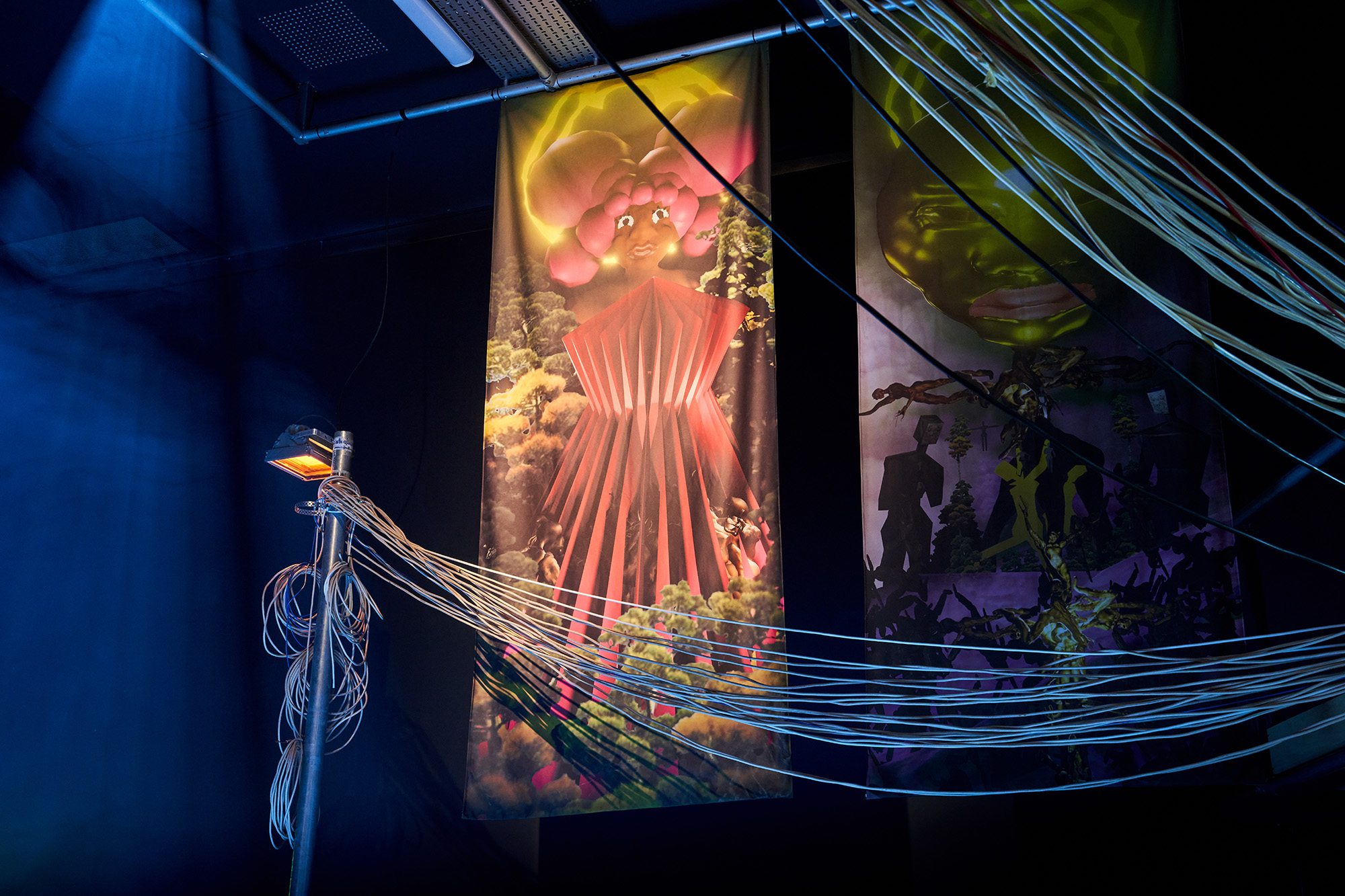

The journey starts at a bus stop – street furniture which offers both place of congregation and departure – from where a visitor crosses the threshold into a space of unknown darkness. Next to the roadworks, a tin shack has detritus piling up

outside it, with scaffolding running up its façade. Flyposted leaflets shouting

FEEL FREE BECOME MEAT are fixed to the steel framework, and a peak inside the

shack reveals piles more of the leaflets swept into a corner amongst empty crisp

packets. Back outside, conjoined and chaotic cabling wends its way from the hut’s

scaffolding up to a series of lampposts across the landscape, bathing a disconcertingly

yellow, plasticated floor in a gloomth. Municipal swings hang flaccid, and

nearby a gauze-covered construction glows with semi-invitation from the

cyberpunk scene, a sofa, TV, and lamp act as a domestic pull away from the

anxiety outside. Characters look down disconcertingly from the darkness, not

announcing yet if they are friend or foe.

![]()

![]()

This totalising situation is the creation of Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, who has designed the immersive urban space for her exhibition at FACT in Liverpool. While initially, the place may feel oppressive and uneasy, the longer a visitor dwells the more it becomes apparent that this is not a place to be feared so much as occupied and experienced, speaking to ideas that an ideal world does not need to be designed top-down, but might emerge from communities and peoples who inhabit and create it from within - however chaotic and cluttered it may read to those outside.

Brathwaite-Shirley’s exhibition, When Our Worlds Meet, grew out of conversations with such a community. Working with a collective of diverse and energised young people from the city, self-titled as The Bandidos, the artist asked simple worldbuilding questions: How would you redesign Liverpool for your community? What does your world need? What rules does your world have?

![]()

As an artist exploring fictional futures – of dystopian and utopian bent – Brathwaite-Shirley utilises video games within her practice, with a joyful punk approach to process and aesthetic. Self-declaring as creating “work that seeks to archive black trans experience,” her art is deliberately confrontational and frequently puts the visitor – or participatory gamer in a gallery context – into moments of awkwardness, self awareness, and shedding light onto privilege and status.

All the works in this show require engagement, physically with controllers to choose paths through text and images, but also mentally. Computer games differ from static, passively viewed artworks through their need to be activated and how the user becomes embodied within the avatar or agent represented on screen or responding to decisions. “With a game, you’re responsible for what you see and you’re responsible for what you don’t see – the amount of energy you put in is what you’ll get back from the work,” the artist shares, though then adds that the freedom of choice of possibility inherent within games is not always true, the artist playing with that notion of openness and control: “My main medium is the audience, because I want to move how they are thinking, looking, and feeling in the space – rather than them thinking they have control over the entire environment in the game because I often take control away, or give them just enough.”

![]()

This is not only true of gaming worlds though. The real worlds we inhabit – whether urban back-alley as presented in this gallery, or more polished environments from shopping centres to landscaped parks, also shape our agency, politics, and embodied sense of self. Architectures are built by and for certain bodies – usually white, male, heteronormative bodies – and through digital and gaming, Brathwaite-Shirley helps force an imagining of being in someone else’s world with less control, hoping to not only conjure a re-consideration of both self and place, but also help forge empathy.

The Bandidos and their reading of urban spaces are present throughout the installation. Over the course of a year, the artist ran workshops with the group under the creative auspices of forming a temporary video game company. “We would have conversations, drawing sessions, workshops, modelling sessions, so we could get a general gist so I could understand them and what they’re trying to say in the narrative,” the artist explains. The group then storyboarded ideas which Brathwaite-Shirley developed into the games which are spread across the exhibition, inviting interaction not only with the digital stories but also the constructed space itself.

![]()

Sitting on the swings a visitor looks up at a screen showing their experience of a rollercoaster. Text appears: THIS RIDE WAS NOT MADE FOR YOU, THIS RIDE WILL NOT LISTEN TO YOU, YOU FEEL LIKE YOU HAVE GIVEN UP CONTROL, BUT NOW YOU WANT IT BACK. In classic choose-your-own-adventure style, different paths can be taken, but whichever is chosen a reckoning with anything from self, politics, culture, and place will be needed to progress – while travelling cyber-gothic tracks through a world of polygon shapes and mapped textures, The Rollercoaster of Your Past asks questions about the self you once were, of your pride or embarrassment of yourself, and how that shaped who you are now or may become.

THERE ARE OVER 40,000 CHILDREN MINING FOR YOUR LEISURE, bold text shouts from the building site puddle. Then: ON YOUR WAY HOME YOU PASS A GROUP OF PEOPLE, AS YOU WALK BY ONE OF THEM BREAKS AWAY FROM THE GROUP AND BEGINS FOLLOWING YOU. These stories are forged from listening to the group over the workshops, then reimagining and fragmenting these range of thoughts into the artist’s individual recognisable aesthetic. But underneath the aesthetic there are a whole range of urban teenage concerns and observations from a disparate group of varied identities and personal stories.

“I feel like my job is to make sure all these disparate conversations come together in one space, because without that, it would be a mess – which I would kind of enjoy, but as I'm trying to build a new world that might exist for them, a mess is not what they need,” the artist explains. She adds that, “I usually describe myself as a mediation person during the process and then towards the end I’m a director, when I put it all together. Most of the process was just listening and not creating anything, just listening and listening and listening.”

![]()

Cities often design out the youth. Whether it’s hostile architecture to prevent congregation, a lack of spaces for teenagers to simply be without having to be consumers, or more aggressive tactics such Public Space Protection Orders or even sonic devices which emit alarms so high-pitched only dogs and younger ears can hear, designed to create youth-free spaces. Added to that, over the last decade youth clubs and spaces have closed down across the country due to underfunding. “When I was younger, I used to go to a youth club, but my youth club closed down as well,” Brathwaite-Shirley explains, sarcastically adding, “because our government is great.”

The exhibition exists as a kind of youth club, in lieu of those destroyed by Conservative decisions. Free to visit, the artist wants the city’s youth to take ownership, explaining that “the aim was to create a little city space that will be used by them.” Before the show opened to the art-loving, grown-up public, the kids were let in first to improve and personalise the space. The artist goes on, “every weekend, more kids from Liverpool will do that, so by the end of the show it should all look different - I want them to be able to graffiti and create something that will start fuck up the space, taking over. The rule I'm setting is that any young person who wants to come in and practice space is allowed to, I want the space to be theirs and for them to stamp their claim on it.”

![]()

Despite decades of outreach, a changing landscape of art appreciation, and ongoing work around what art is and who it’s for, galleries are still predomenantly populated by a narrow demographic. The threshold of leaving the street and going into a contemporary art space is still a huge barrier to opening up to new audiences and ideas, and Brathwaite-Shirley hopes that by creating such a place – between analogue and digital, between Liverpool and cyberpunk, between gallery and youth club – it may become a safe space to congregate, be, and take ownership. Beyond just being a fantastical backdrop, the plans are that it would also be home to events for the city’s youth, from card tournaments to drawing sessions.

The artist explains how such a space may be useful in helping foster agency and identity: “The kids all spoke about wanting to do things, but also about how constricting urban environments usually are – that usually rules are made for them, then they try and follow those rules in school or home or wherever. But this is their space, it’s no longer ours, that’s the whole point – I’m hoping the longer it goes on, the less it is about the show and the more it becomes a social space.”

This totalising situation is the creation of Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, who has designed the immersive urban space for her exhibition at FACT in Liverpool. While initially, the place may feel oppressive and uneasy, the longer a visitor dwells the more it becomes apparent that this is not a place to be feared so much as occupied and experienced, speaking to ideas that an ideal world does not need to be designed top-down, but might emerge from communities and peoples who inhabit and create it from within - however chaotic and cluttered it may read to those outside.

Brathwaite-Shirley’s exhibition, When Our Worlds Meet, grew out of conversations with such a community. Working with a collective of diverse and energised young people from the city, self-titled as The Bandidos, the artist asked simple worldbuilding questions: How would you redesign Liverpool for your community? What does your world need? What rules does your world have?

As an artist exploring fictional futures – of dystopian and utopian bent – Brathwaite-Shirley utilises video games within her practice, with a joyful punk approach to process and aesthetic. Self-declaring as creating “work that seeks to archive black trans experience,” her art is deliberately confrontational and frequently puts the visitor – or participatory gamer in a gallery context – into moments of awkwardness, self awareness, and shedding light onto privilege and status.

All the works in this show require engagement, physically with controllers to choose paths through text and images, but also mentally. Computer games differ from static, passively viewed artworks through their need to be activated and how the user becomes embodied within the avatar or agent represented on screen or responding to decisions. “With a game, you’re responsible for what you see and you’re responsible for what you don’t see – the amount of energy you put in is what you’ll get back from the work,” the artist shares, though then adds that the freedom of choice of possibility inherent within games is not always true, the artist playing with that notion of openness and control: “My main medium is the audience, because I want to move how they are thinking, looking, and feeling in the space – rather than them thinking they have control over the entire environment in the game because I often take control away, or give them just enough.”

This is not only true of gaming worlds though. The real worlds we inhabit – whether urban back-alley as presented in this gallery, or more polished environments from shopping centres to landscaped parks, also shape our agency, politics, and embodied sense of self. Architectures are built by and for certain bodies – usually white, male, heteronormative bodies – and through digital and gaming, Brathwaite-Shirley helps force an imagining of being in someone else’s world with less control, hoping to not only conjure a re-consideration of both self and place, but also help forge empathy.

The Bandidos and their reading of urban spaces are present throughout the installation. Over the course of a year, the artist ran workshops with the group under the creative auspices of forming a temporary video game company. “We would have conversations, drawing sessions, workshops, modelling sessions, so we could get a general gist so I could understand them and what they’re trying to say in the narrative,” the artist explains. The group then storyboarded ideas which Brathwaite-Shirley developed into the games which are spread across the exhibition, inviting interaction not only with the digital stories but also the constructed space itself.

Sitting on the swings a visitor looks up at a screen showing their experience of a rollercoaster. Text appears: THIS RIDE WAS NOT MADE FOR YOU, THIS RIDE WILL NOT LISTEN TO YOU, YOU FEEL LIKE YOU HAVE GIVEN UP CONTROL, BUT NOW YOU WANT IT BACK. In classic choose-your-own-adventure style, different paths can be taken, but whichever is chosen a reckoning with anything from self, politics, culture, and place will be needed to progress – while travelling cyber-gothic tracks through a world of polygon shapes and mapped textures, The Rollercoaster of Your Past asks questions about the self you once were, of your pride or embarrassment of yourself, and how that shaped who you are now or may become.

THERE ARE OVER 40,000 CHILDREN MINING FOR YOUR LEISURE, bold text shouts from the building site puddle. Then: ON YOUR WAY HOME YOU PASS A GROUP OF PEOPLE, AS YOU WALK BY ONE OF THEM BREAKS AWAY FROM THE GROUP AND BEGINS FOLLOWING YOU. These stories are forged from listening to the group over the workshops, then reimagining and fragmenting these range of thoughts into the artist’s individual recognisable aesthetic. But underneath the aesthetic there are a whole range of urban teenage concerns and observations from a disparate group of varied identities and personal stories.

“I feel like my job is to make sure all these disparate conversations come together in one space, because without that, it would be a mess – which I would kind of enjoy, but as I'm trying to build a new world that might exist for them, a mess is not what they need,” the artist explains. She adds that, “I usually describe myself as a mediation person during the process and then towards the end I’m a director, when I put it all together. Most of the process was just listening and not creating anything, just listening and listening and listening.”

Cities often design out the youth. Whether it’s hostile architecture to prevent congregation, a lack of spaces for teenagers to simply be without having to be consumers, or more aggressive tactics such Public Space Protection Orders or even sonic devices which emit alarms so high-pitched only dogs and younger ears can hear, designed to create youth-free spaces. Added to that, over the last decade youth clubs and spaces have closed down across the country due to underfunding. “When I was younger, I used to go to a youth club, but my youth club closed down as well,” Brathwaite-Shirley explains, sarcastically adding, “because our government is great.”

The exhibition exists as a kind of youth club, in lieu of those destroyed by Conservative decisions. Free to visit, the artist wants the city’s youth to take ownership, explaining that “the aim was to create a little city space that will be used by them.” Before the show opened to the art-loving, grown-up public, the kids were let in first to improve and personalise the space. The artist goes on, “every weekend, more kids from Liverpool will do that, so by the end of the show it should all look different - I want them to be able to graffiti and create something that will start fuck up the space, taking over. The rule I'm setting is that any young person who wants to come in and practice space is allowed to, I want the space to be theirs and for them to stamp their claim on it.”

Despite decades of outreach, a changing landscape of art appreciation, and ongoing work around what art is and who it’s for, galleries are still predomenantly populated by a narrow demographic. The threshold of leaving the street and going into a contemporary art space is still a huge barrier to opening up to new audiences and ideas, and Brathwaite-Shirley hopes that by creating such a place – between analogue and digital, between Liverpool and cyberpunk, between gallery and youth club – it may become a safe space to congregate, be, and take ownership. Beyond just being a fantastical backdrop, the plans are that it would also be home to events for the city’s youth, from card tournaments to drawing sessions.

The artist explains how such a space may be useful in helping foster agency and identity: “The kids all spoke about wanting to do things, but also about how constricting urban environments usually are – that usually rules are made for them, then they try and follow those rules in school or home or wherever. But this is their space, it’s no longer ours, that’s the whole point – I’m hoping the longer it goes on, the less it is about the show and the more it becomes a social space.”

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley works in animation, sound, performance, and video games. Her practice records the lives of Black Trans people, intertwining reality and fiction to create participatory work. In 2021 Brathwaite-Shirley was a resident artist at Wysing Arts Centre in South Cambridgeshire, UK. Her work has been shown at Science Gallery London, UK (2020); David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (2020); and arebyte Gallery, London, UK (2021), among many others.

www.daniellebrathwaiteshirley.com

FACT is the UK’s leading centre for art, film and the creative use of technology. Located in the heart of Liverpool

city centre, FACT creates transformative experiences that spark the imagination and enrich lives. Home to three art galleries, four cinema screens and a Studio/Lab for artists, the centre provides platforms and opportunities for

people to create, learn, experience and make sense of the world today. In 2023, FACT celebrates 20 years of

groundbreaking moments and unforgettable memories shaped by over 500 artists and more than 5 million

visitors.

www.fact.co.uk

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.fact.co.uk

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

When Our Worlds Meet (2022) by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley is on at FACT, Liverpool, until 9 April, exhibited alongside When the moon dreamed of the ocean (2022), a video installation by Josèfa Ntjam.

For more details visit:

www.fact.co.uk/event/danielle-brathwaite-shirley-jos%C3%A8fa-ntjam

images

All photos courtesy of FACT, Liverpool and © Rob Battersby

publication date

11 February 2023

tags

The Bandidos, Bus stop, Computer, Cyberpunk, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Cities, Digital, Environment, FACT, Games, Immersive, Liverpool, Mediation, Participation, Politics, Rollercoaster, Swings, Urban, Video games, Youth, Youth club

For more details visit:

www.fact.co.uk/event/danielle-brathwaite-shirley-jos%C3%A8fa-ntjam