In bloom: Konstantin Zhukov‘s intimate & ephemeral Black

Carnation

The gay cruising scene of Soviet Riga was not only transposed

into a small London gallery, but also onto an ephemeral material used for the

train tickets gay men used to reach sites of encounter. Will Ferreira Dyke visited

Neven gallery to discover Konstantin Zhukov’s presentation Black Carnation

Part Three, his first exhibition in the UK and one continuing the artist’s

exploration of Latvia’s LGBTQ+ history.

Thursday nights for many in East London – embarrassingly – means

one of both of two things; pricey post-work pints and private views. A few weeks back,

I left the office in search of both and heading down Cambridge Heath Road, found

my way into a cubbyhole of a gallery where twenty minutes previously a friend

had suggested we meet. From the outside, the gallery was unassuming, only made

noticeable by a small wall vinyl which marks the gallery’s name, Neven –

the surname of its eponymous founder, Helen Neven.

The opening that Thursday celebrated Black Carnation Part Three, the debut UK solo exhibition of Latvian artist Konstantin Zhukov, on display for a month and ending on 23 March. As the title implies, this was the third instalment of the artist’s ongoing Black Carnation project, with Zhukov’s exhibition consisted of artworks of contemporary Latvian queer culture, speaking to the nation’s largely absent LGBTQ+ history.

![]()

![]()

Konstantin Zhukov lives and works between Latvia and London, though it is the former, his home country, that he primarily confronts in this project. Following a decade spent in London, where the majority of his experiences as a gay man had taken place, he returned home only to find a “near absence of preserved queer history in Latvia,” stating that “the Soviet period is the biggest blind spot of the 20th century.”

Neither glamourising or idealising the present, nor mourning an unknown past with sorrow and pseudo-nostalgia, the work had a tangible and (dare I say it) zeitgeist-y irreverence. Both the exhibition itself and the exhibited works had a delicate poignancy, one of felt kinship and relational intimacy. Zhukov's work carries the closeness of American photographer Peter Hujar, the sexiness of Robert Mapplethorpe, and Instagram’s censoring of archive Karlheinz Weinberg’s work (see HERE).

His exhibition sought to address this scarcely explored and poorly documented history, with the title Black Carnation derived from a term used to refer to gay men over the 1920 and 1930s, the interwar period of the Latvian Republic before the Soviet occupation and absorption into the USSR. The term was subsequently lost, later rediscovered by the academic Ineta Lipša.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The exhibition itself comprised six framed works, one sculpture, a sound piece, and a window installation. Altering the gallery’s otherwise grey façade, the window collage installation showed interlocking male bodies, captured by Zhukov at a cruising beach a short train ride away from Latvia’s capital, Riga. Where Soho’s Old Compton Street sex shops are decorated by images of oversaturated muscle hunks, Zhukov’s poster boys offer more of a softness, a subtly formed through interlocking and illiterate shapes that welcome you in.

Heading up a staircase one enters the small gallery. Space was tight, yet there was just enough air for each work to have breathing space. Walking around the exhibition it feels as if one was having fleeting intimate interactions with each of the works, as though the gallery visitor was cruising the subjects.

The social and spatial politics of cruising has been explored by numerous scholars, including Jonathan Weinberg, Laud Humphreys, and Alex Espinosza. The subject has also been explored in art, with the topic being tackled by the likes of Leonard Fink, Stanley Stellar, Sunil Gupta, and Alvin Baltrope. In his exploration of the subject, Zhukov considers domestic space, in his notes stating that during the Soviet period, “domestic spaces were often shared, so private space wasn’t actually private and queer people had to look for intimacy outside.” For queers who couldn’t enjoy romantic intimacy in their homes, such fleeting encounters in public space were relied, with the locations becoming a kind of sexual sanctuary.

![]()

![]()

![]()

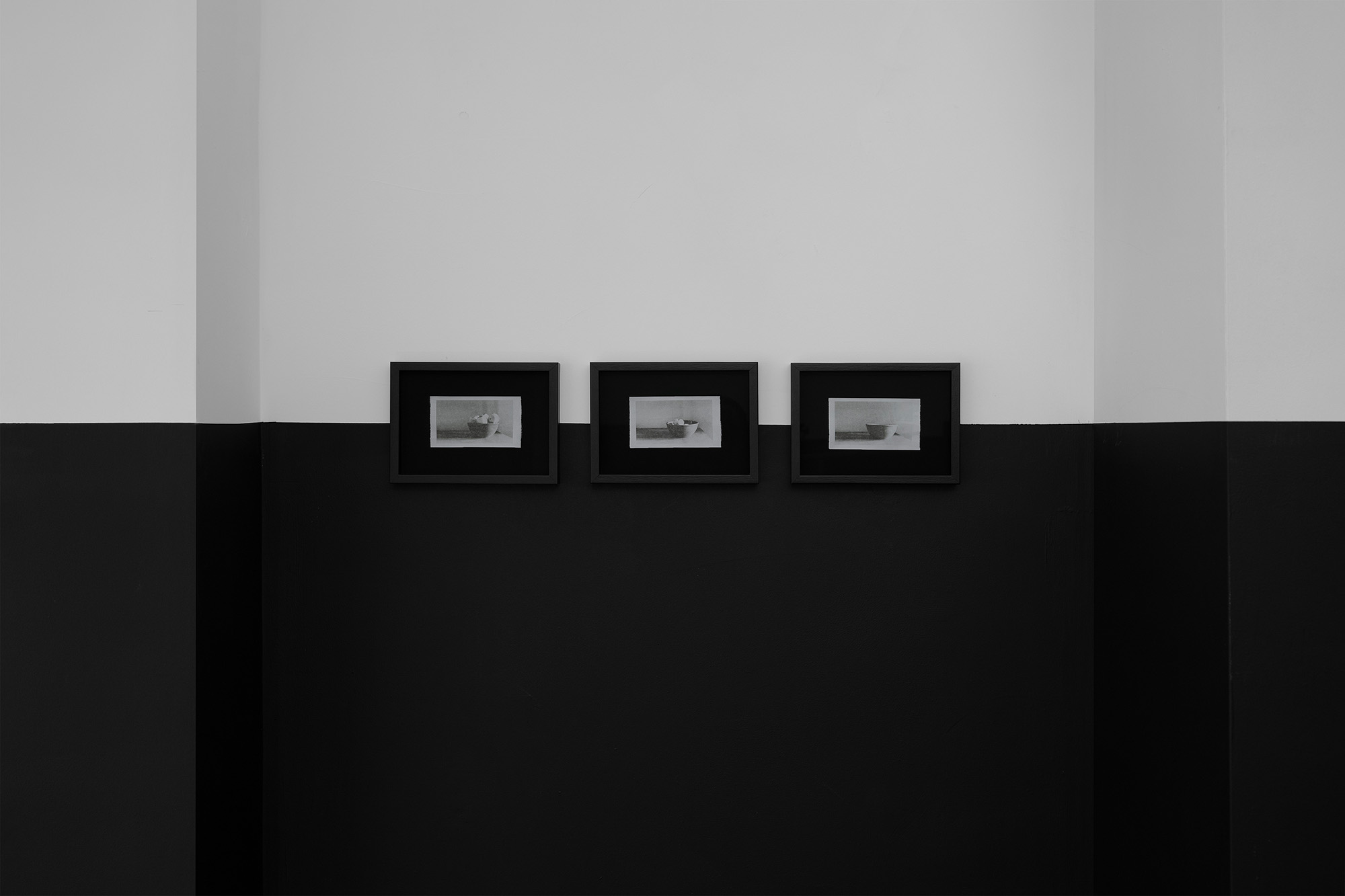

Curatorially, the exhibition was divided on the horizontal by contrasting colours – the upper section painted white, the lower black. Ordinarily this type of curation can feel a little juvenile and obvious, however in this exhibition it worked. This centring line helped to further emphasise the artwork and take over the space, as the frames themselves were moderately small and the sculpture compact, the starkness of the horizontal line contrasting and heightening the delicacy of Zhukov’s work.

Most of the images are of men, though very few seem posed, propped, or choreographed. One image shows a man mid-stretch, another keeps his dignity in a resting contrapposto stance – and the unframed frontal bare cheeks deserve an honorary mention. Within these images is an element of the ordinary and banal, a stillness of the everyday. This is literalised in one of Zhukov’s photographic couplings which pairs human subjects with still life fruit bowls and milk glasses.

The subtlety of these works was deliciously refreshing – so often queer narratives are sensationalised, glamourised, and commercialised to a flatness that denies the breadth of real emotion and feelings. Here, through the quotidian, Zhukov permits for greater dimensionality, the full fat richness of human existence. There is also something to be said about the mundanity of the artist’s materials. Zhukov’s images of unidentifiable men are heat printed onto rolls of the receipt paper used for the train tickets bought for the cruising commute – a productive utilisation of the ephemera and artifacts of the everyday, becoming sensitive and tactile works.

![]()

![]()

This materiality speaks to Latvia’s queer archives and to the “nature of memory itself, a transience, a softness, a fuzzy edginess.” The tangibility of using this receipt paper furthers the intimacy of the images – physically the paper’s frailty is sensed, just as its original purpose is impermanent and disposable. The edges are organically created, and the red warning lines at the end of the till roll underlay the images.

Black Carnation Part Three reminded me of the writing of scholar Jose Esteban Muñoz, who wrote that “ephemerality and its sense of possibility [is] profoundly queer.” Ephemera is innately related to alternative modes of textuality and narrativity, functioning as proof for alternative identities and kinships. The ephemeral does not rest on epistemological foundations, rather it is positioned as traces, glimmers, and residues, purposefully hidden to protect the status of the marginalised subjects it reveals.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Muñoz’s understanding is predicated on Raymond Williams’ notion of the “structure of feeling.” Here “true social content” persists, within elements of social and material experience, beneath, behind, or beyond phenomenal appearance. This feeling of a true queer presence is detectable in Zhukov’s images – whether in the white of the socks worn by the otherwise nude muse, in the glimmer of light reflected off the train doors, or in the subtle ringlet of Zhukov’s subjects hair.

Muñoz suggests that minoritarian subjects do not have any primary or a priori relation to ephemera, memory, or the anecdotal. Rather, he posits that the use of ephemera is a “call attention to the efficacy and, indeed, necessity of such strategies of self-enactment” for queer subjectivities. Zhukov’s works almost directly as Muñoz describes, with ephemera functioning as evidence of Latvia’s unrecorded queer culture and as a necessary call to action for contemporary reflection.

![]()

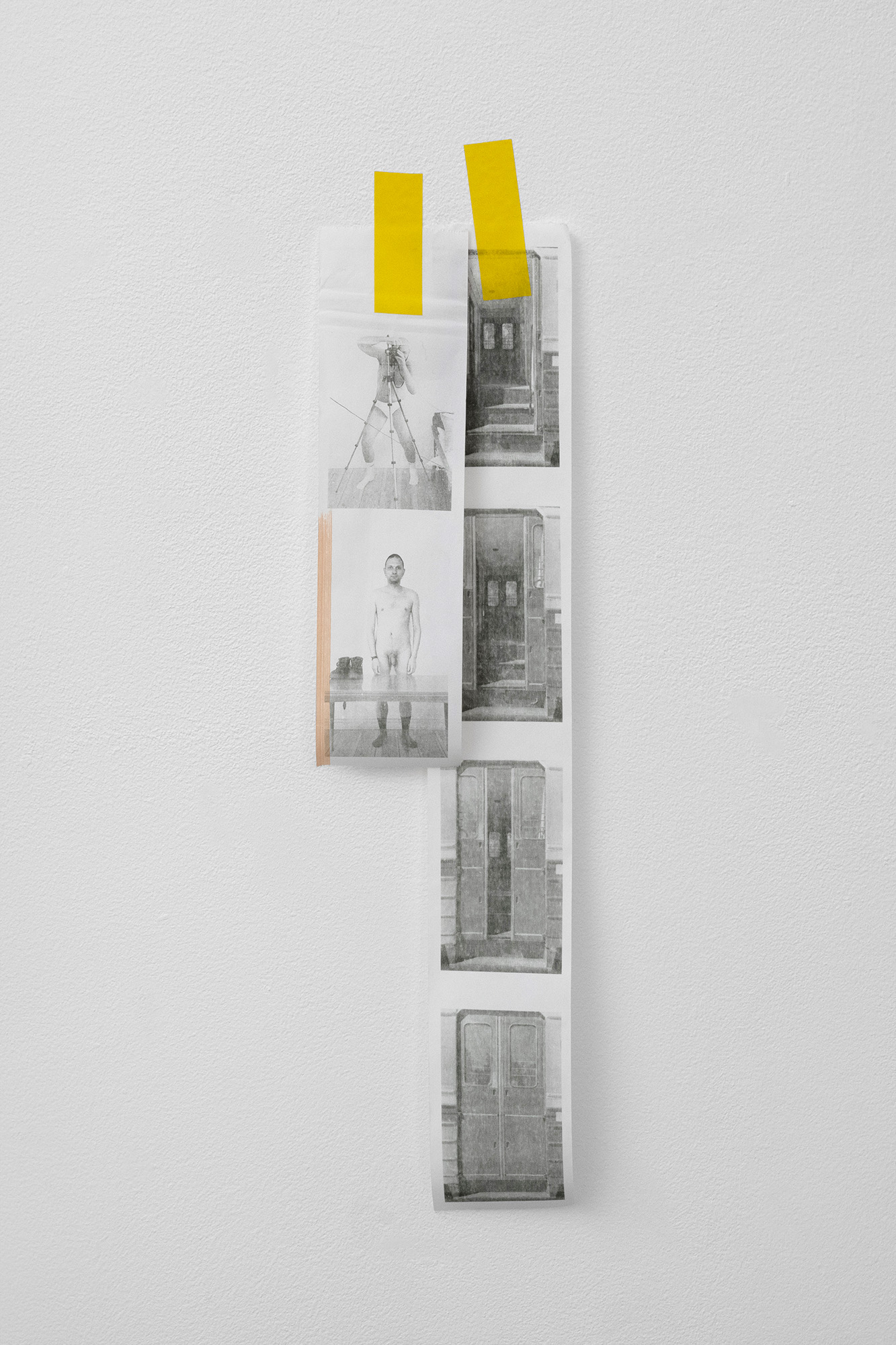

fig.xv

As I left the gallery, and headed swiftly to a gentrified pub, I noticed two unframed printed receipts which I had missed on entry. One of the receipt strips was marked by four faded photographs of the train doors and the other had two figurative depictions; an image of one of Zhukov’s nude subjects and an image of the artist positioned behind a camera wearing white briefs and socks. Hazy and ill-defined these images emitted a warmth and evoked a felt intimacy. The simplicity of these six images summarised the premise of the entire exhibition, functioning as both the perfect terminus, and introductory work.

Whilst the exhibition at Neven has since wilted away and Zhukov’s Black Carnation has come to an end, the importance of archiving queer livelihoods and researching hidden histories continues to bloom. Intimate and ephemeral, Zhukov’s exhibition – despite the fleeting display of subject and setting at Neven – remains evergreen.

The opening that Thursday celebrated Black Carnation Part Three, the debut UK solo exhibition of Latvian artist Konstantin Zhukov, on display for a month and ending on 23 March. As the title implies, this was the third instalment of the artist’s ongoing Black Carnation project, with Zhukov’s exhibition consisted of artworks of contemporary Latvian queer culture, speaking to the nation’s largely absent LGBTQ+ history.

figs.i,ii

Konstantin Zhukov lives and works between Latvia and London, though it is the former, his home country, that he primarily confronts in this project. Following a decade spent in London, where the majority of his experiences as a gay man had taken place, he returned home only to find a “near absence of preserved queer history in Latvia,” stating that “the Soviet period is the biggest blind spot of the 20th century.”

Neither glamourising or idealising the present, nor mourning an unknown past with sorrow and pseudo-nostalgia, the work had a tangible and (dare I say it) zeitgeist-y irreverence. Both the exhibition itself and the exhibited works had a delicate poignancy, one of felt kinship and relational intimacy. Zhukov's work carries the closeness of American photographer Peter Hujar, the sexiness of Robert Mapplethorpe, and Instagram’s censoring of archive Karlheinz Weinberg’s work (see HERE).

His exhibition sought to address this scarcely explored and poorly documented history, with the title Black Carnation derived from a term used to refer to gay men over the 1920 and 1930s, the interwar period of the Latvian Republic before the Soviet occupation and absorption into the USSR. The term was subsequently lost, later rediscovered by the academic Ineta Lipša.

figs.iii-v

The exhibition itself comprised six framed works, one sculpture, a sound piece, and a window installation. Altering the gallery’s otherwise grey façade, the window collage installation showed interlocking male bodies, captured by Zhukov at a cruising beach a short train ride away from Latvia’s capital, Riga. Where Soho’s Old Compton Street sex shops are decorated by images of oversaturated muscle hunks, Zhukov’s poster boys offer more of a softness, a subtly formed through interlocking and illiterate shapes that welcome you in.

Heading up a staircase one enters the small gallery. Space was tight, yet there was just enough air for each work to have breathing space. Walking around the exhibition it feels as if one was having fleeting intimate interactions with each of the works, as though the gallery visitor was cruising the subjects.

The social and spatial politics of cruising has been explored by numerous scholars, including Jonathan Weinberg, Laud Humphreys, and Alex Espinosza. The subject has also been explored in art, with the topic being tackled by the likes of Leonard Fink, Stanley Stellar, Sunil Gupta, and Alvin Baltrope. In his exploration of the subject, Zhukov considers domestic space, in his notes stating that during the Soviet period, “domestic spaces were often shared, so private space wasn’t actually private and queer people had to look for intimacy outside.” For queers who couldn’t enjoy romantic intimacy in their homes, such fleeting encounters in public space were relied, with the locations becoming a kind of sexual sanctuary.

figs.vi-viii

Curatorially, the exhibition was divided on the horizontal by contrasting colours – the upper section painted white, the lower black. Ordinarily this type of curation can feel a little juvenile and obvious, however in this exhibition it worked. This centring line helped to further emphasise the artwork and take over the space, as the frames themselves were moderately small and the sculpture compact, the starkness of the horizontal line contrasting and heightening the delicacy of Zhukov’s work.

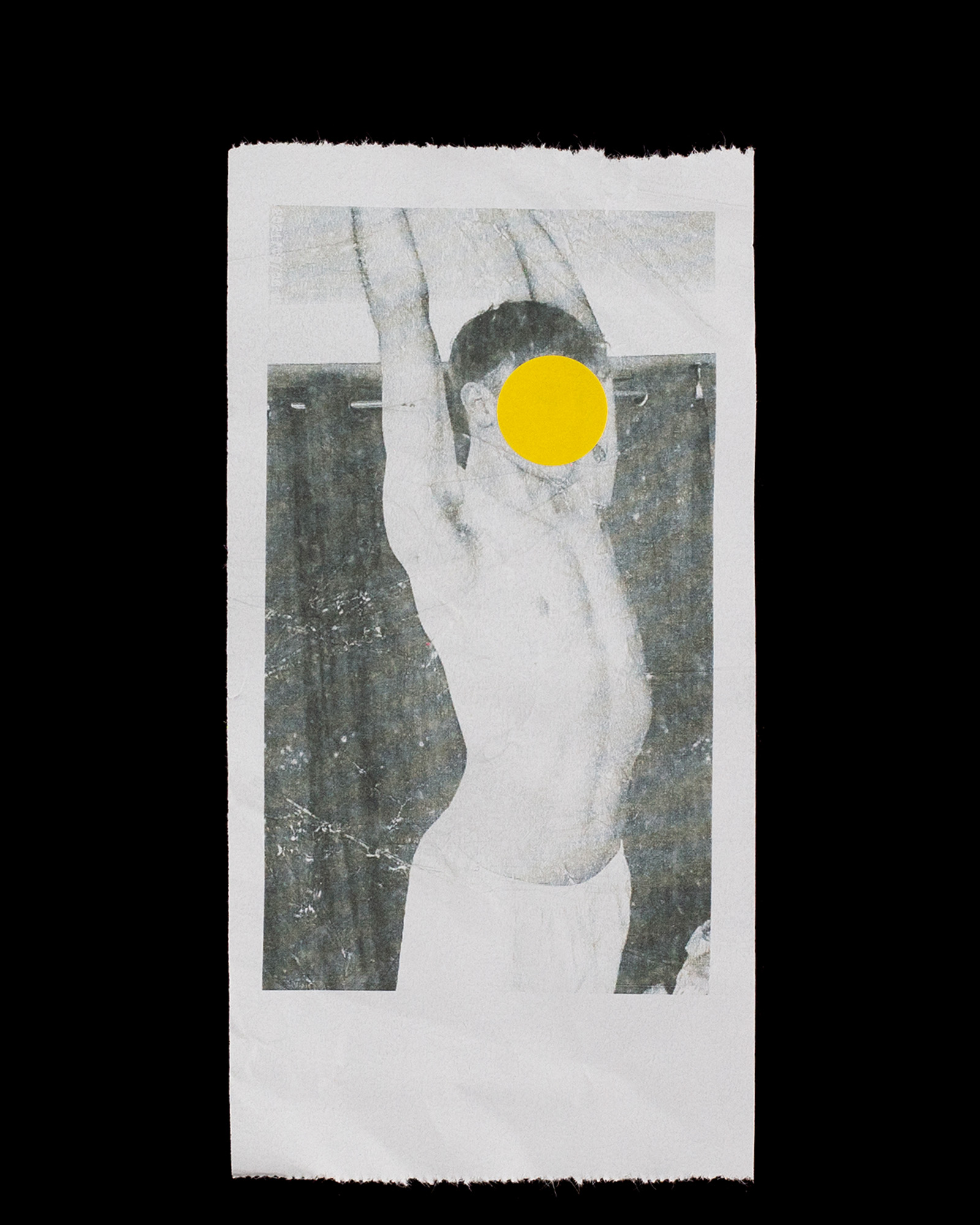

Most of the images are of men, though very few seem posed, propped, or choreographed. One image shows a man mid-stretch, another keeps his dignity in a resting contrapposto stance – and the unframed frontal bare cheeks deserve an honorary mention. Within these images is an element of the ordinary and banal, a stillness of the everyday. This is literalised in one of Zhukov’s photographic couplings which pairs human subjects with still life fruit bowls and milk glasses.

The subtlety of these works was deliciously refreshing – so often queer narratives are sensationalised, glamourised, and commercialised to a flatness that denies the breadth of real emotion and feelings. Here, through the quotidian, Zhukov permits for greater dimensionality, the full fat richness of human existence. There is also something to be said about the mundanity of the artist’s materials. Zhukov’s images of unidentifiable men are heat printed onto rolls of the receipt paper used for the train tickets bought for the cruising commute – a productive utilisation of the ephemera and artifacts of the everyday, becoming sensitive and tactile works.

figs.ix,x

This materiality speaks to Latvia’s queer archives and to the “nature of memory itself, a transience, a softness, a fuzzy edginess.” The tangibility of using this receipt paper furthers the intimacy of the images – physically the paper’s frailty is sensed, just as its original purpose is impermanent and disposable. The edges are organically created, and the red warning lines at the end of the till roll underlay the images.

Black Carnation Part Three reminded me of the writing of scholar Jose Esteban Muñoz, who wrote that “ephemerality and its sense of possibility [is] profoundly queer.” Ephemera is innately related to alternative modes of textuality and narrativity, functioning as proof for alternative identities and kinships. The ephemeral does not rest on epistemological foundations, rather it is positioned as traces, glimmers, and residues, purposefully hidden to protect the status of the marginalised subjects it reveals.

figs.xi-xiv

Muñoz’s understanding is predicated on Raymond Williams’ notion of the “structure of feeling.” Here “true social content” persists, within elements of social and material experience, beneath, behind, or beyond phenomenal appearance. This feeling of a true queer presence is detectable in Zhukov’s images – whether in the white of the socks worn by the otherwise nude muse, in the glimmer of light reflected off the train doors, or in the subtle ringlet of Zhukov’s subjects hair.

Muñoz suggests that minoritarian subjects do not have any primary or a priori relation to ephemera, memory, or the anecdotal. Rather, he posits that the use of ephemera is a “call attention to the efficacy and, indeed, necessity of such strategies of self-enactment” for queer subjectivities. Zhukov’s works almost directly as Muñoz describes, with ephemera functioning as evidence of Latvia’s unrecorded queer culture and as a necessary call to action for contemporary reflection.

fig.xv

As I left the gallery, and headed swiftly to a gentrified pub, I noticed two unframed printed receipts which I had missed on entry. One of the receipt strips was marked by four faded photographs of the train doors and the other had two figurative depictions; an image of one of Zhukov’s nude subjects and an image of the artist positioned behind a camera wearing white briefs and socks. Hazy and ill-defined these images emitted a warmth and evoked a felt intimacy. The simplicity of these six images summarised the premise of the entire exhibition, functioning as both the perfect terminus, and introductory work.

Whilst the exhibition at Neven has since wilted away and Zhukov’s Black Carnation has come to an end, the importance of archiving queer livelihoods and researching hidden histories continues to bloom. Intimate and ephemeral, Zhukov’s exhibition – despite the fleeting display of subject and setting at Neven – remains evergreen.