Life in plastic: the architecture of Barbie

A new exhibition at London’s Design Museum takes into the life of Barbie. It is a world full of fashion, but her passion for design goes deeper with plenty of evidence for the model’s interest in & knowledge of architectural history. The exhibition includes several of her Dreamhouses as well as a lot of her interior design collection, presenting Barbie as an intelligent reader & collector of architecture.

“Life in plastic, it’s fantastic.” So the pop craftsfolk

Aqua sang in their 1997 number one song, Barbie Girl. A new exhibition

at London’s Design Museum tests just that theory with a deep dive into all

things Babie. Amongst the rooms, playfully and colourfully designed by Sam Jacob

Studio architects, there is no shortage of plastic on show, shaped into not

only countless versions of the eponymous woman herself and her erstwhile on/off partner Ken, but also the countless plastic objects she uses to live her life, with

quite a lot of architectural interest.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Barbie was born in 1959 when Ruth Handler of Mattel launched the “teen age fashion model” at New York Toy Fair. The very first Barbie welcomes visitors to the Design Museum show, albeit safely ensconced in a Perspex vitrine, in a black and white stripey number, one of a number of interchangeable outfits made for her. She was homeless until 1962 when her first Dreamhouse was constructed, the first of several abodes that have enabled her to stay at the height of cultural and architectural fashion.

That first Dreamhouse is also presented in the exhibition, in a central room that is a suburban sprawl of former Barbie homes. Her first was made of cardboard, a living space filled with mid-century furniture and the latest technological entertainment – though nowhere to cook. In 1968 she had entered her swinging period (stylistically, that is, Ken has been the main man in her life since 1961) and took ownership of a Family House with moulded furniture, a Carnaby Street sign on the wall, and hand-designed wallpaper with a sixties twist on Edwardian patterns.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Barbie has had quite an eclectic, and knowing, interest in architecture over the years. in 1978 she lived in an A-Frame Dreamhouse which looks not unlike early Frank Gehry modular architecture. By 2021 she had moved into brashly coloured three-storey open-plan update of mid-century modernism, complete with a slide into a pool.

The exhibition has a great number of other houses and interiors – from a 1962 couture showroom to the interior of a lunar space capsule. One section – wonderfully presented as if a street by Sam Jacob Studio, lined up against a golden-hour gradient accessed through an arch – presents a whole series of Barbie’s former homes. There are McMansion qualities to her 1990 Magical Mansion, complete with neoclassical columns and pink rooftiles. She also once owned a two-storey townhouse, a tiny cottage-like Family House with Palladian windows and vines, and a three-floor one-garage Dreamhouse from 2016 offer more nods to her interest in historic architecture through pilasters and pediments.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Elsewhere, we get to explore Barbie’s history of collecting classic design furniture. Chintzy and florally decorated beds, chairs, and tables from the 1980’s interest in traditional interior design can be seen in proximity to her 1998 Trendy Loft fitout, replete with inflatable chair, futon sofa, and lava lamp. There is a collaboration with Kartell with five of the company’s seminal Philippe Starck chairs remade at her scale in a shocking pink.

The exhibition leans heavily upon Mattel’s endorsement and archive – there is little space in the presentation for critique about gender roles, body politics except for how it celebrates the toymaker’s changes and notional progressive changes to their designs and processes. This does mean there are lots of fantastic examples of Barbie and her attachments from across the decades, but the visitor is never allowed to leave the Barbie world created to consider the doll and its roll in society and culture more critically.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

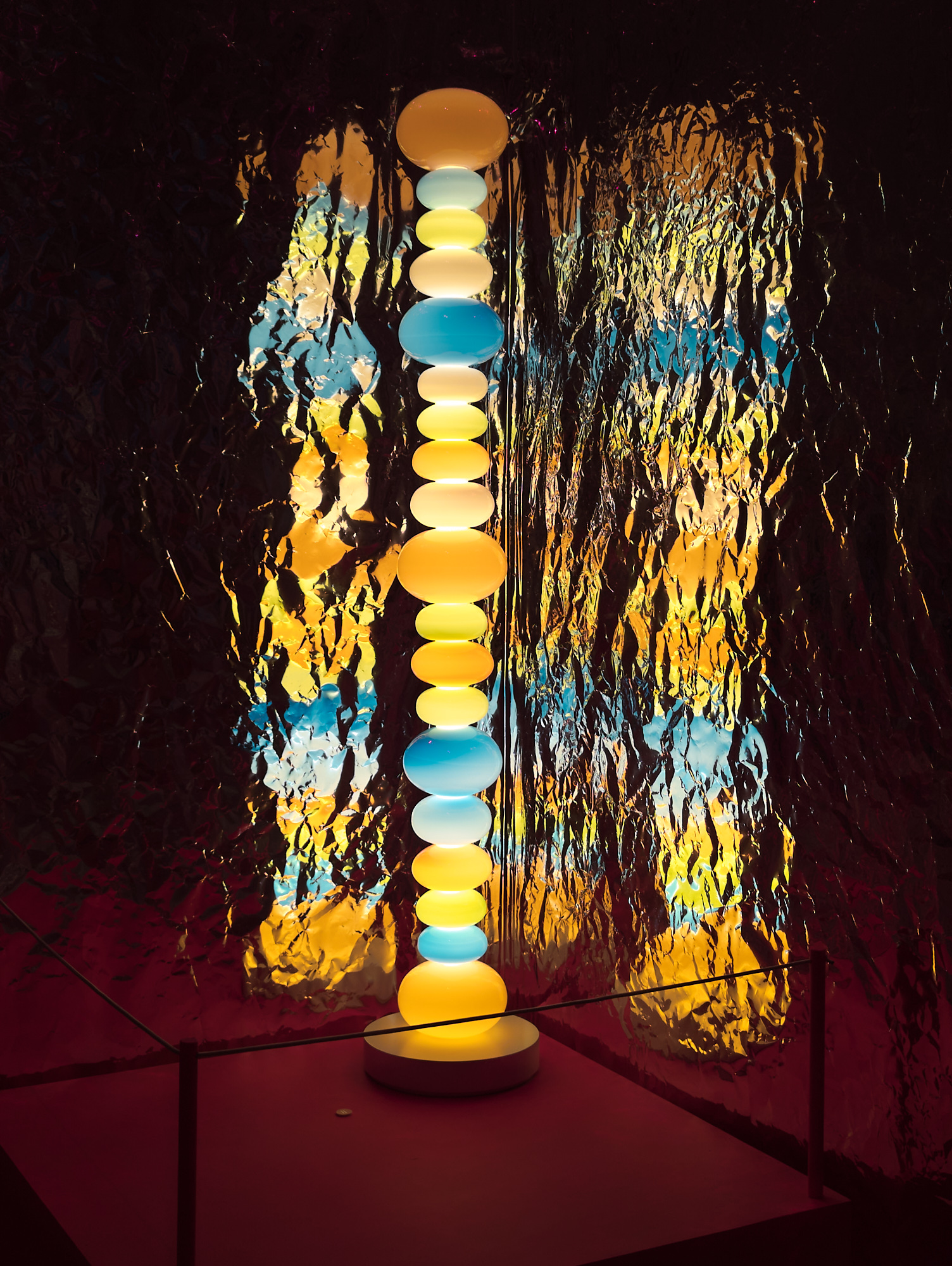

The final room of the show does hint at this wider context, but very safely so. There is the image of Vogue’s special Barbie issue, a picture of Andy Warhol with a gigantic Barbie face, the time Barbie made the cover of Time magazine, and some costumes used from the recent film version of the doll. Also here is a Glowbule light designed by Adam Nathaniel Furman and made by Curiosa & Curiosa, as featured in the Greta Gerwig movie.

But this space, as welcome as it is to briefly burst the Matell bubble, doesn’t really critique or question anything in the way one may hope a curated Design Museum exhibition might to. Artists have, however, used the doll to discuss wider issues. Nancy Burson made a Polaroid photograph in which Barbie had visibly aged, with wrinkles. E.V. Day created a series of mummified Barbies, speaking to society’s dehumanising mythology of women in culture. Emiliano Paolini and Marianela Perelli took shop-bought dolls and dressed them in overtly religious clothing to create beatified Barbies. In 1993, the Barbie Liberation Organization, an underground network of artists, swapped the voice boxes of Teen Talk Barbies with Hasbro’s talking GI Joe action figures, then popped them back onto the shelves of shops for children to unexpectedly explore gender stereotypes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

It is a shame that there wasn’t more room for the world of Barbie outside of Mattel’s control, as exhibitions that are so tightly made in collaboration with a single designer or manufacturer veer dangerously close to working more as a PR advertorial exercise than a cultural or museum exploration of a subject. Barbie is perhaps rescued from this fate by the overarching design of Sam Jacob Studio which while sticking to the bubblegum colours of the doll and her life, but twisting it artfully into a maximal world that not only picks up on the doll stylistically, in some places uses it as material – a chandelier formed of three types of Barbie hair is great fun.

The Design Museum’s exhibition shows there’s much, much more to Barbie than a plastic body and some fashion accessories. She has a whole world of interests, including a seemingly rich knowledge of architectural history and interior design. As witnessed through some of the 180+ dolls on display, Barbie has had many careers since 1959 including as a political campaigner, primary school teacher, nurse, pasta chef, and eco-leader. In 2011 she came out as an architect, with a dress suggesting the New York skyline in diamondesque dots, a plastic drawing tube flung over her shoulder, and shoes totally impractical for a site visit. The Barbie exhibition perhaps suggests she should return to it as her prime career, as of the hundreds of jobs she’s had over her life she shows a passion for buildings and furniture perhaps only surpassed by her focus on fashion.

Barbie was born in 1959 when Ruth Handler of Mattel launched the “teen age fashion model” at New York Toy Fair. The very first Barbie welcomes visitors to the Design Museum show, albeit safely ensconced in a Perspex vitrine, in a black and white stripey number, one of a number of interchangeable outfits made for her. She was homeless until 1962 when her first Dreamhouse was constructed, the first of several abodes that have enabled her to stay at the height of cultural and architectural fashion.

That first Dreamhouse is also presented in the exhibition, in a central room that is a suburban sprawl of former Barbie homes. Her first was made of cardboard, a living space filled with mid-century furniture and the latest technological entertainment – though nowhere to cook. In 1968 she had entered her swinging period (stylistically, that is, Ken has been the main man in her life since 1961) and took ownership of a Family House with moulded furniture, a Carnaby Street sign on the wall, and hand-designed wallpaper with a sixties twist on Edwardian patterns.

Barbie has had quite an eclectic, and knowing, interest in architecture over the years. in 1978 she lived in an A-Frame Dreamhouse which looks not unlike early Frank Gehry modular architecture. By 2021 she had moved into brashly coloured three-storey open-plan update of mid-century modernism, complete with a slide into a pool.

The exhibition has a great number of other houses and interiors – from a 1962 couture showroom to the interior of a lunar space capsule. One section – wonderfully presented as if a street by Sam Jacob Studio, lined up against a golden-hour gradient accessed through an arch – presents a whole series of Barbie’s former homes. There are McMansion qualities to her 1990 Magical Mansion, complete with neoclassical columns and pink rooftiles. She also once owned a two-storey townhouse, a tiny cottage-like Family House with Palladian windows and vines, and a three-floor one-garage Dreamhouse from 2016 offer more nods to her interest in historic architecture through pilasters and pediments.

Elsewhere, we get to explore Barbie’s history of collecting classic design furniture. Chintzy and florally decorated beds, chairs, and tables from the 1980’s interest in traditional interior design can be seen in proximity to her 1998 Trendy Loft fitout, replete with inflatable chair, futon sofa, and lava lamp. There is a collaboration with Kartell with five of the company’s seminal Philippe Starck chairs remade at her scale in a shocking pink.

The exhibition leans heavily upon Mattel’s endorsement and archive – there is little space in the presentation for critique about gender roles, body politics except for how it celebrates the toymaker’s changes and notional progressive changes to their designs and processes. This does mean there are lots of fantastic examples of Barbie and her attachments from across the decades, but the visitor is never allowed to leave the Barbie world created to consider the doll and its roll in society and culture more critically.

The final room of the show does hint at this wider context, but very safely so. There is the image of Vogue’s special Barbie issue, a picture of Andy Warhol with a gigantic Barbie face, the time Barbie made the cover of Time magazine, and some costumes used from the recent film version of the doll. Also here is a Glowbule light designed by Adam Nathaniel Furman and made by Curiosa & Curiosa, as featured in the Greta Gerwig movie.

But this space, as welcome as it is to briefly burst the Matell bubble, doesn’t really critique or question anything in the way one may hope a curated Design Museum exhibition might to. Artists have, however, used the doll to discuss wider issues. Nancy Burson made a Polaroid photograph in which Barbie had visibly aged, with wrinkles. E.V. Day created a series of mummified Barbies, speaking to society’s dehumanising mythology of women in culture. Emiliano Paolini and Marianela Perelli took shop-bought dolls and dressed them in overtly religious clothing to create beatified Barbies. In 1993, the Barbie Liberation Organization, an underground network of artists, swapped the voice boxes of Teen Talk Barbies with Hasbro’s talking GI Joe action figures, then popped them back onto the shelves of shops for children to unexpectedly explore gender stereotypes.

It is a shame that there wasn’t more room for the world of Barbie outside of Mattel’s control, as exhibitions that are so tightly made in collaboration with a single designer or manufacturer veer dangerously close to working more as a PR advertorial exercise than a cultural or museum exploration of a subject. Barbie is perhaps rescued from this fate by the overarching design of Sam Jacob Studio which while sticking to the bubblegum colours of the doll and her life, but twisting it artfully into a maximal world that not only picks up on the doll stylistically, in some places uses it as material – a chandelier formed of three types of Barbie hair is great fun.

The Design Museum’s exhibition shows there’s much, much more to Barbie than a plastic body and some fashion accessories. She has a whole world of interests, including a seemingly rich knowledge of architectural history and interior design. As witnessed through some of the 180+ dolls on display, Barbie has had many careers since 1959 including as a political campaigner, primary school teacher, nurse, pasta chef, and eco-leader. In 2011 she came out as an architect, with a dress suggesting the New York skyline in diamondesque dots, a plastic drawing tube flung over her shoulder, and shoes totally impractical for a site visit. The Barbie exhibition perhaps suggests she should return to it as her prime career, as of the hundreds of jobs she’s had over her life she shows a passion for buildings and furniture perhaps only surpassed by her focus on fashion.