The poetry

of everything: Massimo Bartolini’s musical scaffolding

A grid of scaffolding snaking around an Italian art gallery may seem inconsequential, as if the next exhibition is being installed. In fact, it’s the work of artist Massimo Bartolini & instead of standing inert, it’s a poetic musical instrument from which a Gavin Bryars composition emerges, as Robert Barry discovers.

“Organ

pipes…” Massimo Bartolini tells me with a sigh, “are complicated.” The sounding

tubes of a pipe organ like the one you might find in your local church tend

still to be handmade out of flat metal sheets, following much the same

techniques as they have for centuries. The precise solution of different

elements in the alloy must be exactly calibrated since tiny deviations in the

amount of tin or lead or copper or zinc can distort the resulting sound. The

solder used to shape and join those sheets has to be just the right

temperature: too cool and the solder won’t set, too hot and it’ll melt through

the metal. On top of that, the flow of air pumped through the finished pipes

must be at just the right pressure: too low and you get pitch fluctuations

– or even no sound at all – but if the pressure is too high, the note is

overblown and you end up with no more than a thin whistling screech. This

becomes especially tricky if, like Bartolini, your organ pipes are

seventy-seven metres long and span across seven different rooms of a vast

exhibition space in the north of Tuscany.

Visiting the Centro per l'Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci in Prato earlier this year, at first glance you might have thought the galleries were still under construction. The white-walled rooms bisected by a sprawling network of scaffolding tubes, like a suspiciously tidy building site, still there were no sounds of drilling or hammering or cat-calling labourers. Instead, the air was filled with an ever-shifting tapestry of tones and drones, a rich composition that would drift through the space like thick smoke billowing through a burning building. The scaffolding Bartolini installed here is no ordinary scaffolding, it is his installation sound work In là (2022). Hiding within its structure lurks an organ, the poles acting as its pipes, playing music specially composed for a work by Gavin Bryars.

![]()

Working with Bryars, Bartolini tells me, was “a dream I have had for decades.” As a student, he would listen repeatedly to the album Hommages that the English composer made for cult Belgian label Les Disques de Crépuscule in 1981 – especially its dreamy opening tribute to Bill Evans: My First Homage. “Gavin is a person who knows about art,” Bartolini says, “unlike so many musicians who are really ignorant about art (while artists know a lot about music). So, he immediately understood the material part of the work.” Since the sculpture itself is so big that no position offers the viewer a perspective on the whole work, Bryars immediately decided, “ok, if you never see the completeness of the sculpture, you will never hear the completeness of the music.” The composer ended up creating a different score for each room, all controlled by huge music-box-like wheel at the heart of the instrument. “So, when I am in room number three, I can’t hear room number seven, but I can hear a little bit of room number four and maybe a little bit less of room number five,” Bartolini explains, adding that “it’s the position of the public that makes the piece.”

There is no possibility of passive spectatorship here. Music and audience exist in a shared dynamic ecosystem, as Bartolini emphasises: “you are there in the room, breathing your air and the organ catches your air and blows it into the pipes and makes a note and then you breath back again the air of that note. You breathe a note, and it makes a note out of your breath – because you are close! You are there!” It’s true that is rare to find oneself so embedded in the guts of such an instrument. Once, interviewing the Irish experimental musician Áine O'Dwyer, she took me into the organ loft, up amongst the pipes, at the church of St. John-at-Hackney. There, as she stabbed at chords and picked out notes, I felt a huge rush of air engulfing me, like being caught in the respiratory tract of some great beast. Bartolini, likewise, describes his sculpture, as “an extra lung.”

![]()

There is a rich history of organ building in Prato and nearby Pistoia, stretching back over five-hundred years. Matteo da Prato, born in the city in 1391, was amongst the earliest secular craftsmen in an industry formerly dominated by monks. The monumental sculpture Cantoria by Donatello was originally built to sit at the head of the organ Matteo constructed for the Duomo in Florence. Bartolini was pleased to draw on this tradition, employing local artisans, Massimo Drovandi, Samuele Maffucci, Samuele Frangioni, and Yari Mazza to fabricate his instrument.

This is also not the first organ the artist has created. Since his earliest works in the late 80s, sound has consistently played a major role in the artist’s oeuvre. He first conceived of the connection between scaffolding and pipe organs in 2008, seeing both as “objects that are intended to cover distances,” in terms of the spatial dissemination of sound waves in space, in the case of the latter, or the modular segmentation of a building’s height and expanse, in the case of the former. In that year, he exhibited a work, Organi, consisting of six levels of scaffolding that played a series of variations on John Cage’s Cheap Imitation (1969) at Massimo di Carlo in Milan. In 2017, a monographic show at Fondazione Merz (also in Milan) brought together several of these works under one roof. But Bartolini sees his collaboration with Gavin Bryars as “the most ambitious” of the series.

![]()

It is not just the vast scale of the work that makes it, in Bartolini’s eyes, the most replete of his organs. By suspending the scaffold a few centimetres from the ground, he sees it as attaining a sort of “weightlessness”; while the music, by contrast, feels more embodied, more physical than ever. “So, the structure became lighter and the music becomes heavier and they find each other halfway,” he says with a smile.

Bartolini has an occultist’s eye for such symbolic resemblances. His eyes twinkle over the Zoom connection as he tells me about the specific semiotic resonances of each of his chosen materials: a particular metal for the scaffold poles, a certain wood for the cams, each with their own significance. Even the electromechanical valves in the organ pipes suggest, to him, an image of neurons firing in the brain. “Everything has a poetic side,” he says. “Material tells a story. There must be a reason, a poetical reason for every single thing. Nothing is innocent. They all have their legend. When you put materials next to each other you put together legends.”

![]()

![]()

Visiting the Centro per l'Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci in Prato earlier this year, at first glance you might have thought the galleries were still under construction. The white-walled rooms bisected by a sprawling network of scaffolding tubes, like a suspiciously tidy building site, still there were no sounds of drilling or hammering or cat-calling labourers. Instead, the air was filled with an ever-shifting tapestry of tones and drones, a rich composition that would drift through the space like thick smoke billowing through a burning building. The scaffolding Bartolini installed here is no ordinary scaffolding, it is his installation sound work In là (2022). Hiding within its structure lurks an organ, the poles acting as its pipes, playing music specially composed for a work by Gavin Bryars.

Working with Bryars, Bartolini tells me, was “a dream I have had for decades.” As a student, he would listen repeatedly to the album Hommages that the English composer made for cult Belgian label Les Disques de Crépuscule in 1981 – especially its dreamy opening tribute to Bill Evans: My First Homage. “Gavin is a person who knows about art,” Bartolini says, “unlike so many musicians who are really ignorant about art (while artists know a lot about music). So, he immediately understood the material part of the work.” Since the sculpture itself is so big that no position offers the viewer a perspective on the whole work, Bryars immediately decided, “ok, if you never see the completeness of the sculpture, you will never hear the completeness of the music.” The composer ended up creating a different score for each room, all controlled by huge music-box-like wheel at the heart of the instrument. “So, when I am in room number three, I can’t hear room number seven, but I can hear a little bit of room number four and maybe a little bit less of room number five,” Bartolini explains, adding that “it’s the position of the public that makes the piece.”

There is no possibility of passive spectatorship here. Music and audience exist in a shared dynamic ecosystem, as Bartolini emphasises: “you are there in the room, breathing your air and the organ catches your air and blows it into the pipes and makes a note and then you breath back again the air of that note. You breathe a note, and it makes a note out of your breath – because you are close! You are there!” It’s true that is rare to find oneself so embedded in the guts of such an instrument. Once, interviewing the Irish experimental musician Áine O'Dwyer, she took me into the organ loft, up amongst the pipes, at the church of St. John-at-Hackney. There, as she stabbed at chords and picked out notes, I felt a huge rush of air engulfing me, like being caught in the respiratory tract of some great beast. Bartolini, likewise, describes his sculpture, as “an extra lung.”

There is a rich history of organ building in Prato and nearby Pistoia, stretching back over five-hundred years. Matteo da Prato, born in the city in 1391, was amongst the earliest secular craftsmen in an industry formerly dominated by monks. The monumental sculpture Cantoria by Donatello was originally built to sit at the head of the organ Matteo constructed for the Duomo in Florence. Bartolini was pleased to draw on this tradition, employing local artisans, Massimo Drovandi, Samuele Maffucci, Samuele Frangioni, and Yari Mazza to fabricate his instrument.

This is also not the first organ the artist has created. Since his earliest works in the late 80s, sound has consistently played a major role in the artist’s oeuvre. He first conceived of the connection between scaffolding and pipe organs in 2008, seeing both as “objects that are intended to cover distances,” in terms of the spatial dissemination of sound waves in space, in the case of the latter, or the modular segmentation of a building’s height and expanse, in the case of the former. In that year, he exhibited a work, Organi, consisting of six levels of scaffolding that played a series of variations on John Cage’s Cheap Imitation (1969) at Massimo di Carlo in Milan. In 2017, a monographic show at Fondazione Merz (also in Milan) brought together several of these works under one roof. But Bartolini sees his collaboration with Gavin Bryars as “the most ambitious” of the series.

It is not just the vast scale of the work that makes it, in Bartolini’s eyes, the most replete of his organs. By suspending the scaffold a few centimetres from the ground, he sees it as attaining a sort of “weightlessness”; while the music, by contrast, feels more embodied, more physical than ever. “So, the structure became lighter and the music becomes heavier and they find each other halfway,” he says with a smile.

Bartolini has an occultist’s eye for such symbolic resemblances. His eyes twinkle over the Zoom connection as he tells me about the specific semiotic resonances of each of his chosen materials: a particular metal for the scaffold poles, a certain wood for the cams, each with their own significance. Even the electromechanical valves in the organ pipes suggest, to him, an image of neurons firing in the brain. “Everything has a poetic side,” he says. “Material tells a story. There must be a reason, a poetical reason for every single thing. Nothing is innocent. They all have their legend. When you put materials next to each other you put together legends.”

Massimo

Bartolini was born in

Cecina (1962), where he lives and works. He studied as a surveyor in Livorno

(1976–1981) and graduated from the Accademia di Firenze (1989). He teaches

visual arts at UNIBZ Bolzano, NABA (Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti, Milan) and

the Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna. Also following his experiences in the

world of theatre, Massimo Bartolini’s first works were performances involving

live music, theatre machinery and dancers. Thereafter he devoted himself

separately to installation and performance, thereby isolating the actors from

the theatrical machinery and the stage in order to create a space that directly

alters the viewers’ perceptions also through an architectural narrative.

Bartolini’s

typical attitude is one of extreme openness across mediums, which he uses and

reinvents in unorthodox ways. He uses an extraordinary variety of languages and

materials: from performance works involving temporary actors, the public or the

architectural space, to drawings produced over deliberately long periods of

time; from large public installations often created with the collaboration of

other hands and knowledge, to small sketch-works assembled in the studio; from

complex sound sculptures to photographs and videos. Bartolini is one of the

most internationally-known Italian artists. Since 1993, he has exhibited in

numerous solo and collective exhibitions in Italy and abroad.

Gavin

Bryars was born in

Yorkshire in 1943. His first musical reputation was as a jazz bassist working

in the early sixties with improvisers Derek Bailey and Tony Oxley. He abandoned

improvisation in 1966 and worked for a time in the United States with John

Cage. Subsequently he collaborated closely with composers such as Cornelius

Cardew and John White. From 1969 to 1978 he taught in departments of Fine Art

in Portsmouth and Leicester, and during the time that he taught at Portsmouth

College of Art he was instrumental in founding the legendary Portsmouth

Sinfonia. He founded the music department at Leicester Polytechnic (later De Montfort

University) and was professor of music there from 1986 to 1994. His first major

work as a composer was The Sinking of the Titanic (1969) originally

released on Brian Eno’s Obscure label in 1975 and Jesus’ Blood Never Failed

Me Yet (1971), both famously released in new versions in the 1990s on Point

Music label, selling over a quarter of a million copies. The original 1970s

recordings have been re-released on CD by GB Records.

www.gavinbryars.com

Robert

Barry is a freelance

writer and musician based in London. His most recent book, Compact Disc,

was published by Bloomsbury in 2020.

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

www.gavinbryars.com

Robert

Barry is a freelance

writer and musician based in London. His most recent book, Compact Disc,

was published by Bloomsbury in 2020.

www.writingbyrobertbarry.tumblr.com

listen & buy

In là by Gavin Bryars and Massimo Bartolini is published

by Alga Marghen and available on vinyl in a numbered edition of 400 from boomkat.

More information available at:

www.boomkat.com/products/in-la

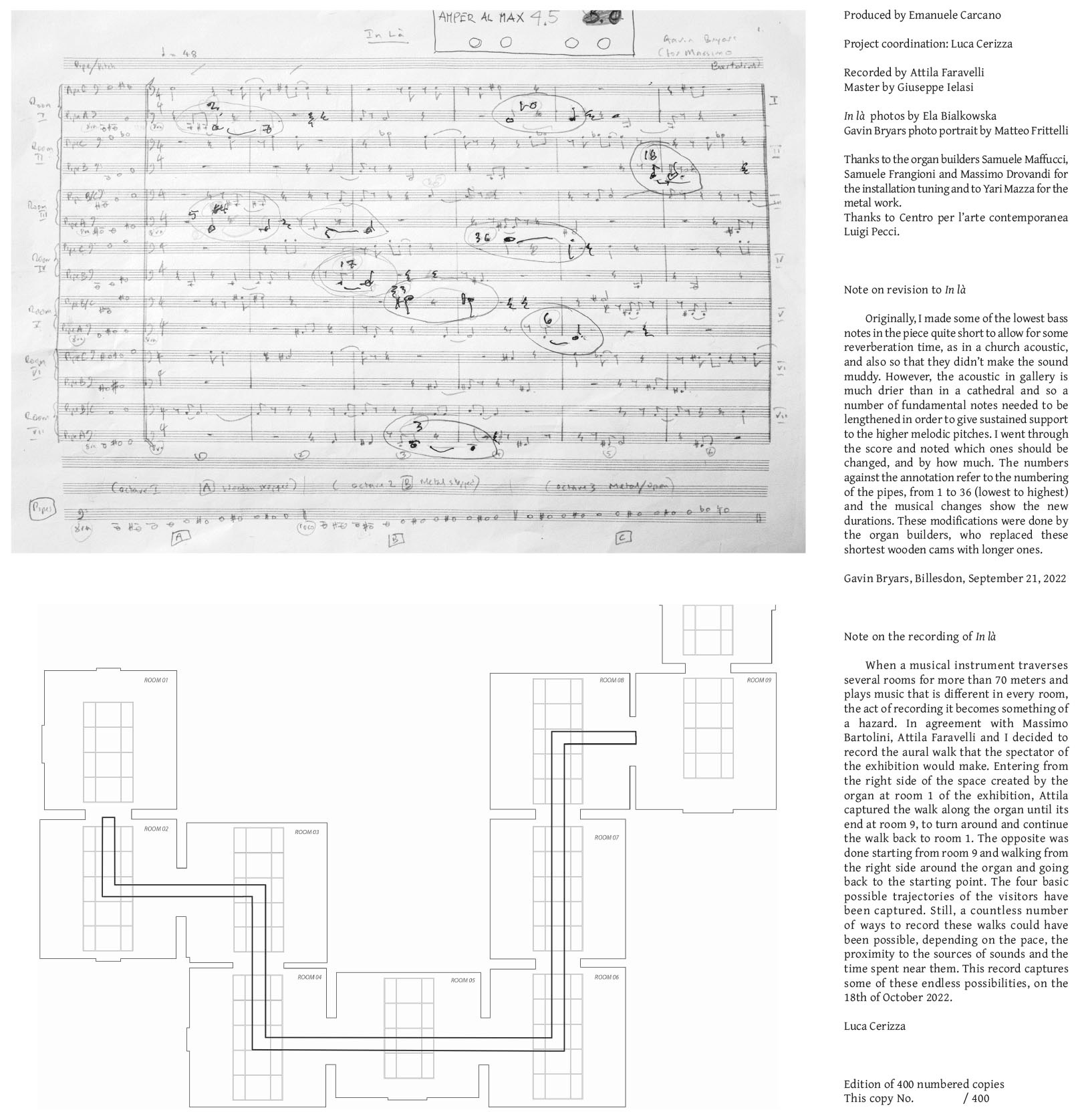

An art edition of the

LP, in an edition of 90 numbered copies in die-cut sleeve with a signed score

by Gavin Bryars and an original engraving by Massimi Bartolini is available

from Soundohm here:

www.soundohm.com/product/in-la-lp-1

images

installation images Courtesy

Centro per l'Arte

Contemporanea Luigi Pecci. © Ela Bialkowska OKNO studio.

album images Courtesy & ©

Alga Marghen.

publication date

20 June 2023

tags

Alga Marghan, Robert Barry, Massimo Bartolini, Gavin Bryars, John Cage, Centro per l'Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Composition, Installation, Matteo da Prato, Massimo Drovandi, Samuele Frangioni, Fondazione Merz, Samuele Maffucci, Massimo di Carlo, Yari Mazza, Music, Music box, Áine O'Dwyer, Organ, Pipes, Scaffolding, Sculpture, Sound art, Wind, Wind instrument

www.boomkat.com/products/in-la

An art edition of the LP, in an edition of 90 numbered copies in die-cut sleeve with a signed score by Gavin Bryars and an original engraving by Massimi Bartolini is available from Soundohm here: www.soundohm.com/product/in-la-lp-1