Damien Hirst & his civilisation ending cultural grey goo

Damien Hirst’s latest series of paintings is being shown by

Heni at Phillips in London with over thirty large canvases depicting urban

scenes covered with bright nature, which the artist claims is a study of

civilisation painted “optimistically, like ice cream.” But things don’t seem

right in the cities Hirst has conjured, so Will Jennings looked a bit closer at

the scenes to see what it all might really mean.

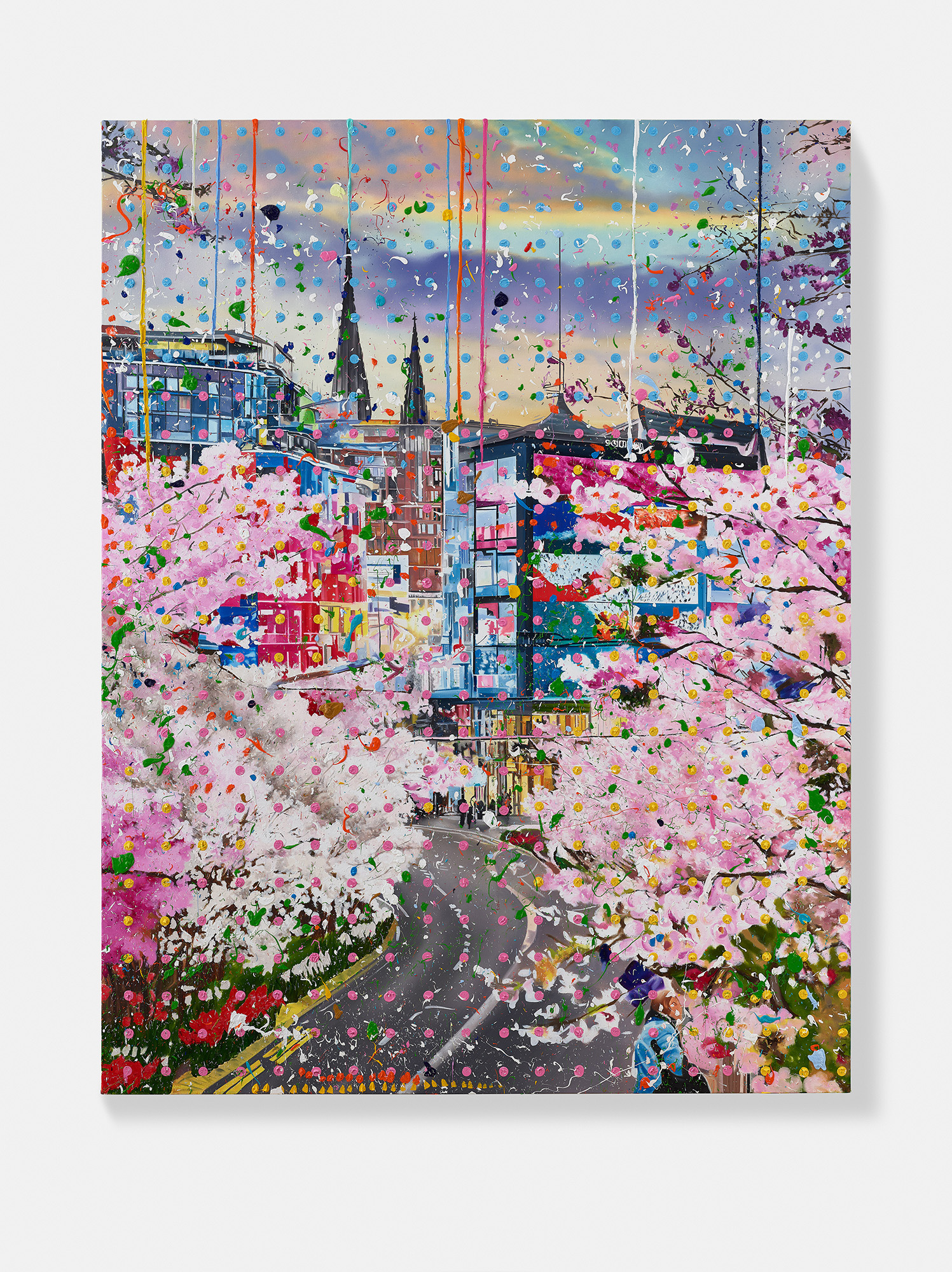

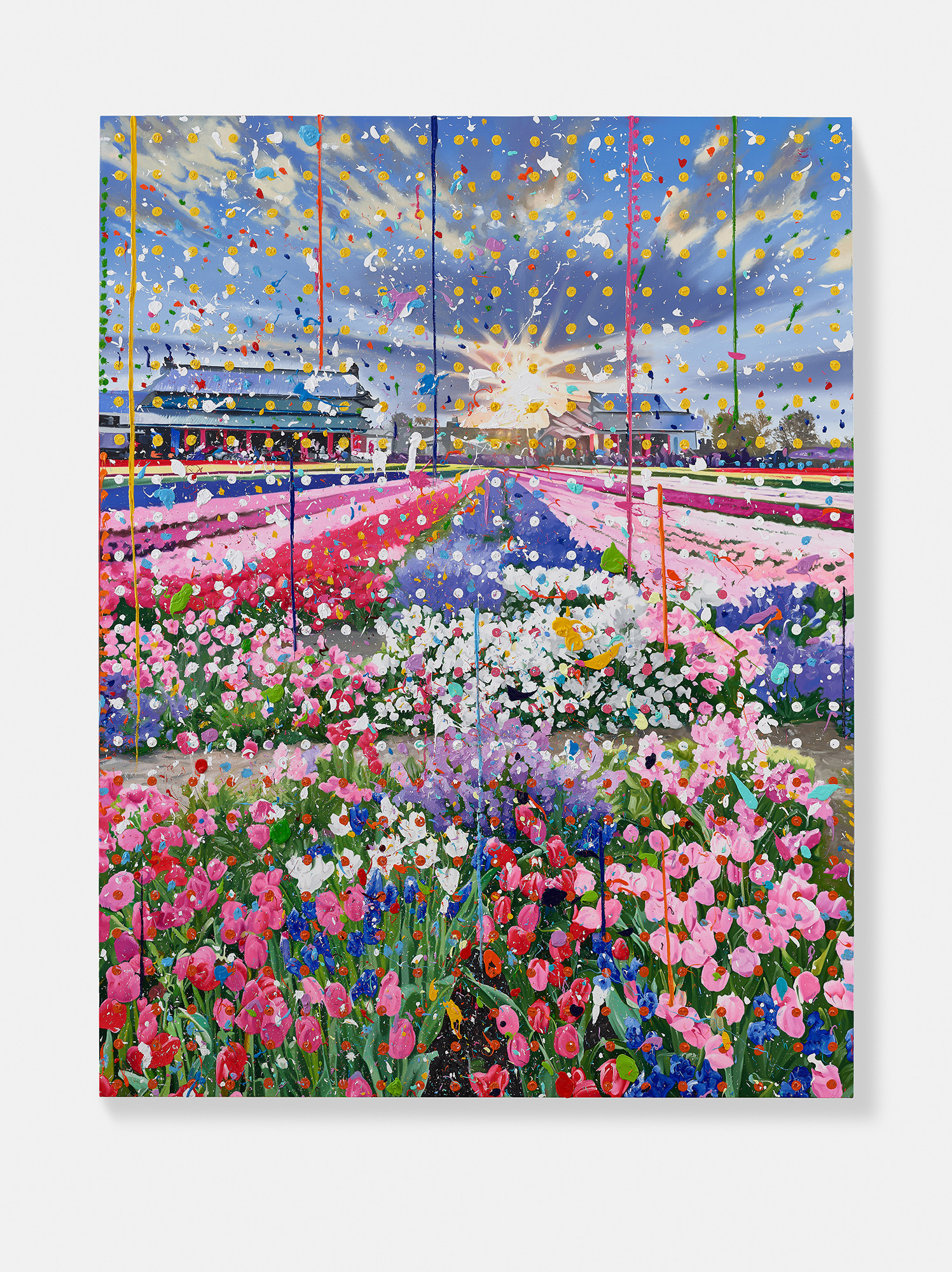

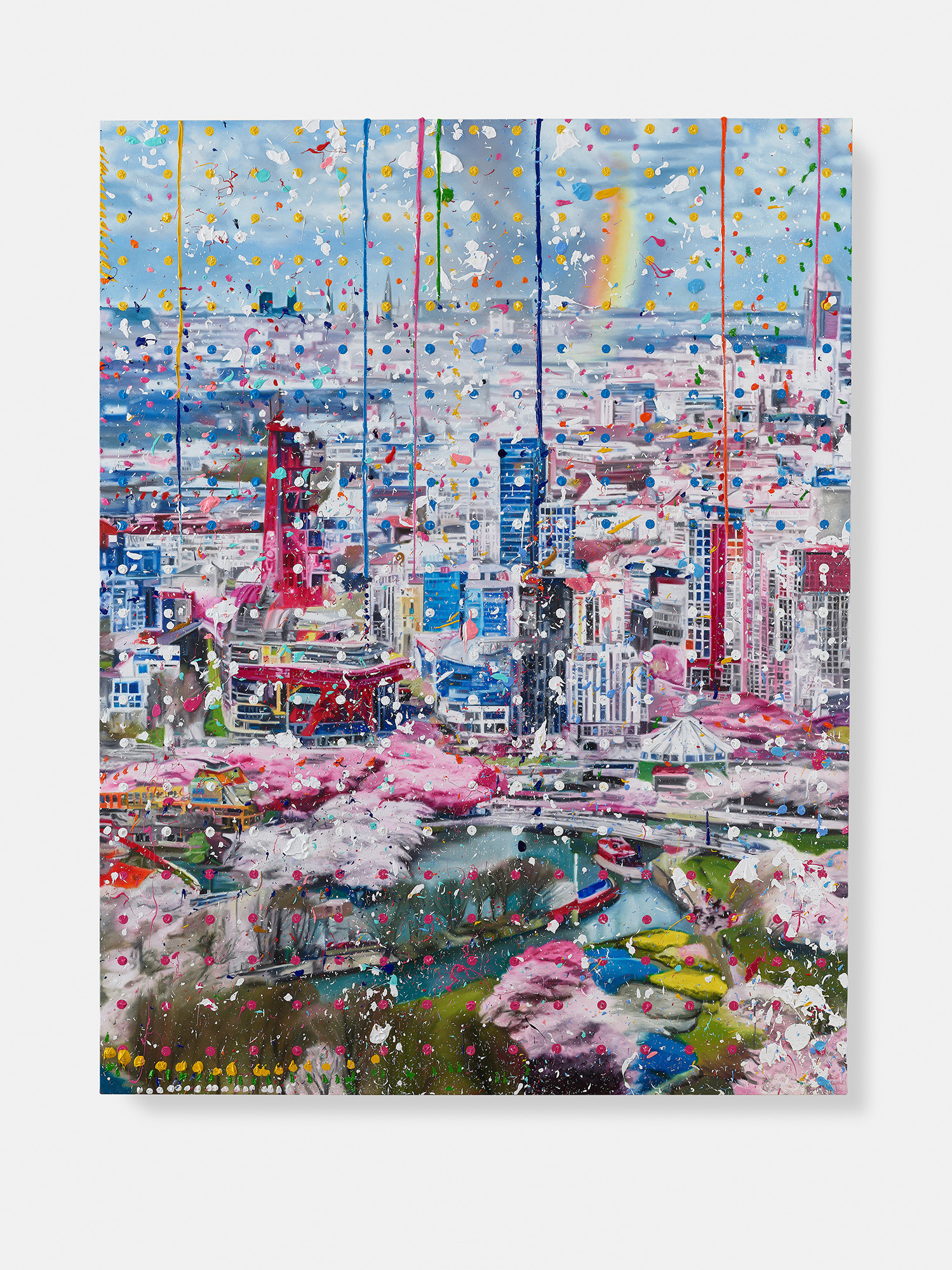

There are countless other worlds depicted in the tall canvases,

filling the taller galleries of Phillips in Mayfair, central London. At first

glance, the scenes seem halcyonic. A golden hour hue illuminating recognisable

urban and semi-urban cityscapes, each viewed from a distance, bucolic greenery,

blossoming trees, and flowering fauna filling the space between us and the busy

cities. There, through a confetti dance of colour, is a rainbow. There, behind romantically

towering spires of twin churches is a glowing sun.

![]()

![]()

There are buildings that seem familiar. Is that the peak of Liverpool’s Metropolitan Cathedral? colour grid of a modernist block, could that be Unite d’habitation, or perhaps Park Hill? Another cathedral, perhaps that’s Salisbury? But, there are two spires, that doesn’t seem right, and they’re too far apart to be Cologne, in any case there’s a weird neoclassical domed building to one side.

A uniformity covers it all. In every painting the foreground is dominated by brightly coloured nature, in most there is a visual desire line leading from us, the viewers, towards the central focus of the distant view – a dirt path, a floral furrow, or a tarmac road with brightly planted embankments leading towards us away from the city. The scene in every canvas is covered in a dotted grid, somewhat slapdash in style, with a certain messiness celebrated and disguised by further paint splashes flicked and jerked across the vista. The works are by Damien Hirst, the spatter becoming something of a trademark aesthetic to his recent series of paintings, the dots a not-very-subtle reference to the dot paintings he is well-known for and has been producing in various forms since 1988.

“He has never not been a painter,” writes Norman Rosenthal, former director of the Royal Academy in his introductory remarks for the thick and richly produced catalogue accompanying Hirst’s newest series of paintings, The Civilisation Paintings. Rosenthal, was present when Hirst organised the seminal 1988 Freeze exhibition of Goldsmiths graduates, launching the YBA movement, and has been a valuable ally since, including him in the celebrated 1998 Sensation exhibition and contributing to various Hirst-adjacent books and essays since.

At Frieze London in 2023 Gagosian gallery presented a Hirst series of paintings, The Secret Gardens, large canvases depicting rather chaotic flowery messes in which flora mingled with paintsplats. They were the talk of the art fair, if by talk you mean embarrassed whispers from artworld punters asking if others had seen what they had just seen. Writing in the Guardian, Jonathan Jones said the paintings forged “an unutterable sadness” and that: “He still shows absolutely no talent for painting the real world … He is still bad, flat and unimaginative…”. Apollo wrote that it was “a nadir for the once-exciting artist: straightforward pictures of straightforward flowers zhuzhed up, almost as an afterthought, by a final layer of Action painting-ish splatters.” Artnet included the works on their 6 worst of the year list.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The longer spent looking into the Civilisation paintings, the more the depicted other worlds seem increasingly other. Something is not right. None of those architectural details that at half glance seemed recognisable remain reliable at closer inspection. And when really paying attention, the entire scenes seem composed of nonsense: generic modern-ish buildings but with no cohesive language or sense of urban fabric, architectural details that don’t align, join up, or make any structural sense, and the cars that can be seem to be driving in the same direction on both sides of the road. The closer you look, the more the whole thing descends into chaos and becomes the true impossible non-place of Thomas More’s Utopia, with the conjoined dystopia wrapped up within.

The exhibition’s A4 handout has a quote from hirst that concludes: “These paintings are about our civilisations today. I wanted them to feel fantastical and chaotic and on the edge of destruction. It’s often hard to have hope or romanticise about our current landscape or our civilisations but we must have hope, no matter how dark the world gets. But to distract from the nihilism and hate, I tried to paint them optimistically, like ice cream.”

As artist statements go, it’s one of the more hilarious, and doesn’t offer much information about the architectures and cities present. For that, the thick and richly produced accompanying catalogue helps, featuring a long interview between Hirst and writer James Fox – one more than once doesn’t show the artist, his practice, or professional relationship to his staff in very good light, to the point it’s feels surprising nobody responsible interjected to make edits. In it, he explains:

“I took this picture in my studio of two of the Secret Gardens paintings, which are AI anyway. I never spoke about AI when I made them. I thought, it’s all so tacky and so new, people are all jumping on bandwagons. And for me it’s not about AI, with found images and search words. When I finished two paintings, I loved the colour and I took that photograph, and because there was something about it that looked like buildings, it generated all these crazy images of cities. I never took a photograph of a city. I just had two paintings in my studio on the floor with paint, away from everything, and that image in the generators started fucking giving me images of cities.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

Suddenly, the glitches and nonsense all make sense – the cityscapes are derived from garbage AI, not creative or rational human processes. In his recent article for recessed.space, Neural networks & the architectural imagination (see 00186) Matthew Lloyd Roberts wrote of the use of AI-generate images in architectural design: “It relies upon, iterates, and reproduces a visual mode established by human hand, but it is inescapably mimetic of human image-making.” AI cannot understand what it is representing, but only pattern-organise spatial and colour elements often found in proximity to one another within the vast datasets it has scraped. It cannot think with originality, so much as only reinterpret and fold together that which has gone before. It is, ultimately, stupid. Yes, the images seem to be “fantastical and chaotic and on the edge of destruction,” but in the works these words don’t seem to align to anything civilisational, architectural, or within the conceptual subject of that which is depicted, but more to Hirst’s fractured relationship to culture, craft, creativity, and artistic process.

There is an hilarious video on the TikTok channel of Heni (watch it HERE), a young technology company that has found a niche creating prints, books, and NFTs of living artists and dead artists’ estates. It is Heni that are behind this presentation of The Civilisation Paintings, albeit with the support of the artist’s galleries Gagosian and White Cube. In the video Hirst prowls around a large studio space, lined with around 25 of the large canvases now seen in the show. With a determined stare he moves across the floor covered with paint marks somewhat akin to Francis Bacon’s celebrated, chaotic studio. He approaches a central table full of large tubs of paint, grabs a brush sticking out of stark yellow, looks at a number of paintings as if deciding his prey, then takes the brush to one of the canvases and draws a slow, vertical yellow line down its surface. All the time his heavy breathing and staring eyes tell you that this is a serious artist doing serious art, and that the carefully placed yellow line is full of serious meaning.

The whole one minute of the TikTok recording is choreographed, performed, and downright silly, but insightful comments underneath help puncture the pomp: “Was Tony Soprano recording the heavy breathing?” “The Saltbae of the art world!” “Is he pretending to paint his own paintings?” “Get all the artists out of the room, Damien needs to come in and do a social post.” “He doesn’t paint his own paintings, hasn’t for years.” “Interns create his paintings. I had a friend do it years ago. She never met him.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

While Hirst has only now admitted to the fact his 2023 Secret Garden paintings were rooted in AI, not mentioning its use to viewers, writers, or buyers at the time, one part of his process he has never shied away from is acknowledging that he doesn’t personally make his own artworks, and as TikTok commenters suggested, this is also the case with his paintings.

“To put it simply,” he explains to Fox, “you put an image in and then you give it some prompts or word suggestions and it starts generating images. There’s a lot of trial and error, many false starts, but the possibilities are limitless. And when I have generated these images, I paint them, or I get my … assistants to paint them.”

The catalogue lists the words and phrases Hirst flooded the AI with to create the Civilisation scenes, including: bright summer flowers; Sunlight; Daffodils; tulips; cherry blossoms; pinky pink flowers; red flowers blue flowers pretty pink flowers colourful; amazing colours!; explosions war destruction fire; smashed buildings; dabby brushmarks; pointillism;painterly colour areas; big gestural painting; explosions war destruction; fire; smashed buildings; exploding broken jungle vines magic; bright summer flowers; exploding nature.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hirst explains his process to Fox, one in which he “can spend all day doing a thousand images where it just regenerates and regenerates” images that are all “AI generated, then painted by my assistants very quickly.”

“Which bits do they paint?” Fox innocently asks.

“The whole thing’s painted. But I only give them a fixed time, sometimes only a week, to paint that whole image that I generate on AI – copying the AI image quickly using a projector.”

“But they’re having to be pretty good at that.”

“Well yeah, I trained them.” Hirst says, regarding his large workforce, in the main comprising skilled art school graduates and artists in their own right when not copying AI pap for Hirst.

Over a series of paragraphs, Hirst outlines his working relationship with his painters in which he verbally whips them into carrying out each AI painting not within the year they first estimated needing, but to complete each simulacra within one month. “And then they would panic and say, ‘You’re slave driving us!’” he explains, seemingly proud, then speaking at length wondering which creates the better worker: “painting assistants versus robots versus AI.”

![]()

![]()

Regarding the role of the architectural cultural worker in relation to the generation of AI architectural imagery, Lloyd-Roberts wrote: “Architectural practices pay their bills on the production of huge numbers of images: renderings and perspectives which woo clients and stakeholders through pitching and planning; detail drawings of how the bits and bobs fit together. … some practices rely heavily on the labour of architectural assistants and junior architects whose pay is kept very low compared to other fields with similar vocational qualifications. Many architectural offices possess a cultural expectation of overwork, to which young architects are often acclimatised during their university training.”

There seem to be interesting parallels with architectural workers and art workers creating Hirst’s pieces. When Fox asks how many assistants the artist has, Hirst replies: “I used to have sixty, but now I’ve got less because some people have left. I’ve got about twenty people now. It’s mainly in my studio in Devon.” One of those recent workers who left recently spoke to the Daily Mail as a whistleblower (HERE). They were involved in the dissecting and formaldehyding of animals, not painting, but they speak of a £22k salary, difficult working conditions, expectations of working late or weekend, and writing Hirst’s signature on works. “We would be warned he was coming in and told not to make eye contact, don’t look his way too much, don’t talk to him unless he spoke to us first. Sometimes we would text him a picture of something we had just made and he’d text back, ‘Great’, full stop. That was his involvement.”

The Daily Mail report that the whistleblowing worker, and 61 others, were made redundant from Hirst’s carcass factory after Hirst’s company, Science UK, had claimed £1.31m of government Covid furlough. In the same year, the article states, Science UK made £3.5m profit on sales of £18.2m of art sales.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hirst has connections to architecture beyond these AI-sourced paintings, and some of those huge annual profits support a property empire estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of pounds, including Toddington Manor in Gloucestershire, Winsham Farm in Devon where the artist hopes to build a 650-home development, a farmhouse nearby, and other homes in London including a £36m+ Regent’s Park mansion.

The artist bought the Victorian Toddington Manor in 2005. Then, like in Devon, he intended to construct a whole town of 750 homes, but instead the place has been left abandoned, covered in scaffolding and plastic sheeting for seventeen years, much to the annoyance of locals. The building remains on the Historic England Heritage At Risk register (HERE).

Perhaps Hirst’s decaying Toddington Manor was on his mind when the artist said to Fox: “…when you love in a house, everything’s great, it’s totally perfect. And then if you get old, and you stop looking after it, the windows crack and the vines come through the gaps in the door, and the outside comes in. And in a way the inside goes outside too. So a lot of the images seem to be nature twisting and growing and trying to cohabit environments with architecture.”

Hirst didn’t mention it though, instead he referenced a romantic recent trip to Angkor Wat where he saw “vines growing through the walls.” The paintings themselves, however, don’t carry this resonance. Time period aside – these paintings are unapologetically not rooted in ancient civilisations such as the Khmer complex, but in an assortment of somewhat bland nonplaces of neoliberal facades and developer-led masses – the nature in his paintings is formed of blossom-filled trees, manicured grass, and neat rows of flowers all in the foreground or leading towards the urban scene. Nature and architecture never actually intermingle, one sets the juxtaposing scene for the other. “You can feel civilisations dying as well as living, and how nature wraps around that,” Hirst states of his paintings, but there is no wrapping around in these prosaic sequential flat layering of the scenes, only depthless death and aesthetic components that bare no relationship or ecology with one another, with the only element that connects it all the purposeless lines and dots so performatively painted by Hirst himself over the top of other people’s work.

![]()

![]()

Hirst may state that these colourful works follow in the footsteps of Matisse, Bonnard, and Pablo Picasso – “I’ve tried to imagine those artists today and what they would paint, and how they would struggle to remain romantic in a complex and conflicted world filled with confounding issues and problems, but still filled hopefully with some wonder and excitement.” – but his paintings are simply not anywhere near the quality, compositional interest, or intellectual curiosity of even the most churned-out works by the three mentioned artists.

Because AI cannot understand what it is creating, and cannot contend with aesthetic or critical ideas that Matisse, Picasso – or even early Hirst – imagined and grappled with, meaning the imagery it makes is dull, flat, emotionless, nonsensical, and dead. Hirst cosplaying as a real artist and treading his Baconesque studio floor attacking each of the paintings his talented workers have carefully created with meaningless daubs, dots, lines, and lumps doesn’t add more meaning, profundity, or romance to the works, it only serves to emphasise the chasm between creativity and whatever this is.

In his essay about architecture and AI, Lloyd-Roberts wrote that “These parallel processes are symptoms of a crisis of confidence in our collective architectural imagination and in the market and regulatory processes which constitute the built environment. AI images produce the illusion of some kind of objectivity. Difficult decisions about what is built, where, by whom and for how much are sublimated into a model designed to produce convincing outputs.”

What, then, do Hirst’s AI-birthed Civilisation paintings say to his artistic imagination and market that they feed? Late in the Fox interview, Hirst says that the AI source images “are all from the collective imagination” – but AI doesn’t imagine, it creates averages. It takes vast amounts of data and predicts the most expected outcome for the text or image it is pumping out. Surely culture has higher ambitions? He continues:

“Suddenly I’m in a position where I can generate so many more amazing paintings than I can off my own steam,” Hirst says of his flirting with AI and robotic reproduction technologies. “It’s not a question of how many you should make, it’s about how many you shouldn’t make?”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Grey goo theory is a hypothetical world-ending sci-fi scenario in which uncontrolled self-replicating machines consume everything in nature as they attempt to replicate and reproduce. The Civilisation Paintings are perhaps an important step in the development of cultural grey goo, the mundanity and averaging of AI deeply and cynically replacing artistic process, at the expense of human labour, cultural ambition, critical idea, or aesthetic interest. Perhaps The Civilisation Paintings represent a moment when Hirst stopped being an artist and simply became a picture-maker, just as AI-fuelled architecture that dehumanises the process, deskills workers, and averages out creative ambition is no longer architecture, but building.

His flowers series from Frieze London sold as soon as the fair had opened, and his Cherry Blossom paintings were made just in time for his first solo show in Japan as Cherry Blossom season started. These too, will no doubt sell well in paint and print form due to the Hirst brand still holding investment value, but money can only be the driver for such mind-numbingly boring works. The current global AI drive is sucking up money (and energy) in its search for purpose and promise for companies to lay off staff, and in doing so relentlessly shows how unremarkable and uninteresting its output is. This is, perhaps, a similar trajectory to Damien Hirst, seemingly on a quest to keep pushing the idea his boringly average product is worth investing in, whilst deskilling and laying off workers who evidently have actual skills and creative passion.

The AI is evidently not the only algorithm at play here. These paintings will sell well, and Heni will make handsome profits through the selling of prints. It makes sense that he is self-referencing his recent top-selling works into this new auto-generated output before laying over the additional and performative self-reference painted dots. Hirst himself has become an algorithmic generator, no longer interested in idea, ambition, or creativity, just churning remarkably average and banal content that, like the buildings in the Civilisation series, simply makes no critical or artistic sense when considered up close.

![]()

figs.i,ii

There are buildings that seem familiar. Is that the peak of Liverpool’s Metropolitan Cathedral? colour grid of a modernist block, could that be Unite d’habitation, or perhaps Park Hill? Another cathedral, perhaps that’s Salisbury? But, there are two spires, that doesn’t seem right, and they’re too far apart to be Cologne, in any case there’s a weird neoclassical domed building to one side.

A uniformity covers it all. In every painting the foreground is dominated by brightly coloured nature, in most there is a visual desire line leading from us, the viewers, towards the central focus of the distant view – a dirt path, a floral furrow, or a tarmac road with brightly planted embankments leading towards us away from the city. The scene in every canvas is covered in a dotted grid, somewhat slapdash in style, with a certain messiness celebrated and disguised by further paint splashes flicked and jerked across the vista. The works are by Damien Hirst, the spatter becoming something of a trademark aesthetic to his recent series of paintings, the dots a not-very-subtle reference to the dot paintings he is well-known for and has been producing in various forms since 1988.

“He has never not been a painter,” writes Norman Rosenthal, former director of the Royal Academy in his introductory remarks for the thick and richly produced catalogue accompanying Hirst’s newest series of paintings, The Civilisation Paintings. Rosenthal, was present when Hirst organised the seminal 1988 Freeze exhibition of Goldsmiths graduates, launching the YBA movement, and has been a valuable ally since, including him in the celebrated 1998 Sensation exhibition and contributing to various Hirst-adjacent books and essays since.

At Frieze London in 2023 Gagosian gallery presented a Hirst series of paintings, The Secret Gardens, large canvases depicting rather chaotic flowery messes in which flora mingled with paintsplats. They were the talk of the art fair, if by talk you mean embarrassed whispers from artworld punters asking if others had seen what they had just seen. Writing in the Guardian, Jonathan Jones said the paintings forged “an unutterable sadness” and that: “He still shows absolutely no talent for painting the real world … He is still bad, flat and unimaginative…”. Apollo wrote that it was “a nadir for the once-exciting artist: straightforward pictures of straightforward flowers zhuzhed up, almost as an afterthought, by a final layer of Action painting-ish splatters.” Artnet included the works on their 6 worst of the year list.

figs.iii-v

The longer spent looking into the Civilisation paintings, the more the depicted other worlds seem increasingly other. Something is not right. None of those architectural details that at half glance seemed recognisable remain reliable at closer inspection. And when really paying attention, the entire scenes seem composed of nonsense: generic modern-ish buildings but with no cohesive language or sense of urban fabric, architectural details that don’t align, join up, or make any structural sense, and the cars that can be seem to be driving in the same direction on both sides of the road. The closer you look, the more the whole thing descends into chaos and becomes the true impossible non-place of Thomas More’s Utopia, with the conjoined dystopia wrapped up within.

The exhibition’s A4 handout has a quote from hirst that concludes: “These paintings are about our civilisations today. I wanted them to feel fantastical and chaotic and on the edge of destruction. It’s often hard to have hope or romanticise about our current landscape or our civilisations but we must have hope, no matter how dark the world gets. But to distract from the nihilism and hate, I tried to paint them optimistically, like ice cream.”

As artist statements go, it’s one of the more hilarious, and doesn’t offer much information about the architectures and cities present. For that, the thick and richly produced accompanying catalogue helps, featuring a long interview between Hirst and writer James Fox – one more than once doesn’t show the artist, his practice, or professional relationship to his staff in very good light, to the point it’s feels surprising nobody responsible interjected to make edits. In it, he explains:

“I took this picture in my studio of two of the Secret Gardens paintings, which are AI anyway. I never spoke about AI when I made them. I thought, it’s all so tacky and so new, people are all jumping on bandwagons. And for me it’s not about AI, with found images and search words. When I finished two paintings, I loved the colour and I took that photograph, and because there was something about it that looked like buildings, it generated all these crazy images of cities. I never took a photograph of a city. I just had two paintings in my studio on the floor with paint, away from everything, and that image in the generators started fucking giving me images of cities.”

figs.vi-viii

Suddenly, the glitches and nonsense all make sense – the cityscapes are derived from garbage AI, not creative or rational human processes. In his recent article for recessed.space, Neural networks & the architectural imagination (see 00186) Matthew Lloyd Roberts wrote of the use of AI-generate images in architectural design: “It relies upon, iterates, and reproduces a visual mode established by human hand, but it is inescapably mimetic of human image-making.” AI cannot understand what it is representing, but only pattern-organise spatial and colour elements often found in proximity to one another within the vast datasets it has scraped. It cannot think with originality, so much as only reinterpret and fold together that which has gone before. It is, ultimately, stupid. Yes, the images seem to be “fantastical and chaotic and on the edge of destruction,” but in the works these words don’t seem to align to anything civilisational, architectural, or within the conceptual subject of that which is depicted, but more to Hirst’s fractured relationship to culture, craft, creativity, and artistic process.

There is an hilarious video on the TikTok channel of Heni (watch it HERE), a young technology company that has found a niche creating prints, books, and NFTs of living artists and dead artists’ estates. It is Heni that are behind this presentation of The Civilisation Paintings, albeit with the support of the artist’s galleries Gagosian and White Cube. In the video Hirst prowls around a large studio space, lined with around 25 of the large canvases now seen in the show. With a determined stare he moves across the floor covered with paint marks somewhat akin to Francis Bacon’s celebrated, chaotic studio. He approaches a central table full of large tubs of paint, grabs a brush sticking out of stark yellow, looks at a number of paintings as if deciding his prey, then takes the brush to one of the canvases and draws a slow, vertical yellow line down its surface. All the time his heavy breathing and staring eyes tell you that this is a serious artist doing serious art, and that the carefully placed yellow line is full of serious meaning.

The whole one minute of the TikTok recording is choreographed, performed, and downright silly, but insightful comments underneath help puncture the pomp: “Was Tony Soprano recording the heavy breathing?” “The Saltbae of the art world!” “Is he pretending to paint his own paintings?” “Get all the artists out of the room, Damien needs to come in and do a social post.” “He doesn’t paint his own paintings, hasn’t for years.” “Interns create his paintings. I had a friend do it years ago. She never met him.”

figs.ix-xiii

While Hirst has only now admitted to the fact his 2023 Secret Garden paintings were rooted in AI, not mentioning its use to viewers, writers, or buyers at the time, one part of his process he has never shied away from is acknowledging that he doesn’t personally make his own artworks, and as TikTok commenters suggested, this is also the case with his paintings.

“To put it simply,” he explains to Fox, “you put an image in and then you give it some prompts or word suggestions and it starts generating images. There’s a lot of trial and error, many false starts, but the possibilities are limitless. And when I have generated these images, I paint them, or I get my … assistants to paint them.”

The catalogue lists the words and phrases Hirst flooded the AI with to create the Civilisation scenes, including: bright summer flowers; Sunlight; Daffodils; tulips; cherry blossoms; pinky pink flowers; red flowers blue flowers pretty pink flowers colourful; amazing colours!; explosions war destruction fire; smashed buildings; dabby brushmarks; pointillism;painterly colour areas; big gestural painting; explosions war destruction; fire; smashed buildings; exploding broken jungle vines magic; bright summer flowers; exploding nature.

figs.xiv-xvi

Hirst explains his process to Fox, one in which he “can spend all day doing a thousand images where it just regenerates and regenerates” images that are all “AI generated, then painted by my assistants very quickly.”

“Which bits do they paint?” Fox innocently asks.

“The whole thing’s painted. But I only give them a fixed time, sometimes only a week, to paint that whole image that I generate on AI – copying the AI image quickly using a projector.”

“But they’re having to be pretty good at that.”

“Well yeah, I trained them.” Hirst says, regarding his large workforce, in the main comprising skilled art school graduates and artists in their own right when not copying AI pap for Hirst.

Over a series of paragraphs, Hirst outlines his working relationship with his painters in which he verbally whips them into carrying out each AI painting not within the year they first estimated needing, but to complete each simulacra within one month. “And then they would panic and say, ‘You’re slave driving us!’” he explains, seemingly proud, then speaking at length wondering which creates the better worker: “painting assistants versus robots versus AI.”

figs.xvii,xviii

Regarding the role of the architectural cultural worker in relation to the generation of AI architectural imagery, Lloyd-Roberts wrote: “Architectural practices pay their bills on the production of huge numbers of images: renderings and perspectives which woo clients and stakeholders through pitching and planning; detail drawings of how the bits and bobs fit together. … some practices rely heavily on the labour of architectural assistants and junior architects whose pay is kept very low compared to other fields with similar vocational qualifications. Many architectural offices possess a cultural expectation of overwork, to which young architects are often acclimatised during their university training.”

There seem to be interesting parallels with architectural workers and art workers creating Hirst’s pieces. When Fox asks how many assistants the artist has, Hirst replies: “I used to have sixty, but now I’ve got less because some people have left. I’ve got about twenty people now. It’s mainly in my studio in Devon.” One of those recent workers who left recently spoke to the Daily Mail as a whistleblower (HERE). They were involved in the dissecting and formaldehyding of animals, not painting, but they speak of a £22k salary, difficult working conditions, expectations of working late or weekend, and writing Hirst’s signature on works. “We would be warned he was coming in and told not to make eye contact, don’t look his way too much, don’t talk to him unless he spoke to us first. Sometimes we would text him a picture of something we had just made and he’d text back, ‘Great’, full stop. That was his involvement.”

The Daily Mail report that the whistleblowing worker, and 61 others, were made redundant from Hirst’s carcass factory after Hirst’s company, Science UK, had claimed £1.31m of government Covid furlough. In the same year, the article states, Science UK made £3.5m profit on sales of £18.2m of art sales.

figs.xix-xxi

Hirst has connections to architecture beyond these AI-sourced paintings, and some of those huge annual profits support a property empire estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of pounds, including Toddington Manor in Gloucestershire, Winsham Farm in Devon where the artist hopes to build a 650-home development, a farmhouse nearby, and other homes in London including a £36m+ Regent’s Park mansion.

The artist bought the Victorian Toddington Manor in 2005. Then, like in Devon, he intended to construct a whole town of 750 homes, but instead the place has been left abandoned, covered in scaffolding and plastic sheeting for seventeen years, much to the annoyance of locals. The building remains on the Historic England Heritage At Risk register (HERE).

Perhaps Hirst’s decaying Toddington Manor was on his mind when the artist said to Fox: “…when you love in a house, everything’s great, it’s totally perfect. And then if you get old, and you stop looking after it, the windows crack and the vines come through the gaps in the door, and the outside comes in. And in a way the inside goes outside too. So a lot of the images seem to be nature twisting and growing and trying to cohabit environments with architecture.”

Hirst didn’t mention it though, instead he referenced a romantic recent trip to Angkor Wat where he saw “vines growing through the walls.” The paintings themselves, however, don’t carry this resonance. Time period aside – these paintings are unapologetically not rooted in ancient civilisations such as the Khmer complex, but in an assortment of somewhat bland nonplaces of neoliberal facades and developer-led masses – the nature in his paintings is formed of blossom-filled trees, manicured grass, and neat rows of flowers all in the foreground or leading towards the urban scene. Nature and architecture never actually intermingle, one sets the juxtaposing scene for the other. “You can feel civilisations dying as well as living, and how nature wraps around that,” Hirst states of his paintings, but there is no wrapping around in these prosaic sequential flat layering of the scenes, only depthless death and aesthetic components that bare no relationship or ecology with one another, with the only element that connects it all the purposeless lines and dots so performatively painted by Hirst himself over the top of other people’s work.

figs.xxii,xxiii

Hirst may state that these colourful works follow in the footsteps of Matisse, Bonnard, and Pablo Picasso – “I’ve tried to imagine those artists today and what they would paint, and how they would struggle to remain romantic in a complex and conflicted world filled with confounding issues and problems, but still filled hopefully with some wonder and excitement.” – but his paintings are simply not anywhere near the quality, compositional interest, or intellectual curiosity of even the most churned-out works by the three mentioned artists.

Because AI cannot understand what it is creating, and cannot contend with aesthetic or critical ideas that Matisse, Picasso – or even early Hirst – imagined and grappled with, meaning the imagery it makes is dull, flat, emotionless, nonsensical, and dead. Hirst cosplaying as a real artist and treading his Baconesque studio floor attacking each of the paintings his talented workers have carefully created with meaningless daubs, dots, lines, and lumps doesn’t add more meaning, profundity, or romance to the works, it only serves to emphasise the chasm between creativity and whatever this is.

In his essay about architecture and AI, Lloyd-Roberts wrote that “These parallel processes are symptoms of a crisis of confidence in our collective architectural imagination and in the market and regulatory processes which constitute the built environment. AI images produce the illusion of some kind of objectivity. Difficult decisions about what is built, where, by whom and for how much are sublimated into a model designed to produce convincing outputs.”

What, then, do Hirst’s AI-birthed Civilisation paintings say to his artistic imagination and market that they feed? Late in the Fox interview, Hirst says that the AI source images “are all from the collective imagination” – but AI doesn’t imagine, it creates averages. It takes vast amounts of data and predicts the most expected outcome for the text or image it is pumping out. Surely culture has higher ambitions? He continues:

“Suddenly I’m in a position where I can generate so many more amazing paintings than I can off my own steam,” Hirst says of his flirting with AI and robotic reproduction technologies. “It’s not a question of how many you should make, it’s about how many you shouldn’t make?”

figs.xxiv-xxiii

Grey goo theory is a hypothetical world-ending sci-fi scenario in which uncontrolled self-replicating machines consume everything in nature as they attempt to replicate and reproduce. The Civilisation Paintings are perhaps an important step in the development of cultural grey goo, the mundanity and averaging of AI deeply and cynically replacing artistic process, at the expense of human labour, cultural ambition, critical idea, or aesthetic interest. Perhaps The Civilisation Paintings represent a moment when Hirst stopped being an artist and simply became a picture-maker, just as AI-fuelled architecture that dehumanises the process, deskills workers, and averages out creative ambition is no longer architecture, but building.

His flowers series from Frieze London sold as soon as the fair had opened, and his Cherry Blossom paintings were made just in time for his first solo show in Japan as Cherry Blossom season started. These too, will no doubt sell well in paint and print form due to the Hirst brand still holding investment value, but money can only be the driver for such mind-numbingly boring works. The current global AI drive is sucking up money (and energy) in its search for purpose and promise for companies to lay off staff, and in doing so relentlessly shows how unremarkable and uninteresting its output is. This is, perhaps, a similar trajectory to Damien Hirst, seemingly on a quest to keep pushing the idea his boringly average product is worth investing in, whilst deskilling and laying off workers who evidently have actual skills and creative passion.

The AI is evidently not the only algorithm at play here. These paintings will sell well, and Heni will make handsome profits through the selling of prints. It makes sense that he is self-referencing his recent top-selling works into this new auto-generated output before laying over the additional and performative self-reference painted dots. Hirst himself has become an algorithmic generator, no longer interested in idea, ambition, or creativity, just churning remarkably average and banal content that, like the buildings in the Civilisation series, simply makes no critical or artistic sense when considered up close.

fig.xxix

Damien Hirst was born in Bristol, England, and lives and works in London, Devon, and Gloucestershire, England. Collections include the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina,

Naples, Italy; Museum Brandhorst, Munich; Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, Madrid; Tate, London; Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo; Gallery of Modern Art,

Glasgow, Scotland; National Centre for Contemporary Arts, Moscow; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; Art Institute of Chicago; The

Broad, Los Angeles; Museo Jumex, Mexico City; and 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan.

Exhibitions include Cornucopia, Oceanographic Museum of Monaco (2010); Tate Modern, London (2012); Relics, Qatar Museums Authority, Al Riwaq (2013); Signification (Hope, Immortality and

Death in Paris, Now and Then), Deyrolle, Paris (2014); Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo (2015); The Last Supper, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (2016); Treasures from the Wreck of the

Unbelievable, Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana, Venice (2017); Damien Hirst at Houghton Hall: Colour Space Paintings and Outdoor Sculptures, Houghton Hall, Norfolk, England (2019); Mental Escapology, St. Moritz, Switzerland (2021); Cherry Blossoms,

Fondation Cartier, Paris (2021); and Archaeology Now, Galleria Borghese, Rome (2021). Hirst received the Turner Prize in 1995.

HENI works with world-leading artists and estates across various sectors including print-making, releases of original artworks, book publishing, films, exhibitions, news and research. Our mission is to make art accessible to everyone by giving people the chance to

learn about and collect art. HENI Primary enables artists to release original works of art on a dedicated digital platform, bringing the traditional fine-art experience online. The platform focuses on the primary sale of

original artworks, which have traditionally been handled exclusively by galleries and directly by artists’ studios.

www.heni.com

Phillips is where the world’s curious and bold connect with the art,

design, and luxury that inspires them. As a leading global platform for buying and selling 20th and 21st century works, Phillips offers dedicated expertise in the areas of Modern and Contemporary Art, Design, Photographs, Editions, Watches, and Jewels. Auctions and

exhibitions are primarily held in New York, London, Geneva, and Hong Kong, with representative offices based throughout Europe, the United States, and Asia. Phillips offers a regular selection of live and online auctions, along with items available for immediate purchase. Phillips also offers a range of services and advice on all

aspects of collecting, including private sales and assistance with appraisals, valuations, and financial planning. In addition to

providing selling and buying opportunities through auction, Phillips is committed to supporting contemporary arts and culture through a worldwide programme of Arts Partnerships.

www.phillips.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

www.heni.com

Phillips is where the world’s curious and bold connect with the art, design, and luxury that inspires them. As a leading global platform for buying and selling 20th and 21st century works, Phillips offers dedicated expertise in the areas of Modern and Contemporary Art, Design, Photographs, Editions, Watches, and Jewels. Auctions and exhibitions are primarily held in New York, London, Geneva, and Hong Kong, with representative offices based throughout Europe, the United States, and Asia. Phillips offers a regular selection of live and online auctions, along with items available for immediate purchase. Phillips also offers a range of services and advice on all aspects of collecting, including private sales and assistance with appraisals, valuations, and financial planning. In addition to providing selling and buying opportunities through auction, Phillips is committed to supporting contemporary arts and culture through a worldwide programme of Arts Partnerships.

www.phillips.com

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist, and educator interested in cities, architecture, and culture. He has written for the RIBA Journal, the Journal of Civic Architecture, Quietus, The Wire, the Guardian, and Icon. He teaches history and theory at UCL Bartlett and Greenwich University, and is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

visit

Damien Hirst, The Civilisation Paintings, is showing at Phillips, London, until 02 September.

Further details available at: www.exhibitions.phillips.com/collections/the-civilisation-paintings

images

figs.i,ii,vii,xx,xxii,xxiii

Installation View: Damien Hirst, The

Civilisation Paintings at Phillips London, 2024.

Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates

Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science

Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024.

fig.iii Damien Hirst, Creating Civilisation (detail), 2024. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024.

fig.iv

Damien Hirst, The Power of Civilisation (detail), 2024. Photographed by Will Jennings.

fig.v Damien Hirst, The Civilisation Question (detail), 2024. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024.

fig.viii

Damien Hirst, Civilisation Uncovered (detail), 2024. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024

figs.ix-xiii Still images from “Damien Hirst is busy working on his Civilisation paintings in his studio. What are your thoughts?“ by Heni, on TikTok, published 25 June 2024. Available at: https://www.tiktok.com/@heni/video/7384387961074273568.

© Heni

Sed consequat ante eget magna rhoncus ultricies laoreet sit amet odio. © Lorem Ipsum

fig.xiv,xxi

Damien Hirst, Civilisation and Entropy (detail), 2024. Photographed by Will Jennings.

fig.xv Damien Hirst, The Fall of Civilisation (detail), 2024. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024

fig.xvi Damien Hirst, Harmonious Civilisation (detail), 2024. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024.

fig.xvii,xviii

Damien Hirst, The Nature of Civilisation (detail), 2024. Photographed by Will Jennings.

fig.xix

Damien Hirst, Civilisation Circus (detail), 2024. Photographed by Will Jennings.

fig.xxiv Damien Hirst, Lost Civilisation, 2024. Oil on canvas.

78 x 60 in (198 x 152 cm).

Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024

fig.xxv Damien Hirst, Harmonious Civilisation, 2024.

Oil on canvas

78 x 60 in (198 x 152 cm). Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024.

fig.xxvi Damien Hirst, Civilisation Uncovered, 2024. Oil on canvas.

78 x 60 in (198 x 152 cm).

Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024

fig.xxvii Damien Hirst, Creating Civilisation, 2024.

Oil on canvas. 108 x 84 in (274 x 213 cm). Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024

fig.xxviii Damien Hirst, Concrete Civilisation, 2024.

Oil on canvas.

78 x 60 in (198 x 152 cm). Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024

fig.xxix Damien Hirst in the studio, 2024. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024

publication date

20 August 2022

tags

AI, Angkor Wat, Apollo, Blossom, Cities, Civilisation, Daily Mail, Dystopia, Flora, Flowers, James Fox, Frieze London, Furlough, Grey goo, Will Jennings, Jonathan Jones, Heni, Damien Hirst, Labour, Matthew Lloyd-Roberts, Nature, Painting, Phillips, Robots, Norman Rosenthal, Technology, TikTok, Toddington Manor, Utopia

Further details available at: www.exhibitions.phillips.com/collections/the-civilisation-paintings