The message is the bottle: Claes Oldenburg & Coosje van

Bruggen in Middlesbrough

In the public square outside the Middlesbrough Institute of

Modern Art – MIMA – is an unexpected sculpture of a seemingly-hollow, oversized,

leaning bottle. It is a work by celebrated artist couple Claes Oldenburg &

Coosje van Bruggen, constructed in 1993 & the only public sculpture by the

artists in the UK. Steve Taylor visited the gallery to see an exhibition

looking at the history, meaning & legacy of the project.

The Wikipedia entry for the public art produced by

the husband-and-wife team of Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen lists some

forty-six works, almost all of them gigantic replicas of everyday objects made

in durable industrial materials, beautifully painted or otherwise coloured, and

placed outdoors in site-specific locations; the artists referred to them as

their “large scale projects”. Some are situated in the public spaces of world

cities such as Los Angeles, Barcelona, Tokyo, Paris, and Seoul; others sit in

the grounds of art or design

institutions in Kassel, Bilbao, or Weil am Rhein. And then there’s the one in

Middlesbrough.

![]()

At the heart of this smallish not-quite-yet-post-industrial north eastern English port town is Centre Square, within which sits Bottle of Notes, an outlier in the duo’s oeuvre not only in its location but also in form – a 22m high skeletal outline of the object, the only solid part being the cap. Centre Square occupies a sizeable break in Middlesbrough’s gridded street plan. It is broadly open, enclosing green spaces and an artificial lake, and surrounded by buildings in a mish-mash of styles – late Victorian Gothic, civic PoMo, 1970s local government Brutalism – which give the appearance of having been carefully placed side-by-side like Lego pieces or Monopoly houses by a giant. It’s an apt comparison; Jonathan Swift’s subversive, surreal play on size and scale in Travels in Remote Nations of the World by Lemuel Gulliver was, according to Richard Cork[1], a longstanding “talisman” to Oldenburg.

Bottle of Notes sits close to one corner of the Teesside Combined Court Centre with its PoMo porticos and striped brick, leaning into the wind whipping through its twin layers of painted steel script, large scale renderings of Oldenburg’s (outer) and van Bruggen’s (inner) handwriting. The latter’s text is taken from one of her poems and reads “I like to remember seagulls in full flight gliding over the ring of canals”. The outer layer’s words are taken from the journals of the explorer James Cook, who was born near Middlesbrough in 1728 in what was then an outlying village. The wider area around the town is dotted with monuments to him. Cook’s text within the sculpture describes how “we had every advantage we could desire in observing the whole of the passage of planet Venus over the Sun’s disc”, a felicitous description of an eclipse, a phenomenon echoed metaphorically in Bottle of Notes’ overlapping forms.

![]()

The legend of Cook, complicated now with the recognition of his colonialist legacy, has long haunted Middlesbrough and informed the early gestation of the imagined object via sketches of shipwrecks, a phantasmic vision of Britain as a floating island, to the point where a message-in-a-bottle became the prospective work’s dominant trope by way of van Bruggen’s deep admiration for the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. In its eventually realised iteration, the message becomes the bottle, both parts intertwined physically – and metaphorically – in the makeup of the artwork.

The current show at MIMA – Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art – traces the development of Bottle of Notes through archive materials, maquettes, and video interviews with some of the key local actors involved in its original funding and placement. These exhibits are woven throughout the exhibition into a dialogue with pieces from MIMA’s permanent collection and others specially commissioned from artists Webb-Ellis, Nell Catchpole with Rachel Deakin, and Sam Venables, each of whom responds to “themes of place and identity” alongside local collaborations in a rich range of forms, including photography, sound art, installation and – appropriately – soft sculpture.

![]()

![]()

On the evidence of my visit, MIMA seems to have an admirably open relationship with surrounding communities: the reception area teemed with excitable primary school groups and a clutch of adults being shown around the gallery spontaneously broke into collective song (and nobody batted an eyelid). The show performs an elegant balancing act between bringing to life the historical record of Bottle of Notes’ creation and installation, utilising it as a springboard for contemporary practice, and making the whole accessible in ways appropriate to a space that combines the roles of imaginative contemporary gallery and key cultural resource for a town undergoing reinvention.

Beyond the gallery, Bottle of Notes – despite its dematerialising perforations – owns the space around it; the eight tons of British Steel-donated mild steel of which it is composed giving it a substantial heft. Although the critic Richard Cork, in an impressively comprehensive essay[2] published in 1993, the same year the sculpture was installed, worked hard to link Bottle of Notes aesthetically to local visual references such as the shapes of the chemical plants that dominated the town, his argument now feels unconvincing. That’s no bad thing; the sculpture shrugs off the windy expanse of the surrounding Centre Square with a dismissive “meh”. It just is, standing its ground without needing the contemporary imprimaturs of placemaking or cultural regeneration. This seems like a good position to be in, when the town in which it sits is about to undergo several multimillion-pound development projects.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Between the arrival of Bottle of Notes and these latest, imminent urban transformations, Middlesbrough was gifted with Tenemos, two enormous steel rings with a steel net strung between them on the town’s docks, created by artist Anish Kapoor with structural engineer Cecil Balmond. An emblematic piece of early twenty-first century public art in all its flimsiness and pointlessness, it is, in the words of critic Jonathan Jones[3], “deeply uncool”. Change a couple of letters and Tenemos easily becomes Tenuous, something Bottle of Notes – at once airy and firmly rooted – definitively isn’t.

Instead, Bottle of Notes channels the intentionality evident in Oldenburg’s 1961 manifesto in which he wrote “I am for an art that embroils itself with everyday crap and still comes out on top.” What could be more quotidian than an empty bottle? The pristine appearance – the result of extensive research and experimentation, and meticulous production processes – of most of Oldenburg and van Bruggen’s large-scale projects belies their roots in American pop art, in the older historical contexts of Dadaism, Surrealism and Art Brut, and, not least, in the urban scavenging and bricolage that Oldenburg practiced when living on 107 East 2nd Street in New York’s East Village during the 1950s. Bottle of Notes is, to use an exhausted cliché, the exception that proves the rule: literally open, sketchy and tentative: a transitional, rather than concretised object, that still in 2025 manages to reflect the ongoing transitions of urban Middlesbrough, the north east of England, and an industrial past that is far from ready to be consigned to the past or to the cultural nostalgia of heritage.

![]()

fig.viii

[1] Richard Cork ‘Message in a Bottle’ in Claes Oldenburg Coosje van Bruggen: Large-Scale Projects Thames & Hudson, 1993.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Jonathan Jones ‘Anish Kapoor's Temenos sculpture shows how uncool Britain is’ The Guardian 10 June 2010.

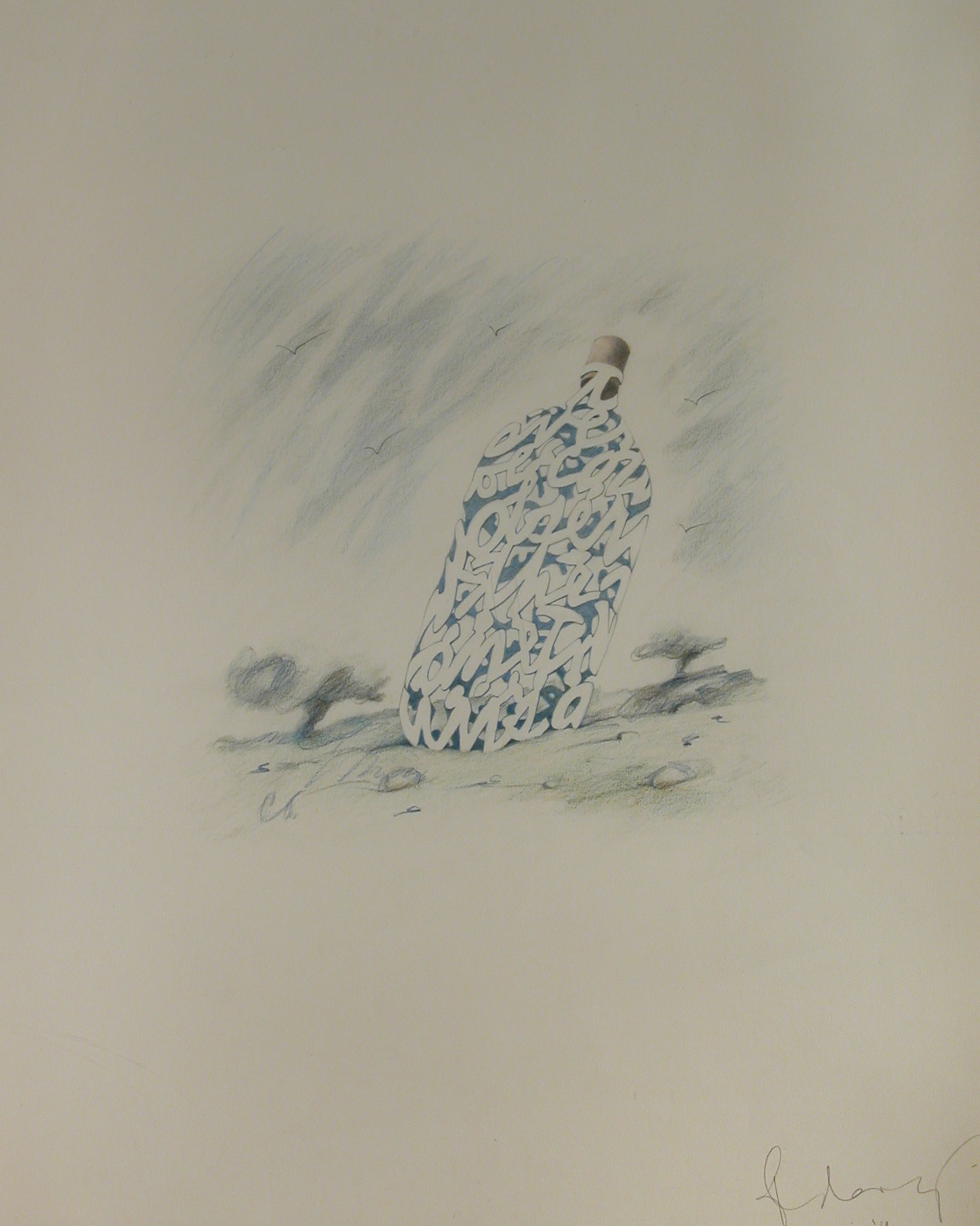

fig.i

At the heart of this smallish not-quite-yet-post-industrial north eastern English port town is Centre Square, within which sits Bottle of Notes, an outlier in the duo’s oeuvre not only in its location but also in form – a 22m high skeletal outline of the object, the only solid part being the cap. Centre Square occupies a sizeable break in Middlesbrough’s gridded street plan. It is broadly open, enclosing green spaces and an artificial lake, and surrounded by buildings in a mish-mash of styles – late Victorian Gothic, civic PoMo, 1970s local government Brutalism – which give the appearance of having been carefully placed side-by-side like Lego pieces or Monopoly houses by a giant. It’s an apt comparison; Jonathan Swift’s subversive, surreal play on size and scale in Travels in Remote Nations of the World by Lemuel Gulliver was, according to Richard Cork[1], a longstanding “talisman” to Oldenburg.

Bottle of Notes sits close to one corner of the Teesside Combined Court Centre with its PoMo porticos and striped brick, leaning into the wind whipping through its twin layers of painted steel script, large scale renderings of Oldenburg’s (outer) and van Bruggen’s (inner) handwriting. The latter’s text is taken from one of her poems and reads “I like to remember seagulls in full flight gliding over the ring of canals”. The outer layer’s words are taken from the journals of the explorer James Cook, who was born near Middlesbrough in 1728 in what was then an outlying village. The wider area around the town is dotted with monuments to him. Cook’s text within the sculpture describes how “we had every advantage we could desire in observing the whole of the passage of planet Venus over the Sun’s disc”, a felicitous description of an eclipse, a phenomenon echoed metaphorically in Bottle of Notes’ overlapping forms.

fig.ii

The legend of Cook, complicated now with the recognition of his colonialist legacy, has long haunted Middlesbrough and informed the early gestation of the imagined object via sketches of shipwrecks, a phantasmic vision of Britain as a floating island, to the point where a message-in-a-bottle became the prospective work’s dominant trope by way of van Bruggen’s deep admiration for the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. In its eventually realised iteration, the message becomes the bottle, both parts intertwined physically – and metaphorically – in the makeup of the artwork.

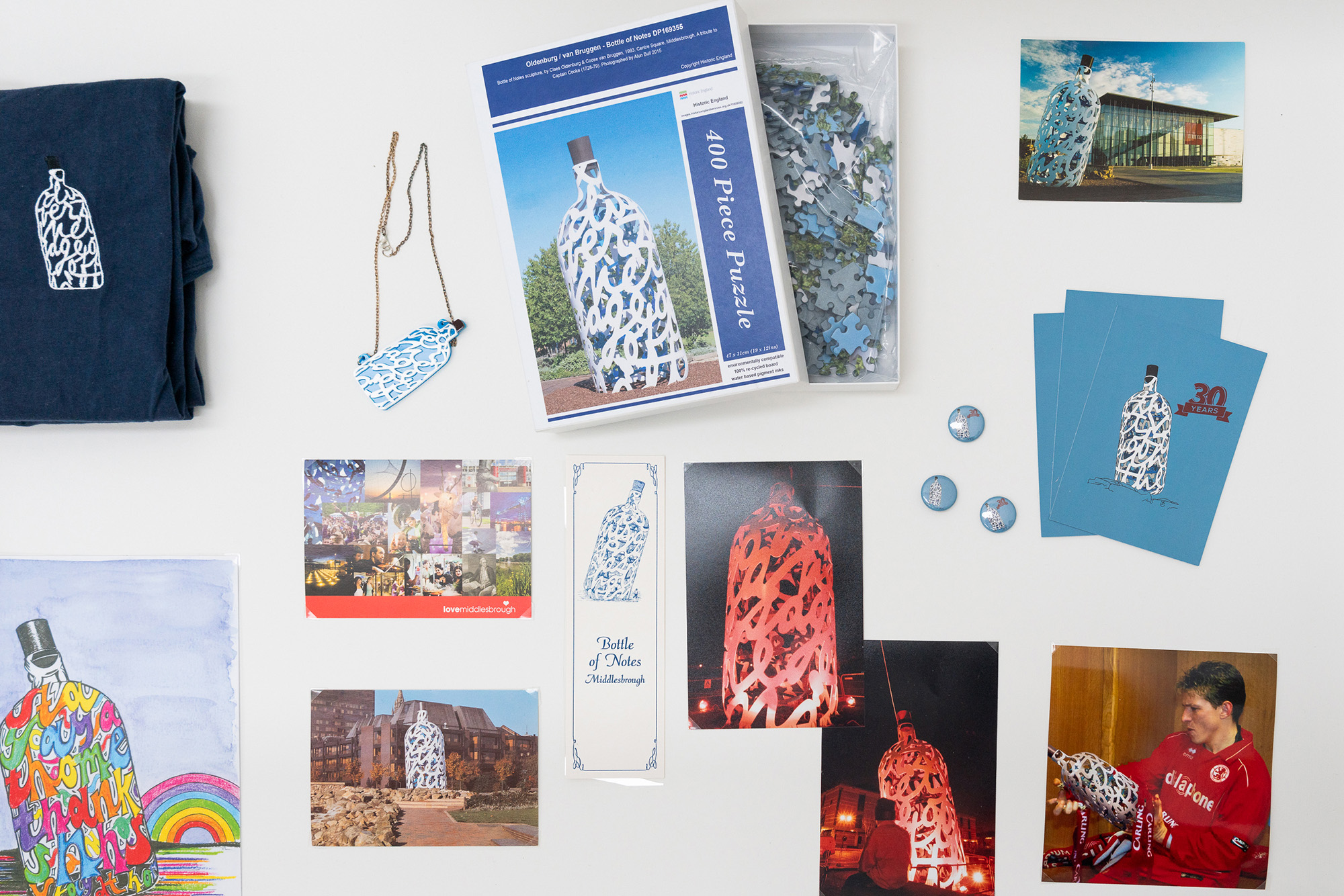

The current show at MIMA – Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art – traces the development of Bottle of Notes through archive materials, maquettes, and video interviews with some of the key local actors involved in its original funding and placement. These exhibits are woven throughout the exhibition into a dialogue with pieces from MIMA’s permanent collection and others specially commissioned from artists Webb-Ellis, Nell Catchpole with Rachel Deakin, and Sam Venables, each of whom responds to “themes of place and identity” alongside local collaborations in a rich range of forms, including photography, sound art, installation and – appropriately – soft sculpture.

figs.iii,iv

On the evidence of my visit, MIMA seems to have an admirably open relationship with surrounding communities: the reception area teemed with excitable primary school groups and a clutch of adults being shown around the gallery spontaneously broke into collective song (and nobody batted an eyelid). The show performs an elegant balancing act between bringing to life the historical record of Bottle of Notes’ creation and installation, utilising it as a springboard for contemporary practice, and making the whole accessible in ways appropriate to a space that combines the roles of imaginative contemporary gallery and key cultural resource for a town undergoing reinvention.

Beyond the gallery, Bottle of Notes – despite its dematerialising perforations – owns the space around it; the eight tons of British Steel-donated mild steel of which it is composed giving it a substantial heft. Although the critic Richard Cork, in an impressively comprehensive essay[2] published in 1993, the same year the sculpture was installed, worked hard to link Bottle of Notes aesthetically to local visual references such as the shapes of the chemical plants that dominated the town, his argument now feels unconvincing. That’s no bad thing; the sculpture shrugs off the windy expanse of the surrounding Centre Square with a dismissive “meh”. It just is, standing its ground without needing the contemporary imprimaturs of placemaking or cultural regeneration. This seems like a good position to be in, when the town in which it sits is about to undergo several multimillion-pound development projects.

figs.v-vii

Between the arrival of Bottle of Notes and these latest, imminent urban transformations, Middlesbrough was gifted with Tenemos, two enormous steel rings with a steel net strung between them on the town’s docks, created by artist Anish Kapoor with structural engineer Cecil Balmond. An emblematic piece of early twenty-first century public art in all its flimsiness and pointlessness, it is, in the words of critic Jonathan Jones[3], “deeply uncool”. Change a couple of letters and Tenemos easily becomes Tenuous, something Bottle of Notes – at once airy and firmly rooted – definitively isn’t.

Instead, Bottle of Notes channels the intentionality evident in Oldenburg’s 1961 manifesto in which he wrote “I am for an art that embroils itself with everyday crap and still comes out on top.” What could be more quotidian than an empty bottle? The pristine appearance – the result of extensive research and experimentation, and meticulous production processes – of most of Oldenburg and van Bruggen’s large-scale projects belies their roots in American pop art, in the older historical contexts of Dadaism, Surrealism and Art Brut, and, not least, in the urban scavenging and bricolage that Oldenburg practiced when living on 107 East 2nd Street in New York’s East Village during the 1950s. Bottle of Notes is, to use an exhausted cliché, the exception that proves the rule: literally open, sketchy and tentative: a transitional, rather than concretised object, that still in 2025 manages to reflect the ongoing transitions of urban Middlesbrough, the north east of England, and an industrial past that is far from ready to be consigned to the past or to the cultural nostalgia of heritage.

fig.viii

[1] Richard Cork ‘Message in a Bottle’ in Claes Oldenburg Coosje van Bruggen: Large-Scale Projects Thames & Hudson, 1993.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Jonathan Jones ‘Anish Kapoor's Temenos sculpture shows how uncool Britain is’ The Guardian 10 June 2010.

Coosje van Bruggen (b. 1942, Groningen, d. 2009, Los Angeles) was a sculptor, art historian, and critic who collaborated extensively with her husband, the artist Claes Oldenburg. Throughout her career, van Bruggen held positions at various institutions including the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam; Sonsbeek 71, Artforum; and the Yale University School of Art. She also authored numerous art historical books. Van Bruggen’s first collaboration with Oldenburg was in 1976, when Trowel I, originally shown at Sonsbeek 71, was rebuilt and relocated to the sculpture garden of the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands. In 1978, van Bruggen moved to New York, where she continued to work with Oldenburg. Together, the pair executed more than forty large-scale projects, which have been sited in urban surroundings in Europe, Asia, and the U.S.A.

Claes Oldenburg (b. 1929, Stockholm, d. 2022, New York) moved to New York City in 1956, where he established himself as a pivotal figure in American art. Oldenburg’s initial interest in Happenings, performance art, and installation – including such seminal works as The Street (1960) and The Store (1961) – soon evolved into a concentration on single sculptures. Working with ordinary, everyday objects, he went on to develop “soft” sculpture and fantastic proposals for civic monuments. In 1969, Oldenburg took up fabrication on a large scale with Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks installed on the Yale University campus. From 1976 until 2009 he

worked in partnership with his wife, Coosje van Bruggen, executing countless large-scale projects for various public settings around the world. Oldenburg was honoured with a one-person exhibition of his work at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1969, and with a retrospective organised by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 1995. His work is represented in collections including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art; and the Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Steve Taylor writes about cities, music, arts & culture; features, essays & profiles for print and online magazines. He researches & reports on urban trends for businesses, including architecture firms & design studios. He mentors MA students in the creative arts, alongside researching a PhD on music & urban space.

www.studiostevetaylor.com

worked in partnership with his wife, Coosje van Bruggen, executing countless large-scale projects for various public settings around the world. Oldenburg was honoured with a one-person exhibition of his work at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1969, and with a retrospective organised by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 1995. His work is represented in collections including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art; and the Centre Pompidou, Paris.