Melting into air: Ann Veronica Janssens at Pirelli HangarBicocca

In a vast exhibition at Pirelli HangarBicocc, Milan, artist Ann Veronica Janssens explores how to melt modernity into a more fragile way of thinking of space & material. Will Jennings explores her series of installations, interventions & films which speak to the artist’s five decades of testing perception & form.

Pirelli HangarBicocca is not a small space. The enormous 1950s-60s

shed once used to test high-powered machinery consists of a nave with two

aisles, sitting within a district once comprising 200,000m² of factory buildings

producing railway carriages and farm machinery, but which since the mid-1980s

has transformed into a district of university, administration, culture

buildings, and new residential. The HangarBicocca towers over it all, a

dominating presence and a space which since 2004 has been one of the largest

exhibition spaces in Europe, presenting a series of temporary installations

from artists including Carsten Höller, Christian Boltanski, Maurizio Cattelan, and

Lucy and Jorge Orta as well as, within one of its aisles, five of Anselm

Kiefer’s immense stacked towers.

The area and hangar take their name from a 15th century country villa, the Bicocca degli Arcimboldi, which still sits within the broader Pirelli site, but instead of luxuriating within a rural setting is now hemmed in by industry and a sports stadium. In English, the word Bicocca translates as a small castle in an elevated setting, and externally the villa has some architectural typology of a fortress, projecting strength. It was, however, constructed as a country residence for the Arcimboldi family, and so internally it was altogether more domestic and decorative, still with historic frescoes showing the leisure and occupation of court ladies from performing and dancing to music, playing chess, or preparing the wedding bed, with the exemplary textiles, hairstyles, and bodily poise of the day.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The main space of HangarBicocca, the Navate, is 30 metres in height across a 9,500m² area, a scale of exhibition space within which it would be easy to lose artworks in even it were not entirely blacked out into an depthless void. It is a challenging space to show art within, just as Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall can be, with artists having to contend with a scale which art rarely has to contend with. The latest artist to work with the hangar is Ann Veronica Janssens, an artist who since the early 1980s has explored sensorial perception to colour, light, sound, and space but whose work is profoundly delicate and intimate – qualities which may not seem to easily fit within the industrial magnitude of the venue.

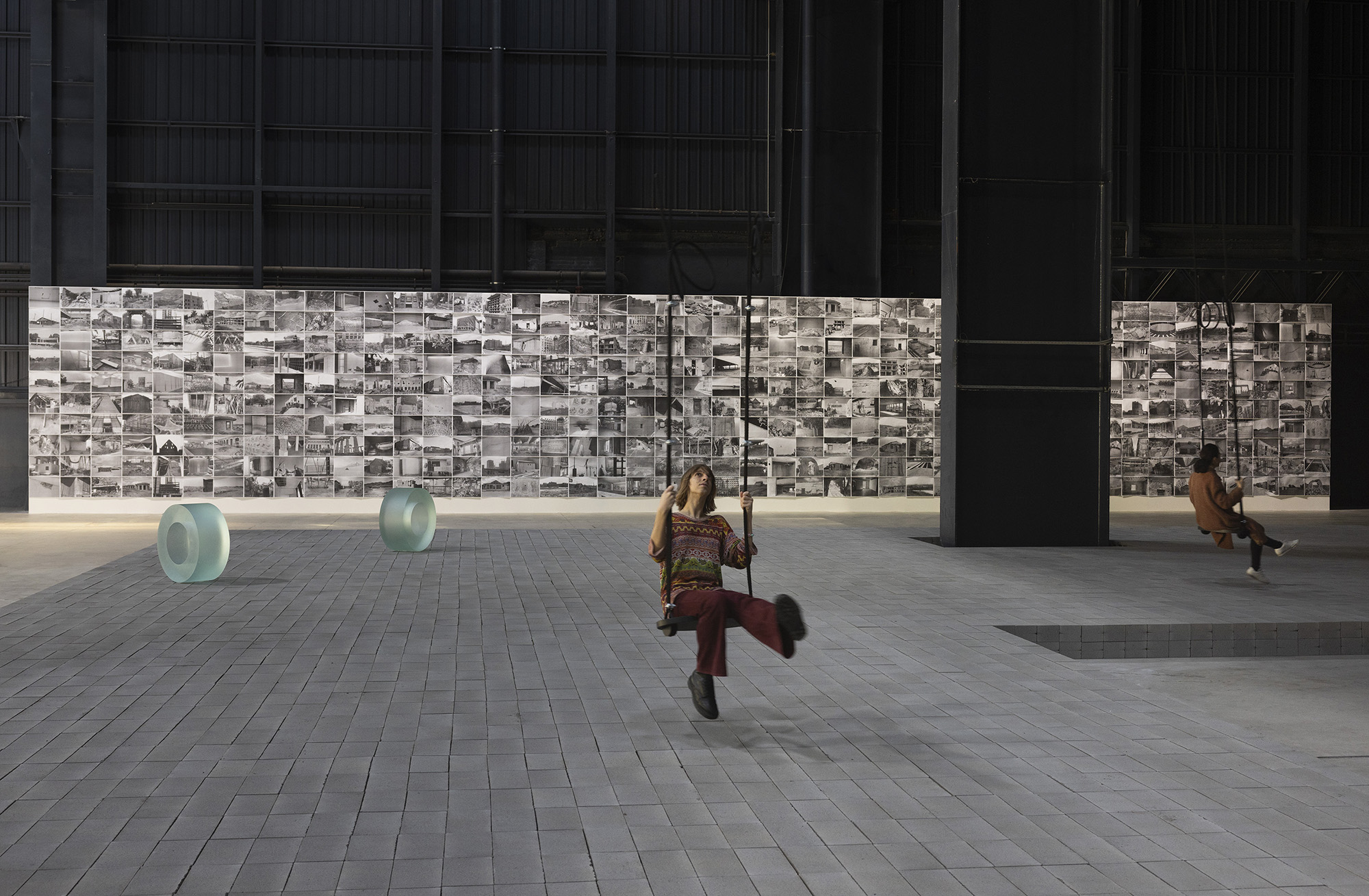

In a curation by Roberta Tenconi, however, individual works are not lost in expanse but find their place in a constellation of moments the visitor finds their own path through. There is, however, a start and end point, both works the artist made in the 1990s. It all begins with a wall of 460 photocopied A2 images, a Becher-like grid of ephemeral constructions, but where Bernd and Hiller rigidly recorded strong industrial forms, Jansenns’ are altogether more precarious and delicate. Discovered across her travels, these architectures are the antithesis of the Becher’s western monoliths, documenting unfinished looking buildings: self-made structures formed of salvaged material, abandoned concrete shells, bivouacs made of foliage, ad hoc assemblages built atop existing houses.

![]()

![]()

Figs.iv,v

For an artist deeply interested in the play between built and experiential space, architecture is at the heart of the project – whether that of the hangar or of a deconstructed understanding within individual works. For most exhibitions, the hangar is usually in pitch blackness, but here the artist has interrupted the void by opening up selected skylights to send shafts of light into the nave – not only forming geometric forces of quasi-religious strength, but also bringing life to the various works on show of colour and materiality which dance and sing in the light.

In a simply-conceived but physically-activated gesture a vast area of the Navate’s floor is raised with a vast double-layer grid of breeze blocks, an expanded Carl Andre which seems to monochromatically sink into the floor, but fill the space. Elsewhere, a single 12-metre long steel I-beam lays inert, but its top surfaced polished to a mirror, bouncing back the light shooting from above. Other discrete sculptural objects also capture and reimagine flitting daylight: mirrored circles sit on the floor like a series of wells suggesting a depth matching the 30-metre height of the space; immaculate glass circles sit as if they have just come to stop after rolling into the space, relaying light in all directions; aquarium-like cubes containing paraffin oil and water create impossible geometries of light, reflection, and refraction.

![]()

![]()

Figs.vi,vii

Hanging between them all is Golden Section (2009), a large and crumpled sheet of mirror foil, wafting with the air coming through opened doors and as visitors pass by. It was a work originally created with the artist Michel François during the creation of a choreography created and performed by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Further along, two leaning rectangles similarly shimmer in light. From her ongoing Magic Mirrors series, shattered safety glass is sandwiched between dichroic glass and Gelatin filters. These foil and glass pieces read as though contemporary twists of the Bicocca degli Arcimboldi frescoes, and similarly bringing decoration, drama, and feminine movement to an otherwise masculine and heavy architecture.

In early April, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker – an artist Janssens has collaborated with on many occasions – performed a new choreography in and relating to the installation. Pioverà, set to Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain (1965), explored how the body can fall in and out of sync with an environment. There is another bodily dance, of a kind, in the space. A large screen has projected upon it Janssens’ 2009 film Oscar, a close-up of Oscar Niemeyer slowly and silently smoking a cigar at the age of 102. It is an intimate presence, the smoke swirling in tune to his inner-thoughts. Elsewhere the artist has transfigured solid architectural components into a delicate fragility and subtlety, but here it is the pre-eminent architect of iconic and solid modernism who appears this way.

![]()

![]()

Figs.viii,ix

The exhibition ends with a call-back to the smoke exhaled by Niemeyer. A room at the end of the Navate is 13 x 22 metres, but the entering visitor would have no sense of geometry, scale, or space. As a counterpoint to the vast blackness of the main hall, MUHKA, Anvers (1992-2023) is a space full of artificial fog. Nervously shuffling into the silent whiteness, the only orientation offered for a visitor is a gentle chromatic gradient, a glass wall to the outside at the rear of the room allowing a barely perceivable shift to the colour of the fog as it is passed through.

As Marshall Berman via Karl Marx identified, “all that is solid melts into air,” and with this arrangement of works confidently arrayed across Pirelli HangarBicocca’s immensity, an assumed understanding of solidity, materiality, and modernist certainties is left as an open question. The graceful movement and folds of fabric in the frescoes of the nearby villa Bicocca degli Arcimboldi, from which the art venue takes its name, are more than decoration. They are all-encompassing artistic acts to break down the solidity of the fortress architecture, and through it the patriarchal, economic, and violent systems which led to its construction and form – systems as present in the 15th century as within the 20th century modernism tested by Ann Veronica Janssens.

![]()

![]()

Figs.x,xi

The area and hangar take their name from a 15th century country villa, the Bicocca degli Arcimboldi, which still sits within the broader Pirelli site, but instead of luxuriating within a rural setting is now hemmed in by industry and a sports stadium. In English, the word Bicocca translates as a small castle in an elevated setting, and externally the villa has some architectural typology of a fortress, projecting strength. It was, however, constructed as a country residence for the Arcimboldi family, and so internally it was altogether more domestic and decorative, still with historic frescoes showing the leisure and occupation of court ladies from performing and dancing to music, playing chess, or preparing the wedding bed, with the exemplary textiles, hairstyles, and bodily poise of the day.

Fig.i,ii,iii

The main space of HangarBicocca, the Navate, is 30 metres in height across a 9,500m² area, a scale of exhibition space within which it would be easy to lose artworks in even it were not entirely blacked out into an depthless void. It is a challenging space to show art within, just as Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall can be, with artists having to contend with a scale which art rarely has to contend with. The latest artist to work with the hangar is Ann Veronica Janssens, an artist who since the early 1980s has explored sensorial perception to colour, light, sound, and space but whose work is profoundly delicate and intimate – qualities which may not seem to easily fit within the industrial magnitude of the venue.

In a curation by Roberta Tenconi, however, individual works are not lost in expanse but find their place in a constellation of moments the visitor finds their own path through. There is, however, a start and end point, both works the artist made in the 1990s. It all begins with a wall of 460 photocopied A2 images, a Becher-like grid of ephemeral constructions, but where Bernd and Hiller rigidly recorded strong industrial forms, Jansenns’ are altogether more precarious and delicate. Discovered across her travels, these architectures are the antithesis of the Becher’s western monoliths, documenting unfinished looking buildings: self-made structures formed of salvaged material, abandoned concrete shells, bivouacs made of foliage, ad hoc assemblages built atop existing houses.

Figs.iv,v

For an artist deeply interested in the play between built and experiential space, architecture is at the heart of the project – whether that of the hangar or of a deconstructed understanding within individual works. For most exhibitions, the hangar is usually in pitch blackness, but here the artist has interrupted the void by opening up selected skylights to send shafts of light into the nave – not only forming geometric forces of quasi-religious strength, but also bringing life to the various works on show of colour and materiality which dance and sing in the light.

In a simply-conceived but physically-activated gesture a vast area of the Navate’s floor is raised with a vast double-layer grid of breeze blocks, an expanded Carl Andre which seems to monochromatically sink into the floor, but fill the space. Elsewhere, a single 12-metre long steel I-beam lays inert, but its top surfaced polished to a mirror, bouncing back the light shooting from above. Other discrete sculptural objects also capture and reimagine flitting daylight: mirrored circles sit on the floor like a series of wells suggesting a depth matching the 30-metre height of the space; immaculate glass circles sit as if they have just come to stop after rolling into the space, relaying light in all directions; aquarium-like cubes containing paraffin oil and water create impossible geometries of light, reflection, and refraction.

Figs.vi,vii

Hanging between them all is Golden Section (2009), a large and crumpled sheet of mirror foil, wafting with the air coming through opened doors and as visitors pass by. It was a work originally created with the artist Michel François during the creation of a choreography created and performed by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Further along, two leaning rectangles similarly shimmer in light. From her ongoing Magic Mirrors series, shattered safety glass is sandwiched between dichroic glass and Gelatin filters. These foil and glass pieces read as though contemporary twists of the Bicocca degli Arcimboldi frescoes, and similarly bringing decoration, drama, and feminine movement to an otherwise masculine and heavy architecture.

In early April, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker – an artist Janssens has collaborated with on many occasions – performed a new choreography in and relating to the installation. Pioverà, set to Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain (1965), explored how the body can fall in and out of sync with an environment. There is another bodily dance, of a kind, in the space. A large screen has projected upon it Janssens’ 2009 film Oscar, a close-up of Oscar Niemeyer slowly and silently smoking a cigar at the age of 102. It is an intimate presence, the smoke swirling in tune to his inner-thoughts. Elsewhere the artist has transfigured solid architectural components into a delicate fragility and subtlety, but here it is the pre-eminent architect of iconic and solid modernism who appears this way.

Figs.viii,ix

The exhibition ends with a call-back to the smoke exhaled by Niemeyer. A room at the end of the Navate is 13 x 22 metres, but the entering visitor would have no sense of geometry, scale, or space. As a counterpoint to the vast blackness of the main hall, MUHKA, Anvers (1992-2023) is a space full of artificial fog. Nervously shuffling into the silent whiteness, the only orientation offered for a visitor is a gentle chromatic gradient, a glass wall to the outside at the rear of the room allowing a barely perceivable shift to the colour of the fog as it is passed through.

As Marshall Berman via Karl Marx identified, “all that is solid melts into air,” and with this arrangement of works confidently arrayed across Pirelli HangarBicocca’s immensity, an assumed understanding of solidity, materiality, and modernist certainties is left as an open question. The graceful movement and folds of fabric in the frescoes of the nearby villa Bicocca degli Arcimboldi, from which the art venue takes its name, are more than decoration. They are all-encompassing artistic acts to break down the solidity of the fortress architecture, and through it the patriarchal, economic, and violent systems which led to its construction and form – systems as present in the 15th century as within the 20th century modernism tested by Ann Veronica Janssens.

Figs.x,xi

Ann Veronica Janssens' work has been featured in solo

exhibitions at institutions of international importance, including Louisiana

Museum of Modern Art Humlebæk and South London Gallery (2020); Musée de

l'Orangerie, Paris (2019); Baltimore Museum of Art, De Pont, Tilburg, Kiasma

Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki (2018); IAC – Institut d'art contemporain

– Villeurbanne/Rhône-Alpes (2017); Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas (2016);

Wellcome Collection, London (2015); Ausstellungshalle Zeitgenössiche Kunst, Münster,

CRAC Alsace - centre rhénan d'art contemporain, Altkirch (2011); WIELS,

Brussels, Espai d'Art Contemporani de Castellò, Castellón (2009); Museum

Mosbroich, Leverkusen (2007); Kunsthalle Bern, Bern, Musée d'Orsay, Paris, CCAC

Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco (2003); Neue

Nationalgalerie, Berlin (2001). The artist has participated in major

international exhibitions—including Sharjah Biennial 14 (2019); Manifesta 10,

St. Petersburg (2014); Biennale of Sydney (1998 and 2012); Biennale de Lyon

(2005); and Bienal de São Paulo (1994)—as well as group exhibitions in

institutions such as Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna; SMAK, Ghent; Grand Palais, Paris;

Punta della Dogana, Venice (2019); Hayward Gallery, London (2018); Mudam,

Luxembourg, Sprengel Museum, Hannover, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Buenos

Aires (2015); Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2014); Fundació Juan Miró, Barcelona

(2013). In 1999 she represented Belgium (with Michel François) at the 48th

Venice Biennale.

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.willjennings.info

visit

Grand Bal, by Ann Veronica Janssens, is exhibited at Pirelli

HangarBicocca until 30 July 2023.

More information available at: www.pirellihangarbicocca.org/en/exhibition/ann-veronica-janssens

images

fig.i

Pirelli

HangarBicocca. Photo Lorenzo Palmeri. Courtesy Pirelli HangarBicocca

figs.ii,iii Frescoes at the Bicocca degli Arcimboldi. ©

LombardiaBeniCultural. Available at: www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture/schede/3o100-00001

fig.iv,v,vi,x Ann Veronica Janssens, Grand Bal, exhibition view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2023.

© 2023 Ann Veronica Janssens / SIAE

Photo Andrea Rossetti.

fig.vii Ann Veronica Janssens, Magic Mirrors (Pink & Blue) (2013-2023) (detail).

Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2023

Courtesy the artist and Alfonso Artiaco, Naples. © 2023 Ann Veronica Janssens / SIAE.

Photo Andrea Rossetti.

figs.viii,ix Pioverà, choreography by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker inside the exhibition Grand Bal, by Ann Veronica Janssens, Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2023.

Courtesy Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker; Ann Veronica Janssens and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan. © 2023 Ann Veronica Janssens / SIAE.

Photo Andrea Rossetti.

fig.xi Ann Veronica Janssens, MUHKA, Anvers (1997-2023). Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2023. Collection 49 Nord 6 Est – Frac Lorraine.

© 2023 Ann Veronica Janssens / SIAE. Photo Andrea Rossetti.

publication date

19 June 2023

tags

Carl Andre, Architecture, Marshall Berman, Bernd and Hiller Becher, Bicocca degli Arcimboldi, Colour, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Factory, Fog, Michel François, Fresco, Geometry, Glass, I-beam, Industry, Installation, Ann Veronica Janssens, Will Jennings, Anselm Kiefer, Light, Karl Marx, Material, Mirror, Modernism, Oscar Niemeyer, Pirelli HangarBicocca, Steve Reich, Smoke, Solidity, Sound

More information available at: www.pirellihangarbicocca.org/en/exhibition/ann-veronica-janssens