Carey Young: making space

In her largest institutional show in the UK, artist Carey

Young presents a mix of moving & still image works from two decades of

making. At Modern Art Oxford, works across a variety of approaches and mediums consider

issues of space, power, the body, and legal superstructures which tie all these

together, as explored by Will Jennings.

It is now possible for Brits to re-join the European Union.

Briefly. And somewhat physically restrained. But, nonetheless, there is a

momentary legal loophole in Oxford by which you, personally, become a temporary

citizen of the EU. Whether this would stand up in court remains to be tested, but

for the creator of this alternate reality, artist Carey Young, it is resolutely

real. “Political borders are a legal fiction we happen to have agreed on,” she

explains.

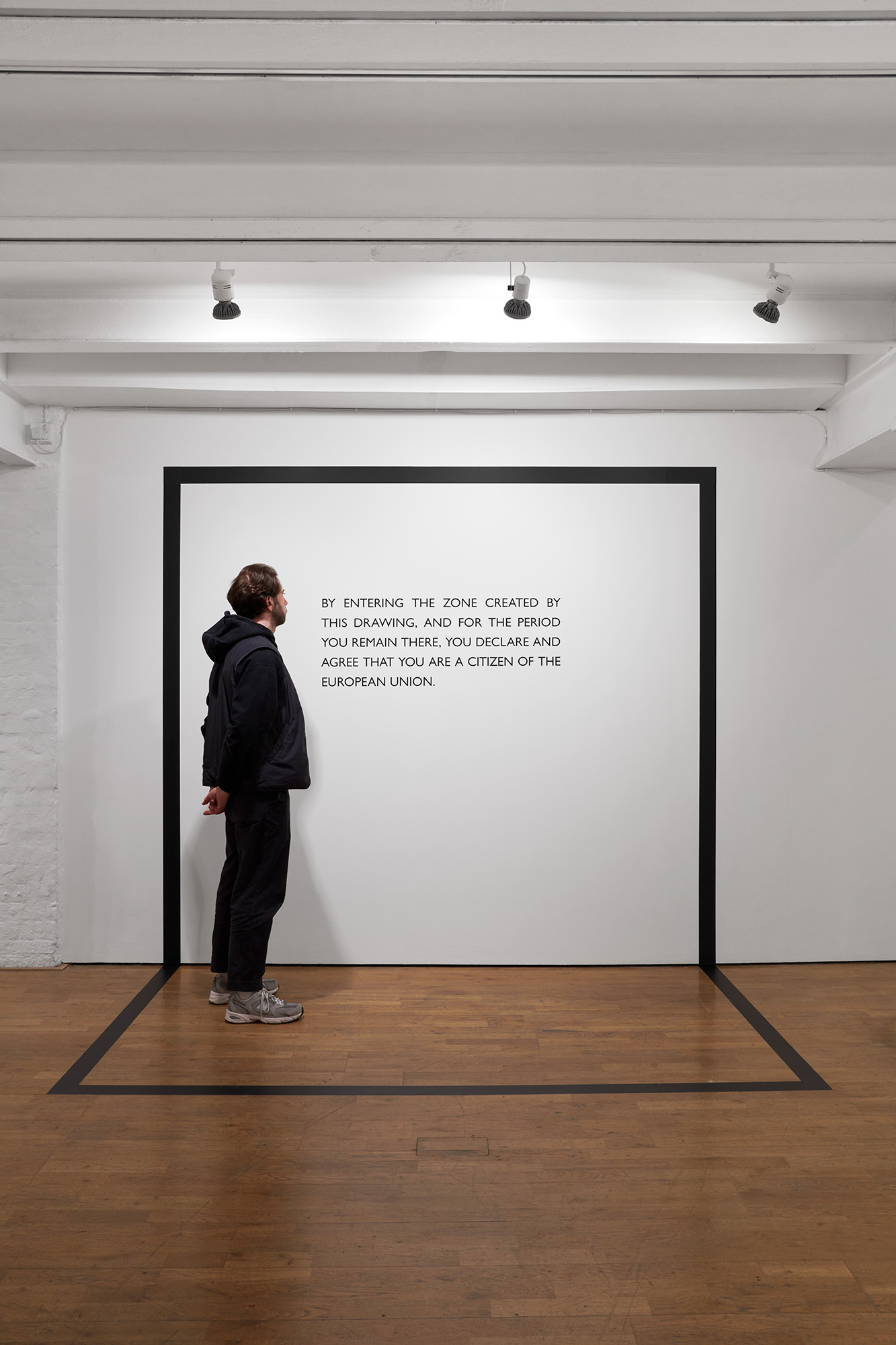

In her solo exhibition in Modern Art Oxford, there is a thick, single black line drawn onto the newly whitewashed walls and polished floor. It forms a rectangle across both surfaces, and invites the visitors to cross into its imagined space with the words: BY ENTERING THE ZONE CREATED BY THIS DRAWING, AND FOR THE PERIOD YOU REMAIN THERE, YOU DECLARE AND AGREE THAT YOU ARE A CITIZEN OF THE EUROPEAN UNION

![]()

The work is Declared Void III (2013/2023). “It is a real contract: I am making an offer and the viewer accepts it by crossing the line, and by doing that they enter my hallucination,” Young explains, and her work is intrinsically interested in this imaginary but enforced structure which surrounds everything we do and everyone we are. Of course, law is equal – anybody can enter Young’s provocative EU space – but we well know that the application of law is far from equal. Legal systems and are wrapped by a more powerful one containing patriarchy, imperialism, racism, and other superstructures that all too often seem to impact or affect the logical legal frameworks underneath.

The centrepiece of this exhibition is Appearance (2023), a video work drawing from Andy Warhol’s screentest series – in which a celebrated protagonist sat in front of a camera, motionless as if a photo for a period – to focus on female judges working within the UK legal system. The judge is a position of power, who can adjudicate on situation and individual, and within a superstructure of patriarchy Young is both celebrating that women of various backgrounds have broken the glass ceiling to take such a position, but also exploring their modes of presence and identity within a role which comes with specific clothes, sensibilities, and gravitas, all born from another age and a male-centred world.

![]()

![]()

Figs.ii,iii

These are judges including Dame Bobbie Cheema-Grubb, the

first Asian woman appointed as a High Court Judge. Or Her Honour Judge Barbara

Mensah, the first UK Circuit Judge of African Origin when appointed as late as

2005, also the first university graduate from her family. Or Master Victoria

McCloud, the youngest person to hold the position of Master category or judge,

and also the first trans person to practise as a barrister then as a judge in

2006. Or Deputy District Judge Raffia Arshad, who in 2020 was appointed as one

of the first hijab wearing judges.

The hijab is important. Dress and artifice is one of the superstructures which we use to both create our position in the world, but also one from which others take assumption and presumption. That judges wear wigs is already a patriarchal logic – men have short hair, ready for the legal garnish to sit atop. Young’s screentests deal with these supplanted layers of femininity, race, gender and so on not through heavy-handedness, but simply observing the person be themselves, in both space but also the structural accoutrements of the trade. This is a work about power and how it is afforded and worn, but the power here – as it was in Warhol’s screentests – is not just in the sitter and their presence or sense of self, but also that of the camera and its own agency of control.

![]()

![]()

![]()

“I’m interested in judges, and law in particular, because we are citizens, but we are also legal subjects,” Young says, but in her gaze the judges are not only arbitrators of subjects, but the subject themself of her durational looking. In another recent film, The Vision Machine (2020), Young visited SIGMA’s Japanese factory, where the lenses for photographic and cinematic cameras are built. Across scenes that have a somewhat Kubrickian space-age quality to them – due to the immaculate, dust-free, white spaces and workwear required to create such delicate technology – Young’s camera solely concentrates upon female workers attentively and meticulously cleaning and inspecting lenses.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Having studied fine art photography, since 2013 Young has also held an Honorary Fellowship in the School of Law, Birkbeck, University of London. Increasingly, her practice lies in film-making, but legal situations and how the body finds its place in space is central across her two decades of making, with a variety of works across photography and installation included in the Oxford exhibition alongside moving image. As with the declared void, Obsidian Contract (2010) invites the viewer into a spatial, legal contract. Reverse text in vinyl is presented on the wall, only legible when reading it in a black mirror facing it across the corner of the wall.

On inspection, we learn that by reading the mirrored text for longer than ten seconds we agree that all space we can see in the reflected view is declared common land. As soon we look away, the legal contract ends, the piece wrapped up with a black glass aesthetic conjuring memories of volcanic glass spirit mirrors, such as that owned by occultist John Dee to summon visions of angels. Here, the distant apparition is one of equality and shared ownership, but not an historical romance, Young stating that “common rights go up to the modern day, photography is banned as places are privatised.”

![]()

The third film on display pulls together many of Young’s concerns. Palais de Justice (2017) is a meditative study of the Belgian national lawcourts, and the females who occupy its echoing, cavernous spaces. “It’s a working courthouse, but parts of it are collapsing,” Young says of the building designed by Joseph Poelaert and completed in 1883. Already poetically considered by WG Sebald in his novel Austerlitz, the protagonist wandering “for hours through this mountain range of stone, through forests of columns, past colossal statues, upstairs and downstairs, and no one ever asked him what he wanted.”

Just as the character had, Young also meandered and observed the labyrinthine building anonymously. Having had repeated requests for access to film rejected, she carried on guerrilla-style: dressing down and like a tourist, carrying a rucksack and not a photographer’s kit bag, and not looking through the camera while filming. Also, she adds, “I recommend being a woman, nobody takes you seriously.”

![]()

![]()

The women subject to her camera’s gaze, however, are serious and important. There are judges, observed through circular windows in doors to the courtrooms, acting like lenses, through which we see judges looking back – aware of being filmed as the screentest sitters, but in a tacit, silent agreement. Other women occupy this most masculine of spaces: cleaners polish the endless surfaces and a student sits on steps to produce a sketch of the building. Both serious, both important.

The central conceits of gender, power, legality, and architecture all play across Young’s moving and still image works. There’s a dry humour present, albeit rooted in seriousness and often dry legalese, but these are the components of what it is to position one’s body within highly politicised landscapes and spaces of capitalism – especially for those who have for centuries been built out of those very spaces or whose presence has been invisibilised. The camera, so often a tool of control, surveillance, and archiving, is here used as a tool of escape and awareness, allowing consensual focus in place of an historic male gaze.

Architecture is more than scenography. Through Young’s eye, it is also protagonist, ripe for being reseen and reshaped. This is true of the oppressively solid voids of the Palais de Justice, softened through simple feminine existence and work poetically observed, patiently and slowly.

It is also true in the installations, which reconsider our understanding of space. The urbanist Edward Soja conceives of three types of space: Firstspace, the physical realm as a product of planning, politics, and design; Secondspace, the psychological and conceptual reading of the physical realm within the minds of those who occupy it; and Thirdspace, the combination of the two former spaces of potential, imagination, and socially lived existences. For Young, the Firstspace is a tool for creative and critical consideration, her works inviting reconfiguration of Secondspace and our assumptions and expectations of it, rooted in law, system, and politics. The result, a poetic and provocative Thirdspace which invites shifts in our gaze and imagination, and pushes for a new sense of spatial embodiment.

![]()

In her solo exhibition in Modern Art Oxford, there is a thick, single black line drawn onto the newly whitewashed walls and polished floor. It forms a rectangle across both surfaces, and invites the visitors to cross into its imagined space with the words: BY ENTERING THE ZONE CREATED BY THIS DRAWING, AND FOR THE PERIOD YOU REMAIN THERE, YOU DECLARE AND AGREE THAT YOU ARE A CITIZEN OF THE EUROPEAN UNION

Fig.i

The work is Declared Void III (2013/2023). “It is a real contract: I am making an offer and the viewer accepts it by crossing the line, and by doing that they enter my hallucination,” Young explains, and her work is intrinsically interested in this imaginary but enforced structure which surrounds everything we do and everyone we are. Of course, law is equal – anybody can enter Young’s provocative EU space – but we well know that the application of law is far from equal. Legal systems and are wrapped by a more powerful one containing patriarchy, imperialism, racism, and other superstructures that all too often seem to impact or affect the logical legal frameworks underneath.

The centrepiece of this exhibition is Appearance (2023), a video work drawing from Andy Warhol’s screentest series – in which a celebrated protagonist sat in front of a camera, motionless as if a photo for a period – to focus on female judges working within the UK legal system. The judge is a position of power, who can adjudicate on situation and individual, and within a superstructure of patriarchy Young is both celebrating that women of various backgrounds have broken the glass ceiling to take such a position, but also exploring their modes of presence and identity within a role which comes with specific clothes, sensibilities, and gravitas, all born from another age and a male-centred world.

Figs.ii,iii

The hijab is important. Dress and artifice is one of the superstructures which we use to both create our position in the world, but also one from which others take assumption and presumption. That judges wear wigs is already a patriarchal logic – men have short hair, ready for the legal garnish to sit atop. Young’s screentests deal with these supplanted layers of femininity, race, gender and so on not through heavy-handedness, but simply observing the person be themselves, in both space but also the structural accoutrements of the trade. This is a work about power and how it is afforded and worn, but the power here – as it was in Warhol’s screentests – is not just in the sitter and their presence or sense of self, but also that of the camera and its own agency of control.

Figs.iv-vi

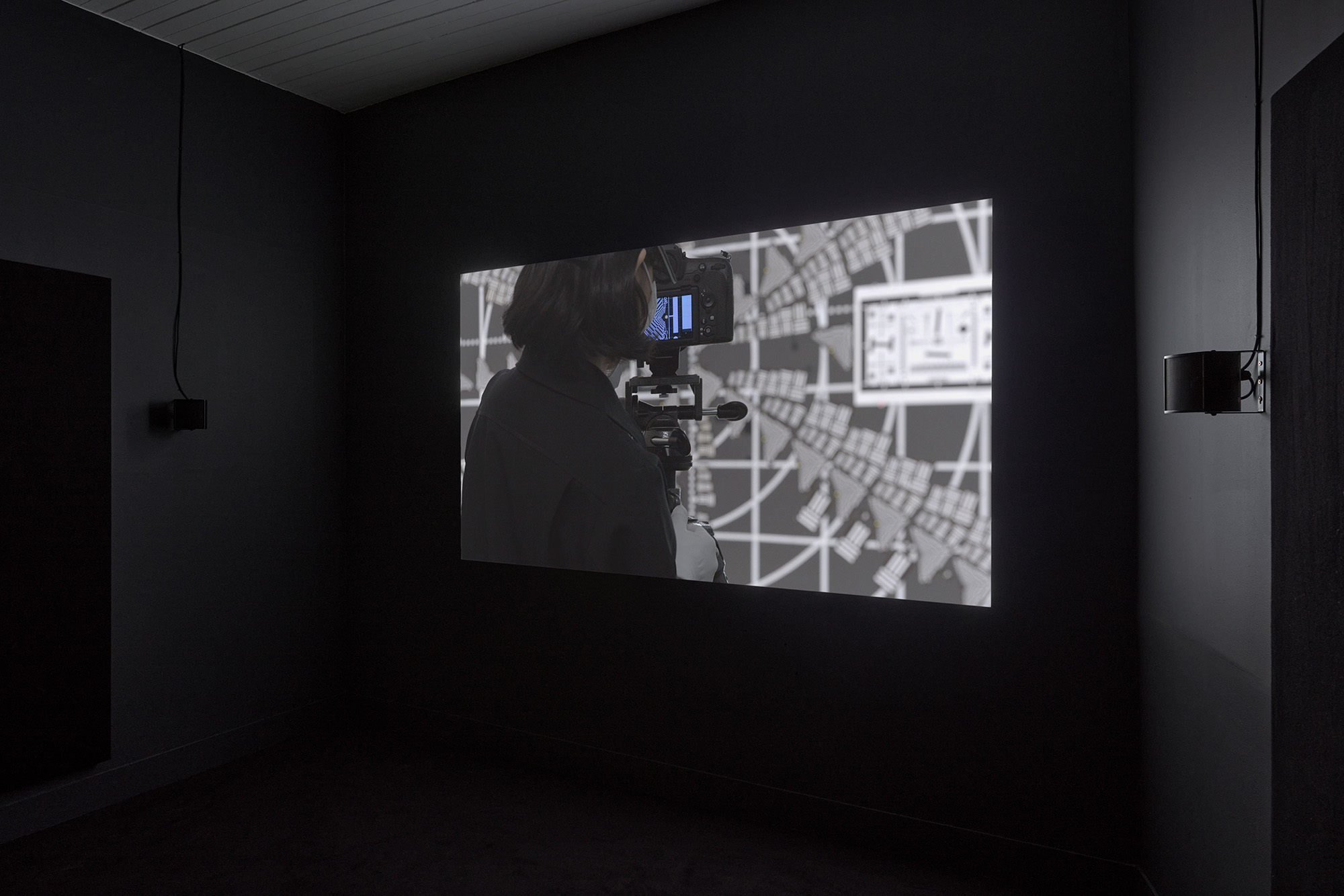

“I’m interested in judges, and law in particular, because we are citizens, but we are also legal subjects,” Young says, but in her gaze the judges are not only arbitrators of subjects, but the subject themself of her durational looking. In another recent film, The Vision Machine (2020), Young visited SIGMA’s Japanese factory, where the lenses for photographic and cinematic cameras are built. Across scenes that have a somewhat Kubrickian space-age quality to them – due to the immaculate, dust-free, white spaces and workwear required to create such delicate technology – Young’s camera solely concentrates upon female workers attentively and meticulously cleaning and inspecting lenses.

Figs.vii-ix

Having studied fine art photography, since 2013 Young has also held an Honorary Fellowship in the School of Law, Birkbeck, University of London. Increasingly, her practice lies in film-making, but legal situations and how the body finds its place in space is central across her two decades of making, with a variety of works across photography and installation included in the Oxford exhibition alongside moving image. As with the declared void, Obsidian Contract (2010) invites the viewer into a spatial, legal contract. Reverse text in vinyl is presented on the wall, only legible when reading it in a black mirror facing it across the corner of the wall.

On inspection, we learn that by reading the mirrored text for longer than ten seconds we agree that all space we can see in the reflected view is declared common land. As soon we look away, the legal contract ends, the piece wrapped up with a black glass aesthetic conjuring memories of volcanic glass spirit mirrors, such as that owned by occultist John Dee to summon visions of angels. Here, the distant apparition is one of equality and shared ownership, but not an historical romance, Young stating that “common rights go up to the modern day, photography is banned as places are privatised.”

Fig.x

The third film on display pulls together many of Young’s concerns. Palais de Justice (2017) is a meditative study of the Belgian national lawcourts, and the females who occupy its echoing, cavernous spaces. “It’s a working courthouse, but parts of it are collapsing,” Young says of the building designed by Joseph Poelaert and completed in 1883. Already poetically considered by WG Sebald in his novel Austerlitz, the protagonist wandering “for hours through this mountain range of stone, through forests of columns, past colossal statues, upstairs and downstairs, and no one ever asked him what he wanted.”

Just as the character had, Young also meandered and observed the labyrinthine building anonymously. Having had repeated requests for access to film rejected, she carried on guerrilla-style: dressing down and like a tourist, carrying a rucksack and not a photographer’s kit bag, and not looking through the camera while filming. Also, she adds, “I recommend being a woman, nobody takes you seriously.”

Figs.xi,xii

The women subject to her camera’s gaze, however, are serious and important. There are judges, observed through circular windows in doors to the courtrooms, acting like lenses, through which we see judges looking back – aware of being filmed as the screentest sitters, but in a tacit, silent agreement. Other women occupy this most masculine of spaces: cleaners polish the endless surfaces and a student sits on steps to produce a sketch of the building. Both serious, both important.

The central conceits of gender, power, legality, and architecture all play across Young’s moving and still image works. There’s a dry humour present, albeit rooted in seriousness and often dry legalese, but these are the components of what it is to position one’s body within highly politicised landscapes and spaces of capitalism – especially for those who have for centuries been built out of those very spaces or whose presence has been invisibilised. The camera, so often a tool of control, surveillance, and archiving, is here used as a tool of escape and awareness, allowing consensual focus in place of an historic male gaze.

Architecture is more than scenography. Through Young’s eye, it is also protagonist, ripe for being reseen and reshaped. This is true of the oppressively solid voids of the Palais de Justice, softened through simple feminine existence and work poetically observed, patiently and slowly.

It is also true in the installations, which reconsider our understanding of space. The urbanist Edward Soja conceives of three types of space: Firstspace, the physical realm as a product of planning, politics, and design; Secondspace, the psychological and conceptual reading of the physical realm within the minds of those who occupy it; and Thirdspace, the combination of the two former spaces of potential, imagination, and socially lived existences. For Young, the Firstspace is a tool for creative and critical consideration, her works inviting reconfiguration of Secondspace and our assumptions and expectations of it, rooted in law, system, and politics. The result, a poetic and provocative Thirdspace which invites shifts in our gaze and imagination, and pushes for a new sense of spatial embodiment.

Fig.xiii

Carey

Young gained an MA in Photography from the Royal College of Art in 1997. Using

video, photography, text, print, performance & installation, her work

explores relations between the body, language, rhetoric & systems of power.

Since 2002, she has developed a large series of works which address &

explore law, which have involved collaborations with lawyers. Young’s work has

been exhibited widely, including solo shows at Kunsthal Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark

(2020), La Loge, Brussels (2019), Towner Art Gallery (2019), Dallas Museum of

Art (2017), Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich (2013), The Power Plant,

Toronto (2009), Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (2009), Eastside Projects

(Birmingham, 2009 & tour) and John Hansard Gallery (Southampton, 2001).

Group shows include Centre Pompidou (Paris and Brussels), New Museum (New

York), Whitechapel Gallery, Tate Britain, Tate Liverpool, ICA (London),

Secession (Vienna) and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, amongst many others.

She has participated in numerous biennials, including Busan (2020), Moscow

(2013, 2007), Taipei (2010), Sharjah (2005), and Venice (2003). She received a

Paul Hamlyn Award for Artists in 2021.

www.careyyoung.com

visit

Carey Young’s exhibition, Appearance, is exhibited at Modern

Art Oxford until 2 July 2023.

Full details available at: www.modernartoxford.org.uk/whats-on/carey-young

images

fig.i Carey Young, Declared Void III (2005-23). Carey Young, Appearance, installation view at Modern Art Oxford, 2023. Photo by Ben Westoby. © Modern Art Oxford

figs.ii,iii Carey Young, Appearance (2023) installation view at Modern Art Oxford, 2023. Photo by Ben Westoby. © Modern Art Oxford

figs.iv-vi

Carey Young, details from Appearance (2023). © Carey Young. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

figx.vii,ix Carey Young, The Vision Machine (2020). installation view at Modern Art Oxford, 2023. Photo by Ben Westoby. © Modern Art Oxford

fig.viii Carey Young, still from The Vision Machine (2020). © Carey Young. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

fig.ix Carey Young, Obsidian Contract (2010). Carey Young, installation view at Modern Art Oxford, 2023. Detail of photo by Ben Westoby. © Modern Art Oxford

figs.xi,xii Carey Young, stills from Palais de Justice (2017). © Carey Young. Courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

fig.xiii Carey Young, Declared Void III (2005-23). Carey Young, installation view at Modern Art Oxford, 2023. Photo by Ben Westoby. © Modern Art Oxford

publication date

30 May 2023

tags

Camera,

Capitalism, Commons, Court, John Dee, Factory, Film, Gender, Judge, Invisible, Will

Jennings, Law, Legal, Lens, Male gaze, Mirror, Modern Art Oxford, Palais de

Justice, Photography, Joseph Poelaert, Politics, Power, Reflection, WG Sebald, Sigma,

Edward Soja, Space, Spatial, Text, Andy Warhol, Women, Carey Young

Full details available at: www.modernartoxford.org.uk/whats-on/carey-young