Models

for a new society: Enzo Mari at the Design Museum

A new exhibition at London’s Design Museum presents over 300

designs & drawings from the life of Enzo Mari, a communist Italian designer

who infused all he created with inventiveness, intelligence, politics & wit.

The exhibition co-curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist & Francesca Giacomelli

richly explores the designer’s life and work across graphics, furniture, toys

& everything between.

“I want to create models for a different society – for a way

of producing and living differently.”

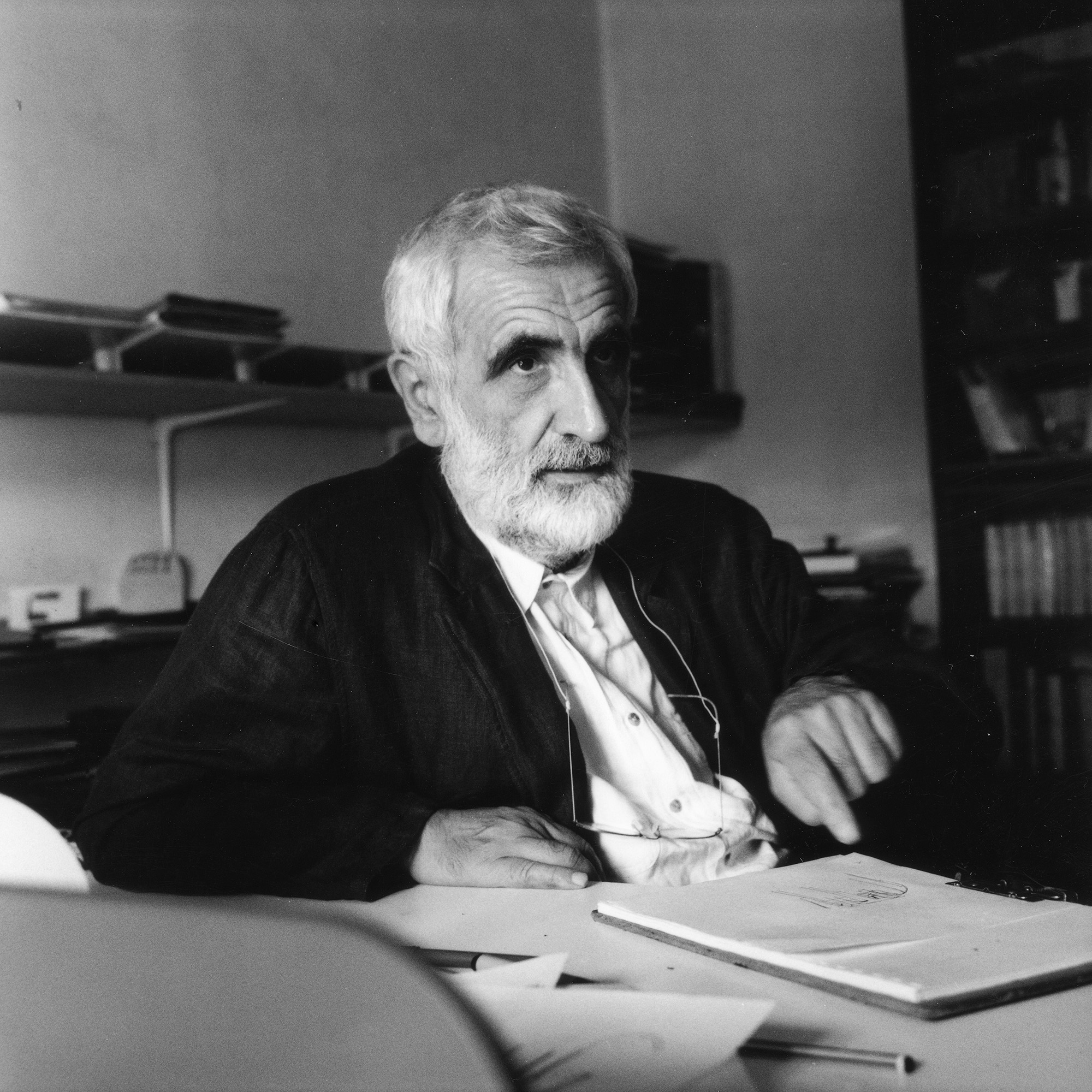

So reads a vinyl quote affixed to a wall near the entrance of Enzo Mari, an exhibition dedicated to the interdisciplinary Italian designer at London’s Design Museum. It’s a quote that goes straight to the heart of a creative you may not have heard of, but who has influenced countless designers who have created objects and graphics you may use daily.

Born in Novara, Italy, in 1932 Mari moved to Milan as a child, a city that would remain his home through to his passing in 2020. It proved a fertile region for his practice, combining a rich mix of business, industrialists, entrepreneurs, and a long history of design across all the disciplines. It was also a city undergoing post-war reinvention, with Mari’s inquisitive, playful, and inventive mind suitably located within a place and people searching for new ways of making and being.

Mari didn’t design architecture, but it is present throughout his practice. The exhibition opens with a look at his work at Milan’s Brera Academy of Fine Art, an institute the working class Mari could attend with no prior qualifications. A tempera on paper collage titled La cittá giardino (The garden city) from 1954 shows an early and literal interest in urbanity and architecture, a grid of repeating axonometric modernist apartment blocks fills a frame uniformly. But architecture is more present more obliquely through tests and models for structures, gridded arrangements, spatial experimentation, and form finding at a small scale but which could easily blow up to room-, building-, or city-scale.

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.i-iii

Over the 1960s, Mari applied some of these form-finding explorations into physical experiences through the design of display spaces for an emerging market of Italian product design. Again, this varied in scale from simple shelving and presentation units formed of simple materials, through to room-filling spectacles to wow the consumer. However, though Mari was wrapped up in the booming consumerist world, the designer was dedicated to a simplicity, affordability, honesty of material, and ethics that meant his ideas and ambition didn’t get sucked into exuberant show and stayed rooted to his communist politics.

Using durable and reparable materials, Mari was interested in ways of empowering the user in the creation and daily use of his designs. Flatpack furniture that the everyman could put together, thus embedding within the object a sense of its construction and quality, is shown at the Design Museum, as well as furniture that can change function and form simply, futureproofing it from commonplace obsolescence. A light system design for Artemide was self-constructed and could be configured into numerous forms. With a simple switch, a sofa with backrest could turn into a bed. A wooden frame system could create any kind of furniture desired, simple forms showing their engineering and structure.

![]()

![]()

![]()

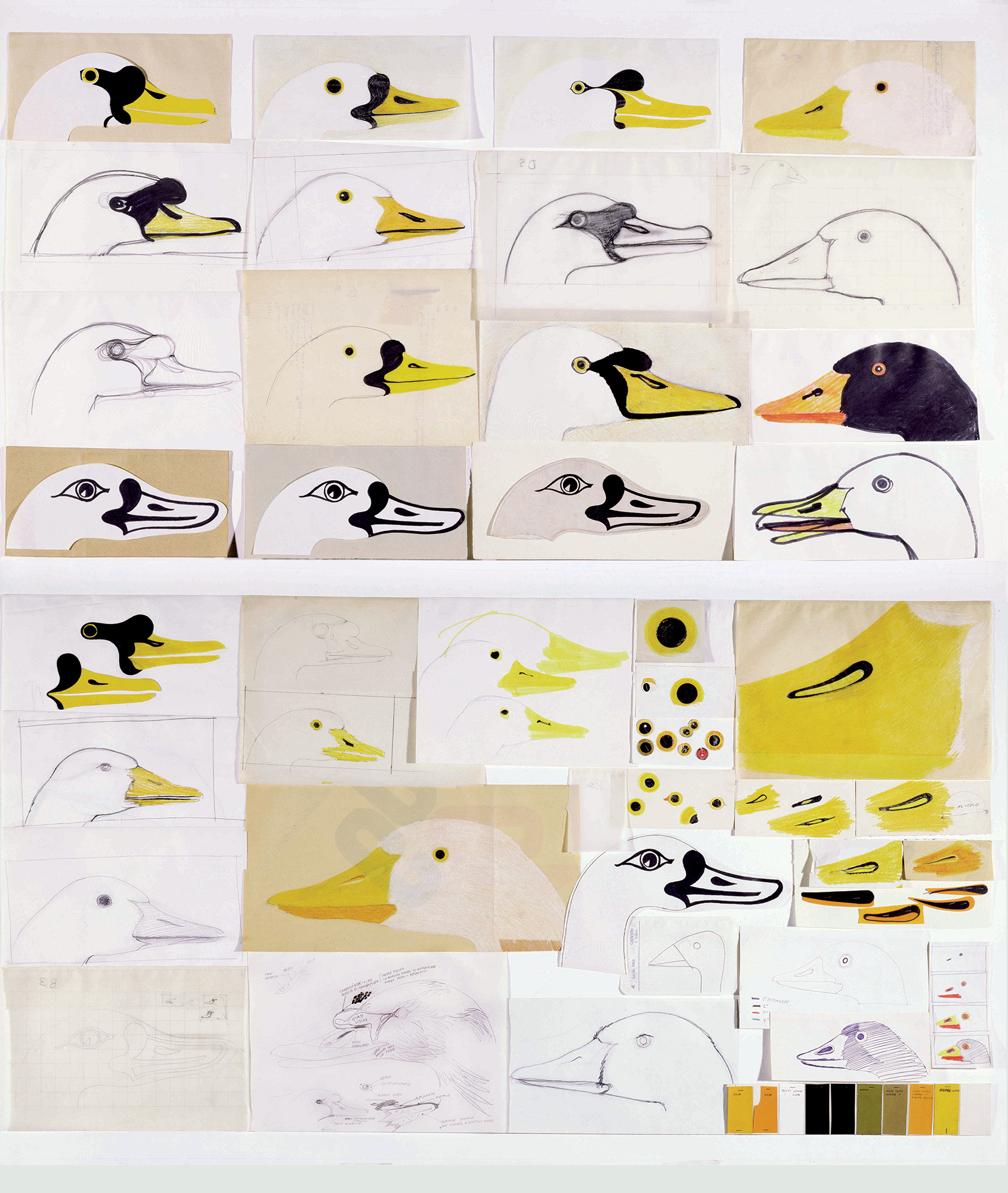

Also central to his philosophy was the notion of play. There is a humour within many of the 300+ objects on display in the exhibition – a wall of sketches shows the development of Mari’s drawing of a goose, pomo-influenced vases are formed to look like cut columns, and throughout often serious and ambitious projects there is a delicate wit. But it is most present within his work for children, an audience for whom Mari designed toys, books, and games at all scales.

Early in his career, Mari became a father, and enjoyed learning from children as they in turn learned from him and the world. Suggesting that children should be awarded to two-year-olds for the speed at which they absorb and respond to new knowledge of the world around them, his philosophical interests led to a hope that by nurturing the creative possibilities in children they would become imbued with the skills, interests, and potential to go on to build a better society as adults.

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.vii-ix

The exhibition is co-curated by Francesca Giacomelli, Mari’s studio project assistant, designer, curator and researcher, and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist who had worked with Mari on a series of interviews and dialogues since the 1990s. Originally presented at the Triennale Milano in 2020 – very shortly before Mari’s death – the Design Museum version expands upon the initial version and is a dense exhibition, requiring a fair amount of time and dedication from the visitor. The rich diversity between Mari’s creations and approaches could lead to a curation that confuses, but by the end of the presentation it is less a single design trajectory that is imparted than a worldview and deeply held care for design across all its disciplines.

This is a care not only about the finished product and user, but also in the creation and working situation of those who worked in factories making the pieces. Mari felt that the skill and labour of workers who physically made his designs should be valued as equally as any designer – a series of drawings from 1974 playfully present maps and diagrams of class division, examining the alienation of labour and production within a capitalist system.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In an exhibition that spans so many ideological, political, and aesthetic ideas, we perhaps learn most about the man Mari in a few smaller-scale vitrines towards the end of the show. A 1998 table with miniature zen-garden contains carefully raked sand with postcards and images of the designer’s most important touchstones where the Japanese garden would have rocks. A 2002 Altare della memoria (Altar of Memory) is a simple surface of staggered metal plains within which photos can be wedged, though here there is only one photo – Mari with a young relative. Then a series of vitrines contain various fragments, objects, and sculptural forms as paperweights upon facsimiles of Mari’s sketches, notes, and writings.

It is in these pieces, perhaps, that the close friendships and deep intellectual closeness of Mari and the two curators is most present. But it is also where the visitor returns to the core of Mari’s worldview after a vast exploration of his lifetime of design. A closing punctuation of the personal, simple, human, and curious.

![]()

![]()

![]()

figs.xiii-xv

So reads a vinyl quote affixed to a wall near the entrance of Enzo Mari, an exhibition dedicated to the interdisciplinary Italian designer at London’s Design Museum. It’s a quote that goes straight to the heart of a creative you may not have heard of, but who has influenced countless designers who have created objects and graphics you may use daily.

Born in Novara, Italy, in 1932 Mari moved to Milan as a child, a city that would remain his home through to his passing in 2020. It proved a fertile region for his practice, combining a rich mix of business, industrialists, entrepreneurs, and a long history of design across all the disciplines. It was also a city undergoing post-war reinvention, with Mari’s inquisitive, playful, and inventive mind suitably located within a place and people searching for new ways of making and being.

Mari didn’t design architecture, but it is present throughout his practice. The exhibition opens with a look at his work at Milan’s Brera Academy of Fine Art, an institute the working class Mari could attend with no prior qualifications. A tempera on paper collage titled La cittá giardino (The garden city) from 1954 shows an early and literal interest in urbanity and architecture, a grid of repeating axonometric modernist apartment blocks fills a frame uniformly. But architecture is more present more obliquely through tests and models for structures, gridded arrangements, spatial experimentation, and form finding at a small scale but which could easily blow up to room-, building-, or city-scale.

figs.i-iii

Over the 1960s, Mari applied some of these form-finding explorations into physical experiences through the design of display spaces for an emerging market of Italian product design. Again, this varied in scale from simple shelving and presentation units formed of simple materials, through to room-filling spectacles to wow the consumer. However, though Mari was wrapped up in the booming consumerist world, the designer was dedicated to a simplicity, affordability, honesty of material, and ethics that meant his ideas and ambition didn’t get sucked into exuberant show and stayed rooted to his communist politics.

Using durable and reparable materials, Mari was interested in ways of empowering the user in the creation and daily use of his designs. Flatpack furniture that the everyman could put together, thus embedding within the object a sense of its construction and quality, is shown at the Design Museum, as well as furniture that can change function and form simply, futureproofing it from commonplace obsolescence. A light system design for Artemide was self-constructed and could be configured into numerous forms. With a simple switch, a sofa with backrest could turn into a bed. A wooden frame system could create any kind of furniture desired, simple forms showing their engineering and structure.

figs.iv-vi

Also central to his philosophy was the notion of play. There is a humour within many of the 300+ objects on display in the exhibition – a wall of sketches shows the development of Mari’s drawing of a goose, pomo-influenced vases are formed to look like cut columns, and throughout often serious and ambitious projects there is a delicate wit. But it is most present within his work for children, an audience for whom Mari designed toys, books, and games at all scales.

Early in his career, Mari became a father, and enjoyed learning from children as they in turn learned from him and the world. Suggesting that children should be awarded to two-year-olds for the speed at which they absorb and respond to new knowledge of the world around them, his philosophical interests led to a hope that by nurturing the creative possibilities in children they would become imbued with the skills, interests, and potential to go on to build a better society as adults.

figs.vii-ix

The exhibition is co-curated by Francesca Giacomelli, Mari’s studio project assistant, designer, curator and researcher, and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist who had worked with Mari on a series of interviews and dialogues since the 1990s. Originally presented at the Triennale Milano in 2020 – very shortly before Mari’s death – the Design Museum version expands upon the initial version and is a dense exhibition, requiring a fair amount of time and dedication from the visitor. The rich diversity between Mari’s creations and approaches could lead to a curation that confuses, but by the end of the presentation it is less a single design trajectory that is imparted than a worldview and deeply held care for design across all its disciplines.

This is a care not only about the finished product and user, but also in the creation and working situation of those who worked in factories making the pieces. Mari felt that the skill and labour of workers who physically made his designs should be valued as equally as any designer – a series of drawings from 1974 playfully present maps and diagrams of class division, examining the alienation of labour and production within a capitalist system.

figs.x-xii

In an exhibition that spans so many ideological, political, and aesthetic ideas, we perhaps learn most about the man Mari in a few smaller-scale vitrines towards the end of the show. A 1998 table with miniature zen-garden contains carefully raked sand with postcards and images of the designer’s most important touchstones where the Japanese garden would have rocks. A 2002 Altare della memoria (Altar of Memory) is a simple surface of staggered metal plains within which photos can be wedged, though here there is only one photo – Mari with a young relative. Then a series of vitrines contain various fragments, objects, and sculptural forms as paperweights upon facsimiles of Mari’s sketches, notes, and writings.

It is in these pieces, perhaps, that the close friendships and deep intellectual closeness of Mari and the two curators is most present. But it is also where the visitor returns to the core of Mari’s worldview after a vast exploration of his lifetime of design. A closing punctuation of the personal, simple, human, and curious.