Folkestone Triennial looks deep in time, land & sea for its latest

edition

Folkestone, on the Kent coast, is a town packed with contemporary

artworks left in situ from the past five editions of the Folkestone Triennial.

Now, the 6th edition curated by Sorcha Carey is open & 18 more

artists have added to the exciting cultural offer, all themed around land,

geology & ancient time. We visit to find our highlights including Laure

Prouvost, Cooking Section & Emilija Škarnulytė.

Most biennials and triennials pop up and disappear, often a

fabulous explosion of culture for those who attend the galleries or warehouses

it may be based in, but leaving no trace other than archive images and memory

after the works are packed and shipped off. Folkestone Triennial is a bit

different, scattering its works across often unexpected corners of the seaside

town, with many of them remaining in place after the event officially closes

and starts preparing for its next iteration.

Consequently, Folkestone has become a town saturated with contemporary art unlike any other town or city in the world. Over a short walk, visitors may encounter works by Tracy Emin, Yoko Ono, Antony Gormley, Lubaina Himid, or Gilbert & George. It makes for a series of encounters that can either be sought out on routes around the town, or simply pieces that get noticed in passing, and sit in their in situ environment over years, perhaps slowly shifting meaning and becoming a part of the place.

Some of the works are not solely for decorative curiosity, but combine creativity with social infrastructure: Assemble created a skate park on the Harbour Arm, the extension of the railway that pushes into the sea, creating the fishing harbour; Diane Dever and The Decorators created an Urban Room for the community to discuss the past and future of Folkestone; muf Architecture/Art oversaw landscaping of sculpting of a now very well used greenspace; and Sol Calero’s 2017 brightly coloured pavilion offers shelter on the stony beach.

The 2025 edition is overseen by Alistair Upton, Chief Executive of Creative Folkestone – the organisation behind the Triennial as well as many other cultural developments in the town – and curator Sorcha Carey. The theme, How Lies the Land?, invited 18 artists or groups to consider the layers of history underneath and within the geography and geology of Folkestone. Here, we pick some of the highlights:

Consequently, Folkestone has become a town saturated with contemporary art unlike any other town or city in the world. Over a short walk, visitors may encounter works by Tracy Emin, Yoko Ono, Antony Gormley, Lubaina Himid, or Gilbert & George. It makes for a series of encounters that can either be sought out on routes around the town, or simply pieces that get noticed in passing, and sit in their in situ environment over years, perhaps slowly shifting meaning and becoming a part of the place.

Some of the works are not solely for decorative curiosity, but combine creativity with social infrastructure: Assemble created a skate park on the Harbour Arm, the extension of the railway that pushes into the sea, creating the fishing harbour; Diane Dever and The Decorators created an Urban Room for the community to discuss the past and future of Folkestone; muf Architecture/Art oversaw landscaping of sculpting of a now very well used greenspace; and Sol Calero’s 2017 brightly coloured pavilion offers shelter on the stony beach.

The 2025 edition is overseen by Alistair Upton, Chief Executive of Creative Folkestone – the organisation behind the Triennial as well as many other cultural developments in the town – and curator Sorcha Carey. The theme, How Lies the Land?, invited 18 artists or groups to consider the layers of history underneath and within the geography and geology of Folkestone. Here, we pick some of the highlights:

Laure Prouvost

Above Frontiers, Oui Connect

Standing proudly on two concrete pedestals once used for mooring ships, a mythical bird is captured in motion. It is formed of terrazzo – made with stone, glass, shells, marble, and minerals – with pointed glass beaks. Whether the creature, like Cerberus, has three heads, or these are simply three frames of an Eadweard Muybridge-esque animation of a bird screaming into the sky, is up to interpretation.

On the adjoining plinth is a smaller (one-headed) child bird. Prouvost’s work frequently speaks to ideas of motherhood and maternal knowledge, invoking both her own female relatives as well as imagined and folkloric feminine figures in her videos and installation set pieces. Here, it is richly celebrated – the mother bird perhaps shouting in protective defence of her child, or in a motion of movement towards the child perhaps in an act of care or feeding.

Above Frontiers, Oui Connect

Standing proudly on two concrete pedestals once used for mooring ships, a mythical bird is captured in motion. It is formed of terrazzo – made with stone, glass, shells, marble, and minerals – with pointed glass beaks. Whether the creature, like Cerberus, has three heads, or these are simply three frames of an Eadweard Muybridge-esque animation of a bird screaming into the sky, is up to interpretation.

On the adjoining plinth is a smaller (one-headed) child bird. Prouvost’s work frequently speaks to ideas of motherhood and maternal knowledge, invoking both her own female relatives as well as imagined and folkloric feminine figures in her videos and installation set pieces. Here, it is richly celebrated – the mother bird perhaps shouting in protective defence of her child, or in a motion of movement towards the child perhaps in an act of care or feeding.

The whole thing, however, stays far from didactic and remains in the

artist’s regular realm of unusual, magical otherness. A plug dangling from the

tale of the larger creature calls questions of reality and this natural scene –

there seems to be a hope for a kind of connection, perhaps between observing

humans and rendered nature, or between the many-headed creature and the sea

that at high tide will raise to nearly touch the hanging plug. Or, perhaps it

forms connection across the sea to other Prouvost creatures in Dunkirk and De

Panne.

When Folkestone Triennial’s work are unleashed into the town, it is not known which will remain in situ after the festival concludes. In part, that is down to material form, but also down to whether the public accept and adopt the work and wish it to become part of the urban fabric. It would be a surprise if Prouvost’s three-headed bird doesn’t quickly become a friend to Folkestone and part of a future mythology of place, in the same way that Cornelia Parker’s sea-gazing mermaid from 2011 is now a part of the community.

When Folkestone Triennial’s work are unleashed into the town, it is not known which will remain in situ after the festival concludes. In part, that is down to material form, but also down to whether the public accept and adopt the work and wish it to become part of the urban fabric. It would be a surprise if Prouvost’s three-headed bird doesn’t quickly become a friend to Folkestone and part of a future mythology of place, in the same way that Cornelia Parker’s sea-gazing mermaid from 2011 is now a part of the community.

Dorothy Cross

Red Erratic

A little further up Folkestone’s Harbour arm from Laure Prouvost’s towering bird is a sculpture no less monumental, but carrying a quietness and sense of sorrow. Located at a lower level accessible from steps, a level that sits at water’s edge at low tide and gets completely flooded at high, a heavy lump of Syrian Damascus Rose marble sits as if washed up by the waves.

The work speaks to ongoing human migration as a result from the ongoing Syrian war, with many of those impacted making the dangerous crossing across the channel before arriving on beaches along this stretch of the Kent coast. Feet are carved into the rough, top surface of the marble lump, speaking to the humanity of this movement as well as the journey and transformation of St Paul along the road to Damascus.

Red Erratic

A little further up Folkestone’s Harbour arm from Laure Prouvost’s towering bird is a sculpture no less monumental, but carrying a quietness and sense of sorrow. Located at a lower level accessible from steps, a level that sits at water’s edge at low tide and gets completely flooded at high, a heavy lump of Syrian Damascus Rose marble sits as if washed up by the waves.

The work speaks to ongoing human migration as a result from the ongoing Syrian war, with many of those impacted making the dangerous crossing across the channel before arriving on beaches along this stretch of the Kent coast. Feet are carved into the rough, top surface of the marble lump, speaking to the humanity of this movement as well as the journey and transformation of St Paul along the road to Damascus.

In a neighbouring sunken level, a single figure by Antony Gormley stands

looking out to sea, and is smothered by it as the tides rise. Dorothy Cross’

work acts as a counterpoint – where Gormley’s might speak to the imaginary

human and its relationship to time passing, Cross’s marble form speaks to

specific people at a time of crises and reminds us that it can be helpful for thought

and art to not solely remain in the abstract but directly speak to active

situations.

Marble is often hewn into heroic form. Here, however, it is left semi natural, polished to the sides but with imperfection and with a coarse top that will age and evolve as the sea determines. Indeed, the presence of cut-off feet atop the block suggest a notional pedestal of a grand statue, as the delicately poised ankles of David support such a powerful figure above. But here the figures are severed, the people it represents – in the work and indeed in our cultural reporting of those fleeing Syria across the English Channel – anonymised and without identity.

Marble is often hewn into heroic form. Here, however, it is left semi natural, polished to the sides but with imperfection and with a coarse top that will age and evolve as the sea determines. Indeed, the presence of cut-off feet atop the block suggest a notional pedestal of a grand statue, as the delicately poised ankles of David support such a powerful figure above. But here the figures are severed, the people it represents – in the work and indeed in our cultural reporting of those fleeing Syria across the English Channel – anonymised and without identity.

Cooking Sections

Ministry of Sewers

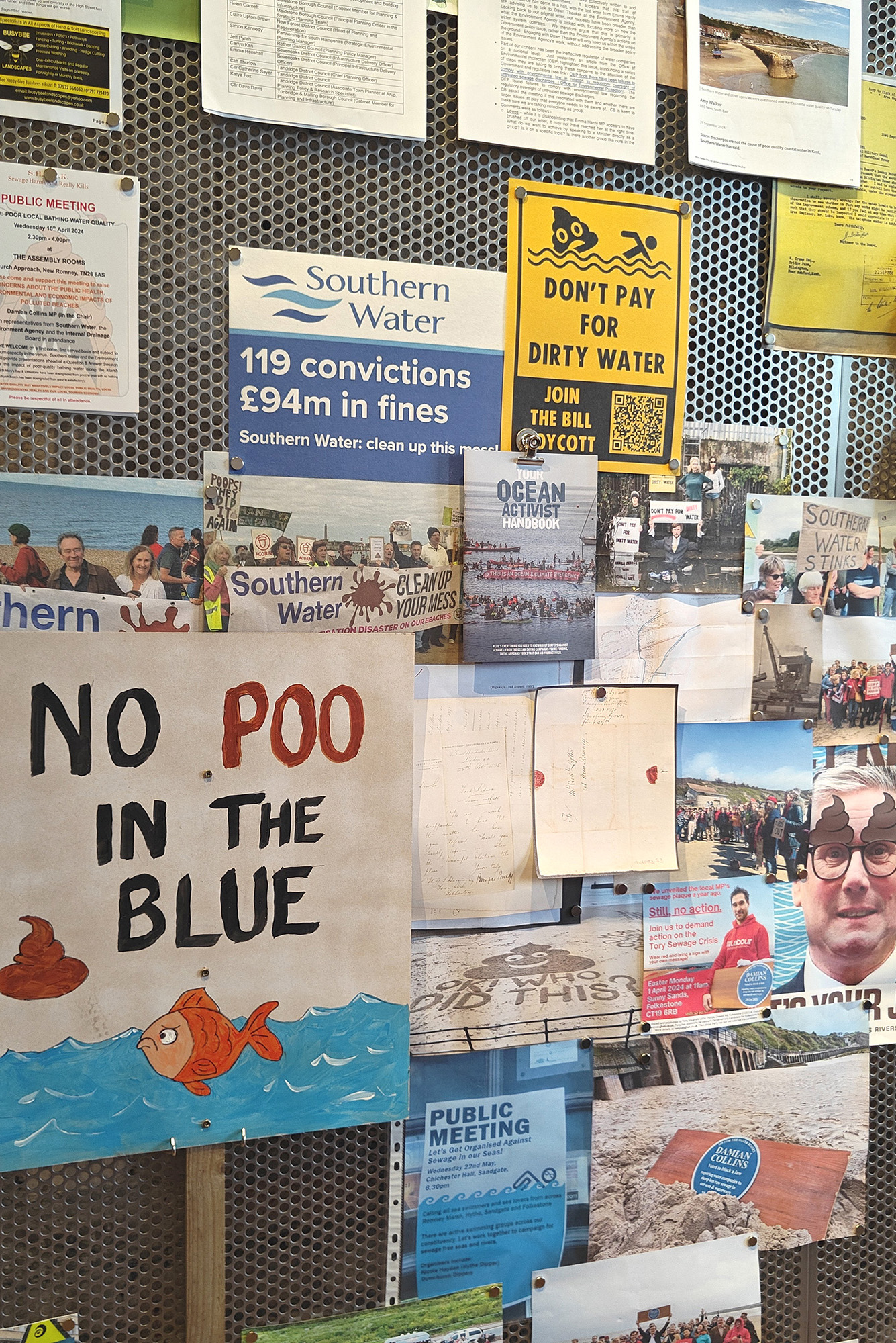

Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe, both Readers in Architecture and Spatial Practice at the RCA, created Cooking Sections in 2013 to look at the intersection of food with landscape, economies, people, and architecture – here, however, they are considering food in its post-digested form once it’s found its way into the subterranea.

They have created a new governmental body, the Ministry of Sewers, to raise questions and inter-community awareness around the increasing issue of pollution in our seas, acting as a repository and archive of activism, legal matters, and news coverage going back to Margaret Thatcher’s decision to privatise the sewer network, but also acting as a living space for reporting of issues and potential legal action.

Ministry of Sewers

Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe, both Readers in Architecture and Spatial Practice at the RCA, created Cooking Sections in 2013 to look at the intersection of food with landscape, economies, people, and architecture – here, however, they are considering food in its post-digested form once it’s found its way into the subterranea.

They have created a new governmental body, the Ministry of Sewers, to raise questions and inter-community awareness around the increasing issue of pollution in our seas, acting as a repository and archive of activism, legal matters, and news coverage going back to Margaret Thatcher’s decision to privatise the sewer network, but also acting as a living space for reporting of issues and potential legal action.

Slots throughout the day are available for the public to report

their experiences of encountering pollution, often through swimming in the sea

and resulting in rashes or other illnesses. The uniformed Ministers taking

these testimonies are not performers, but in fact members of various local pollution

activist groups, and one benefit Cooking Sections hope for is that the project

will built inter-organisational knowledge in groups that can be focused upon

one regional area or one specific localised issue.

The public can also register their stories through an online portal, with the potential that these testimonies don’t simply create a living archive but can offer information and data sets that could be mapped against certain times of the year, locations, or known sewage dumping, with the potential to support future legal action.

The public can also register their stories through an online portal, with the potential that these testimonies don’t simply create a living archive but can offer information and data sets that could be mapped against certain times of the year, locations, or known sewage dumping, with the potential to support future legal action.

Emilija Škarnulytė

Burial

Slightly along the coast from Folkestone is the immense presence of Dungeness Nuclear Power Station. Artist Emilija Škarnulytė alludes to it in her immersive video work exploring Ignalina power station in her country of Lithuania, the twin of Chernobyl and which is undergoing a slow dismantling by hand since 2004, a process intended to conclude when the site is returned in 2030. Škarnulytė spent seven years with recording elements of the power station and a nearby simulacra of the control panel room, as well as documenting the meticulous process of cutting and removing tiny elements of such a gargantuan piece of cursed architecture.

Sitting on the edge of the border with Belurus, it now also acts as an architectural memory of the nation’s Soviet history and nervous proximity to the current agitated Russian regime. In the beautifully shot film, a Burmese python entwines itself around control room apparatus and explores crevices. It speaks to threat and fear – both the political present and material legacy – but also a knowledge of deep future where the threat will never retreat, the ouroboros symbol of a serpent eating its own tail, fear and threat ever-repeating.

Burial

Slightly along the coast from Folkestone is the immense presence of Dungeness Nuclear Power Station. Artist Emilija Škarnulytė alludes to it in her immersive video work exploring Ignalina power station in her country of Lithuania, the twin of Chernobyl and which is undergoing a slow dismantling by hand since 2004, a process intended to conclude when the site is returned in 2030. Škarnulytė spent seven years with recording elements of the power station and a nearby simulacra of the control panel room, as well as documenting the meticulous process of cutting and removing tiny elements of such a gargantuan piece of cursed architecture.

Sitting on the edge of the border with Belurus, it now also acts as an architectural memory of the nation’s Soviet history and nervous proximity to the current agitated Russian regime. In the beautifully shot film, a Burmese python entwines itself around control room apparatus and explores crevices. It speaks to threat and fear – both the political present and material legacy – but also a knowledge of deep future where the threat will never retreat, the ouroboros symbol of a serpent eating its own tail, fear and threat ever-repeating.

Beyond a poetic study of place, Škarnulytė’s film explores the human

desire to bury the immortal, form Etruscan tombs to the most cutting edge experiments

in France for the contained burying of nuclear waste. This also speaks to how

we contend with memories as well as material – Lithuania being a country with rich

national, royal, and political histories that are slowly again being recognised,

reconsidered, and critically explored. Within the post-Soviet, EU-membership

period, culture and architecture has been an important element of considering a

national identity, a process that does not hide darker or less romantic moments

but understands them as part of an unfolding narrative.

The piece also speaks to Škarnulytė’s own biography – her grandmother was blinded by Chernobyl’s fallout in 1986, consequently never seeing her granddaughter born a year later. The film recognises a personal impact from such a global event and threat, but also through a work that requires concentrated looking, gives real care to photographic quality, composition, and the visual.

The piece also speaks to Škarnulytė’s own biography – her grandmother was blinded by Chernobyl’s fallout in 1986, consequently never seeing her granddaughter born a year later. The film recognises a personal impact from such a global event and threat, but also through a work that requires concentrated looking, gives real care to photographic quality, composition, and the visual.

Katie Paterson

Afterlife

In a work that took years to make, but carries within stories of much longer, deeper histories, Katie Paterson presents a circular table with soft, sunken pockets holding 197 individual tiny amulets. Each talisman is of a different form, coming from a variety of historic civlisations: Islamic, Viking, Celtic, Pre-Colombian, Egyptian, and more. They were all selected from international museum archives, with the artist using digital 3D scans in her process to recreate the objects into an archive that delicately fills one of Folkestone’s Martello Towers.

There is another layer to the work, however. Each amulet is made of a material representing a pressing environmental issue of our time. Whereas the original items may be carved of wood, ivory, or marble, here Paterson has used compressed circuit boards, microplastics, sulphide mining residue, or lithium from the Atacama Desert – one item is even made from an entire polystyrene cup discovered at the deepest part of the Ocean, 11,000m at the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

Afterlife

In a work that took years to make, but carries within stories of much longer, deeper histories, Katie Paterson presents a circular table with soft, sunken pockets holding 197 individual tiny amulets. Each talisman is of a different form, coming from a variety of historic civlisations: Islamic, Viking, Celtic, Pre-Colombian, Egyptian, and more. They were all selected from international museum archives, with the artist using digital 3D scans in her process to recreate the objects into an archive that delicately fills one of Folkestone’s Martello Towers.

There is another layer to the work, however. Each amulet is made of a material representing a pressing environmental issue of our time. Whereas the original items may be carved of wood, ivory, or marble, here Paterson has used compressed circuit boards, microplastics, sulphide mining residue, or lithium from the Atacama Desert – one item is even made from an entire polystyrene cup discovered at the deepest part of the Ocean, 11,000m at the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

Whereas in a museum such items may be categorised chronologically,

from oldest to youngest, here the 197 items are arranged according to themes including

Extraction, Mining, War, Pollution, and Wildfire. This creates a flattening of

history into one before and after the Anthropocene, and a useful tool to deromanticise

our position from one at the pinnacle of civilisational history to the era that

has the potential to destroy everything that has gone before.

The objects take various forms from animals and gods to maps of the solar system and bodily parts, speaking to the wealth and variety of human existence, and how it is married to hope for the future. While the presentation is poetic, soft, and beautiful, it portrays a violent reality and acts as a call to action.

The objects take various forms from animals and gods to maps of the solar system and bodily parts, speaking to the wealth and variety of human existence, and how it is married to hope for the future. While the presentation is poetic, soft, and beautiful, it portrays a violent reality and acts as a call to action.

Monster Chetwynd

Salamander Playground

Adding to the list of previous Triennial artists, above, who have created works that don’t only add to an artistic canon, but also support the infrastructure of Folkestone, Monster Chetwynd will be creating a creature-infused, imagination-fuelling playground. Inspired by a visit to the site, the close-yet-distant presence of Europe across the water, as well as fantastical creatures from Lewis Carroll and Bryan Talbot’s Grandville comics featuring anthropomorphic animals.

The only creature to have so far emerged from the imaginary into reality is a salamander on its hind legs, arms outrstretched at the top of Payers Park. Children can pose with, hug, or play with the creature that Chetwynd speaks of as being ancient and having self-regenerating abilities, but soon there’ll be a whole realm of animals intermingling with a play equipment forming a central part of a regenerated Bouverie Square adjoining the town’s main bus station.

Salamander Playground

Adding to the list of previous Triennial artists, above, who have created works that don’t only add to an artistic canon, but also support the infrastructure of Folkestone, Monster Chetwynd will be creating a creature-infused, imagination-fuelling playground. Inspired by a visit to the site, the close-yet-distant presence of Europe across the water, as well as fantastical creatures from Lewis Carroll and Bryan Talbot’s Grandville comics featuring anthropomorphic animals.

The only creature to have so far emerged from the imaginary into reality is a salamander on its hind legs, arms outrstretched at the top of Payers Park. Children can pose with, hug, or play with the creature that Chetwynd speaks of as being ancient and having self-regenerating abilities, but soon there’ll be a whole realm of animals intermingling with a play equipment forming a central part of a regenerated Bouverie Square adjoining the town’s main bus station.

J Maizlish Mole

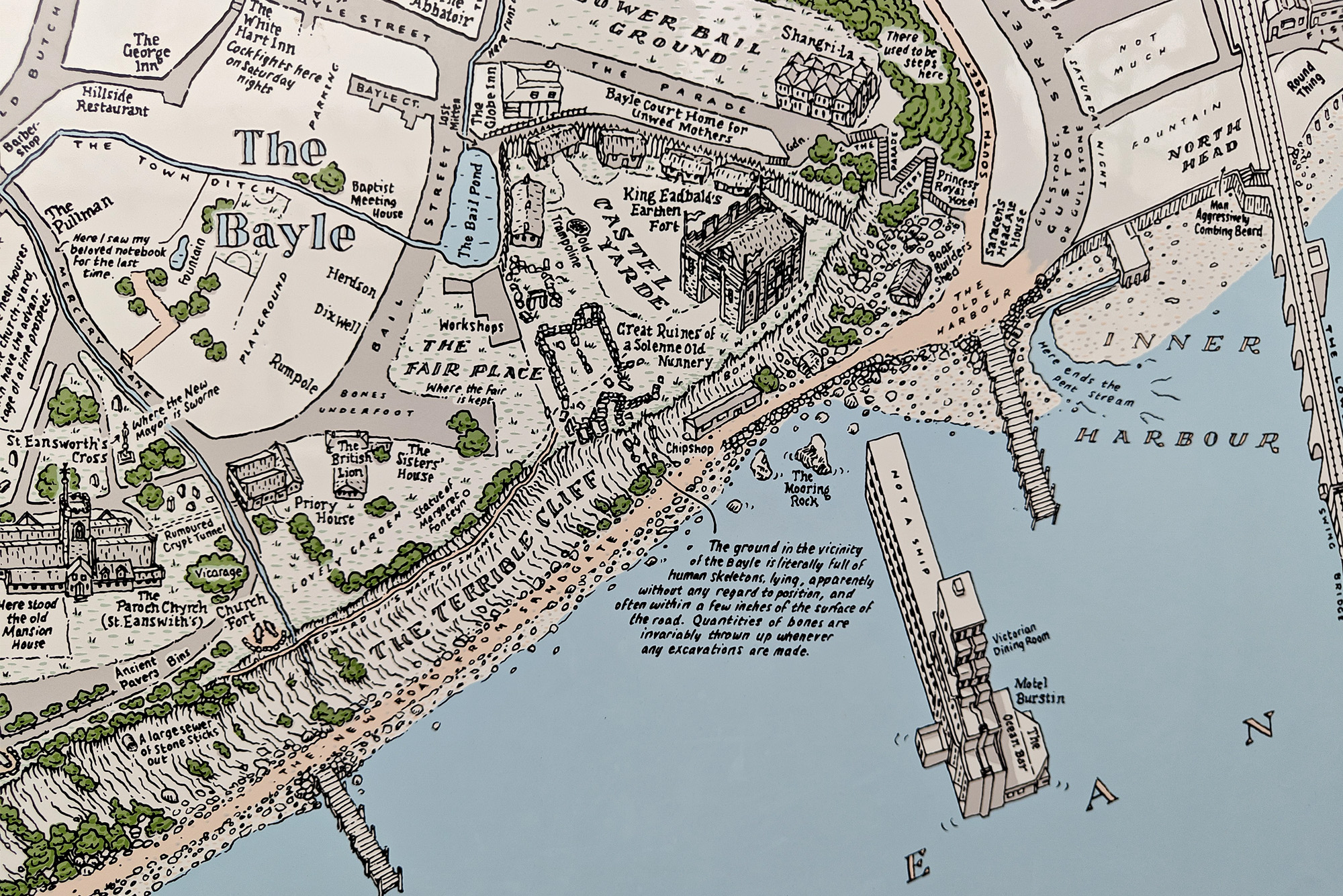

Folkestone in Ruins

What the artist describes as an “upside-down archaeology” is present in a richly detailed, hand-drawn map present in a number of Folkestone locations. Blown up large and mounted on urban infrastructural style metal information boards, the maps don’t so much help the public around the town but allow them to go deeper in land and time.

It’s all pulled together through walking around the area over 31 days and reading a range of texts that speak to the history of the town. All the garnered information was compiled into a database of 120 objects, observations, or historical observations, many of which are then incorporated into an intricately drawn map that reveals more and more details, and dry humour, the deeper it is looked into.

It is a palimpsest of countless histories, from an incomplete Napoleonic redoubt to the UK Boarder Control centre, from a pile of Saxon skulls under a church to the “Huge Tesco”, and from the pub where Saturday night cockfights took place to the site of a Jimi Hendrix gig on new year’s Eve 1966. Altogether, it’s a wonderful lateral exploration of place that, unlike most maps, doesn’t set out to offer clarity of direction or place, but to celebrate a muddled, confused, and playful history.

Folkestone in Ruins

What the artist describes as an “upside-down archaeology” is present in a richly detailed, hand-drawn map present in a number of Folkestone locations. Blown up large and mounted on urban infrastructural style metal information boards, the maps don’t so much help the public around the town but allow them to go deeper in land and time.

It’s all pulled together through walking around the area over 31 days and reading a range of texts that speak to the history of the town. All the garnered information was compiled into a database of 120 objects, observations, or historical observations, many of which are then incorporated into an intricately drawn map that reveals more and more details, and dry humour, the deeper it is looked into.

It is a palimpsest of countless histories, from an incomplete Napoleonic redoubt to the UK Boarder Control centre, from a pile of Saxon skulls under a church to the “Huge Tesco”, and from the pub where Saturday night cockfights took place to the site of a Jimi Hendrix gig on new year’s Eve 1966. Altogether, it’s a wonderful lateral exploration of place that, unlike most maps, doesn’t set out to offer clarity of direction or place, but to celebrate a muddled, confused, and playful history.

And more...

Folkestone Triennial 2025 also features works from Jennifer Tee, john gerrard, Hanna Tuulikki, Emeka Ogboh, Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape, Céline Condorelli, Prabhakar Pachpute, Rae-Yen Song 宋瑞渊, Rubiane Maia, Sara Trillo, and Sarah Wood.

Folkestone Triennial 2025 also features works from Jennifer Tee, john gerrard, Hanna Tuulikki, Emeka Ogboh, Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape, Céline Condorelli, Prabhakar Pachpute, Rae-Yen Song 宋瑞渊, Rubiane Maia, Sara Trillo, and Sarah Wood.