Seeing Things:

how artists

use Instagram

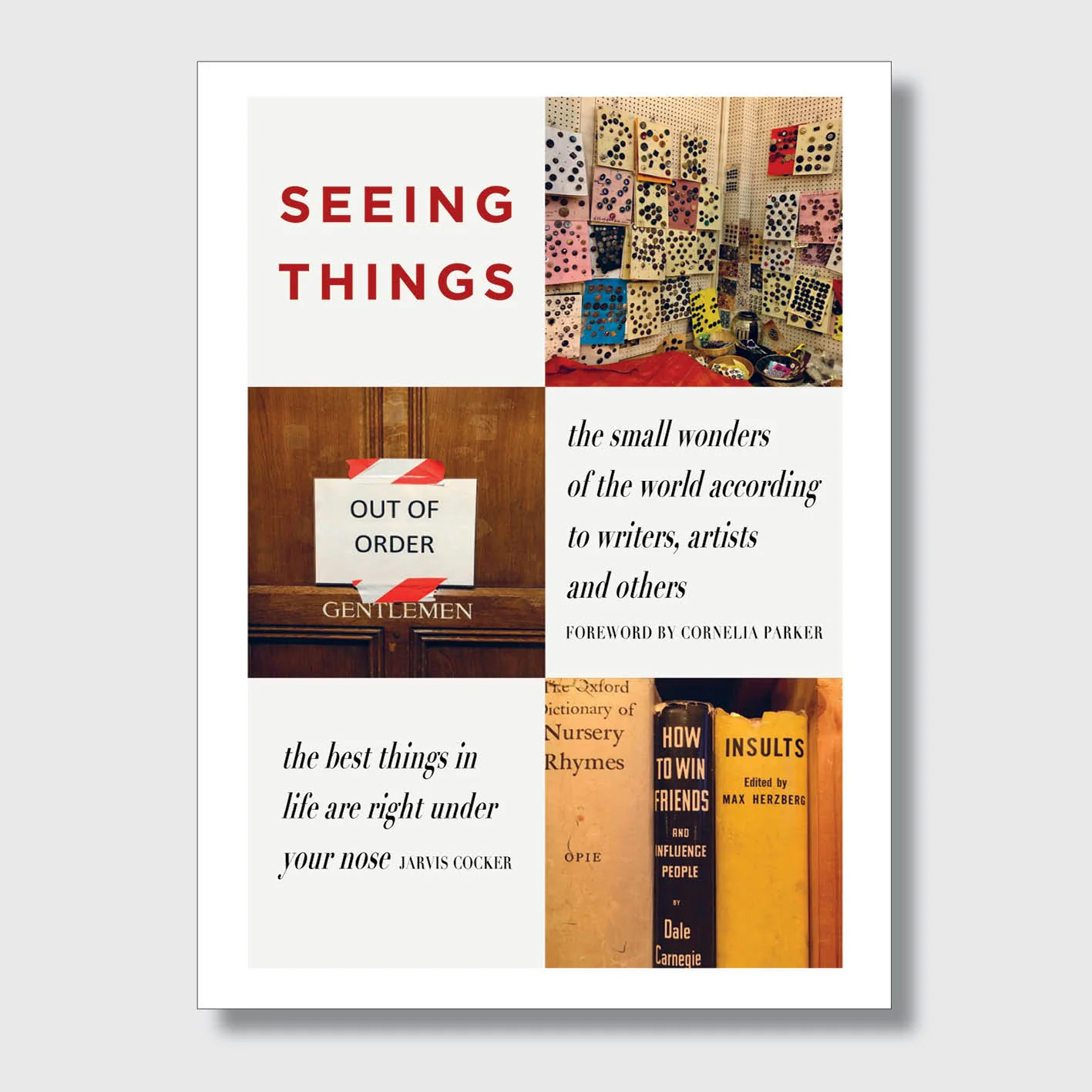

A new book from independent arts publisher Redstone Press looks

at how creatives use Instagram to document how they see the world. Always

looking for poetry, accident, quirk, or political moments in the everyday world

surrounding us, an artist’s Instagram page can become a diary of looking.

How do artists see the world? We know what they do to the

world, how they represent, reconfigure, reimagine, or play with it, but how do they actually see the world around them before they transform it into their idea? After all, do all of us – artists or otherwise – not see the same? Seeing

Things, a new book from independent publisher Redstone Press curates the

artists’ gaze, extracting images and words from celebrated creatives on

Instagram to create a flickable-archive on how artists see the world.

![]()

Over thirty artists have been approached to present selected images and comments. Documenting the momentary and throwaway moments of passing through the world that to most of us may be oblique observations or even go unnoticed, but to a creative mind can become ingredient into the great mental mixing pot of idea. Alongside, small texts by poet Charles Boyle add a secondary artistic refraction.

Take, for example, Richard Wentworth and his detail of a protected piece of architecture, below. Presumably from a near-completed development, some gaffer tape and padding protects a threshold detail, the kind of delicate touch upon the built environment we pass countless times every day, but to an artist such as Wentworth – deeply interested in material, architecture, and gesture – becomes more than building-site action and transforms into symbolism.

![]()

Many of the images are from the street, observing across thresholds into commercial or private spaces from the public domain, watching others who share the civic space, or the discovery of incongruous interruptions into the public norm. Roz Chast, the New Yorker cartoonist, chances upon an abandoned gas oven, topped with a fairly-fresh white bouquet. Two moments of disposal, and million stories and possible histories unravel from the image.

Carey Young, an artist whose solo exhibition at Modern Art Oxford was featured in recessed.space (see 00099), captures commercial display from the public pavement. But her mind and vision is political, and the two sides of that glass threshold are not discrete and separate but inform one another. Young captures a British gentleman’s outfitters’ window, blue corduroy trousers slung like a scarf over an in-sale tweed jacket, while plastic roses seemingly protect this contrived and twee construct of a commercial, consumerist, patriarchal, and romanticised Britishness.

![]()

![]()

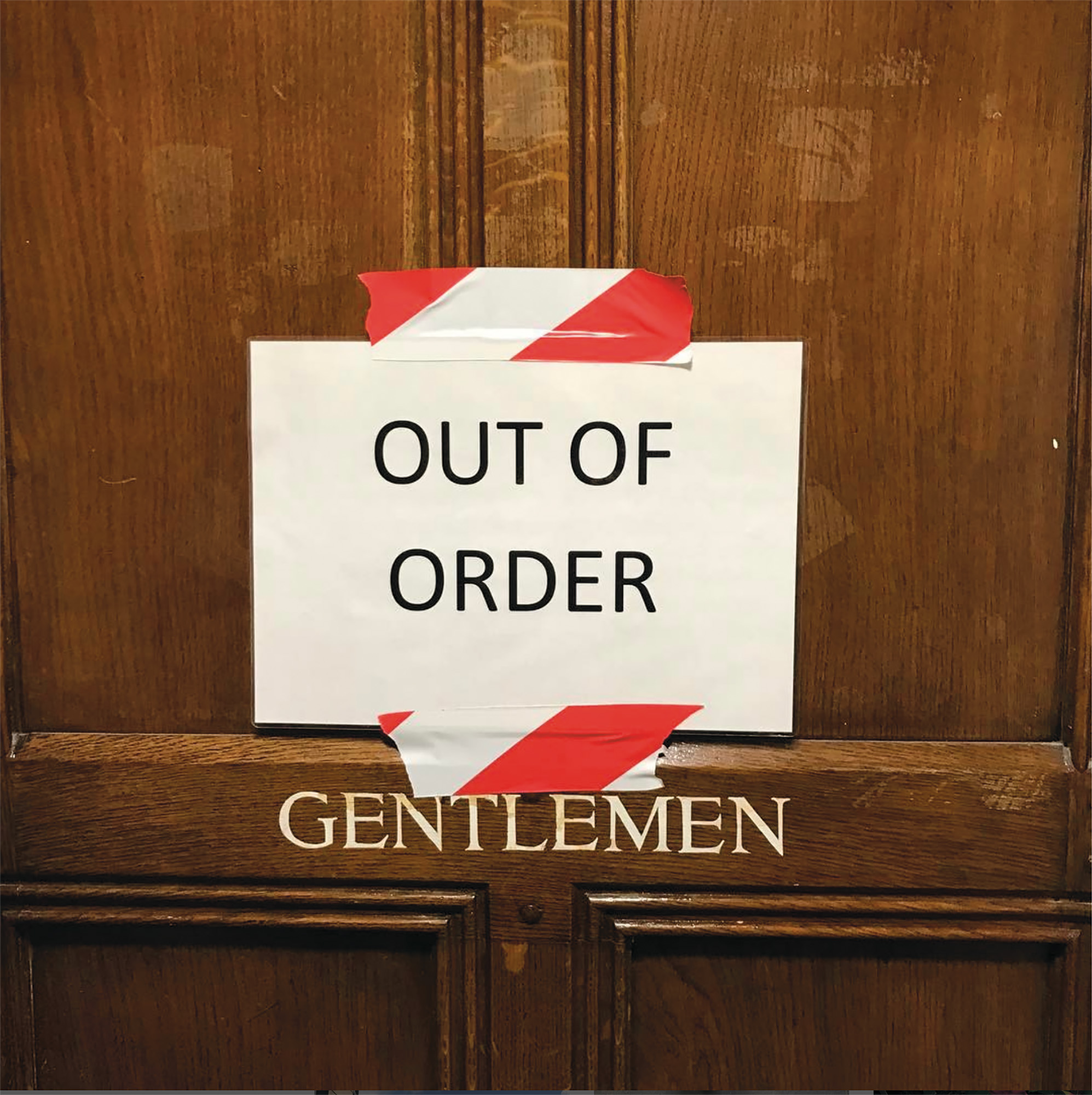

The artist Cornelia Parker (who also writes the book’s forward) channels some of Young’s gendered reading of the city. And so she should. The serif font “GENTLEMAN” upon an oak panelled toilet door is supplanted with an A4 “OUT OF ORDER” in the Word-default typeface Calibri, fixed with rudely cut tape. A political moment.

Scottish novelist Andrew O’Hagen sees a lady every day. Presumably on a daily walk, he sees her feed the pigeons, becoming as much a fixture of the repeating environment as the bollards, flagstones, lamppost, and urban architectures he perambulates. This day, however, her feeding occurred at the same moment a neighbour cat also entered the fray, a small-scale Hitchcockian scene ensuing. The photo itself is low quality, zoomed in with digital artefacts so we can read the feeling of the scene but no detail. But that is fine, and the point. These are snapshots of awareness, not composed masterpieces – though for all we know they may eventually feed into a chapter’s moment, an artistic project, or a song lyric.

![]()

![]()

The book departs the public to also enter the private domain of creativity. A top-down image from William Kentridge – subtitled with his quote “silence reigns supreme” – shows his working station, charcoal, ink, paper, and sketchbooks scattered across a desk. It’s partly performative, as all photography is at its heart, but also insight into process. A dirtier detail is presented by Jeff Wall via Dexter Dalwood. Wall’s Diagonal Composition (1993) is of the artist’s studio, carefully composed before being presented in a lightbox image shown at Tate Modern in London, presumably where Dalwood photographed it himself.

On the facing page of the spread is a contribution from singer Jarvis Cocker. As with Dalwood it is a rephotograph of another creative’s work and space, as the Pulp singer’s comment under the image reads: “Just been tidying my room … Only joking: this is an artwork called La Piece de Vie by Robert Combas. It features in an exhibition by the author Michel Houellebecq.”

In this image we see how the creative mind reads spaces and images. They collect, but credit, observe a history and provenance, but rearticulate it for a new idea. This is how photographic mediation works, and how Instagram has perpetuated its shareability and replicability. Seeing Things doesn’t so much critique this mediated power of the image, but offers an analogue continuation of the process.

![]()

![]()

Fig.i

Over thirty artists have been approached to present selected images and comments. Documenting the momentary and throwaway moments of passing through the world that to most of us may be oblique observations or even go unnoticed, but to a creative mind can become ingredient into the great mental mixing pot of idea. Alongside, small texts by poet Charles Boyle add a secondary artistic refraction.

Take, for example, Richard Wentworth and his detail of a protected piece of architecture, below. Presumably from a near-completed development, some gaffer tape and padding protects a threshold detail, the kind of delicate touch upon the built environment we pass countless times every day, but to an artist such as Wentworth – deeply interested in material, architecture, and gesture – becomes more than building-site action and transforms into symbolism.

Fig.ii

Many of the images are from the street, observing across thresholds into commercial or private spaces from the public domain, watching others who share the civic space, or the discovery of incongruous interruptions into the public norm. Roz Chast, the New Yorker cartoonist, chances upon an abandoned gas oven, topped with a fairly-fresh white bouquet. Two moments of disposal, and million stories and possible histories unravel from the image.

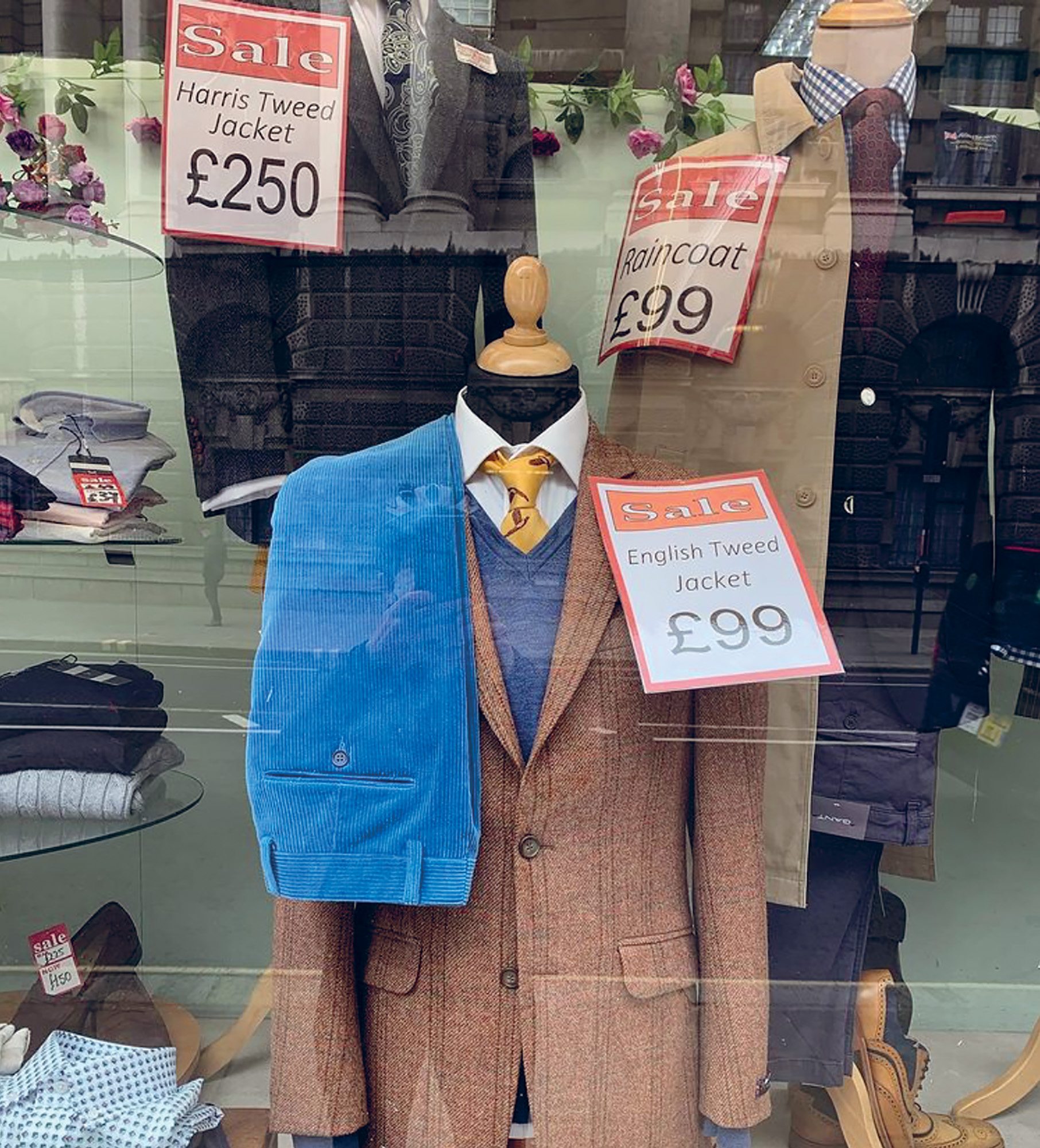

Carey Young, an artist whose solo exhibition at Modern Art Oxford was featured in recessed.space (see 00099), captures commercial display from the public pavement. But her mind and vision is political, and the two sides of that glass threshold are not discrete and separate but inform one another. Young captures a British gentleman’s outfitters’ window, blue corduroy trousers slung like a scarf over an in-sale tweed jacket, while plastic roses seemingly protect this contrived and twee construct of a commercial, consumerist, patriarchal, and romanticised Britishness.

Figs.iii,iv

The artist Cornelia Parker (who also writes the book’s forward) channels some of Young’s gendered reading of the city. And so she should. The serif font “GENTLEMAN” upon an oak panelled toilet door is supplanted with an A4 “OUT OF ORDER” in the Word-default typeface Calibri, fixed with rudely cut tape. A political moment.

Scottish novelist Andrew O’Hagen sees a lady every day. Presumably on a daily walk, he sees her feed the pigeons, becoming as much a fixture of the repeating environment as the bollards, flagstones, lamppost, and urban architectures he perambulates. This day, however, her feeding occurred at the same moment a neighbour cat also entered the fray, a small-scale Hitchcockian scene ensuing. The photo itself is low quality, zoomed in with digital artefacts so we can read the feeling of the scene but no detail. But that is fine, and the point. These are snapshots of awareness, not composed masterpieces – though for all we know they may eventually feed into a chapter’s moment, an artistic project, or a song lyric.

Figs.v,vi

The book departs the public to also enter the private domain of creativity. A top-down image from William Kentridge – subtitled with his quote “silence reigns supreme” – shows his working station, charcoal, ink, paper, and sketchbooks scattered across a desk. It’s partly performative, as all photography is at its heart, but also insight into process. A dirtier detail is presented by Jeff Wall via Dexter Dalwood. Wall’s Diagonal Composition (1993) is of the artist’s studio, carefully composed before being presented in a lightbox image shown at Tate Modern in London, presumably where Dalwood photographed it himself.

On the facing page of the spread is a contribution from singer Jarvis Cocker. As with Dalwood it is a rephotograph of another creative’s work and space, as the Pulp singer’s comment under the image reads: “Just been tidying my room … Only joking: this is an artwork called La Piece de Vie by Robert Combas. It features in an exhibition by the author Michel Houellebecq.”

In this image we see how the creative mind reads spaces and images. They collect, but credit, observe a history and provenance, but rearticulate it for a new idea. This is how photographic mediation works, and how Instagram has perpetuated its shareability and replicability. Seeing Things doesn’t so much critique this mediated power of the image, but offers an analogue continuation of the process.

Figs.vii,viii

Redstone Press is the publisher of surprising books and games. From Soviet graphic arts to psychological tests to their iconic diary with a different theme each year—each subject is explored in an original and imaginative way. The 2023 edition of The Redstone Diary asks the question, "What is beauty?" Philosophers have often asked the question—as have artists, poets, lovers, thinkers, explorers, family, friends. The diary features contributions and excerpts from John Baldessari, W.E.B. Du Bois, Louise Bourgeois, Sonia Delaunay, Gilbert and George, Seamus Heaney, Edvard Munch, Marc Quinn and Oliver Sacks.

www.theredstoneshop.com

purchase

Seeing Things can be purchased from most bookshops or directy from the Redstone Press website:

www.theredstoneshop.com/collections/all-available-products/products/seeing-things

images

fig.i Cover, Seeing Things, by Redstone Press. © Redstone Press.

fig.ii “Richard Wentworth, London, New Oxford Street, 2015”, photograph

©

Richard Wentworth, courtesy Redstone Press.

fig.iii “Aristo traditions”, photograph © Carey Young, courtesy Redstone Press.

fig.iv Photograph © Cornelia Parker, courtesy Redstone Press.

fig.v “I see this wonderful lady every day. She feeds the birds. Today, she and the cat were among the pigeons, and I just caught it.”, photograph © Andrew O’Hagen, courtesy Redstone Press.

fig.vi “Jeff Wall, Diagonal composition, 1993”, transparency in lightbox, 40.0 x 46.0 cm. P

hotograph © Dexter Dalwood, courtesy the artist & Redstone Press.

fig.vii “Silence reigns supreme”, photograph of William Kentridge,

© Damon Garstang, courtesy William Kentridge & Redstone Press.

fig.viii “Just been

tidying my room … Only joking: this is an artwork called La Piece de Vie by

Robert Combas. It features in an exhibition by the author Michel Houellebecq.”

photograph © Carey Young, courtesy Redstone Press.

publication date

11 September 2022

tags

Book, Roz Chast, Jarvis Cocker, Robert Combas, Creativity, Instagram,

Looking, Andrew O'Hagen, William Kentridge, Cornelia Parker, Photography, Pigeons,

Process, Redstone Press, Carey Young, Jeff Wall, Richard Wentworth

www.theredstoneshop.com/collections/all-available-products/products/seeing-things