Cerith Wyn Evans glows in MAAT, Lisbon

Cerith Wyn Evans has quietly become one of the most

important British artists, quietly working his practice across film and sculpture

since the 1980s while YBA artists and louder voices took centre stage. Over

that time, however, he has been picking up important shows and awards, including

the 2017 Tate Britain Commission for which he created an enormous vortex of white

neon light. That work has now been installed in the Amanda Levete-designed MAAT in Lisbon, so Will

Jennings went to see it and other works in the solo presentation.

Some exhibitions seem like they can be picked up and placed

into any modern art gallery and have the same impact as anywhere else. The

concept of the white cube space is, after all, one of abstracted uniformity,

where character, context, and any depth beneath the meticulous surfaces is

hidden so as to not distract from the singular message of the inhabitant

artworks.

Sometimes, artists or exhibitions seem perfectly paired for a space, and the meaning of both art objects on display and the surrounding architecture marries. This often happens within an historic or classical setting, where messages of new works juxtapose or mingle with an historic narrative, but at MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology alongside the River Tigus outside the centre of Lisbon a thoroughly contemporary space makes the perfect setting for a solo exhibition by Welsh artist Cerith Wyn Evans.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Wyn Evans’ most well-known works entangle neon, electricity, and light into sculptural forms that flicker and shimmer bright whiteness. The host venue, MAAT, is owned and operated by EDP, a Portuguese electrical utilities company, and is formed of two impressive pieces of architecture: the red brick 1908 Tejo Power Station and adjoining Gallery building designed by Amanda Levete, founder of London-based AL_A architecture studio, within which Wyn Evans’ works throb.

Externally, Levete’s MAAT Gallery building, now a decade old, is already a foundational part of Lisbon’s cultural and touristic boom. White ceramic surfaces seem to peel from ground level to reveal entrances and openings which let both people and natural light into the entombed gallery spaces. The void between overhang and riverside promenade has become one of the city’s most Instagrammable moments, while the roof offers visual access to a wide vista and a bridge across railway lines to the residential parts of Belém.

![]()

![]()

Inside, the architecture is dominated by a central void, a parametricised Guggenheim ramp with a gentle Baroque curve wrapping around the main central gallery space. Other, less successful (from a visitor and curatorial standpoint) lead off this central void, but the visitor sequence that folds from outside to inside to curled entombing void is one that few international museums can rival.

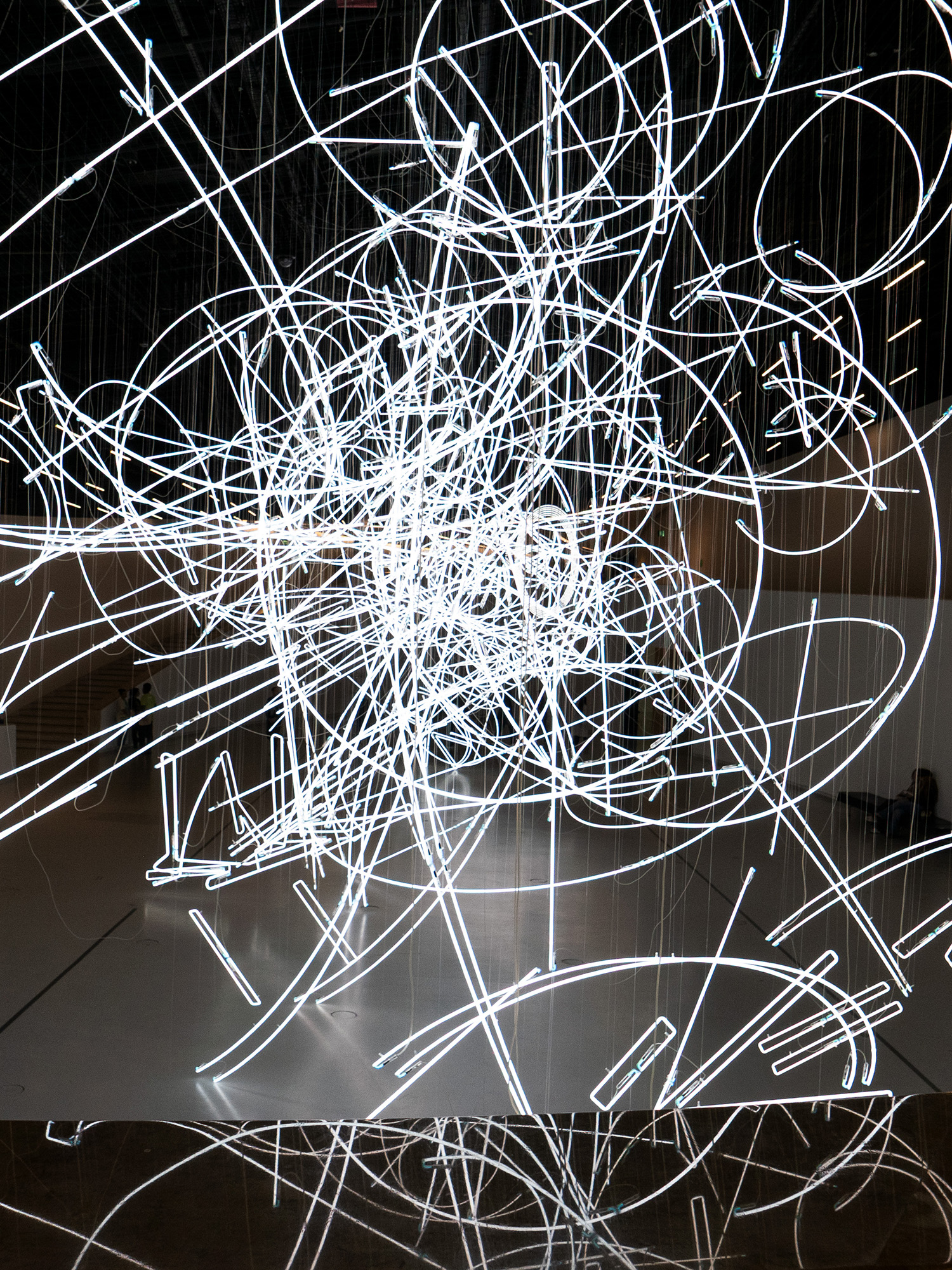

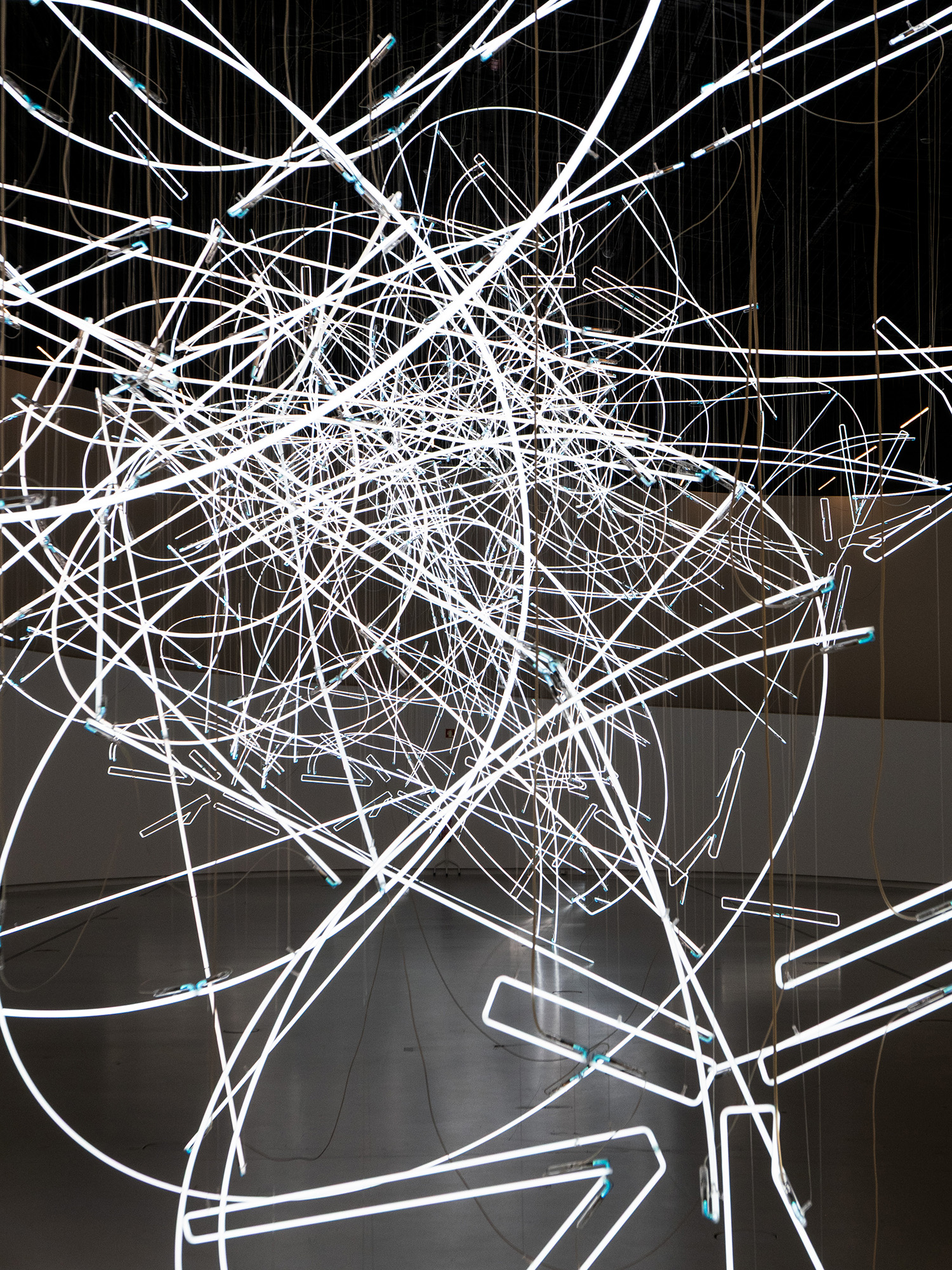

It also makes a perfect ready-made setting for Wyn Evans’ Forms in Space… by Light (in Time) (2017), an enormous entanglement of pure white light seemingly stuck in mid-explosion, comprising nearly 2km of neon. Upon entry it is arresting, and invites pause as if to capture scale, complexity, and even logistics. But as soon as some sense of it has been gained, and the visitor moves onwards along the curved ramp, it immediately transforms. Almost impossible to read, any movement around or under its interlocking arrangements completely changes its form, swooshes and lines that seemed conjoined quickly separate to show themselves as distant relatives, moments of perfect geometry twist away to reveal as sinuous, unexpected lines.

![]()

![]()

![]()

That it is entirely constructed of electricity is present not only in the soft flicker and gentle hum of transformers, but also in the fact that the building itself is so rooted in the heritage of power. The former power station next door is now a labyrinth of heritage industrial assets which emerge into final rooms of museum presentations of power generation and spaces for interactive learning for kids. The Gallery, however, offers another kind of interactive experience, for kids and adults alike, the work offering a contemplative, meditative, somewhat-heavenly glow as people mediate around it trying to work it – and perhaps themselves – out. Originally made for Tate Britain’s Duveen Commission, filling its neoclassical hall in 2017, here it seems to find a spiritual home.

Energy in Wyn Evans’ works is more than what comes from the sockets. It emits light and warmth, sure, but also carries references to art history, musical notation, theatrical choreography, architectural sketching, celestial imaginings, and experimental physics. More, it carries what the reader places into it. As both a presence and void, as something that seems immediate and distant, it feels like a sculptural work that can hold an immense amount of personal meaning despite its looseness of form.

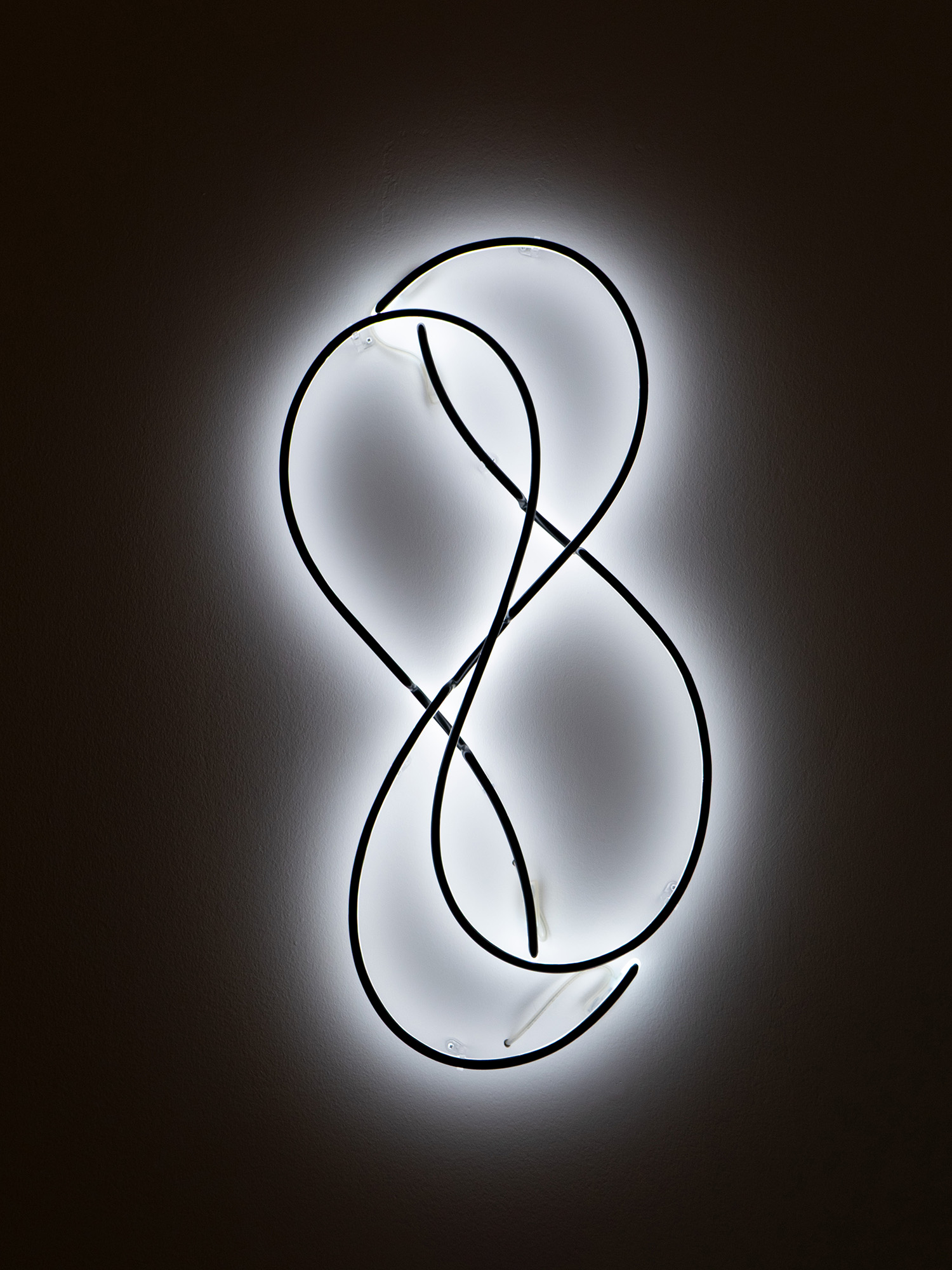

The wider exhibition comprises several other Wyn Evans works, all dealing with the artist’s preoccupations with light, communication of energy, presence, poetics, and experience. None of the scale or impact of the poster-child of the show from the main void, but all offer their own unique mode of subtlety and shifting. This is not an exhibition formed of iconic moments, but of delicate shifts and gestural impression. Indeed, in the somewhat compressed and impersonal gallery spaces away from the main hall, the qualities of some of the works are lost.

![]()

![]()

Rows of white neon grids, Neon after Stella I-VIII(2022) fills a secondary space. There is reference here to the modernist abstraction of the artist namechecked in the title, Frank Stella, transforming his dark canvas into bright light. Overlapping, they create an unreliable space of sliding surfaces and flickering moiré – nobody walks quickly around these works, scale and distance become less important experientially, the mind and body needing to re-configure and re-coordinate to a new way of being around things.

Other works seem even more precarious for the navigating visitor. Composition in Panes (on Reflection) (2017) is formed of hanging panels of low-iron glass 6-channel audio. Arranged as if to invite the visitor to get close, where they not only hear a soundwork softly reverberating from the glass but also feel an intense nervousness from the fragility.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Standing sculptures formed of random found material, sound equipment are a kind of gesamtkunstwerk-gone-wrong assemblage that at first appear far from delicate nature of the glass and light works, but with time also reveal a delicate precarity. TIX3 (1994) is a circular hole in the ceiling filled with the green glow of a reversed EXIT sign – another sense of the ecclesiastical, messages that go both skywards and eathwards, inviting transfiguration and personal journey, creating anxiety within the architecture.

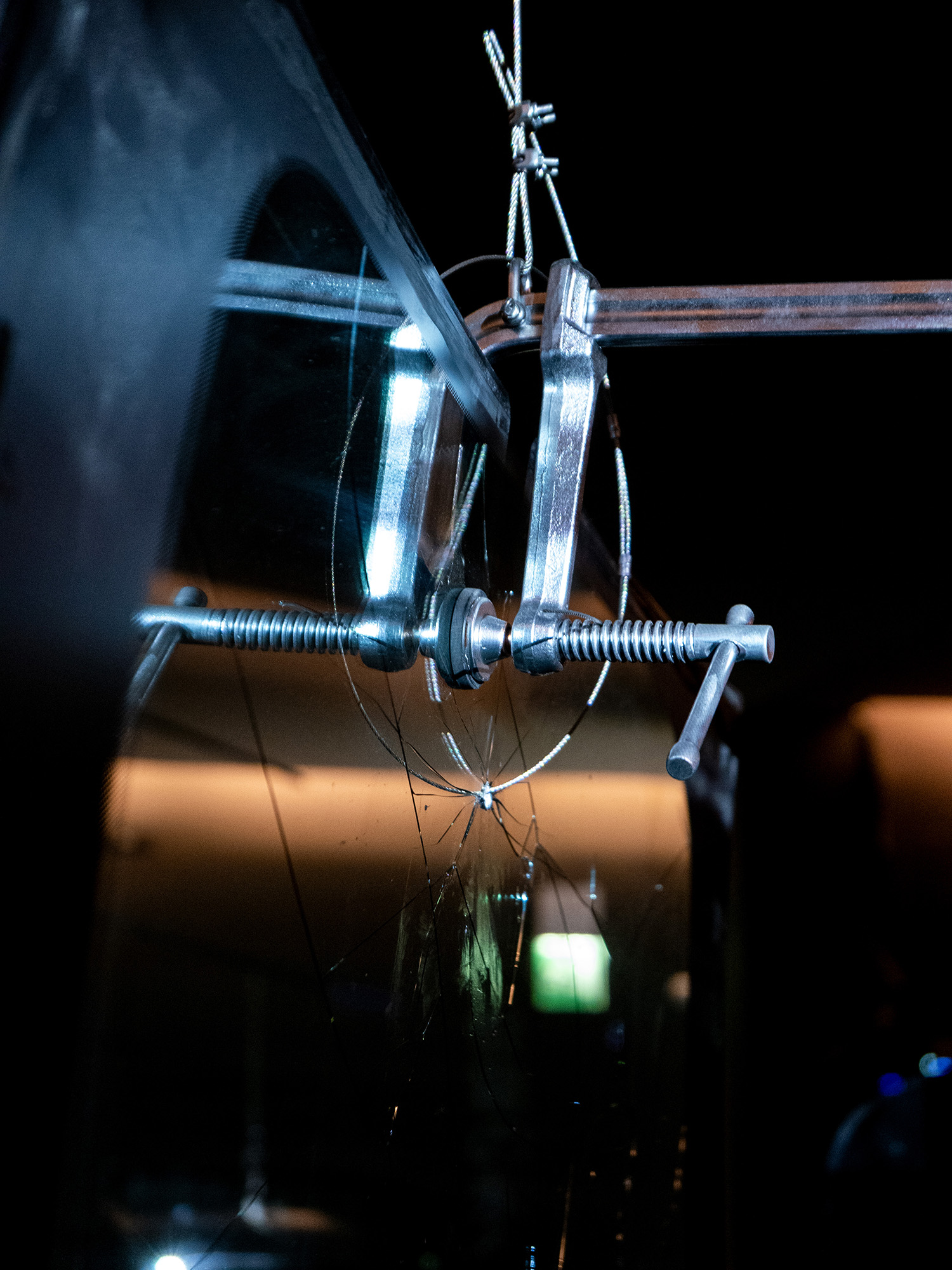

The final room offers an immensity of experience as the opening hall does, but far more intimate. Phase Shift I-II-III with projections (after David Tudor) for maat (2025) is a new work named after the American experimental pianist and composer, Wyn Evans’ work acting as a kind of intense industrial operetta. Tudor designed several phase shifting devices to bend the phase of signals, bending harmonics to push against predictable processes of digital sound. Wyn Evans has made a series of his phase shift sculptures, this version comprising three of the works in a compact, dark space.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Formed of hanging smashed car windscreens hung Calder-like from the ceiling, usually the works are presented in bright, white spaces. Here, in the darkness, shot through with projection and lights, the cracked glass transforms into a post-industrial shadow puppetry. Gently rotating in the space and lights, impacted by both chance of movement and poetic interaction with Tudor’s music – sometimes soothing, sometimes harsh – the experience is exhilarating, as if time has entered a Ballardian slo-mo motorway crash, where amongst flying windscreens and musical notes there is the briefest moment of calm.

There is energy throughout Cerith Wyn Evans – Forms in Space… by Light (in Time) at MAAT, some through the sockets and some through an intimacy of experience. Lights throb, fragility floats, works carry a nervousness yet are solidly present. It is work that speaks to both the modern order of energy production, systemic logic, and artworld objectness yet flickers with spirituality, existential curiosity, and anxiety. These are not easy things to carry in contemporary art, with all its baggage of value, market, and structure. Here, it glows.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Sometimes, artists or exhibitions seem perfectly paired for a space, and the meaning of both art objects on display and the surrounding architecture marries. This often happens within an historic or classical setting, where messages of new works juxtapose or mingle with an historic narrative, but at MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology alongside the River Tigus outside the centre of Lisbon a thoroughly contemporary space makes the perfect setting for a solo exhibition by Welsh artist Cerith Wyn Evans.

Wyn Evans’ most well-known works entangle neon, electricity, and light into sculptural forms that flicker and shimmer bright whiteness. The host venue, MAAT, is owned and operated by EDP, a Portuguese electrical utilities company, and is formed of two impressive pieces of architecture: the red brick 1908 Tejo Power Station and adjoining Gallery building designed by Amanda Levete, founder of London-based AL_A architecture studio, within which Wyn Evans’ works throb.

Externally, Levete’s MAAT Gallery building, now a decade old, is already a foundational part of Lisbon’s cultural and touristic boom. White ceramic surfaces seem to peel from ground level to reveal entrances and openings which let both people and natural light into the entombed gallery spaces. The void between overhang and riverside promenade has become one of the city’s most Instagrammable moments, while the roof offers visual access to a wide vista and a bridge across railway lines to the residential parts of Belém.

Inside, the architecture is dominated by a central void, a parametricised Guggenheim ramp with a gentle Baroque curve wrapping around the main central gallery space. Other, less successful (from a visitor and curatorial standpoint) lead off this central void, but the visitor sequence that folds from outside to inside to curled entombing void is one that few international museums can rival.

It also makes a perfect ready-made setting for Wyn Evans’ Forms in Space… by Light (in Time) (2017), an enormous entanglement of pure white light seemingly stuck in mid-explosion, comprising nearly 2km of neon. Upon entry it is arresting, and invites pause as if to capture scale, complexity, and even logistics. But as soon as some sense of it has been gained, and the visitor moves onwards along the curved ramp, it immediately transforms. Almost impossible to read, any movement around or under its interlocking arrangements completely changes its form, swooshes and lines that seemed conjoined quickly separate to show themselves as distant relatives, moments of perfect geometry twist away to reveal as sinuous, unexpected lines.

That it is entirely constructed of electricity is present not only in the soft flicker and gentle hum of transformers, but also in the fact that the building itself is so rooted in the heritage of power. The former power station next door is now a labyrinth of heritage industrial assets which emerge into final rooms of museum presentations of power generation and spaces for interactive learning for kids. The Gallery, however, offers another kind of interactive experience, for kids and adults alike, the work offering a contemplative, meditative, somewhat-heavenly glow as people mediate around it trying to work it – and perhaps themselves – out. Originally made for Tate Britain’s Duveen Commission, filling its neoclassical hall in 2017, here it seems to find a spiritual home.

Energy in Wyn Evans’ works is more than what comes from the sockets. It emits light and warmth, sure, but also carries references to art history, musical notation, theatrical choreography, architectural sketching, celestial imaginings, and experimental physics. More, it carries what the reader places into it. As both a presence and void, as something that seems immediate and distant, it feels like a sculptural work that can hold an immense amount of personal meaning despite its looseness of form.

The wider exhibition comprises several other Wyn Evans works, all dealing with the artist’s preoccupations with light, communication of energy, presence, poetics, and experience. None of the scale or impact of the poster-child of the show from the main void, but all offer their own unique mode of subtlety and shifting. This is not an exhibition formed of iconic moments, but of delicate shifts and gestural impression. Indeed, in the somewhat compressed and impersonal gallery spaces away from the main hall, the qualities of some of the works are lost.

Rows of white neon grids, Neon after Stella I-VIII(2022) fills a secondary space. There is reference here to the modernist abstraction of the artist namechecked in the title, Frank Stella, transforming his dark canvas into bright light. Overlapping, they create an unreliable space of sliding surfaces and flickering moiré – nobody walks quickly around these works, scale and distance become less important experientially, the mind and body needing to re-configure and re-coordinate to a new way of being around things.

Other works seem even more precarious for the navigating visitor. Composition in Panes (on Reflection) (2017) is formed of hanging panels of low-iron glass 6-channel audio. Arranged as if to invite the visitor to get close, where they not only hear a soundwork softly reverberating from the glass but also feel an intense nervousness from the fragility.

Standing sculptures formed of random found material, sound equipment are a kind of gesamtkunstwerk-gone-wrong assemblage that at first appear far from delicate nature of the glass and light works, but with time also reveal a delicate precarity. TIX3 (1994) is a circular hole in the ceiling filled with the green glow of a reversed EXIT sign – another sense of the ecclesiastical, messages that go both skywards and eathwards, inviting transfiguration and personal journey, creating anxiety within the architecture.

The final room offers an immensity of experience as the opening hall does, but far more intimate. Phase Shift I-II-III with projections (after David Tudor) for maat (2025) is a new work named after the American experimental pianist and composer, Wyn Evans’ work acting as a kind of intense industrial operetta. Tudor designed several phase shifting devices to bend the phase of signals, bending harmonics to push against predictable processes of digital sound. Wyn Evans has made a series of his phase shift sculptures, this version comprising three of the works in a compact, dark space.

Formed of hanging smashed car windscreens hung Calder-like from the ceiling, usually the works are presented in bright, white spaces. Here, in the darkness, shot through with projection and lights, the cracked glass transforms into a post-industrial shadow puppetry. Gently rotating in the space and lights, impacted by both chance of movement and poetic interaction with Tudor’s music – sometimes soothing, sometimes harsh – the experience is exhilarating, as if time has entered a Ballardian slo-mo motorway crash, where amongst flying windscreens and musical notes there is the briefest moment of calm.

There is energy throughout Cerith Wyn Evans – Forms in Space… by Light (in Time) at MAAT, some through the sockets and some through an intimacy of experience. Lights throb, fragility floats, works carry a nervousness yet are solidly present. It is work that speaks to both the modern order of energy production, systemic logic, and artworld objectness yet flickers with spirituality, existential curiosity, and anxiety. These are not easy things to carry in contemporary art, with all its baggage of value, market, and structure. Here, it glows.

Cerith Wyn Evans (1958, Llanelli, Wales) is renowned for his

diverse artistic practices, including sculpture, installation, photography,

film, and text, and his unique approach to art, often exploring themes of

language, perception, and temporality. After studying at Saint Martin's School

of Art and the Royal College of Art in London, Evans collaborated with Derek

Jarman, a significant influence on his career. His early works employed film

and video, but his use of neon lights and text-based works, which often

incorporate literary references and philosophical texts, creating immersive and

thought-provoking experiences for viewers, turned out to be the most recurring

throughout his production.

In 2003, Cerith Wyn Evans represented Wales at the country’s

inaugural pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale, where he also participated in

1995 and 2017. His artistic career is punctuated by the participation in major international

exhibitions like the Documenta 11, Kassel (2002), and Istanbul Biennial (2005),

Yokohama Triennale (2008), Skulptur Projekte Münster (2017), and the Liverpool

Biennial (2021), and solo exhibitions at prominent institutions such as Tate

Britain, London (2010), Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (2006), and

the Serpentine Gallery, London (2014). More recent exhibitions include his solo

show at Museo Tamayo, Mexico City (2018), Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan (2019), Aspen

Art Museum (2021), Sogetsu Kaikan, Japan (2023), Centre Pompidou-Metz (2024),

and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney (2025).

Cerith Wyn Evans' works are held in several prestigious

collections, including the Tate Collection, London; the Museum of Modern Art

(MoMA), New York; the Fondation Louis Vuitton; the Centre Pompidou, Paris; and

the Guggenheim Museum, New York.

MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology opened

in October 2016 in the context of the EDP Foundation's longstanding cultural

patronage policy as an international institution dedicated to promoting critical

discourse and creative practice in order to foster new understandings of the

historical present and a responsible commitment to our common future.

Located on the waterfront in the historic area of Belém in

Lisbon, the EDP Foundation campus covers an area of 38,000 square metres that encompasses

a reconverted thermoelectric power station - the Tejo Power Station, an

emblematic building of industrial architecture built in 1908, and a new

building designed by the London architecture studio AL_A (Amanda Levete

Architects). Both host exhibitions and events programmed by MAAT and are linked

by a garden designed by Lebanese landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic.

www.maat.pt/en

Will Jennings is a London based writer, visual artist & educator interested in cities, architecture & culture. He has written for Wallpaper*, Canvas, The Architect’s Newspaper, RIBA Journal, Icon, Art Monthly & more. He teaches history & theory at UCL Bartlett & is director of UK cultural charity Hypha Studios.

www.willjennings.info

Located on the waterfront in the historic area of Belém in Lisbon, the EDP Foundation campus covers an area of 38,000 square metres that encompasses a reconverted thermoelectric power station - the Tejo Power Station, an emblematic building of industrial architecture built in 1908, and a new building designed by the London architecture studio AL_A (Amanda Levete Architects). Both host exhibitions and events programmed by MAAT and are linked by a garden designed by Lebanese landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic.

www.maat.pt/en